|

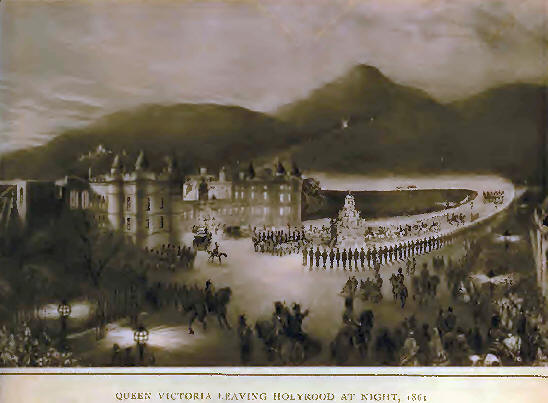

EDINBURGH was connected, and

that in a most painful way, with the death of the Prince Consort at the

close of the year 1861. Two great works in Edinburgh were inaugurated

shortly before by the laying of the foundation stones, first of the New Post

Office and then of the Royal Museum, both of which ceremonies were performed

by the Prince on the same day. I was on duty in command of my rifle

battalion on that day as we lined the way from the site of the Post Office

in the direction of Holyrood. I little thought It was to be the last

occasion on which I should see the Prince Consort, as he looked the picture

of health. But it is to be feared that it cannot be said that this visit had

nothing to do with his death, which occurred but a short time afterwards.

The weather of that day was dreadful, the sky dull as lead, and the east

wind more than usually penetrating, seeming to reach one's very bones. I

confess that in my position as a commander of a battalion, I made use during

the long period of waiting of my privilege of looking after my command, by

every now and again having a gallop to the outmost flank of my line and

back, ostensibly to look after things, but more to bump the cold out of my

body. The ceremony took a long time, and we learned afterwards that there

had been a very long prayer—i injudiciously long, both for the occasion and

also in view of the weather, to which full dress tunics could offer little

resistance. Twenty-five minutes was declared to have been the time occupied,

but this is almost beyond belief. Whatever the time was it was too long, and

to be regretted to say the least of: . The Prince was urged to put on his

cocked hat, but this he would not do, expecting every minute, it may be

supposed, that he would be able to do so without appearing irreverent. So

his bald head was exposed all the time, and doubtless the cold was

penetrating his clothing as well. Had this been the only ceremonial, he

might have got back to the Palace and obtained relief. Most unfortunately he

had to drive a good part of a mile, and perform a similar ceremony at the

site of the new Museum. But a short time after this I saw the Castle flag at

half-mast high on a Sunday forenoon. It may be probable that the seeds of

the end which led to this national calamity had been already sown, but it s

difficult not to harbour the thought that, but for the lamentable exposure

he had to endure, his fine healthy constitution might have shaken off the

disease. He was mourned with genuine grief by all who admire a servant

devoted to good, and who realised what a true helpmate he was to the Queen

in bearing the burden of royalty.

As was natural, Edinburgh

resolved to have a memorial of the Prince, and this led to proposals, some

of which it was scarcely possible to think that any sane person would put

forward. Comment has been made on the disfigurements that have been

inflicted upon Edinburgh, one especial —Nelson's Monument—of which Lord

Cockburn said, writing to the Lord Provost: "If your lordship wishes to see

how a coign of vantage may be made use of for prominent deformity, raise

your eyes to Nelson's Monument." Augustus. I C. Hare speaks of it as "a kind

of lighthouse which closes Princes Street." Perhaps in connection with the

sad death of the Prince Consort a few words may be said on what the citizens

have been spared from having to endure. It is almost incredible, but it is

true, that there was a serious proposal to put a pillar or obelisk on the

top of Arthur Seat as a memorial to the deceased Prince. The propensity to

disfigure peaks in this way is too common.

There are two instances in

East and West Lothian of its being thought right to do honour to the great

by erecting factory chimneys on heights. And one sees the same thing in the

wilds of Perthshire and even in Sutherlandshire. An obelisk high above the

observer is always an eyesore. Such an erection, which may look well enough

against a background, or viewed from a distance on a plain, as in Egypt, is

quite out of place on an eminence, particularly if ęt can only be seen

standing out against the sky. The Martyr's Monument, looked at from North

Bridge, is an instance. I was about to say that no greater outrage could be

commuted against our lovely Arthur Seat than to put a gigantic spike sucking

up into the air on its picturesque summit:. It would indeed be what Lord

Cockburn called "a brutal obelisk." We all know that in one or two aspects

the resemblance of the hill to a lion couchant is very marked. Although

Scotland has the unicorn for its symbol, it could not but be a hideous

disfigurement if a unicorn's horn were set on the head of the lion of Arthur

Seat. Yet such an idea was at one time mooted and gravely considered. But I

am unable to speak of the obelisk as an outrage than which none could be

greater, for a worse and more absurd disfigurement was proposed than that.

After the Prince Consort's death a suggestion was thought worthy to appear

in print, that the memorial to him should take the form of a gigantic crown,

to be built over the lion's head on Arthur Seat! I forget whether it was

proposed it should be gilded, but I can quite believe that anyone who could

moot such a thing, and those to whom the idea commended itself, would have

readily accepted an offer by a house-painter and gilder—desiring an

advertisement— to gild the crown, and fit it with coloured glass jewellery,

which would "have a splendid effect when glittering in the evening sun"! I

feel bound to say that this was not put forward by any member of the

Institute of Architects. But on the same occasion there was an almost

equally objectionable proposal made by a member of that body to erect a

building on Arthur Seat. Will it be believed that ail elevation was prepared

for the erection of a long building, with a horizontal line of roof showing

against the sky on the top of the east part of Arthur Seat immediately above

the Queen's Drive, the elevation showing the line of the building running

east and west? But that such a proposal for the memorial was seriously

tabled I know, for I saw the drawing at the time. The architect who

exhibited it was a most worthy man, whom I respected. It is many years since

he was taken to his rest, a man of "good works," but it is impossible to say

that this work, f executed, could have been called by such a name. It would

have been difficult to imagine anything more objectionable, until to-day,

when one looks at the Caledonian Railway Hotel.

All good citizens have reason

for satisfaction that no one of these proposed monstrosities materialised,

and that the Prince's memory is well represented by the statue in Charlotte

Square, which, however, is rather hid away in its present surroundings.

The next national event which

stirred Edinburgh, along with all the kingdom, was a joyful one—the marriage

of the Prince of Wales, when the greatest enthusiasm was shown. A great

review was held in Queen's Park, and in the evening the city—in which flags

innumerable floated all day, and the fronts of houses were decorated

gaily—there was an illumination which can only be described by the word

"magnificent." It was wisely resolved to abandon the universal lighting up

of houses, and to concentrate effort by obtaining subscriptions to

illuminate the south side of the valley in front of Princes Street, leaving

it to those in charge of large buildings to have special illuminations as

they might see fit. he most striking feature was the lining out of all the

buildings of the Castle with padella lights, to which the crow's-foot

stepped gables lent themselves admirably. The rich, warm tone of the lights,

and the way in which they glittered in the breeze, was as beautiful a

display as could be conceived, the effect being enhanced by a torchlight

procession down the diagonal walk from the Esplanade to the foot of the rock

in the gardens. From the Free Church College downwards the same effect was

produced as n the illumination on the occasion of the Queen s first visit to

Edinburgh, candles having been supplied, and the windows crowded with them.

Lord Melville's Monument at one end of George Street, and St. George's

Church at the other, produced a beautiful effect, the latter being

particularly fine, the dome being marked out in lamps with globes, giving a

delightfully soft pearly tone.

Although there were vast

crowds, the control arrangements were most excellent, and no accident of any

kind took place. Only one incident formed, a speck on the glory of this

joyous celebration. A precaution taken by the police was to forbid persons

crossing North Bridge from using the pavement, lest a surging crowd might

push over the balustrade and cause a catastrophe. To prevent risk of this

rule being broken, a number of dragoons from Perthshire were used to patrol

the pavements and keep them clear. Alas! the good-humour of the crowd,

combined with the propensity of the people to carry whisky bottles, led to

constant kindly offers of drink to the soldiers, and as I saw them when

going back to barracks several were reeling in their saddles, and, more

painful still, a cab followed with some who could not keep their seats at

all. Tbis was not to be wondered at, when what is called "refreshment" was

forced upon the troopers every few minutes.

The officer in command said

afterwards that he himself was urged to accept a dram several dozens of

times during the hours he was on duty. It is not a very pleasing incident to

speak of, but it ought to be recorded as a warning to people not so

inconsiderately to put temptation in the way of men on duty.

Nothing could exceed the

enthusiasm that day. Even had the people of Edinburgh seen the Princess

before her wedding, and come to know her charm of person and of character,

they could not have been stimulated to any higher expression of their good

wishes than was shewn. Those who were present will never forget the scenes

they witnessed.

When the first part of the

Scottish Museum, now the Royal Scottish, was built, lt was opened by the

late Duke of Edinburgh. The Museum has since been completed, and is worthy

of Scotland, and the building is worthy of the city.

I witnessed a most amusing

scene on the occasion. There was a dais set at the end of the great hall for

His Royal Highness, the usual red baize cloth being laid down the building

for a long distance. Rows of chairs were placed on each side, to which the

bailies' and town councillors wives and other ladies were brought forward,

the gentlemen with them retiring and standing behind. Lady Ruthven, an old

dowager who was very deaf, was seated in one of the chairs among the

municipal ladies, and while we waited a gentleman who knew her came up and

shook hands and said into her ear, "I hope your ladyship is comfortable," to

which she replied in the loud tones so common from deaf people, "Oh yes, I'm

all right—I don't: think very much of my surroundings, though." She was an

amusing and lively old lady. Once in an English hotel she came down in the

morning, and accosting the landlord in loud tones, drawing the attention of

those standing by, declared she must leave as she had been so troubled by

fleas during the night. "Oh, I assure you, my lady," was the reply of the

landlord, rubbing his hands one over the other, "it must be a mistake; there

is not a single one in the house." "Quite right, quite right," shouted she,

"not a single one, all married and with large families."

In the course of the Sixties

of last century a movement of serious import to the peace of Great Britain

developed itself. Fenianism in Ireland, aided from the United States, where

the Irish Press preached violence and even assassination, eruptions of which

were seen in the Manchester murder, the Clerkenwell outrage, the attempt to

blow up the Glasgow great gasometer, and the explosions in Westminster Hall

and at London Badge, caused a considerable development of alarm in the

community. The secret information possessed by the Government led to

encouragement being given to local authorities to form corps of special

constables. The Lord Provost and magistrates of Edinburgh did me the honour

to grant their commission to me to take the command of the special

constables enrolled in Edinburgh, whose numbers within a very few clays rose

to 4500, and for a time nightly drill was carried on to give these citizens

the training necessary for compact working in dealing with mobs.

I enjoyed that tune greatly.

There was something not to be analysed in the satisfaction I had of

being—while still little over thirty—"Boss" to many hundreds of grey-haired

advocates and W.S.s, and S.S.C.s and C.A.'s, and merchants of all degrees,

and to order them about. How they submitted is a wonder to me to this day,

as also it was a wonder how quickly they took up formations and performed

movements. And the loyal aid I received from district superintendents, many

of them very senior to me both personally and in experience, something that

I acknowledge now with gratitude. I still cherish my ordinary constable's

baton, which was the only symbol of my office. Fortunately our services were

not required, The demonstration was sufficient. Without it there might have

been serious trouble.

Some years later I had

another experience of the Fenian period, when the conspirators who planned

the blownig up of the Glasgow gasometer were brought to Edinburgh for trial.

The arrangements to prevent surprise and rescue were most elaborate. The

prison van was timed to reach a station near Glasgow only a few minutes

before it was to receive its load of prisoners, and was attached to a train

to take it back to Edinburgh. At Princes Street Station there was a van with

four horses ready to meet the prisoners, escorted by a body of mounted

police with revolvers in their belts. I was one of the Scottish Prison

Commissioners at the time, and drove from the station to the Parliament

Square, where the accused men were to be confined the prison below the

Justiciary Court, on which a guard of soldiers was set. When the prisoners

had been released from their handcuffs I went forward, and, as was my duty,

told them that I was a Prison Commissioner, and asked them if any of them

wished to say anything, And here occurred one of those ludicrous

anticlimaxes that occur on solemn occasions. The only reply I got was from

the oldest of the men, in perfectly serious tone: "Indade, sor, oi think we

ought to have some refrishment!" Fortunately I have considerable command of

my countenance, and carefully avoided looking at any of the police and

turnkeys, fearing there might be an explosion, different from that which the

conspirators had planned. |