|

" I remember, I remember,

The house where I was born.

1836 - 40

DECEMBER 27,1836, was the day

on which the light was first seen by yours faithfully. Edinburgh was the

City, and Great King Street the place. Looking back on these seventy-seven

years, recollection goes to something like seventy-four of them, or a little

less. It is remarkable how sharply and how far memory prevails to hold a

picture of the remote past, when an unusual and striking incident has

occurred, even at a very early age of the observer. The first event in my

life in Edinburgh which made an indelible impression was the marriage of a

half-sister, when I was less than four years old. It was a drawing-room

marriage, as was usual in Scotland n those days, and remembrance of it is

clear. I can see the great square footstool on which I sat, and from which

my gaze was concentrated on the bridecake in the corner at one moment, and

at another on the clergyman in his white neckcloth, uttering words that

conveyed nothing to me. I also remember the shower of silver which was

thrown to the crowd as the bride and bridegroom drove away, a custom no

longer in use. The cry of "Pooer oot" is no more heard in the land. A. "pooer

oot" of rice or pasteboard confetti does not draw as did the shower of

coins. All these incidents are quite vivid and real to me, so true it is

that

"Small things long past will

be remembered clear,

When things more weighty and more near

Are waxen dim to us."

This is mentioned, because it

is the very first incident that memory appears to hold, so that it can be

reproduced with certainty. Doubtless, numbers of others are stored up in

that mysterious way, in which room is found on what may be called the

shelves of the brain, for a record of many an event which no personal effort

will revivfy and represent to the; conscious mind, but which some exciting

cause may throw, as by a sudden flash, upon the screen of memory. hat such a

phenomenon does sometimes take place will be exemplified by an incident

which occurred at a later period of life, to be noticed in its proper place.

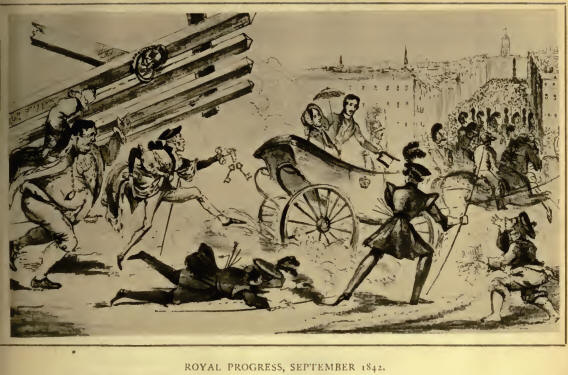

The event which of all others

stamped itself deep on the tablets of my infant mind was the first visit of

Queen Victoria to Scotland in 1842. How well I remember my father taking my

sister and me to a Grand stand erected in what was then a grazing field

between Pitt Street and Brandon Street, and I can recall the exact location

of it by having seen through the space between the floor boards, the filthy

sewage-laden mill stream taken from the Water of Leith, and carried along

the back of Moray Place on to Canonmills, after serving the mills at

Stockbridge. Modern sanitary zeal would have forbidden the placing of a

crowd immediately above such a foul stream, on a stand in which it was to

sit for many hours. Opposite the end of the stand there were erected a

barricade of considerable height, and ponderous gates to represent the City

port of old. These were to be closed until the ceremony had been gone

through of presenting Her Majesty with the silver keys of her ancient loyal

town of Edinburgh. There we sat for several weary hours, until the news

arrived that the entry would not be made till the following morning, and all

had to go home disappointed. Next day early we were once more in the

grandstand, and full of anticipation. Every body expected that there would

be sufficient warning of the approaching procession by the sight of the Lord

Provost and Council in their robes assembling, and the gates being closed.

Suddenly, we saw excitement in Brandon Street—hats waved, and ladies'

handkerchiefs in lively motion, and sounds of loud cheering reached us. A

number of unfortunate people, who had been walking leisurely down between

the crowded lines to reach their stands, were seen running back at full

speed, making first to one side and then to the other, in terror of the

cavalry escort that came on at a full trot, filling the whole space between

the barriers, and before there was time to realise what was happening the

royal carriage swept through the open gateway—no Provost, no keys, no mace,

no sword being there. Quickly as they went by, I .saw the Queen and Prince

distinctly; she in one of the wide spread bonnets of the day, and he with a

very tall hat held in his hand, both bowing first to one side and then to

the other. But it was a twenty seconds' view only; most disappointing to

those who had waited in vain the day before and lost the chance of seeing

her well,—the carriage not be <ng stopped at the gates, and the ceremony of

the keys performed.

History tells us that there

had been a failure of understanding between Sir Robert Peel, the minister in

attendance, and the municipality, the latter not having been informed that

Her Majesty would come up from Granton so early, the hour being about that

of ordinary breakfast time. The contretemps had its amusing side, and two

young ladies drew up, on the same day, a clever skit, winch was sung in many

a street in the evening, and sold in thousands, in which the Lord Provost,

Sir James Forrest, and his bailies were humorously chaffed. The few stanzas

following are a specimen of the song, which is a parody on the old ditty,

"Hey, Johnny Cope." The opening lines were:

"Hey, Jamie Forrest, are ye

waukin yet?

Or are yer bailies snorin' yet?"

There were many verses, but

two may suffice as specimens:

"The frigate guns they loud

did roar,

But louder did the bailies snore;

They thocht it was an unco bore

To rise up early in the morning.

Hey, Jamie Forrest, &c.

The Queen she came to Brandon

Street

The Provost and the keys to meet,

But div ye think that she's to wait

Yer waukin up in the morning.

Hey, Jamie Forrest,

The secret of the authorship

was well kept, and it was not revealed till a few years ago, when it was

learned from Mr. David Scott-Moncrieff that the song was written in

collaboration by his two sisters, who must have been but young girls at the

time. Their witty lines entitle them to be remembered.

All in the grand stand were

struck dumb with disappointment, and once more returned home aggrieved.

Meantime the civic dignitaries, who were leisurely getting into their

carriages to come down in state, hearing with consternation that the Queen

had reached the City, started off at a gallop to try to intercept the

procession on its way to Dalkeith, and pay their respects on the road, They

were not successful, as the cavalcade went at a smart trot, and so they too

came back with woebegone demeanour.

The Queen, on learning what

had happened, good-naturedly altered her itinerary, and devoted a day to an

official entry into Edinburgh. The lofty barricade was removed from

Canonmills Burn to the High Street, and erected across it at the west end of

the City Chambers, The royal carriage I see still, surrounded by the Royal

Archers, the Queen's Bodyguard, who had no chance of doing their duty when

the cavalcade came up from Granton at a trot. The red of the velvet cushion

on which the City keys lay is still with me, seen as I looked down from the

roof of St. Giles', and also the rapid waving of the ladies handkerchiefs

from the top of the long arched gateway in front of the municipal buildings.

All, however, was not

happiness that day. I learned thus early in my life how the joy and the

distressful go together. We were taken after the ceremony to Bank Street, to

a private house, and there from the window saw a sad sight— a dead body and

several stretchers with injured people being taken by the police to the

Infirmary. A grand-stand had been stormed by the crowd, who climbed on to to

it in such numbers that it gave way, and many were precipitated onto the

street. These stretchers I can still see quite vividly before me, and I

remember how the crowd was stilled at the sight.

Of course there was an

illumination at night. Besides the great gas devices at banks and clubs and

colleges, every citizen was expected to fix candles in the frames of his

window-panes, so that each street was one blaze of light. I am ashamed to

confess to-day, for the first time, that we small people, sister and self,

displayed a mean conceit, despising neighbours over the way, some of whom

had a smaller number of candles to the window than we had—an indication that

our vices are not acquired, but are born with us, and have to be overcome.

It may be that the little folks across the street envied us, while we

scorned them. The poet with insight makes envy and contempt relatives when

he speaks of—

"Envy's abhorred child,

Detraction."

They are both propensities to

which childhood is prone. Happy are they whose parents do not foster them by

example, and gently weed them out before the roots go deep.

This domestic illumination

had its charm, every street being lighted up. It would hardly be suitable in

these days, when there is but one candle to each house, fixed in a very

dirty candlestick, and used only for night visits to the coal-cellar. The

illuminations of to-day may be more gorgeous, more magnificent, but those

who remember the "every house" lighting of 1842 will have a memory of

something delightful in its simplisity, and having the charm of the family

expression of loyalty— each house in every street beaming forth its

individual expression of welcome The words "every 9 house" are true as a

general expression, but there was, as in all human affairs, the exception,

which proves the rule. Unlit houses, or houses where there was death or

serious sickness, were not lighted up. In such cases, two men with flambeaux

were stationed on the doorstep. His was a wise, indeed a necessary

precaution. The youthful glazier was out that night with his wallet of

stones, and woe to the windows of the houses that showed no light. As we

little people were being led up towards Princes Street, we laughed with the

malicious glee of childhood when now and again was heard the crash, that

told of window panes broken by the dozen, and perhaps with even greater glee

in one instance, when the windows of a house received their volley, just as

the men with the flam beaux were coming down the street; too late in taking

up their stand to save their employer's glass. Of course we were naughty,

and I doubt not we were told so, although I cannot recall it; for a child's

memory for rebuke is perhaps the least easy to bring up, unless there is the

symbol of a cuff or a slap, or worse, to stimulate recollection. But that we

did enjoy the crashes is some thing indelible on memory's tablet.

Of the greater illumination

devices, some are still remembered, particularly those of the banks and

clubs come up before me. We walked far and we gazed long, without any

appreciation of how time was passing, so delightful was it. to a child to

see so much brilliancy. But it was neither the splendour of the devices, nor

the bright shining of the candle-lighted streets, that excited my infant

surprise to its highest degree that night. When we reached home, the

governess held out her watch to me—I had begun to learn clock-reading —and

my eyes opened wide, and a cry of "Oh!" escaped my lips. It was ten minutes

past ten, and to me the idea of being out of bed till such an hour seemed

overwhelming as an event—something that to my small mind was inconceivable.

And so ended the first great public clay of my life. If my recollections,

though vivid, err in any substantial particular, It is a melancholy comfort

to know that there must be few left who could correct me, and if they d'^d

attempt to do so, I might well meet them by saying that their memory was at

fault and not mine. At least we would agree that, apart from details, it was

a great and a glorious day at the opening of a great and glorious reign.

When Her Majesty visited

Holyrood, she and the Prince inspected the historical rooms without any

ceremony, dispensing with the attendance of their suite. They were duly

shown the supposed stains of Rizzio's blood at the top of the staircase,

down which his body was thrown. When the bed of Queen Mary was pointed out

by the old woman who attended to visitors, the Queen put out her hand to

examine the silk hangings, and was immediately rebuked by a voice saying,"

Yere noll to titch." "But," said the Queen, "you took it in your own hand

just now." The sharp reply was, "Aam allooed to touch it, but naebuddy else

is allooed to tiich it," so the Queen, smiling to the Prince, kept back her

hand. I heard this detailed shortly after it occurred, with my "little

pitchers ears, so can repeat it with a good conscience as a permissible bit

of hearsay. One may wonder if the sour caretaker ever learned who it was

that she had snubbed, and if so, how she felt.

It s amusing to notice that

in the detailed narrative oft! is visit of the Queen to Scotland,was thought

worth while to announce as an amazing circumstance, that the Edinburgh and

Glasgow Railway had conveyed 1175 visitors from Glasgow and the West on the

occasion. Such a figure is now of everyday occurrence. How little was the

revolution that was to take place in public transit by the introduction of

the iron road foreseen then! The possibilities and probabilities did not

enter the public mind. Lord Cockburn, one of the most intelligent and

far-seeing citizens of his time, thought he was giving the free rein to

prophecy when he said in his journal under year

"In twenty years London will

probably be within fifteen hours by land of Edinburgh, and every other place

will be shaking hands, without making a long arm, with its neighbour of only

a county or two off."

It was about the same time,

or not much before it, that a Quarterly Review, sneering at railroads,

declared to readiness to back another Thames against the Greenwich Railway

for speed travelling!

About the time of my birth,

or shortly after, a special Parliamentary Committee sat to consider some

railway questions. One of these was : "What is the route to be taken by the

single line to be made into Scotland?" And there was no one sitting on the

committee, no engineer or promoter-witness, into whose head it entered as a

thought conceivable that there could ever be more than one railway line, and

that a single one, into Scotland. I his I heard stated by Mr. Gladstone <n

the House of Commons in 1887, in a debate on the proposed Channel tunnel in

which he made one of the most interesting speeches I have ever listened to.

At the time when he made this speech, instead of one single line there were

three double lines into Scotland, on which twenty-four fast express trains

ran daily between London and Edinburgh, and many others from the large towns

of England.

1 he above facts are

recorded, as relating to my childhood's time, to indicate how little the

possibilities of a new invention are appreciated. The Edinburgh citizen will

realise this by a concrete example. When the Caledonian line was being

surveyed, the proper direction for it was, beyond all doubt, by Penicuik and

Riggar valley. But one who had been employed as a young engineer in the

laying of it out, assured me that it was not then conceived to be possible

to ascend Liberton hill without the aid of a fixed engine and a rope, and

that this led among other causes, to preference being given to the route

which went through the Carnwath Bog—of all places in the world—m which an

engine was swallowed up shortly after the line was opened, only the end of

the funnel remaining visible.

Another curious fact

illustrating the fear of gradients, is that the East Coast line from

Edinburgh to London was so laid off along the line of the old post road,

that the traveller who supposes he is going southwards to London is, when he

has travelled 28 miles, and reaches Dunbar, 2 miles north of Edinburgh from

whence he started.

Although it takes me out of

Edinburgh, it may interest the reader to get an idea of travelling n the

early Forties, if I say a few words about my first railway journey, when I

was five years old. My father had to go to Madeira with a delicate

half-sister of mine, and he took my own sister and me to London, to live

with my uncle, the Adjutant-General, during his absence, Well do I remember

the excitement as we watched for the railway omnibus that was to take us to

Hay market terminus. The building of the station above ground was then

exactly as it is now. Luggage was passed down to the level of the platform

by a steep shoot of wood, which shone with the polish of many a portmanteau.

With what eager glee I watched a great lady's trunk chasing her own bandbox

down the shoot, and how chagrined I was when the bandbox seemed to me to

take fright and slid over the side of the shoot on to the floor, lust as it

was on the point of being crushed flat against the last heavy package that

had gone down. Railway travelling was then very different from what it s

now. Ours was the important train of the morning, but more than two hours

passed before we descended the tunnel to Queen Street, and completed the

distance of 47˝ miles over one of the most level times in the country,

except at the Glasgow end. It w ill hardly be believed, but—as l saw when I

was older —there was a blackboard at every station, on the Edinburgh and

Glasgow line, on which this rather Irish nocice appeared in bold white

letters: "Passengers are advised to be at the station in good time, as the

Company cannot guarantee that the train will not start before the hour

stated in the Company's Time Tables! The failure to guarantee would rather

be the other way in the twentieth century.

Travelling by steamer to

Liverpool, we were taken on from there by train to Birmingham, which were a

shedule in the middle of the night, being turned out on to the line outside

of the city, the passengers' luggage, which was put un to an open truck,

being pushed along the cinder track in front of us, we following on foot

through the tunnel into the station, where I remember being taken into the

great dining-room, and gazing in wonder at the long line of dishes with all

sorts of cold meats. I hey looked to me like a hundred, having never been in

a public dining-room before. We were, after waiting some time, put into

another tram and carried on to London, arriving early in the morning, after

forty-six hours travelling, little better in time than could be done by a

fast mail-coach. What a contrast to the present day, when the traveller can

leave Edinburgh at 7.45 in the mornmg, be in London from 4.10 to 11.35, and

be back m Edinburgh at 7.10 next morning. Contrast this with the positive

utterance of Sir Henry Herbert in the House of Commons in 1671: "If a man

were to propose to convey us regularly to Edinburgh in coaches in seven

days, and bring us back <n seven more, should we not vote him to Bedlam?"

When railways were

established, and iŤ daily use, there were thousands who vowed that they

would never put a foot in a railway carriage, and there were a few of those

thousands who never did so.

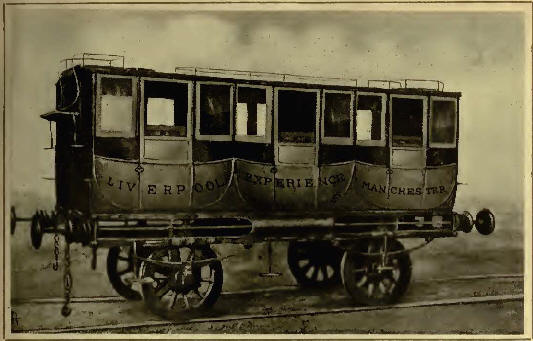

ORIGINAL RAILWAY CARRIAGE

What many people thought

about railways in those early days is illustrated by a scene witnessed when

my father, being in bad health, travelled to Malvern, and my stepmother, for

his sake only, took her place in the train. I see her still, sitting in the

carriage, as we children were taking leave of her. She had her handkerchief

tightly pressed to her eyes, so that she might see nothing, and begged us

not to make her uncover them. Amore abject picture of terror and dejection I

never saw. Four years after this I went a journey with her and all the fear

was gone, and she could chat and laugh like others. I remember her

amusement, and that of other ladies in the compartment, when I showed her

with schoolboy pride my skill in throwing sweetmeats into the air and

catching them in my mouth. All feeling of looking for catastrophe was gone.

In my childhood days I

remember well hearing the denunciations of railroads—their dangers, their

tendencies to injure health, their ruinous effect on trade, their causing

all cows within reach of the railway line to refuse to be milked, their ruin

of the horse-breeding trade, and many other imaginary calamities which were

certain to follow their introduction. It is amusing to find in one's reading

of an earlier period, how the introduction of coaches was denounced. Dickens

gives a fanciful expression of the kind of things said, making one of his

characters in Little Domt say:

Yes—along of them mails, "hey

ought to be prosecuted and fined, them mails. The only wonder is that people

aren't oftener killed by them. They're a public nuisance, them mails. Why, a

native Englishman is put to it every night of his life, to save his life

from them mails.

I came across the other day a

solemn warning sent to a bishop who was about to travel by coach from London

to Edinburgh, begging him to break his journey at York, as numerous cases

had occurred of people who were travelling the whole way, dying of apoplexy

from "the dangerous speed at which these coaches were driven. Just in the

same way were all sorts of evils prophesied as consequences of railway

travelling, and again of motor travelling on roads.

It appears to men to-day a

thing almost incredible that when the transition from coaches running singly

to trains of coaches hauled together, there should have been an absolute

want of imagination and inventive thought, to adapt the style and

construction of the vehicles to the new conditions. Instead of the question

being put to the designer by himself: "How best shall a vehicle be

constructed for the new service?" the thought seems to have been, "How shall

mail-coaches as we have them be dragged along by our engines?" What had

already been done in rail haulage was confined to colliery lines for

conveying coals, therefore it seems to have been assumed that the problem

was how to take a train of trucks and put carnage bodies on them.

Accordingly the. first passenger trains consisted of mail-coaches without

wheels set on trucks, the majority of the passengers being perched on the

top as of old, to face the weather at thirty instead of ten miles an hour,

''here are engravings extant of such trains —some dozen trucks with

mail-coach bodies mounted on the top of them. So unimaginative were those

who regulated the details of railway travelling, that the passengers were

booked by way-bill, a copy of which was handed to the guard, just as was

done in booking for a mail-coach. Even when it was seen to be more sensible

to make carriages for the railroad longer and closed in, the mail-coach idea

did not altogether lose its hold on the designer. I he three compartments of

a carriage had their sides made to bulge out in curves similar to the lines

of the old mail-coach. Such carriages were still running a few years ago on

the South Eastern Railway.* The guard was, as he had been in the mail-coach,

perched upon the top. And as the luggage had been piled on the roof of the

mail-coach, so the luggage was put on the top of the railway carriages. His

practice had not finally been abandoned by the year 1870 on fast express

trains. A burning up of luggage so stowed was not a very uncommon event.

It may surprise the traveller

of to-day, whose train glides smoothly along at speeds of fifty and sixty

miles an hour, to be told that the first lines laid down had square blocks

of stone to support the rails. The first Scottish railway between Edinburgh

and Glasgow was so constructed. The passenger of to-day on that route can

see the stone fences on each side made of these blocks, in which the mark?

of the chairs are still visible. As illustrating the terrible roughness of

such a time, it is told of Mr. Baird, the great ironmaster—Sandy Baird, as

he was commonly called—and whose tongue was not of the most melliifluous,

that on returning from the opening of the Slamannan railway, he replied to a

friend who inquired whether he had enjoyed his trip: f Injyed it, hut, tut;

they puttit me into a first-cless cayridge, and kickit me hard a' the way

doon."

I was not too young when the

railway boom and subsequent slump took place, to be unable to gather up much

from the conversation of my elders. I heard all about Hudson, "the railway

king," and recall a caricature of him seated on a throne, with a poker for

his sceptre, and a circle of eager candidates for shares holding out their

bags of savings, and kneeling in entreaty for allotments. I also remember

seeing a poet :al effusion which opened thus:

"Railway shares, railway

shares,

Hunted by stags and bulls and bears."

My child s curiosity was

aroused to wonder how these animals could be hunters of shares—what ever

shares might be—and had just to take ;t as I got it, in the same way that

the cow jumping over the moon, and a hunt of a spoon by a dish, were ideas

accepted by my childish fancy, hen the idea came home to me when I was

older, and heard of the disaster, when King Hudson lost his crown, and his

worshippers lost their money. People today have no idea of the state of

things that existed then. I remember hearing my father asking that labels be

put upon our luggage, and his being told that passengers must address their

own luggage, as the Company— -which shall be nameless—could not afford to

provide labels! A little later in the Forties I saw every carriage, every

seat, every bell, every luggage truck of the Caledonian Railway, labelled—"Grabbit

and Severn" (the actual names I forget)"Solicitors for the Creditors of the

Caledonian Railway Company." '1 he building of the station in Edinburgh was

stopped when the walls were a few feet high, and rough wooden ticket offices

fitted inside the incomplete edifice, I heard my elders say that many

shareholders, to escape frum further risks, would gladly give their shares

to anyone that would take them off their hands without any price, and many

changed hands for a trifle. The flood of disaster on that line was stayed by

the same "Sandy Baird," walking into the office one morning, and saying: "I

want a wheen shares,'" to the great surprise of those on the other side of

the counter, who asked: "How many shares would you like to buy, Mr. Baird.

"Oh,' said he, "That a haunder thoosand poonds worth." The labels were

washed off the carriages, the seats, the bells, and all the rest, very soon

after that. This "Sandy Baird" was a great character. It is told of him that

when he buiIt a house for himself, he went to a bookseller in Glasgow to get

books to fill the library shelves, and said, when asked what books he would

have : "There Watty Scott, gie me twa dizen o' him, and I'll tak1 a dizzen

o' Willy Shakspere,and a dizzen o' Rabbie Burns," &c., &c.. "And what about

the binding," said the bookseller; "will you have them done in russia or

morocco?" to which Sandy replied: "What fur wud I go to Russiae or Moroccy;

whut fur can I no git them bound in Glesca? |