|

"The evil that meni do lives

after them."

SHAKESi'ERE.

1840 - 1850

I may be interesting to those

who cannot see so far back as a septuagenarian can, to know something of

what Edinburgh was like seventy years ago. Speaking from the memory of

childhood, it is possible to give an impartial statement of the facts, as

the child mind does not trouble itself with architectural or esthetic

subjects. Let me endeavour to bring a picture of Edinburgh about 1845 before

the reader. Any comment that is made on the facts of course an expression of

thought of later date. We shall start an itinerary from what might be called

then the centre of Edinburgh—the Mound which was made some time before that

to cross the valley of the "Nor Loch." The road at that time went by the

east side, over the space now occupied by the National Gallery ground. West

of this there was a wide, unkept space, which on Saturdays and holidays was

the resort of low-class entertainers, who put down roulette tables, stands

where darts were fired at targets by the explosion of percussion-caps in toy

guns, cocoanut-shies, swings, tables where vendors sold what was called

"Turkey Rhubarb," and cakes of chemicals by which brass could be turned into

silver, for—well —say, twenty-four hours. Shoe-ties, penny toys, and

sweets—the "gundy'' and "gib'' of Edinburgh —were hawked by hand, and small

dogs, honestly or dishonestly come by, were offered for sale to the ladies.

They resounded with cries. "Spoor it doon, and try your luck! " shouted the

roulette man as he spun his wheel; "one to one upon the red, three to one

upon the blue, six to one upon the yellow, and twelve to one upon the royal

crown." "Try a shot, only a penny," came from the target proprietor; "nuts

for your money, and sport for nothing." "Three shies a penny," chirped the

lady at the cocoanut stand. "Cure for colic, stomach-ache, rheumatism,

headache," and several other ills named, solemnly announced the Rhubarb man,

who had the Semitic written all over him. "If", said he, "any gentleman s

troubled with any of the diseases I have mentioned, I'll give him a dose of

Turkey Rhubarb, and if he be not cured within five minits, vie standin'

'ere, I forfight all you see upon this stend." One old man—blind really or

by profession—swung back and forward rhythmically, shrilly announcing,

"Shoe-Mes at a penny the pair, and reeleeg ous tracts at a ha'penny the

piece." A spectacle vendor exhibited his glasses in a case, hung on the

ratings, and a bird dealer sold linnets in paper bags. Of course it will be

understood that I am not speaking only of the first years of the Forties.

These veritable memories belong to a period of some years, and are put

together to give an idea of how the beautiful centre of Edinburgh was

allowed to be degraded into a scene of low-class trade and entertainment

more or less discreditable to the city. No wonder Lord Cockburn said of the

Mound, "that receptacle of all things has long been disreputable."

But this was not all. On the

west side of the Mound there were four wooden erections for which the

fathers of the city were not ashamed to draw rents to bring a little to the

Corporation's bankrupt money-chest. In the middle stood a great circular

booth, of cheese-like proportions, all black with pitch, except where, 1n

enormous white letters, it was announced to Princes Street that this

abomination was the Royal Rotunda. There my infant mind was instructed in

the features of the Battle of Waterloo, by a panorama, the pictures of which

were probably as unlike as they could be to what actually happened on that

field. Farther up the slope was a building even more disgraceful, a penny or

twopenny gaff theatre, which had the distinguished name of ' he Victoria

Temple, of which It is needless to say that I was never permitted to see the

interior. The outside I remember—brown woodwork, and wooden flat pillars,

painted to lmitate—and imitating very badly—the beauties of Aberdeen red

granite. Above this incredible as it may seem, was a tanner's yard! At the

bottom was a coachbuilder's wooden shed and yard, and in front stood

vehicles in various stages of dilapidation and repair. A circle of stones

was set on the ground, at which the hammering of tires on to wheels was

something for the boys to watch.

Special shows were sometimes

permitted to occupy the open parts of the Mound even opposite the Royal

Institution. I was taken to see Wombwell's Menagerie there, and had great

delight. I can think now how hideously disfiguring those yellow vans, and

the gilded front with its lion-tamer pictures, must have looked, as they

blocked the view of the Castle to the pedestrian on Princes Street. When one

recalls this picture of degradation of what by Nature is one o f the most

exquisite scenes which ever gave glory to a city, it is impossible not to

marvel at the utter want of taste and sense and decent regard for

appearance, and even for morality, which were displayed by the civic fathers

of those days, and yet as William Black's golfer, after dreaming that he was

in hell-bunker, said, "But it micht hae been waur". For incredible as it may

seem, it was gravely considered whether a two-sided street should not be

built on the Mound, with the backs of the houses looking east and west to

Princes Street, to the complete run of the view in both directions. Again,

it was only by a determined struggle that the city was saved from the

absolute destruction of its amenity, when the Town Council determined to

build a south side to Princes Street. This would have been irretrievable

loss to Edinburgh as a resort, and a standing disgrace to its inhabitants.

A. street across the valley, up the Mound, would have been scarcely less a

work of outrage. In passing, it may be recalled that an equally monstrous

outrage was brought forward when it was proposed to widen the North Bridge.

A scheme was set on foot and gravely considered for building shops on both

sides of the bridge, right across the valley And worst of all, it was only

by strenuous efforts of a lady citizen that a plot to put some twenty brick

shanties on the side of the slope below the Castle Esplanade, in full view

of Princes Street, was defeated.

Coming to Princes Street, it

was in my earliest days a narrow way, made narrower by the cabmen being

allowed to keep their horses' noses well out into the street, ready to have

a rush across whenever a hand was held up. It was amusing to us little

people to see these short and sharp races. The drvers at the horses heads,

with the whip going back from the left hand, stood watching. All in a

moment, two would dash across, regardless of other traffic, lashing their

horses with wild back swings of the left hand. The language of the loser of

the race was what the reader may imagine for himself.

The Princes Street buildings

were in all stages of alteration. Originally built—as may still be seen here

and there—with the flattest and baldest fronts, the effect was utterly dull

and uninteresting. The houses were all residential, and when they came to be

altered to shops the ground-floor was occupied by one tradesman and the area

by another. To-day there is scarcely a specimen left, but one there is still

that used to be the fashionable fruit-shop of Boyd & Bayne opposite Waverley

Station, a curiosity of the past. In those days the street was utterly

uninteresting and mean to a degree; its only attraction being the outlook to

the old town and the Castle. Some worthy buildings have taken the place of

the old bald fronts, and some, it must be confessed, by no means worthy; but

the general effect is much better than in the days when the street presented

uniformity. It was uniformity which was not dignified—paltry and inartistic.

As for the valley in front of

Princes Street, it presented a sorry sight. What might have been a beautiful

sheet of natural water — the Nor' Loch—was left :n a state of filth and

insanitary accumulation; what in Scotland is called a "free toom," into

which garbage of all kinds—cast-off clothes, dead dogs, and worried cats,

&c.— -were thrown. A filthy marsh, it was the assembling parade, of the

militant boys, where class fights took place freely, and foul matter

abounded, to foster the germs of disease. This may seem an exaggerated

picture, but here is Lord Cock burn's account of the state of things, just

before the formation of the garden was undertaken: "A fetid and festering

marsh, the receptacle for skinned horses, hanged dogs, frogs, and worried

cats. The presence of the water was looked upon as a nuisance, as well it

might be, when the municipal eye looked at it as t was, instead of as it

should be. But apparently the Corporation had little thought of "anointing

the eye with eye-salve, that it might see how the desolate might be made "to

blossom as the rose." Something may be said later as to what has happened in

that valley, and as to what might have happened, if thought and discernment

had been present with the wise rulers. Also it will be seen what golden

opportunities were lost, and what irreparable mischief was done.

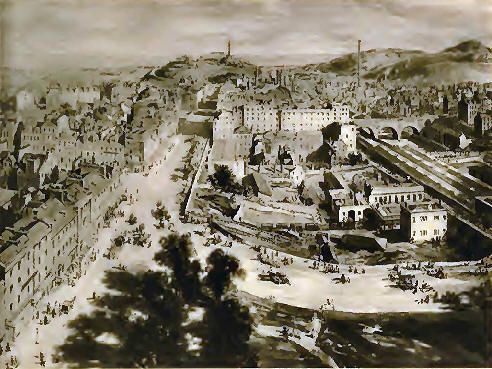

EDINBURGH FROM SCOTT MONUMENT, LOOKING WEST, 1847

Meanwhile, I return to the

child-days—to describe what the child saw, and I take the time when the

Walter Scott monument was built, as it marks a period when recoiled ion is

vivid. At that time, immediately below the site of the monument, there was a

cottage, with a potato-garden surrounding it, of which all that can be said

is that it was not so offensive as what's there now, and certainly not so

offensive as a walled in and paved vegetable market, which was one of the

schemes considered to be sensible by some, and would have been carried out

in all probability but for the demand of the railway interest, which in this

one particular saved the city from a grevous dis-figurernent. In what are

now the West Princess Street Gardens, the part next the street was kept for

amenity ground; but I saw when I was a child the space below the Castle Rock

ploughed down and bearing a crop of excellent turnips. When the weather was

wet, the water formed a loch in the low ground, in which much offensive

matter accumulated. Altogether the valley, which should have been regarded

as a beautiful foreground for the old town and the Castle Rock, was

neglected, and its capabilities for adding to the beauty of the city

remained unconsidered. Indeed, there was at one time, as Lord Cockburn

mentions, a scheme for filling up the valley with spoil and rubbish, the

Lord Provost of the day, when remonstrated with, giving as an unanswerable

reason that it would provide ground for "building more streets"!

Such was the centre of the

town in these olden days, a jewel besmirched with what was defiling, because

those who had it in charge could see nothing worth preserving in it. Like

chanticleer in the fable, who found a beautiful string of precious pearls

when scratching «n the dung-heap, and said he would not give a good handful

of corn for the whole gewgaw, so our representatives saw not the value of

their jewel, and were ready to sacrifice it to the railway moloch It is to a

Lord Provost who said in the Council, without raising even a murmur of

dissent: "Nature has framed this place for a railway station,' that we owe

the fact that what might have been a lovely garden, with a beautiful piece

of water in it, lying n the very bosom of the city, presents now to the eye

its dismal thirteen acres of dirty brown glass and its semaphore

signal-posts, and has many lines of rails running along the base of the old

town hill and the Castle Rock, and hideous signals and signal-boxes

disfiguring the valley perhaps the most unaesthetic mode of laying out

such a piece of ground that human perversity could devise. If Lord Cockburn

could speak of the proposal for a small railway station as "a lamentable and

irreparable blunder,'' what is to be said now when it has practically

swallowed up the whole breadth and half the length of the valley? One can

well believe that if the worthy Lord Provost had known what was to follow,

he would have hesitated to say what he did. Lord Cockburn thought that it

was not intended to express approbation of those worlds of stations, booths,

coal-depots, and stores, and waggons, and stairs by which the eastern

portion of the valley has been nearly destroyed." It's now totally

destroyed. People say, "What's the use of crying over spilt milk?" That's

all very well, but it is only the loss of the milk that is considered, and

it was only by accident that the loss took place. It would be a most futile

consolation if the milk could never be wiped up, and the carpet on which it

fell brought back to its pristine neatness. But when the most disfiguring

things- —the dirty glass, and the formal rails and the signal appliances are

put down—where Nature, aided by cultivation, should for ever have held sway,

presenting a thing of beauty—so that there they must remain in their

hideousness to the end of tune, and this not by an accident, but by the

wilful doing of those who should have shielded the citizens from such an

affliction, one feels almost justified in suggesting that a certain bronze

statue of a former Lord Provost, which if supposed to adorn Princes Street,

should be turned round, so that it may be compelled to face what the mans

life represents assisted to bring about, when he thoughtlessly accused

Nature of having prepared a place for the perpetration of such a wrong to

our beautiful city. Uncle Toby said: "Wipe it up, and say no more about it."

Alas! we cannot wipe it up, and as to saying no more about it, we are surely

at least entitled, when the stranger within our gates sees this

disfigurement, to assure him that we are ashamed, and groan over our

impotence which compels us to bear the sight of such wounds and bruises

deliberately inflicted on the lovely face of our incomparable Edina.

When there is so much to

record of what is unsatisfactory regarding the conservation of the amemty of

Edinburgh, what is good must not be overlooked. A great improvement was made

on the view from Princes Street, which had been terribly disfigured by a

building discreditable in every respect to the architect who planned it—the

Bank of Scotland, of which Lord Cockburn spoke as "a prominent deformity."

Prominent it was, and bulking large in view. !t had not one single feature

to commend it, and least of all to recommend it for the site on which it was

placed. It was really an eyesore. The evil was remedied by its being

enveloped in a new building, which may be said to be worthy of the site, and

now that it is well weathered/ does not offend the eye as did the great

packing-case front of former days, to which weathering only added more

offensiveness. After this improvement, the slope running down from the

Castle, except for the building next the Free Church College on the west,

presented no objectionable feature, unless it were the huge monotonous back

viiew of the City Chambers, which cannot be said to be ornamental, but for

which the own Council of our day were not responsible. It is to be hoped

that ere long this great, almost factory-like square-windowed wall will be

dealt with, so as to break it up and give it a face morein harmony with the

almost Nuremberg character of the other buildings on the slope. Speaking of

the Council Chambers leads me to say something about Cockburn Street, which

was made to give a new access to the old town from Princes Street, a

much-needed improvement to relieve the then existing great hindrance to

traffic on the old narrow North Bridge and the congestion at the Register

House, where all vehicles coming by South Bridge or by Canon-gate to the

Waverley Station and vice versa had to pass round by Princes Street. The new

street being named after Lord Cockburn, Edinburgh's earnest devotee, It was

to be expected that the buildings would be in character with the old houses

on that side of the valley, seeing that he had done all he could—alas, too

often without success—to prevent evil deeds in the valley and beyond it. It

may be admitted that the street is not discreditable to its position. But

one thing was done after it was opened which was little to the credit of our

civic rulers. The south side of the street opposite the City Chambers

consists of a retaining wall, there being a slope of grass between it and

the building. This was for a time allowed to be used as a green for hanging

out clothes to dry, which was bad enough. But there was worse to come. Our

city rulers, who might be expected to be our protectors from the hideous

disfigurement of the ten-foot advertising poster, were not ashamed to let

out this slope that the merits of Pears' Soap and Monkey Brand, &c., or some

other such concoctions, might be proclaimed by flaming placards, shutting

out the slope of grass from view, and vulgarising the street by gaudy,

glaring colours—and all this to draw in a few pounds of rent. It is cause

for thankfulness that—it is to be hoped for very shame—this civic

encouragement to others to disfigure the city was not persisted in for long.

Had it been, the votaries of the poster would have been furnished with an

unanswerable argument against the! own Council at a later date, When they

asked Parliament to give power to veto objectionable advertisements. But

even to-day our rulers are not free from reproach in the matter of

advertising disfigurement, as will be pointed out presently.

The streets which were built

at the same time as Princes Street, George Street, Queen Street, and the

cross streets j lining them, were all in the same bald style, which s only

gradually being broken up, and again to good effect here, and to evil effect

there. Had George Street been built in a well- designed street style, so as

to remain unaltered in front, it would have been one of the finest streets

in the world. Broad, straight, running on a ridge practically level, the eye

earned along by the three statues at the crossings, over a distance

approaching to a mile, and—with a feature which is rare—being complete, the

church at one end and the monument at the other making the finish excellent

at both ends; t has advantages for appearance which are rare indeed. Even

although the buildings are not what they might have been, I know of no other

street that can compare with it, certainly no street in this country.

A good story ;s told

regarding Sir John Steell's bronze group which stands at the east end of

George Street. When the hoarding was being erected for the building of the

plinth, one of two worthy citizens coming along the street asked the other :

"Daursay, whet's that shed

they're pittiii' up noo?"

"Oh," the other replied,

"that's for Alexander and Booceaphihs, ye know."

"Alexander and Booceaphihs! I

wus nut aware that there was a firm of that name in George's Street."

It may give some idea of the

circumscrbed character of the city when I was a child, to mention that there

were country houses, still occupied, where now the city extends far

outwards. In Drummond Place there stood in the middle of the gardens the old

mansion-house of Bellevue, some of the trees of the park being still alive

even now. This house was only removed when the tunnel between Princes Street

and Scotland Street was made for the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railway. I

remember a portion of the tunnel falling in, and being taken to see the

wreck. That must have been in the early Forties. My father remembered when a

farmhouse still stood opposite where Wemyss Place is now, occupied by a

progenitor of Lord Wood; and it is only twenty years ago that a farmhouse

stood at the end of Buckingham Terrace. On the south side, the

EDINBURGH FROM SCOTT MONUMENT, LOOKING EAST, 1847.

Grange House stood in the

fields, and I was taken there when the Dick-Lauder*s were living in it. To

visit it was looked upon as a drive into the country. On the west stood

Drumsheugh House, and farther out East Coates House, and beyond this again

West Coates House, which was in a wooded park, practically on the site of

what is now Grosvenor Crescent, some of the trees in which are to me as old

friends. As children we were often invited to West Coates, as Mr. and Mrs.

George Forbes, my uncle and aunt, lived there. To reach it we drove into a

high-walled lane at the end of Manor Place, and on passing out of sight of

the houses a shout would rise: "Hurrah' now we're in the country." I have

played hide-and-seek round some of the trees now standing in Grosvenor

Crescent gardens, and have many happy recollections associated with dear old

West Coates. Farther out, on the west, was Dairy House. On the east side of

Edinburgh there was a house occupied by Mr. Mitchell Junes —quite close to

Queen's Park—which had the countrified name of "Parson's Green"; on the

north were Inverleith House, and the two Warristons, now far within the

city's boundaries. From these country places I have named, some idea may be

got by the present generation of the extraordinary increase of the city

since the time of my childhood.

But perhaps the most striking

instance of the change that has taken place, is that even now it is possible

to appeal to many persons still living to vouch for the fact that well into

the last century there was at a point, now two miles within the city

boundary, an active colony of rooks. The great trees in Randolph Crescent

were crowded with rooks nests, and some had nests in St. Bernard's Crescent,

and their cawing was not unlike a city concert. Rooks never set up their

rookery in a town; in this case it was the town which enclosed the rookery.

But they held on bravely for some time, and it was only when they became

surrounded by town streets that they withdrew, probably deeply disgusted

with the extension of modern civilisation.

Although, before my time, the

residential quarter of Moray Place, Ainslie Place, and Randolph Crescent,

and the streets off them, had been built, they were by no means complete.

Many corners and gaps were left unbuilt on, and were only gradually filled

up. It must be confessed that although this part of the town is worthily

occupied, it is much to be regretted that the ground was laid off in its

present arrangement. It would have been infinitely better if the alternative

plan had been adopted, of building along the natural terrace formed by the

Water of Leith river, instead of framing that really fine view by the shabby

rubble-walled backs of the houses. Doubtless a greater profit came to the

landowner by adopting the latter design, but a Nemesis followed; for in my

boyhood I often saw in the gardens below the retaining wall and arches,

which the proprietor had to build at enormous expense, when threatened by

the prospect of the foundations giving way, and the great line of houses

sliding down into the river.

It was when I was a very

little boy that 1 used to go before breakfast to see the foundations being

laid of Clarendon Crescent, being the first row of buildings on the north

side of the river, the Dean Bridge having been erected for the purpose of

opening out the Learmonth property for building. It must have been

distressing to the people in Moray Place and Ainslie Place to watch the

gradual closing to them of the beautiful view to the westward by the

building of the crescents and terraces on the other side of the Water of

Leith; although inevitable, it could not but have been a trying experience. |