|

THERE is little doubt that in the minds of

most people the name of Paul Jones instantly calls up the form of a

villainous pirate seeking whom he could devour. Varied as was his

career, the Skull and Crossbones never fluttered from his mast-head; he

never commanded privateer or smuggler, or sailed with even a letter of

marque. From the day he left the merchant service, with the exception of

two years on his plantation, he was in the navy of the United States,

and later in the service of Imperial Russia, though still holding his

former commission. But a century ago the word America, to the world at

large, invoked a vague jumble of Indians scalping captives at the stake,

bloodthirsty buccaneers, and all sorts of joyful lawlessness in which

Morgan, Captain Kidd and John Smith, with Pocahontas in the background,

rollicked shoulder to shoulder in the jollity of universal brotherhood.

By a process of reasoning the colonists became desperate law-breakers,

and Paul Jones, from the fact of such association with ships and

colonists, developed into the dare-devil pirate of fiction, with red

shirt carelessly flung open, displaying a brawny chest, luridly tattooed

with fearful and mystic symbols. An individual with slouched hat pulled

low over his villainous countenance, who in place of the necessary and

harmless cigarette, carried between his clenched teeth a gleaming

cutlass, oblivious of the discomfort of such a pastime, when he wished

to rush hastily through a narrow hatchway. His sash bristled with

pistols, which he habitually used in target practice on his crew or to

stimulate the exertions of such of his passengers as were occupied in

the gymnastic and risky exercise of walking the plank. The name of the

"Black Douglas" was not more terrifying in his day than that of Paul

Jones; in fact, it is quite unbelievable if there were not authentic

records of the fact. Many a merchant would have rejoiced to hear that he

had died the customary hanging-in-chains death of the pirate he never

was, for, had not his desperate forays on unprotected coasts and in home

waters doubled the rate of insurance.

Paul Jones was the theme of endless ballads,

chapbooks and prints, embodying in his person as he did, without

recourse to the inventiveness of the writer, all the romance needed to

weave a glowing tale. His personality was fascinating, as was the hint

of mystery and noble birth clinging to him; he enjoyed a noted success

in the world of fashion, and became the intimate of royalties; his

unsurpassed brilliancy as a commander, his conquests in love and war

created a character which for a typical hero could not have been outdone

by the most fertile pen.

From the date of his death, 1792, until

the early part of the eighteenth century, he was the subject of many a

tale, whose inventors let nothing stand in the way of embellishment. He

is generally described as the "son of the Earl of Selkirk's head

gardener, but his real father is Captain John Maxwell, Governor of the

Bahama Islands." In others, he was left on the doorstep of the Paul

cottage, to be brought up as one of their children. Some time in his

early infancy he became a desperate smuggler, rapidly saved up two

hundred pounds, and in his varied enterprises got to the north coasts,

where exciting adventures came thick and fast.

"Being impressed on a man-o'-war, he

availed himself of the first opportunity to escape, and the second time

commenced a smuggler, and assumed the command of a vessel himself,

appointing such of his companions officers as he knew from experience to

be able seamen. The crew consisted of sixteen persons, and the vessel

was provided with every kind of ammunition and necessary for hazarding

desperate adventures, and proved a most formidable annoyance to the

maritime trade of the whole kingdom."

No sooner had war broken out between

England and America than he rushed off to the latter country, entering

into negotiations with "Silas Deane and others," to whom he offered

"very valuable communications and intelligence. He obtained from time to

time several remittances," which enabled him to "cross the Atlantic to

Europe twice, to pick up further particulars of our coasts. Upon this

account he is generally said to have changed his name, and assumed that

of Captain Paul Jones. Government not being apprised of the sort of spy

that had arrived in the country, he was at liberty to go about the

capital, and dwelt f or a short time at Wapping," where, according to

this narrative, he occupied himself in buying up all the maps, charts,

soundings and information having to do with the coasts that he could get

his hands on, "all this information making him more valuable to those

who employed him." He goes through stirring scenes in the early part of

the revolution, and, one is inclined to wonder if there is more truth

than fiction in the comments the writer makes on the fiasco with the

Glasgow, alleging that the "Commander of the Fleet Ezekiel Hopkins was

in reality in the pay of the enemies of his country."

Paul is credited with a number of voyages

that would have put the Ancient Mariner to the blush, and taken several

lifetimes to make. His failure to take the Drake the first time is laid

to the fact that "the mate, who had drunk too much brandy, did not let

go the anchor according to orders," and this is amusing, for the

official report lays the blame on the mate, though the brandy is not

mentioned.

The description of his informal call at

St. Mary's Isle is not to be omitted, as, after some preliminary

conversation, "Lady Selkirk herself observed to the officers that she

was exceedingly sensible of their commander's moderation; she even

intimated a wish to repair to the shore, although a mile distant from

her residence, in order to invite him to dinner; but the officers would

not allow her ladyship to take so much trouble." Such a charming entente

cordiale between a peeress of the realm and a piratical son of the sea

in the midst of war is quite idyllic, and it is no wonder Paul spared no

expense in returning the family plate at the earliest opportunity.

Paul had an eye for stage effect, such as

dressing his men up in "red clothes," and putting some of them aboard

the prizes to give the appearance of transports full of troops. The

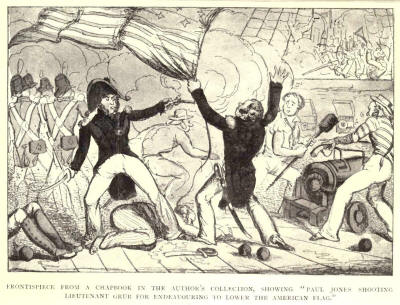

action between the J3onlzornme Richard and the Serapis is thrillingly

described, being illustrated by a lurid picture of "Paul Jones Shooting

Lieutenant Grub For Endeavouring to Lower the American Flag to the

Serapis, Captain Pearson, off Flamborough Head, Sept. 1779." In this

memorable scene Paul is adorned with a pair of jet-black whiskers, of

the " Piccadilly weeper" fashion, that would have wrought havoc with the

heart of an Early Victorian beauty. Considering the heated and

sanguinary engagement in which all parties were participating, the

exquisite neatness of the Commander's white trousers is most noticeable.

To continue this exciting tale, the

captain of the Serapis, "hearing the gunner express his wish to

surrender in consequence of his supposing that they were sinking,

instantly addressed himself to Jones, and exclaimed, 'Do you ask for

quarter? do you ask for quarter?' Paul was so occupied at this period,

in serving three pieces of cannon on the forecastle, that he remained

totally ignorant of what had occurred on deck. He replied, however, 'I

do not dream of surrendering, but I am determined to make you strike!'

In this dilemma, Lieutenant Grub proceeded directly to tear the stripes

from the stump they had been nailed to. The Commodore caught him in this

disgraceful act, and shot him instantly with a boarding-pistol, which,

as it is a circumstance of remarkable temerity, has as often been

asserted as denied, and not seldom misrepresented; but the reader is

assured of the fact, which came from the most undoubted authority, that

of Lieut. Wm. Grub's widow.'"

Alas, for the veracity of "Wm. Grub's

widow"! The roster of the f3onlzomme Richard shows but one of that name,

and he, "Beaumont Grub, midshipman," was "absent and not in action." And

in the ship's log there is no mention of Jones having shot any one.

As many famous actors used to play

classical parts in contemporary periwigs and red-heeled shoes, copying

the exaggerated dress of the fops who patronised them, so fashion has

left its stamp on the mass of prints handed down to us. Pictures of Paul

Jones vary as much as the histories of him, and even in the portraits by

recognised artists, his eyes rival the chameleon, sometimes black, at

others an innocuous bluish-purple, as in the miniature at the Hermitage,

St. Petersburg; while that painted by the Comtesse de la Vandhal, which

was his favourite portrait, gives him eyes of a dark but elusive hazel.

In a print of the Grub incident, issued in 1826, Paul and the

nonexistent Grub are depicted with resplendent ebony whiskers, while in

an earlier one, about 1803, when these adornments were not fashionable,

they are guileless of such attractions, though Paul is shown with a

beautiful nose, strongly reminiscent of the Iron Duke. He also wears

top-boots, and Mr. Grub is stylishly clothed in striped trousers, which

add a certain éclat to the scene of battle. The Comtesse de la Vandhal's

miniature presents him as a man of fashion in all the nicety of Court

dress, but above all, Houdon's bust is the most characteristic,

reproducing the keen, shrewd, strong features, the forceful

concentration, the virility of purpose and doggedness, without which he

could never have succeeded. The artist's conception of him is as varied

as the historian's idea of his character. From a low-browed, snub-nosed,

villainous individual, with a negligee shirt and sash full of pistols,

to one wherein he resembles "the Father of his Country," if that

gentleman ever appeared minus his wig in the stress of battle, they run

the gamut. He had remarkably well-shaped hands, as, in the three-quarter

portraits of him, this fact is generally emphasised, unless, after the

fashion of Sir Joshua Reynolds, one pair of elegant hands served the

artist of his day as models for every sitter.

As is the case with a man who had such

ardent admirers, Paul had his detractors, bitter and unscrupulous,

unsparing in their malignant slanders. He is supposed, after having

completed his "servitude" with Captain Johnson, to have "signed articles

with Captain Baines, who was then in the Guinea trade; and here his

cruel disposition blazed forth in its proper colours by his attempt to

sink and destroy the ship and cargo, in consequence of a slight

reprimand from the captain, who was a man that bore an excellent

character for justice and humanity to his inferiors. For this offence he

was brought home in irons; but owing to some defect in the evidence

produced on his trial, he was acquitted of the charge." After admitting

that this voyage changed Paul's views of a seafaring life, and made him

stay ashore, the writer naively remarks: "We are sorry to observe that

in this part of the history we have no favourable record to make of the

wanderings of our turbulent hero."

Though every moment of these years is now

accounted for, this anonymous writer, more remarkable for his total

abstention from the truth than anything else, endows young Paul with

characteristics that would put the rakes of the Restoration to the

blush.

"After committing a number of excesses in

the neighbourhood of his patron's residence the patron being Lord

Selkirk, who, it is an authentic fact, Paul Jones had never seen, though

his father is assigned to him as gardener, and his services with Mr.

Craik ignored—" he attempted to seduce (and but too successfully

succeeded) the virtue of some three young women of some respectability;

two of whom soon after became pregnant. The evil did not stop here; it

appears he was resolved upon completing the wretchedness of his victims,

and placing his own villainy beyond the possibility of a doubt. For it

was no sooner known by Paul that the young persons were in a thriving

way, than he endeavoured, by his artifices and insinuations, to prevail

upon each of them to form an acquaintance with a wealthy farmer, for the

sole purpose of making him father the unfortunate and innocent

offspring! And it is a fact generally accredited, that he completely

succeeded in this abominable design."

Not satisfied with this scandal, it

continues, " From the respect the Earl of Selkirk had for his father,

young Paul was admitted into the house as a domestic, but not without

some excellent admonitions from his father, who earnestly entreated him

to leave the dissolute part of his companions and take himself seriously

to amend his life. In this, as in many other cases, it proved only loss

of time to reason with so depraved a character, for he had no sooner got

into this situation, than he paid his addresses to one of the females in

the house, and who very prudently refused to accept them. But Paul had

made sure of this prize also, and determined to run all hazards rather

than forgo the objects of his pursuits. He accordingly watched an

opportunity when he saw her enter the dairy, and immediately rushed in

and fastened the door after him, he then, in the most deliberate manner

proceeded to insult the terrified woman, and had nearly accomplished her

ruin, when her repeated shrieks brought the Earl (who was at that time

near the spot) "—evidently being an inquisitive peer with an interest in

dairy farming—"to her assistance. So flagrant an act of injustice could

not easily be forgotten, and in lofty language the Earl banished such a

desperate character from his estates," this reason being very

ingeniously made the motive for the attempt to carry off Selkirk some

years later.

And the reader will learn, " Paul's

hatred to the Earl, from this occurrence, was continually rankling in

his bosom; and that he embraced the first opportunity for retaliating."

Not satisfied yet, Paul became a

smuggler, and married a "beautiful farmer's daughter with three hundred

pounds." But life ashore becoming monotonous, he again headed his

smuggler's hand, running into "a port in France, and after most

tempestuous weather (during which Paul actually threw a man overboard

for a trifling disobedience of orders!) arrived at Boulogne, where the

cargo was disposed of, to a great disadvantage from the damage it

sustained in the last storm."

If Paul had lived a few years later he

would have been one of the shining lights among the "Latter Day Saints,"

for "our hero now turned his thoughts towards a smirking widow "—not

having had the benefit of the immortal Mr. Weller's advice—" the

mistress of the hotel where he too had lodgings during his stay in

Boulogne." But this "merry widow" was well able to take care of herself,

and "after using every kind of stratagem for three months successively

without being able to prevail upon the fair hostess to accompany him to

the altar of Hymen, he deposited two hundred guineas as a proof of the

sincerity of his intention to return and render her completely happy,

and then took an affectionate leave." Once on the seas he reverted to

the joys of a smuggler's life. "Rightfully judging that Dover was an

eligible situation, he hired a capital house there, and figured as a

first-rate merchant. Having a confidential superintendent, he had many

opportunities of visiting the whole coast; and in one of his excursions,

falling in with a number of associates, they formed the resolution of

boarding an armed vessel in the Downs, which had been fitted out by our

merchants to act against the Barbary cruisers. Enterprising and

audacious as this undertaking was, from the numerous revenue cutters

usually stationed in the Downs, they completely succeeded; two men and a

boy were the only persons on board, and from their never having been

heard of, the owners supposed the vessel had been driven out to sea, and

that all on board perished."

Then Paul goes through a variety of

stirring events, vanquishing customs-house men, after sanguinary fights,

landing under the cover of dense fogs, and plundering houses of gold and

jewels, to which the famed riches of Golconda were "as moonlight unto

sunlight." From Sussex to the Isle of Man they roved, ultimately

receiving intelligence of some merchant ships laden with gold and

silver, which they took, "and that not one of the richest; but Paul

Jones, finding himself entitled to a share amounting to upwards of five

hundred pounds, determined to pursue his amour at Boulogne."

Where, during all this time, was his

legal bride, "the beautiful farmer's 'daughter," who does not appear

again in the narrative? On reaching l'Orient, Paul generously presented

"the vessel and her appurtenances" to his companions; binding them,

however, in a solemn oath that they should deal with him only in such

articles as were proper for sale at Boulogne and the Isle of Man. . . .

Paul slept that night ashore; and in the morning, after sending his

comrades a present of twelve dozen of wine and a liberal supply of fresh

provisions, set out for Boulogne. On his arrival he was heartily

welcomed by the widow, with whom he had held correspondence during the

several months of his absence." Bigamy had no terrors for this

roistering blade, as "in about five days they were married, and having

assumed the character of landlord, he gave the principal customers of

the house an elegant entertainment. For several weeks his behaviour was

so affable and condescending, and the articles in which he dealt so good

of their respective kinds, and so moderate in price, that the custom of

the house surprisingly increased. But nature had not made him to keep

within the bounds of moderation. The idea of being possessed of property

sufficient to render him independent of business, and the prospects of

greater riches, swelled his pride to that pitch that he was no longer

able to act under the mask of humility that had for some time disguised

his natural turbulence." Just what he did is not hinted, "but the

customers were disgusted with his shameful conduct . . . and sought

other places of entertainment," so possibly Paul raised the prices. "The

decay of the business inflamed him to a degree of the utmost

extravagance; and in all probability his wife would have fallen a

sacrifice to the impetuosity of his temper had not the amiable'

tenderness of her disposition been capable of giving some degree of

moderation to his violent, restless and impatient spirit."

Apparently he had a partiality for

smuggling transactions connected with the Isle of Man, and hearing that

the Earl of Derby was about to sell it to the Crown, he decided to "go

there and put his affairs on a firm footing, which he did, leaving his

wife in charge of the hotel. . . . On the high seas he met his old

pirate crew, but waved his hand in token of greeting," upon which they

sailed away leaving him unmolested. "As soon as he arrived he made the

first entry of licensed goods transported from England into the Isle of

Man." Returning to Boulogne he carried on his smuggling until the death

of his wife, when he "again went to the Isle of Man, and transacted some

business in the legal way the better to elude the suspicion of his being

engaged in contraband dealing," though, sad to relate, except with the

law, smugglers were exceptionally popular characters, helped by high and

low alike in their efforts to foil the "Preventive" men.

If he ever went to see bride the first,

there is no note of the fact; undoubtedly he did not, being a very much

occupied individual with his many sporting ventures, not "yet an

absolute pirate, but a desperate smuggler." His crew was formed of

ruffians of all nationalities, "Blacks, Swedes, Americans, Irish and

Liverpool men were particularly welcome to him, and in the north of

England he was called the English corsair." He amassed three thousand

pounds in these ventures, but his "avaricious mind had led him to take

great advantage of several of the smugglers with whom he dealt, some of

whom he apprehended might at length be provoked to lodge information

against him on account of the illegal traffic he had so long pursued."

So he got rid of his various encumbrances, and went to keep a

coffee-house in Dunkirk—stocked with the money which he had borrowed

from confiding individuals before leaving the Isle of Man. He kept on

dealing in contraband goods, but was "driven nearly to a state of

distraction by those to whom he had entrusted his goods allowing them to

be seized, as through his want of precaution the goods had fallen into

the hands of the king's officers." Paul now shut up his house in

Dunkirk, and prepared to embark for England, having "previously remitted

a small sum to each of the persons he had defrauded in the Isle of Man;

and as they accepted of payment in part, they destroyed every idea of

felony, and constituted their respective claims into mere matters of

debt; he was therefore no longer under apprehension of prosecution from

the criminal laws."

Having concluded the matters which

brought him to Rochester, Paul re-turned his attention to the ladies.

Taking a "lodging in Long Acre, where he had not resided many weeks

before he debauched his landlady's daughter, who removed with him to

Tottenham, but in about three weeks he deserted her, and she became a

common prostitute." Shocking to relate, "Our hero now engaged in a

criminal intercourse with the mistress of a notorious brothel in the

neighbourhood of Covent Garden, who assumed his name, and passed under

the character of his wife." But again was he bereaved, "the woman being

seized with a fit of apoplexy, she expired while he was examining some

accounts in a parlour adjoining to her bedroom. He no sooner discovered

her situation, than he searched her pockets, and taking her keys,

secreted all her ready money, and some other valuable effects, amounting

in the whole to about three hundred pounds, and then absconded with his

booty." Moving to Paternoster Row, where he gambled recklessly, until

reduced to the sum of £io8, with which, after a good deal of brawling in

billiard-rooms and pot- houses, he again went to sea as a smuggler,

"committing many depredations along the coast, and capturing a Spanish

galleon of inestimable treasure, which struck on a rock, going to the

bottom with all hands on board. There were innumerable merchant vessels

that found him unpleasantly on the alert, and on one foray he went to

Whitehaven, where he seized a young woman while she was standing on the

wharf, and placed her in the hold; and the following day he enticed a

publican on board, and immediately got under weigh. The man returned

several years after, but the woman has never been heard of since."

Now all this is an amazing tissue of

lies, as Paul Jones was born in 1757 and went to America in 1773, he was

less than seventeen when most of these disreputable adventures were

being enacted. Is it odd that he was spoken of with bated breath,

shunned as more dangerous than the plague, and that mothers hushed

naughty children with the invocation of his name? His services in France

and Russia are ignored, and he is sent to Kentucky, where he gained

great wealth and estates, dying in the early eighteen hundreds.

In a three-volume romance by Allan

Cunningham, Paul dies in Paris, poor and miserable, wrapped in his cloak

on a truckle bed, just as he is about to receive the appointment of

commander of the Republican navy; Fenimore Cooper wrote of him in Tue

Pilot.,- and Thackeray in Dennis Duval, and Dibden wrote a "melodramatic

romance" about him, which was played at the Metropolitan minor theatres,

and the great Dumas took him as the subject of one of his least-known

novels, under the title of Captain Paul. In this book he is the natural

son of a great French family, a beneficent dens ex maclzina to his left-

handed brothers and sister, whom he showers with favours. On the many

voyages which he made to the West Indies, he always visited this sister

and her husband, who was governor of Guadeloupe. The story floats in

hysterical tears, in which Paul joins frequently, finally disappearing,

after a touching scene with his mother, who presses on his acceptance a

diamond-encrusted miniature of his long dead father, the Comte de

Morlaix. This, for twenty-five years, the secretive lady had kept,

unknown to her husband, who shot Paul's father in a duel, where the

latter refused to fire; an incident so disturbing to his mind that he

went mad. It is a great jumble, with all the elements of purest

melodrama. That very puissant lady, Margaret Blanche de Sable, Marquise

d'Auray, his mother, was an austere character with a great reputation

for piety, and her children stood in wholesome awe of her. She must be

pardoned her early indiscretion, for she had been engaged to the Comte

de Morlaix, when, alack! a sort of Montagu-Capulet unpleasantness

happened, and the lovers were parted. Dumas, with most unusual

inaccuracy, buries his hero in Père la Chaise, which was not opened

until 1804.

The ballad writers sang in praise of his

deeds, quite unfettered by hampering truth, and the following is one of

the best examples. It begins—

PAUL JONES

(From the collection of A. M. Broadley, Esq.)

"An American frigate,

called the Rachel by name,

Mounted guns forty-four, from New York she came,

To cruise in the Channel of old England's fame,

With a noble commander, Paul Jones was his name.

We had not cruised long when two sails we espied,

A large forty-four, and a twenty likewise.

Fifty bright shipping, well loaded with store,

And the convoy stood in for the old Yorkshire shore."

It goes on to relate how they came

alongside, with the customary interview through the speaking-trumpet,

and says—

"We fought them four

glasses, four glasses so hot,

Till forty hold seamen lay dead on the spot,

And fifty-five more lay bleeding in gore,

While the thun'dring large cannons of Paul Jones did roar."

The fight continued amid much smoke of

battle, and

"Paul Jones he then

smiled, and to his men did say,

Let every man stand the best of his play,'

For broadside for broadside they fought on the main

Like true buckskin heroes, we returned it again.

The Cerapus wore round our

ship for to rake,

Which made the proud hearts of the English to ache,

The shot flew so hot we could not stand it long,

Till the bold British colours from the English came down.

And now, my bold boys, we

have taken a rich prize,

A large forty-four, and a twenty likewise;

To help the poor mothers, that have reason to weep,

For the loss of their sons in the unfathomed deep." |