|

1836-1842.

ORIENTAL SCHOLARSHIP AND SCHOLARS.

Sir W. Jones founds the Bengal Asiatic Society—Sir James Mackintosh and

the Bombay Literary Society—The Early Orientalists of Western India— Dr.

Wilson’s first Address as President—Subordinates his Scholarly to his

directly Missionary Pursuits—Member of the Royal Asiatic Society—The

first to attempt deciphering of the Fourteen Edicts of Asoka—Colonel

James Tod at Gimar—James Prinsep’s Enthusiasm—Dr. Mill—Prinsep’s tribute

to Dr. Wilson—Girnar as it is—The Second and Thirteenth Edicts, and the

early successors of Alexander the Great—Dr. Wilson consulted by

Chief-Justice on Parsee Law and Customs—Congratulatory Letters on “ The

Parsi Religion ” from Erskine and Lassen—Dr. Wilson appointed Honorary

President of the Bombay Asiatic Society—Close of the first period of his

work in Western India.

When Sir William Jones

was sailing across the Indian Ocean, India itself before him, Persia on

his left, and a breeze from Arabia blowing him on, he tells us that “ in

the midst of so noble an amphitheatre, encircled by the vast regions of

Asia,” he resolved to found that greatest successor to the Royal

Society, and the parent of many others—the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In

1784, encouraged by Warren Hastings who declined the office of first

President in his favour, Sir William Jones instituted the first “

Society for inquiring into the history, civil and national, the

antiquities, arts, sciences, and literature of Asia.” His translation of

Sakoontcila had revealed to Europe the virgin mine of Hindoo literature,

as Goethe sang. His greater successor, H. T. Colebrooke, on finally

returning to England, founded the Eoyal Asiatic Society, as well as the

Astronomical Society.

It was not to be expected that Western India, when it grew into

importance as a Presidency by conquest and diplomacy, would be allowed

by men like the Governor Jonathan Duncan, and Mountstuart Elphinstone

and Malcolm afterwards, to remain unrepresented in the republic of

letters. What Sir William Jones, with his fresh English energy and

Oxford zeal, did for the accomplished officials who surrounded Warren

Hastings, Sir James Mackintosh as happily effected among the few who

were associated with Jonathan Duncan. An Inverness boy, a medical

graduate of Aberdeen, an ethical philosopher, a constitutional lawyer,

and a keen politician, Mackintosh leaped into the front rank of the

Liberals as they were at the close of last century. He became the worthy

adversary of Burke, the warm friend of Robert Hall, the advocate of

Peltier who, charged with libelling Napoleon Buonaparte, found in the

impetuous Scot a defender whose oration the first Lord Ellenborough

pronounced the most eloquent he had ever heard in Westminster Hall. Like

Macaulay afterwards, who resembled him in many respects, Mackintosh went

out to Bombay as Recorder, was knighted, and remained there for eight

years, till his friends thought he had saved enough besides earning a

pension. The simple bachelor habits of Jonathan Duncan led him to make

over to the new Judge and his family the principal Government house in

the island, formerly a Jesuit College, known as Parell. Sir James had

not been many months there when, on the 26th November 1804, he summoned

a meeting of friends who established the Literary Society of Bombay. His

Discourse on that occasion mapped out the field of knowledge, moral and

physical, which the observers of Western India were called to cultivate.

He himself, as President, suggested the first philological and

statistical inquiries on a uniform scale, which were not systematically

carried out till, in 1862, Lord Canning directed the adoption, for all

India, of the extended scheme drawn up by Mr. Claude Erskine, the

grandson of Sir James Mackintosh, and by the present writer. That has

culminated in the decennial census, the uniform annual Administration

Reports, and the Gazetteers of the whole Empire of India.

The Literary Society of Bombay soon established a reputation from the

researches of such members as Mr. William Erskine; Colonel Boden,

founder of the Sanskrit Chair at Oxford ; Colonel Briggs, who succeeded

Captain Grant Duff as Resident at Satara; Colonel Vans Kennedy, and

Captain

Basil Hall; besides Elphinstone and Malcolm. Of these Mackintosh became

the literary adviser. To his encouragement we owe such classical works

as Wilks’s Mysore, Elphinstone’s Cabul, Briggs’s Ferishta, Dr. John

Taylor’s Lilawati, and Malcolm’s Political History of India. Moor,

Drummond, Price, Salt, Colonel Sykes, Sir Charles Forbes, Joseph Hammer,

and the erratic Lord Valentia, also adorned that early group, each in

his own way. Sir James urged on the President of the Bengal Asiatic

Society that co-operation for the publication of translations from the

Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian, which, in another form, subsequently

issued in the “Oriental Translation Fund,” the Notices cles Manuscrits

de la Biblio-thlque du Boi, and most fully of all, in the Bibliotheca

Inclica.

But his greatest immediate service was the creation of a Library which,

from the nucleus sent out on his return to England, has grown to be the

most useful, alike for the scholar and the general reader, in all Asia.

That Library gave the Literary Society a new impetus. Besides the papers

which its members contributed to the Bengal and Royal Asiatic Societies,

it published three volumes of Transactions in 1819-1823, and these have

recently been reprinted. In 1830 it was incorporated as the Bombay

Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, and in 1841 it issued independently

the first quarterly number of its Transactions, now a goodly series of

volumes. When Dr. Wilson settled in Bombay he thus found a literary and

scholarly home, to which in a few years he managed to add a museum. Long

after, in 1870, he thus expressed his gratitude :—“ I feel that I am

under very great obligations to this Society. I never could have

prosecuted my studies, such as they have been, without access to such a

Library as that which we here possess. I have often had a hundred

volumes from this Library at the same time in my possession, and though

I have now accumulated a very considerable Oriental library for myself,

I have still frequently to refer to these shelves in order to get my

inquiries satisfied. .... I have also been much sustained by the

literary communion we have here enjoyed. This is not merely the Bombay

Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, but a sort of literary and

scientific club.”

But in truth Dr. Wilson had not been a year in Bombay when he came to be

recognised as the most zealous member of the Society, and soon to be

identified with it as almost the Society itself. In 1830 Sir John

Malcolm proposed him as a member, and from that day his activity was

such that, in 1835, the young Scottish missionary was unanimously

elected President in succession to so ripe a scholar as Colonel Vans

Kennedy. Every tour that he made year by year, every manuscript that he

purchased, every oriental book that he read, contributed material to the

Asiatic Society, which Government royally accommodated in the fine suite

of rooms surrounding the Town Hall of Bombay. Nor did he, in all this

intercourse with scholars, non-Christian as well as Christian, veil for

a moment the earnestness of his own convictions, or restrain his duty as

a missionary. With the then distinguished Orientalist whom he succeeded

as president, he had for years conducted a public controversy. In his

Ancient and Hindu Mythology, and in his Treatise on the Vedanta, Colonel

Yans Kennedy had appeared as something like the apologist of Yedic and

Brahmanical beliefs. While admitting and even eulogising the ability of

these disquisitions as the most learned up to that time, Dr. Wilson

exposed views which he proved to be as superficial as they were hostile

to the work he had come to India to do. But if his hand was the hand of

iron, he ever used the glove of silk. His courtesy, even in the

impetuosity of youth, was as remarkable as his gentle chivalry towards

all when years and toil began to weaken his arm.

Dr. Wilson’s first address as President, on the 27th January 1836,

reviewed the work of the Society and the desiderata of research, from

the similar discourses of Sir James Mackintosh in 1801 and Sir John

Malcolm in 1828, up to that time. He showed that it had failed to

realise the anticipations of the founder as to Natural History and

Statistics. He declared the condition of the people in the different

provinces, as to language, religion, literature, science, art, means of

support, and manners and customs, to be the paramount object of the

Society’s investigation. Beginning with the Parsees, he reviewed the

contributions to a study of them made by Malcolm, Kennedy, Erskine,

Bask, Mohl, Shea, Neumann, and Atkinson, arguing that “should any of the

Parsees, of competent attainments, and real and respectable character

and influence, ask membership of this Society, it should be readily

accorded.”

Such advocacy of the claims of native inquirers and scholars was

characteristic of Dr. "Wilson, and it soon bore fruit. He pointed to

Burnouf as the savant best fitted to translate faithfully the Yandidad

Sade, but plainly hinted that the work might be done in Bombay should

that great scholar fail from the disadvantages of his situation in

Europe. As to Muhammadanism, he desiderated that fuller account of the

state of Arabia at the time of its origin, which Muir and Sprenger soon

after gave, and of the Bohoras and other sectaries whom he himself was

studying. His observations on researches into Hindooism may be read with

profit even after the forty years’ scholarship of Anglo-Indians,

Germans, and Italians. To H. H. Wilson, who had not long been

transferred from Calcutta to Oxford, he looked for a complete

translation of the Big Veda, part of which had appeared first in Bombay;

and of the Bhagavata Parana, the greatest practical authority in the

West of India. On the various Hindoo sects, and on the Jains, he sought

for much light, such as he himself afterwards gave. The despised

aborigines, down-trodden by Hindoo and Muhammadan, and ignored by the

ruling class, save by civilians like Sir Donald M'Leod and missionaries,

Dr. Wilson pronounced “particularly worthy of observation by all who

desire to advance their civilisation, and to elevate them from their

present degradation. Description must precede any considerable efforts

made for their improvement—perhaps leading to important conjectures as

to the ancient history of India.”Many of these“ have had no connection

with Brahmanism except in so far as they may have felt its unhallowed

influence in excluding them from the common privileges of humanity.”

He enlarged on the duty of collecting Sanskrit MSS., a work not

undertaken by Government till a much later date, but now prosecuted with

great zeal and liberality in almost every province. Such manuscripts, he

said, are to be found in a pure state in the Dekhan more than in any

other part of India, and the poverty of the Brahmans leads them readily

to part with them. After eulogising the work of Mr. William Erskine, and

his own old missionary colleague, Dr. Stevenson, in their researches

into the architecture and inscriptions of cave temples, Dr. Wilson said

:—“ We require information as to the time at which, and the views with

which, they were constructed; an estimate of them as works of art, or as

indicative of the resources of those to whom they are to be ascribed ;

and an inquiry into the religious rites and services for which they have

been appropriated, and the moral impressions which they seem fitted to

make on those resorting to them. Grants of land, engraven on copper

plates, are next to them in importance in the advancement of antiquarian

research.”

We find the key-note of Dr. Wilson’s scholarship and erudition in his

reference to “The systems of faith which have so long exercised their

sway in this country, and the various literary works which, though,

unlike those of Greece and Rome, they are of little or 110 use in the

cultivation of taste, are valuable as they illustrate the tendency of

those systems in their connection with social and public life ; and as

they explain a language the most copious in its vocables and powerful in

its grammatical forms, in which any records exist. Destitute of a

knowledge of these systems, and the works in which they are embodied,

the native character and the state of native society will never be

sufficiently understood, a right key obtained to open the native mind,

and all desirable facilities enjoyed for the introduction among the

people of a body of rational and equitable law, and the propagation of

the Gospel, and the promotion of general education. . . . While divine

truth must be propagated with unwavering fidelity, and all hopes of its

ultimate success rest on its own potency, its suitableness to the

general character of man, and the assistance of divine grace, judgment

ought to be employed in the mode of its application to those who vary

much in their creeds and differ much in their moral practice. Though the

great truths proclaimed by the Apostle Paul were the same in all

circumstances, they were introduced in very different ways to the Jewish

Rabbis and people and to the members of the Athenian Areopagus. I must

hold that there is no little unsuitableness in India in addressing a

pantheist as a polytheist and vice versa ; in speaking to a Jain as to a

Brahman; in condemning that at random which the natives may suppose to

be unknown, and in using theological terms and general phrases without

any very definite sense of their application by the natives themselves.

The more a knowledge of Hindooism and of Hindoo literature is possessed

by any teacher, the more patiently and uninterruptedly will he be

listened to by the people, and the more forcibly will he be enabled, and

principally by contrast and concession, to set forth the authority and

the excellence of the doctrines of Christianity.” The address concluded

with a reference to the many Armenians in India, of whom Dr. Wilson

remarked, in allusion to Mr. Dickinson’s dissertation on the antiquity

of their language in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, “There

cannot be a doubt that the Armenians can fill up important blanks in

Church history which, to the undue neglect of the Orientals, is

principally formed on the authority of the Roman and Byzantine Fathers.”

The new President’s Address called forth a request, proposed and

seconded by Mr. Bruce and Mr. Farish, that it should be printed. Mr.

James Prinsep republished it in the fifth volume of the Bengal Asiatic

Society’s Journal, with this introduction—“We make no apology, but

rather feel a pride, in transferring it to our pages entire.” It must be

taken as a directory to Dr. Wilson himself of much that he meant to

overtake, and did more than overtake in the wide area of Orientalism.

The immediate effect of the Address, when it reached Europe, and of the

position in which the young missionary had been placed as the successor

of Sir James Mackintosh, Mr. William Erskine, Sir John Malcolm, and Vans

Kennedy, was his election as a member of the Royal Asiatic Society of

Great Britain and Ireland, on the 18th of June 1836.

We are now in a position to estimate the exact value of Dr. Wilson’s

contribution to the deciphering of the fourteen edicts graven by the

Buddhist Emperor Asoka on the rocks of Girnar and other places in India,

north and east, as well as west. On the 13th March 1835, Dr. Wilson,

hurrying down from the peak of Girnar before the darkness of the night

should come on, examined “the ancient inscriptions which, though never

deciphered, have attracted much attention.” In 1822 Lieutenant-Colonel

James Tod had been the first to notice the antiquities of “the old

fort,” which Joonagurh means, and “the noblest monument of Saurashtra, a

monument speaking in an unknown tongue of other times, and calling to

the Frank ‘ Yedyavan ’ or savant to remove the spell of ignorance in

which it has been enveloped for ages.” But Colonel Tod had contented

himself with directing his old Gooroo, or pundit, to copy two of tlie

edicts, and a portion of a third, while he speculated quite in the dark

as to the author of the inscriptions. Nothing more was heard of the most

interesting historical rock-book in all southern Asia, for the next

thirteen years, till Dr. Wilson stood before it. “After,” he says,

“comparing the letters with several Sanskrita alphabets in my

possession, I found myself able, to my great joy and that of the

Brahmans who were with me, to make out several words, and to decide as

to the probable possibility of making out the whole. The taking a copy

of the inscriptions I found from their extent to be a hopeless task,

but, as Captain Lang had kindly promised to procure a transcript of the

whole for me, I did not regret the circumstance.” He subsequently wrote

thus to James Prinsep :—

“I suggested to Captain Lang a plan for taking a facsimile of the

inscriptions. I recommended him to cover the rock with native paper

slightly moistened, and to trace with ink the depressions corresponding

with the forms of the letters. The idea of using cloth, instead of

paper, was entirely his own : and to that able officer, and his native

assistants, are we indebted for the very correct facsimile which lie

presented to me, and which I forwarded to you some months ago for jour

inspection and use. During the time that it was in Bombay it was mostly

with Mr. Wathen, who got prepared for yourself the reduced transcript,

and with a native, who, at the request of our Asiatic Society, and with

my permission, prepared a copy for M. Jaequet of Paris. I had commenced

the deciphering of it when you kindly communicated to me the discovery

of your alphabet; and I at once determined that you, as was most justly

due, should have the undivided honour of first promulgating its

mysteries. Any little progress which I had made in the attempt to forge

a key, was from the assistance which 1 had received from the alphabets

formerly published in your transeendantly able work, Mr. Elliot’s

Canarese alphabets, and the rigid deductions of Vishnu Shasthi, my

quondam pundit, to whom Mr. Wathen has expressed his obligations in his

paper on some ancient copperplate grants lately sent by him to England.

Vishnu’s palteographical studies, I may mention, commenced with Dr.

Babbington’s paper, which I showed to him some years ago ; and they were

matured under Mr. Wathen. I mention these facts from my desire to act

according to the maxim sunm casque tribuc.

“The rock containing the inscriptions, it should be observed, is about

half a mile to the eastward of [the present town of] Jundgdrli, and

about four miles from the base of Girndr, which is in the same

direction. It marks, I should think, the extremity of the Maryddd of the

sacred mountain. The Jainas, as the successors of the Buddhas, greatly

honour it. They maintain 2)injard2nirs, or brute hospitals, like the

Banyas of Surat, in many of the towns both of the peninsula and province

of Gvjardt; and practise to a great extent the johilopsychy of the long

forgotten, but now restored, edicts of Asoka.”

Dr. Wilson was thus not

only the first scholar to report intelligently on the inscriptions, and

to cause a copy of them to be carefully taken, but to translate “several

words” at first sight, to “commence the deciphering,” and to satisfy

himself that he could probably make out the whole in the leisure of his

study. This his knowledge of Sanskrit, and his toilsome study of

“several ancient Sanskrita alphabets,” lists of which we find in his

rough note-books, enabled him to do. To the last, more brilliant

discoverers devoted to this one work, like James Prinsep and Colonel

Mackenzie, were ignorant of Sanskrit. Prinsep modestly confesses that he

had long despaired of deciphering the famous Samudra Gupta’s inscription

on the Allahabad pillar, from “want of a competent knowledge of Sanscrit.”

Priority in time and mastery of the Sanskrit characters and literature

gave Dr. Wilson an advantage over all the scholars of that day in India.

H. H. Wilson had left Bengal in 1833, and Dr. Mill, on whom his mantle

fell, though translating what General Cunningham calls “several

important inscriptions,” resigned the position of head of Bishop’s

College, Calcutta, in 1837, and in his departure Prinsep bewailed an

irreparable loss. General Cunningham ascribes to Professor Lassen the

honour of having been the first to read “any of these unknown

characters,” on coins at least. A letter from him to James Prinsep shows

that in 1836 the greatest German Orientalist of his day had read the

Indian Pali legend on the square copper coins of Agathokles, as

Agcithulda Raja. But Dr. Wilson’s papers prove that he was even then

familiar with the characters on coins, while this letter does not affect

the credit due to him in the matter of the rock inscriptions.

Captain Lang seems to have delayed for a year the transmission to him of

copies of the Girnar inscriptions. This delay, coupled with Dr. Wilson’s

unselfish regard for others, his devotion to truth in all its forms, and

the fine enthusiasm of the young scholar of Bengal—though five years his

senior—led to the despatch of the facsimiles to Prinsep. The latter was

already partially making the Arian Pali legends of the Bactrian Greek

coins tell their historical tale, and was poring over the Indian Pali

legends of the coins of Surashtra. Mr. Masson had given him the clue

through the Pahlavi signs for Menandrou, Apollodotou, Erinaiou, Basileos,

and Soteros, as he acknowledged in 1835. General Cunningham, his

correspondent and friend even in those early days, admits that “in both

of these achievements the first step towards discovery was made by

others.” That clue led him successfully to recognise sixteen of the

thirty-three consonants of the Arian alphabet, and to give a provisional

translation of the rock inscriptions, before, in April 1840, illness

induced by over-work deprived oriental scholarship of its most promising

ornament.

Now what does James Prinsep himself say of Dr. Wilson in this matter of

the Girnar inscriptions 'I The admission of the missionary scholar’s

merit, previously made when republishing his address as President in the

Bengal Journal, is almost as modest and courteous as Dr. Wilson’s action

had been. It affords a fine example to those orientalists of the present

day who, in Germany, in America, and in England, have sometimes proved

themselves vain controversialists. In 1837 Mr. Watlien had sent to him,

and also to M. Jacquet of Paris—a young orientalist of promise—the

reduced copy of the facsimiles, “which had been taken on cloth by the

Rev. Dr. Wilson.” On 7th March 1838 Prinsep read his paper on the

“Discovery of the name of Antiochus the Great in two of the Edicts of

Asoka, King of India,” nearly three years after Dr. Wilson’s first

partial translation. But he uses this honourable language—“I should

indeed be doing an injustice to Captain Lang, who executed the cloth

facsimile for the President of the Bombay Literary Society, and to Dr.

Wilson himself, who so graciously placed it at my disposal when,

doubtless, he might with little trouble have succeeded himself in

interpreting it much better than I can do, from his well-known

proficiency in the Sanskrit language—it would, I say, be an injustice to

them were I to withhold the publication of what is already prepared for

the press, which may be looked upon as their property and their

discovery, and to mix it with what may hereafter be obtained by a more

accurate survey of the spot.”

Prinsep’s enthusiasm, as he worked his way through these rock

inscriptions in the weeks of February and March 1838, and occasionally

stumbled over the mutilated portions of the facsimiles, led him to

petition the Governor-General to order another rubbing to be taken, and

the Governor of Bombay despatched Lieutenant Postans to the spot. That

officer “took infinite pains to secure exactitude, aided by Captain

Lang, who was with him,” according to Captain Le Grand Jacob’s account.

But, alas ! Prinsep was no more when the MSS. and cloth copies reached

Calcutta. Not till 1870 did General Cunningham stumble upon the

neglected treasures there, although duplicates had been sent to the

Eoyal Asiatic Society. Captain Jacob and Mr. Westergaard made fresh

copies to secure more complete accuracy. The Government of Bombay has of

late shown an intelligent interest in the priceless antiquities of

Western India by appointing an archseological surveyor and reporter so

competent as Mr. J. Burgess, M.E.A.S., and long Dr. Wilson’s friend. His

examination of the Girnar antiquities and his estcimpages of the

inscriptions, as described in his second report, were the most careful

and thorough of all, and may be regarded as final. He sets at rest the

remaining doubts of Professor Weber. After referring to Dr. Wilson’s

first transcript, lie thus describes the stone:—

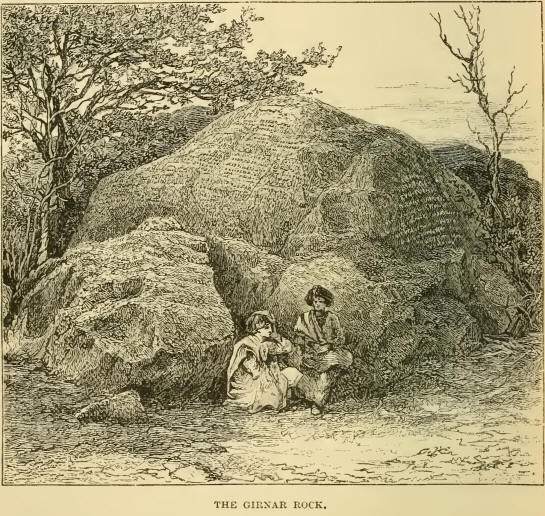

“The Asoka inscription at Girnar covers considerably over a hundred

square feet of the uneven surface of a huge rounded and somewhat conical

granite boulder, rising 12 feet above the surface of the ground, and

about 75 feet in circumference at the base. It occupies the greater

portion of the north-east face, and, as is well known, is divided down

the centre by a vertical line ; on the left, or east side, of which are

the first five edicts or tablets, divided from one another by horizontal

lines ; on the right are the next seven, similarly divided ; the

thirteenth has been placed below the fifth and twelfth, and is

unfortunately damaged; and the fourteenth is placed to the right of the

thirteenth.”

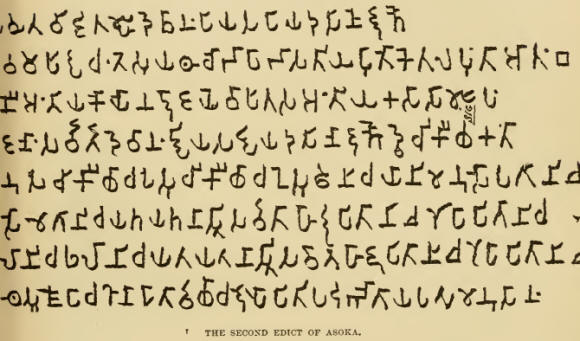

We reproduce

Westergaard’s nearly accurate transcript of the Second Edict, that our

readers may see the characters on which first Dr. Wilson and then James

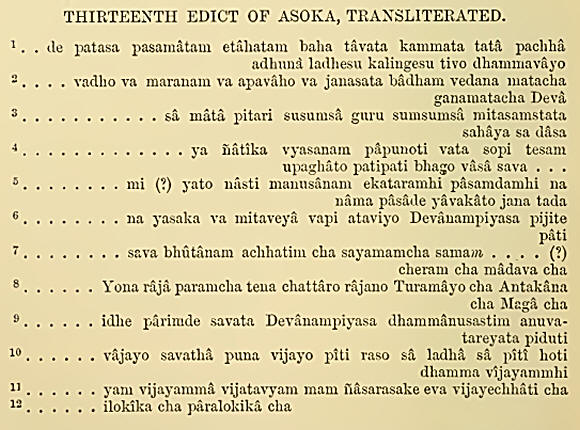

Prinsep worked. The Thirteenth Edict follows, in a transliterated form,

and as mutilated by what Tod calls “the magnificent vanity of Sun-darji,

the horse merchant,” whose people, when making a causeway to the spot

from Joonagurh, seem to have used a part of the fifth as well as of the

thirteenth tablet. Mr. Burgess, in 1869, found the precious Rock

occupied by “a lazy, sanctimonious, naked devotee, whose firewood lay

against the sides of the stone, whilst fragments of broken earthenware

covered the top of it.” The engraving is from a photograph, taken under

his direction, from the wall of the causeway. The Joonagurh chief, a

Muhammadan, has, at the request of Government, now protected the stone

by a roof.

The latest rendering, by

Professor Kern of Leyden, is this:—

“In the whole’dominion of King Devanampriya Priyadarsin, as also in the

adjacent countries, as Cliola (Tanjore), Pandya (Madura), Satyaputra,

Iveralaputra (Malabar), as far as Tamraparni (Ceylon), the kingdom of

Anti-ochns the Grecian king, and of his neighbour kings, the system of

caring for the sick both of men and cattle, followed by King

Devanampriya Priyadarsin, has been everywhere brought into practice ;

and at all places where useful healing herbs for men and cattle were

wanting he has caused them to be brought and planted ; and at all places

where roots and fruits were wanting he has caused them to be brought and

planted ; also he has caused wells to be dug and trees to be planted on

the roads for the benefit of men and cattle.”

This is so mutilated that Professor H. H. Wilson did not venture to

propose a rendering of it while criticising James Prinsep’s. We select

these two out of the fourteen Edicts for purely English readers, because

they form the historical links which connect India with Greece. It is in

the Second Edict that the name of the Yona, Yavan, Ionian or Greek king

Antiochus occurs, that Antiochus II. who died B.C. 247, in the twelfth

year of Priyadarsi’s or Asoka’s reign. Still more reliable is the

Thirteenth Tablet, damaged though it be, for it gives us the names of

other Greek kings in the eighth line—Ptolemaios, Antigonus, and Magas;

and of a fourth to whom Asoka sent embassies which “won from them a

victory not by the sword but by religion.’’

In the address of the Bombay Asiatic Society to Dr. Wilson, before his

departure for Syria, he was thanked by his colleagues “ for facsimile

inscriptions on the Cave Temples at Karli, of which, aided by Prinsep’s

monumental alphabet, it was reserved for your learned associate Dr.

Stevenson and yourself, to be the first decipherers.” As Sir William

Jones was the first to introduce into the chaos of Hindoo literature and

history the magical but very real drop of chronological truth which

developed from the Cliandragupta of the Mudra Rakshasa, the Sandrocuptos

of Athenseus, or Sandracottus of Arrian, so Dr. Wilson brought to light

the inscriptions, in which the greater grandson of Chandragupta had

engraved on the rock, twenty centuries before, the names of the

successors of Alexander in Egypt and the East. The Girnar rock must rank

in historical literature with the Rosetta stone, the Behistun

inscription, and the Accadian brick-libraries of Assyria. Apart from

that, in purely Indian literature it reveals to us, in letters as real

and vivid as the printed page, the character of the great and good

Asoka, who, when ruling over the most extensive empire Hindooism ever

saw, from the eastern uplands of Beliar to the Indian Ocean, and from

the snows of Himalaya to the coasts of Malabar, Coromandel, and Ceylon,

was driven by disgust at the sacerdotal tyranny of the Brahmans to

profess and to propagate Buddhism in the eleventh year of his reign.

Tolerant and enlightened, his edicts alone, as we find them graven on

the rocks from Girnar to Cuttack and the Punjab, justify the title,

happily given to the Constantine of Buddhism by Professor Kern, of Asoka

the Humane.

From the time that he was nominated President of the Bombay Asiatic

Society, Dr. Wilson kept up a somewhat constant correspondence with the

scholars of France and Germany, who looked to him in India for new facts

and materials. Greatest of them all in France, if not throughout Europe,

was the accomplished and accurate Eugene Burnouf, Professor of Sanskrit

in the College de France, who for the first half of this century was

without a rival in the department of Zand. He was the friend, also, of

Mr. Brian Hodgson. In 1840 another French scholar, M. Theodore Pavie, of

L’Ecole des Langues Orientales in Paris, visited Bombay, passing on

thence to Madras and Calcutta, from which, in imperfect English, he

addressed to Dr. Wilson a letter of gratitude for learned counsel and

the gift of a MS. of one of Kalidasa’s dramas. About the same time Mr.

Turnour, the greatest Pali scholar in the East, and afterwards

translator of the MaJiawctnso, “The Genealogy of the Great,” was

introduced to Dr. Wilson. They must have had much to talk of, for it was

Turnour who first identified the Priyadarsi of the Edicts with Asoka, by

“throwing open the hitherto sealed page of the Buddhist historian to the

development of Indian monuments and Puranic records,” as Prinsep

expressed it.

No Government, not even that of the country which rules India, has shown

so enlightened an interest in its literature and religions as that of

Denmark. It was the first to send Protestant missionaries to the Hindoos,

the first to protect the English missionaries whom the East India

Company* persecuted at the end of last century, and the first to

despatch its scholars to the East. Thus Rask had taken from Bombay the

rich collection of MSS., Zand and Pahlavi, which he deposited in

Copenhagen. And in 1841, after mastering these, Professor Westergaard

prepared himself for his critical edition of the Zandavasta by visiting

Bombay where he was Dr. Wilson’s guest, and exploring both Western India

and Persia in a literary sense.

Colonel Dickinson, one of his colleagues in the Asiatic Society, and a

valued servant of the State, offered generous aid to Dr. Wilson in the

purchase of Oriental MSS., while he himself, in letters to his Edinburgh

publisher and to Dr. Brunton, was planning new literary undertakings in

aid or rising out of his missionary work. These were—‘The Conversion of

India and the Means of its Accomplishment;’ ‘The Tribes of Western

India, with Notices of Missionary Labour; ’ 'Poetical Pieces by Anna

Bayne, with a Biographical Sketch of the Author; ’ Memoir of B. C.

Money, Esq.’ To Dr. Brunton he thus wrote on 19th July 1842, of a scheme

afterwards taken up by English biblical scholars and travellers: —“I

have long been talking to our friends here about the propriety of our

attempting to found in Britain a society whose express object shall be

to collect Oriental illustrations of the Scriptures, and to render

available to Europeans the treasures of Church History which are to be

found in the Syriac, Armenian, and other Eastern languages. Had leisure

permitted, you might ere this have received from me a short memoir on

the subject, directing attention to what has occurred respecting it, and

offering a few remarks on the intimations of an international

communication between the Jews and ancient Persians, which are contained

in the writings in the possession of the Zoroastrians of India and of

Yezd and Kerman.”

In 1836 there seems to have been made to Dr. Wilson the first of those

references by the Judges of the Supreme Court as well as the Executive

Government, which afterwards became so frequent and honourable to both,

as well as conducive to the good administration of the country. The

Parsees in India believe that, on their expatriation,' their ancient

code of laws as well as their other religious books were lost. They were

governed internally by their own Punchayat, under rules recognised by

the Government in 1778, which gave that committee the power of beating

offenders with the shoe. But as sectarian divisions spread, and as civil

suits involving religious questions came before the Supreme Court, the

necessity for legislation by the British Government became apparent. Not

till 1865 could all parties agree to such a civil code of marriage,

divorce, and inheritance at least as would be satisfactory. In one of

the numerous disputes in 1835 Dr. Wilson’s knowledge of the Parsee

literature and customs was appealed to by the Chief Justice, who

directed the thanks of the Court to be conveyed to him “ for the clear,

concise, and lucid manner in which you have framed your answers to the

queries submitted to you.”

Dr. Wilson now began to prepare for his homeward tour; for new duty in

the midst of holiday recreation. We may here, most appropriately, give

some of the letters of congratulation addressed to him by the greatest

Orientalists of the day. The learned and amiable William Erskine, who

had translated the Memoirs of the Emperor Baber, and was engaged on the

History of the House of Taimur which he was not to live to complete,

thus wrote to him, linking on the foundation of the Bombay Literary

Society to the more brilliant days of the Asiatic Society :—

“(Edinburgh), 13 St. Bernard's Crescent, 14th November 1843.—My dear Sir

— I received with many thanks your valuable researches and remarks on

the Parsee religion. Your knowledge of the Zand and Pahlavi, with their

cognate languages, has enabled you to do much more, and more correctly,

than any of your predecessors, and no person is so well qualified to

solve the question of the date of the sacred books of the Parsees and

the mode of their composition. You speak more kindly of my surface

investigations than they probably deserve. As to the production of

Ormuzd by Zerwen, you are no doubt right. Go on and enrich the world of

letters, while you think chiefly of the religious world and the

religious benefit of the human race. One of the greatest difficulties

with Orientals, and especially with close religions like the Hindoo and

Parsee, you have in a great measure overcome— that of making them appeal

to reason and reasoning. I consider their entering the field of

controversy, to fight foot to foot, as the great difficulty overcome. It

has always hitherto been the grand obstacle. They have rested in

ignorance, regarding even doubt as criminal.

“The address of the Literary Society of Bombay does honour to you and to

them. I think, at its first meeting, the present Governor, then

Lieutenant Arthur who was with his regiment in India, was made a member,

on the motion of Lord Valentia then at Bombay. Believe me, with much

esteem, my dear Sir, yours very truly, Wm. Erskine.”

“Bonn, 1st of September 1845.—Dear Sir—I have had the gratification of

receiving the valuable present of your learned and important book on the

Parsee Religion, and beg to offer you my sincere thanks for this token

of your attention. Having devoted much time and labour to the study of

the Zand language and the remains of its literature, I need hardly

assure you that I have taken a deep interest in your discussions with

the Parsees. I trust that your labours will mainly contribute to

enlighten the descendants of an ancient people that at present are sunk

into such a deep ignorance of their religion. Believe me, dear Sir, your

most obliged and obedient Servant,

“Chr. Lassen.”

On the 30th December 1842 Dr. Wilson gave in his resignation of

President of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, which he

had filled for seven years. He presented it with a copy of The Tarsi

Religion, which he dedicated to its office-bearers and members in token

of gratitude “for the warm interest which many of them individually have

taken in my labours to disseminate useful, but more especially divine,

knowledge among the natives of this great country, whose present social

and moral condition, as well as past history, it is one of the principal

objects of this Society to investigate and unfold.” He gave it also the

two octavo volumes of the Vandidad in Zand, with Goojaratee translation,

lithographed from his own MS., as containing the doctrinal standards of

the Parsees, and two Cufic inscriptions from the south of Arabia. “It is

not without emotion,” he wrote, “I sever this link which has bound me to

office with the Society.” He was made Honorary President.

The Parsee editors and controversialists were not soothed by the

publication of Dr. Wilson’s book. His almost simultaneous departure gave

them full scope for criticism without fear, and for attack without the

possibility of rejoinder. In his edition of Dr. Haug’s Essays, Dr. E. W.

West correctly states that “ any personal ill-feeling which Dr. Wilson

may have occasioned by his book soon disappeared; but it was many years

before his habitual kindliness and conscientious efforts for the

improvement of the natives of India, regained the confidence of the

Parsees. On his death, however, in 1875, no one felt more deeply than

the Dastoors themselves that they had lost one of their best friends,

and that in controversy with them he had only acted as his duty

compelled him.”

The controversy, and the political, educational, and social influences

that preceded it, had done much to teach the whole community such

lessons of toleration, free discussion, and public virtue, as were

embodied and recognised in Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, who was created a

baronet in 1857. The day after Dr. Wilson sailed from Bombay, all the

worthy of the island, Native and European, united to lay the foundation

of the noble hospital, which bears this inscription:— “This Edifice was

erected as a testimony of devoted loyalty to the Young Queen of the

British Isles, and of unmingled respect for the just and paternal

British Government in India; also, in affectionate and patriotic

solicitude for the welfare of the poor classes of all races among his

countrymen, the British Subjects of Bombay, by Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy,

Knight, the first Native of India honoured with British Knighthood, who

thus hoped to perform a pleasing duty towards his government, his

country, and his people : and, in solemn remembrance of blessings

bestowed, to present this, his offering of religious gratitude to

Almighty God, the Father in Heaven of the Christian, the Hindoo, the

Mahommedan, and the Parsee; with humble, earnest prayer for His

continued care and blessing upon his Children, his Family, his Tribe,

and his Country.” |