|

1836-1842

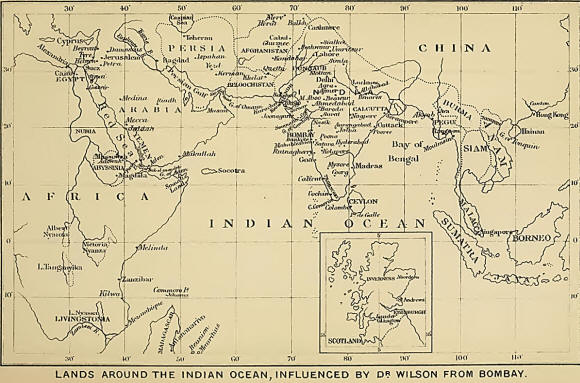

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MISSION.

Civilians and Officers raise a special Fund for the College—First and

Sixth Public Examination of the College — Domestic Slavery in India —

Negro Boys captured from the East African Slavers—An Abyssinian General

and his Sons—Joseph Wollf again—Dr. Wilson on the Government College—

Two Princes from Joanna—What Converts should be supported by the

Mission—First Proposal of a Scottish Mission at Madras—Projected

Missions to Kunjeet Singh and Independent Sikhs—To Kathiawar by Irish

Presbyterian Church—Sir Robert Grant’s Death—Dr. Wilson’s Report on his

Educational System for Lord Elphinstone when Governor of Madras, and for

Ceylon—Proposal to send Missionary to the Jews of Arabia and India—First

Meeting with Mr. David Sassoon—Female Education and the Misses

Bayne—Major Jameson establishes the Ladies’ Association in Edinburgh—The

Afghan Policy of the Government of India—Intercourse with the

Heir-Apparent of Dost Muhammad Khan — Dr. Murray Mitchell arrives—Dr.

Duffs Visit—Encouraging Pastoral from the General Assembly —Dr. Wilson’s

Work as a Translator—Dr. Pfander.

In Bombay, as in

Calcutta, the Parsee conversions had established the value of an English

college as an agency for evangelising the educated native youth no less

than as a means of disintegrating the old faiths of Persia and India.

The English laymen, chiefly officials, who had helped to set up the

English school in the Fort in 1832 under Dr. Wilson’s superintendence,

and who gladly formed the corresponding committee of the General

Assembly’s Mission in 1835, did not fail to urge the importance of

English as the medium of teaching and preaching to this special class.

At the end of 1833 eighteen of the best men and highest officials in

Bombay combined to raise a fund for the support of another missionary

who should devote his whole attention to this work; and they instructed

Mr. Webb and Captain Candy, who had gone to England, to select a

missionary of learning and zeal. Civilians like

Messrs. Farish, Townsend, and Campbell; scholars like Captains

Molesworth, Shortrede, and Jacob; and physicians like Drs. Smyttan and

Campbell, with not a few purely military ^officers who were an honour to

the Bombay army, used these words : “ In gratifying this desire of the

natives to learn our language, we would most solicitously provide

against the horrors of irreligion by communicating and recommending the

religion of God. We need, for this object, a man qualified for the

instruction of the natives in the English language, and for the teaching

and preaching, through this medium, the Gospel of Christ. We need a man

qualified to assist the mind now emerging; to draw it forth and lead and

direct it; to mould and form and abidingly fix it. We need a man devoted

to the Lord ; a man of talent, and intelligence, and general information

; of a vigorous and energetic yet patient mind ; of a sober and sound

judgment, of steady and strong selfdenial; of a prayerful and hopeful

spirit, and of great and catholic love—we want a missionary. Oh! how

should we rejoice to behold such a man ; how glowingly should we welcome

him! ” The transfer of the Scottish Mission to the Church of Scotland

had rendered the need less urgent; and Dr. Wilson, while fortunately

continuing to hold unshaken his view of the importance of using the

classical and vernacular languages, threw the whole weight of his

culture and energy for a time into the new Institution. Mr. Nesbit’s

absence at the Cape and Ceylon, from ill-health, made the help of a

colleague more than ever necessary, and for this the special fund was

ready. He studied carefully the experiment of the Baptist missionaries

at Serampore, which was of the same Oriental type as his own, and he was

in close correspondence with the Scottish missionaries at Calcutta.

The first examination of Dr. Wilson’s college has a curious interest, as

described in the public journals of 1836. All the dignitaries of the

island were present, even the leading priests of the Parsee, Hindoo, and

Muhammadan communities, for the conversion case had not yet occurred on

its public side. Dr. Wilson alluded to the difficulties he had only

partially overcome in securing qualified teachers and monitors, and a

sufficient supply of unobjectionable text-books and scientific

apparatus. He anticipated the time as not far distant when the knowledge

thus communicated would bring many natives with their children “ within

the pale of the Church.” By the hope of this he defended his connection

with the Institution as a missionary, and his determination “ to devote

to it a large share of my attention without neglecting other important

duties which harmonise with its objects.” From the reading of the Gospel

of Mark in their native tongue by ten Marathee boys selected from the

primary schools to be educated as teachers, to a theological examination

in the English Shastres, and on natural history and mineralogy by the

highest class, the work of the college was passed under review. The same

Goojaratee papers, which a few months later denounced the college at the

bidding of the sanhedrim because of its necessary and publicly avowed

results in the baptism of its students, were unqualified in their

eulogies. The Chabak or Whip declared that “ all were fully satisfied

that no such progress as that made by the boys of this school within the

eleven months of its existence has ever been exhibited in any

institution in this place.” A knowledge of the Christian Shastres was

liberally put side by side with that of arithmetic, “ man, and other

objects of natural history.” In reporting the examination to Dr. Brunton,

Dr. Wilson wrote:—

“10th November 1836.— .... You will observe that we secure the religious

instruction of all the pupils, even of the boys who have not made so

much progress in English as to use it freely as the medium of

communication. It is my intention not to overlook the cultivation of the

native languages, which have hitherto, to the great prejudice of English

seminaries in India, and to the prevention of their pupils from

benefiting their countrymen by translations, been much neglected. The

Brahmans here have the greatest contempt for some tolerably good English

scholars, because they speak their vernacular tongues like the lowest of

the low, and are unable to compare together the native and European

science and literature. This, I trust, will not be their feeling in

reference to our pupils, if you entertain the view which I have

expressed. The natives have already much confidence in our operations.

As all their own learning flows through the priesthood, many of them

have the idea that all European learning must flow through it also. One

of the most influential of their number, and of the class represented by

party men as hostile to missions, lately oflered me a large sum of money

if I would give himself exclusive attention during a part of every day,

which I of conrse declined to do, as it would place me in a wrong

position with regard to the natives in general.”

With this may be contrasted the facts revealed at the sixth annual

examination in March 1842, when 1446 youths were under instruction. Of

these 568 were in the girls’ vernacular schools, and 723 in the boys’

schools. There were 155 in the college, of whom 78 were Hindoos, 38

Jews, 6 Mussulmans, and 33 Christians of the Eomanist, Armenian, and

Abyssinian, as well as Eeformed Churches. The subjects and text-books

were those of the Scottish Universities, not excluding Greek and Hebrew.

Prize essays were read by natives on domestic reform and the practice of

idolatry. Geology was the science studied that session. Dr. Wilson

lectured on the evidences of Christianity, Biblical Criticism, and

Systematic Divinity.

So early as 1833 Dr. Wilson directed his attention to the slave trade

from East Africa, and to the character of domestic slavery among both

Hindoos and Muhammadans in India. In reply to an appeal from T. H.

Baber, the Bombay Union of Missionaries invited the Moravians or United

Brethren to utilise their experience gained in the West Indies and South

Africa, and their knowledge of industrial occupations, in the formation

of a colony in the Upper Wynaad district of South India, “ to reclaim

the slaves from their present state of ignorance and barbarism.” The

Basel and English missionaries have since done much in mitigating the

oppression of the casteless races of South India by the native

Governments and Brahminical communities, and that with the aid of the

British Government, while Christianity has won her greatest numerical

triumphs among the simple peoples from the Dekhan to Cape Comorin. But,

till so late a time as 1859, it was the custom of the civil courts in

India, more or less ignorantly, to register and treat as legal documents

contracts for the service and sale of slaves, which have been prohibited

ever since. Whatever serfdom or domestic slavery exists in India is

beyond the law, and has ever since been discouraged by the law, as well

as by the special efforts of the police directed to the extirpation of

kidnapping, eunuch-making, and other nameless horrors of the kind. After

the interference of Parliament for the suppression of the African

slave-trade the Indian Navy played its part with a vigour and a humanity

worthy of its reputation, which, till its premature extinction followed

by the revival of a Marine Department, had always been great in

scientific work as well as in maritime warfare.

What was to be done with

the captured slaves who were restored to freedom in Bombay, the

head-quarters of the Navy 2 The Government at once made over those of

school going age to Dr. Wilson, to the number of eight boys and five

girls at Bombay, and five boys at Poona, to begin with, in 1836. The

problem is not yet solved; it has assumed proportions since the Zanzibar

treaty, secured by Dr. Kirk following Sir Bartle Frere, which must issue

in Eastern and Central if not also Western Africa, following the course

of the empire created by the East India Company. But the germ of the

enterprise, which blossomed out into the expeditions of Dr. Livingstone

attended by some of those very slave boys, is to be found in the

eighteen youths of whom Dr. Wilson wrote home at the end of 1836: “There

is reason to hope that they may ultimately prove a blessing to the

Mission, while their capture will teach the native slavers a salutary

lesson.”

In April 1837 we find, similarly, the germ of Lord Kapier’s success in

the Abyssinian Expedition. In the course of those almost chronic

revolutions from which Abyssinia has been rarely free, Michael Warka,

military commander of three towns in Habesh, as it is called, found

himself compelled to take refuge with the British Consul at Massowah,

along with his two sons Gabru and Maricha. When in power Michael Warka

had always shown himself friendly to Mr. Isenberg, Joseph Wolff, and the

Church Missionary Society’s station at Adowah. The father and sons went

on to Bombay, where they became, of course, Dr. Wilson’s guests. The

boys, then seventeen and twelve years of age, read Amharic and its Tigre

dialect with great fluency. Dr. Wilson’s polyglott accomplishments had

not up to this time extended to the tongue of Ethiopia, but Joseph Wolff

accompanied the Abys-sinians, and left with him an Amharic and English

vocabulary, through which they and their teacher at first learned from

each other. “ I trust they are not the only Christians connected with

the Eastern Churches exterior to India who will be placed under our

care,” Dr. Wilson wrote. Wolff disappeared more suo for America, in

order to enter Africa by Liberia, leaving behind him this characteristic

letter :—

“Bombay, 10th April 1836.—My dear Wilson—Knowing that you are a dear

brother of mine, I take the liberty of making the following request to

you. I don’t like to trouble dear Mr. Farish with it, for he does a

great deal for me whilst I am with him in his house. My sickness and

journey, and the circumstance of having been robbed on my return for

Sanaa, obliged me to draw more on Sir Thomas Baring than I think it to

be just to. draw now. With regard to my dear wife, I gave my word to her

worldly brother never to carry on my mission at her expense. I also

don’t know whether all the money for my book has been sent in. If you,

therefore, could procure for my future journey to the Cape some

assistance from Christian friends I should be most obliged to you and to

the friends. I also wish to consult with the brethren here about my

future movements, whether I should pursue my journey to Africa via the

Cape, or go at once to Kokan and Yarkand via Kutch, Kurachee, and

Candahar ? I think if I could obtain 1200 rupees for either journies it

would be abundantly sufficient.—Yours affectionately,

“Joseph Wolff.”

In Dr. Wilson’s correspondence we find these traces of his own college

work, and that of the state institution, the Elphinstone College:—

“30th November 1837.—The Elphinstone College, which is in the immediate

neighbourhood of our school, and which has most^splendid accommodations

and large endowment and Government grants, has only at present eight

pupils. In order to get the number increased its managers have resolved

to found sixteen large scholarships, and to commence an elementary

school. Did it not by its constitution and practice exclude Christianity

I should "wish it success. But while it interdicts the teaching of the

words of salvation I must invite the youth of India to repair to those

seminaries of learning of which the motto is, ‘ The fear of the Lord is

the beginning of knowledge,’ and use all lawful means to induce them to

place themselves under their influence. Of the most important of these

means, in connection with ourselves, is the procuring of suitable

buildings for our Institution.

“28th February 1838.—I am happy to state that the Abyssinians have

conducted themselves in the most becoming manner, and that the progress

which they have made in their studies is most gratifying. Gabru, the

elder boy, you would observe particularly noticed in the account of the

examination of the seminary. He acquitted himself on that occasion

remarkably well, considering the short time that he had been studying

English; and his subsequent advancement has been such as to sustain the

hopes which his appearance led us to cherish. He has superior talents

and a most commendable thirst after knowledge. His brother, though

inferior to him, is also getting on well. I am quite hopeful that good,

which may yet prove to be saving, impressions have been made on both

their minds. Their father returned to his native country on a visit a

few days ago. Had he not been satisfied with the treatment which they

are receiving in Bombay he would not have left them even for a season.

When I expressed to him the hope that his sons might yet be teachers of

primitive Christianity on the mountains of Habesh he seemed much

delighted.

“Of the Zanzibarian children rescued from the Arab slavers, there are

now with me six boys and six girls. Three boys, and these not the least

promising, have been removed by death. Those who remain are learning

English. The most advanced of them is a very promising boy. They all

wish to be considered Christians, though when they came to me they were

Mussulmans. The five boys who are with Mr. Mitchell at Poona are

advancing in every respect. For each of the Zanzibarians we receive

three rupees monthly from the Government, but about double that sum is

needed. The day may be speedily approaching when the interesting objects

of our care and solicitude may prove not only the monuments of the

divine mercy but the instruments of the divine praise in their native

land, or among their benighted countrymen who visit the shores of India.

“Two young princes, aged nineteen and twenty years, nephews of the king

of Hinzuan or Joanna, the African island of which an interesting

description is given by Sir William Jones, came in their own dhow on a

visit to the Government in the month of October. They were first placed

with the Kazee of Bombay ; but in their own broken English they said,

Tat won’t do at all. We come from Hinzuan to see white man, and governor

send us to stay with black man and leaving the Muhammadan judge to his

own meditations they betook themselves to their own vessel in the

harbour. I was then asked to take charge of them, and they became

inmates in my house, in which they continued to stay during the three

months of their visit. We felt a great interest in satisfying their

curiosity connected with the numerous subjects of their inquiry, and

particularly the principles of Christianity ; but though they became

acquainted with the truth to a considerable extent, and seemed sometimes

to feel the force of the arguments against the Koran, they appeared to

the last to cling to their errors. 'What the future effects of our

intercourse may be no one can tell. They carried to their homes the word

of God in Arabic, which they understand. Their knowledge of English,

picked up principally from shipwrecked seamen and occasional visitors,

is considerable; and even their servants had some acquaintance with it.

From what they stated it would appear that it could be propagated

throughout their island without much difficulty. The language most

prevalent with them is the Sowaheli, which is spoken at Zanzibar and

through large districts on the coasts of Madima or Africa. Muhammadanism

they represented as making great progress in those quarters, but

principally through the violence of the Arab colonists, and the agents

of the Imam of Muskat. Their own hatred of idolatry, though they had not

a few superstitions, they made apparent on many occasions. One evening,

after they had accompanied me to some of the Hindoo temples, they had a

curious discussion with a Hindoo gentleman whom they found in the

mission-house on their return: ‘We take walk,’ they said, ‘with Dr.

Wilson, but have got great pain in our stomachs (hearts) because all

Hindoo men are mad, and make salaam to stone god. What for got Governor

? Why not he put you all in prison ? You come to Joanna, then we flog

you.’ The Hindoo, in self-defence, declared that he did not worship

idols. *Then,’ pointing to his sectarial mark, said his princely

instructors, ‘ you double-bad ; you come into Englishman’s house and

say, I wise man, I not worship images ; then you go to your own house

and put on Hindoo god’s mark just ’bove your eyes there. You two-faced

man! ’ With these interesting youths I expect to keep up a

correspondence.”

The growth of the mission raised such questions as that of “alimenting”

or providing for the temporary support of young converts excluded from

their Hindoo and Parsee homes, and fit to be trained in the college for

missionary or educational work. From the first Dr. Wilson drew a clear

and wise distinction between “ promising and select Christian youths

while they study English with a view to our subsequent employment of

them as agents,” and “ native Christians who have nearly reached the

meridian of life.” Practically, he settled the difficulty in the case of

the former by taking them to his own house and table, even up to the end

of his life, judging carefully in every case, but with a kindliness that

left him sorely out of pocket. The village and barrack systems for the

occupation and training of converts, must be judged of according to the

class to be trained and the state of native society from which they have

come. In every case the very appearance of seeming to hold out a bribe

to converts has been carefully eschewed by the Scottish Missions.

In 1832 Dr. Wilson had urged the establishment of a Scottish Mission at

Madras; offering, on behalf of M. R. Cathcart of the Civil Service

there, £150 a year for a time. Not till 1836 was the General Assembly,

moved by Dr. Duff’s return, able to appoint Mr. Anderson there, soon to

be followed by Mr. Johnston and Mr. Braidwood, the last specially sent

out by the Edinburgh Students’ Missionary Association which Dr. Wilson

had established.

The Church of Scotland, influenced by the alliance with Runjeet Singh,

which preceded Lord Auckland’s unfortunate Cabul expedition, projected a

mission to the then independent Sikhs, but Dr. Wilson counselled a first

attempt among those of the protected states of our own territory, such

as the Church Missionary Society and the American Presbyterians

afterwards undertook. He declared his willingness to make a missionary

survey of the Punjab up to the Indus and its tributary streams,

preaching in Hindee and Oordoo or Hindostanee on the way. “ I could

perhaps induce some influential natives to betake themselves to Bombay

or Calcutta for their education. I could furnish you with such a full

report, diversified by notices of the country, people, and prevalent

religious systems, as you could lay before the public for their general

information, and to invite approval and co-operation.” Such a survey,

and the consequent action at that time, would have anticipated by twenty

years the Christianising of the land from the deserts of Rajpootana and

Sindh, at which Dr. Wilson’s influence ceased, to the Sutlej

immediately, and ultimately to Central Asia.

What it was not expedient or possible for his own church to attempt, in

the regions beyond the three settled presidencies, as they then were,

Dr. Wilson induced other churches to undertake. The missionary survey

which he made of Kathiawar co-operated, with the eloquence of Dr. Duff

in Ireland, to lead the three hundred Presbyterian congregations of the

Synod of Ulster, as the Irish Presbyterian Church was called in 1839, to

establish a mission in India. The Rev. George Beilis, the secretary,

asked Dr. Wilson’s counsel in time to report to the Synod of 1840. He

submitted, in reply, an exhaustive report—an apostolic epistle—on the

needs and the advantages of Kathiawar, which thus begins and closes :—

“Bombay, 27th November 1839.—About three years ago I had determined to

memorialise the Synod of Ulster about the propriety of its engaging in

foreign missionary operations in its corporate capacity, and with

special reference to the great and inviting and promising field to which

I am about to direct your attention, and I was led to delay

communicating my views to you only by observing from one of your

missionary reports that you yourselves had been led to determine to send

forth some of your ministers to preach the glad tidings of salvation to

the heathen world, and to make some inquiries—the result of which I

thought it proper to await—at Dr. Philip and some other individuals,

about the particular scene of your operations. When, in April last, I

learned that you had turned your attention to India, I proceeded to

collect some more particular information than I possessed respecting the

district the claims of which I had resolved to plead before the bar of

your Christian compassion and enlightened benevolence. The arduous

duties which I have been called to discharge, and the great trials in

which our mission has been involved since that time, have hitherto

prevented me from accomplishing my purpose. My procrastination you will

easily understand. Cum ad Maleam deflexeris, obliviscere quce sunt domi.

“ .... I say nothing about plans of labour, as your dear brethren and

agents ought personally to inspect the field before particular measures

are resolved upon. It will afford me, and the other members of our

mission, unspeakable pleasure to receive them in Bombay, and to

introduce them to the friends of the Redeemer’s cause particularly

connected with the scene of their labours. We most cordially invite them

to join our ranks, and with us to fight the battles of the Lord in these

high places of the field. Let them come to us ‘ full of faith and the

Holy Ghost, ’ and be prepared both to labour and suffer agreeably to the

Divine will, and the work of the Lord will assuredly prosper in their

own souls, and those of multitudes of their fellow-men. We cannot say to

them, ‘ The fields are already white unto the harvest,’ where the soil

is not even broken ; but we can tell them that the field is both large

and unoccupied, and that when the seed is sown it will prove

incorruptible.”

In 1838 Dr. Wilson lost a personal friend in the death of Sir Robert

Grant, the Governor, of whom one of the native newspapers remarked that

his last act had been to subscribe to the General Assembly’s

Institution—“ the last expression of his regard to the hallowed cause of

education, which ever lay near his heart, which on various occasions he

advocated with surpassing eloquence, and which many of his public

measures were calculated to advance.” In a letter to Miss Bayne the

widowed. Lady Grant wrote—“I have much valued the letter which Dr.

Wilson had the kindness to send to me, and it has interested me often

when nothing else could. May

I be enabled to profit by the lessons given in it.” Under the new

Charter Act Mr. Farish became Acting-Governor, as senior member of

Council. Soon after Dr. Wilson was pleasantly associated for the first

time with a Governor to whose administration he was destined to render

signal services. The young Lord Elphinstone, nephew of the Hon.

Mountstuart Elphinstone, had been appointed Governor of Madras. One of

his earliest acts was to invite a statement of the experience of the

principal educational institutions in India before introducing reforms

into his own Province.

Nor was it only the Madras Government that consulted Dr. Wilson as to an

educational policy. We find in his papers this extract of a letter which

he wrote to the Governor of Ceylon, the Eight Honourable »T. A. Stuart

Mackenzie, dated 28th April 1811.

“It will afford me very great pleasure to write a short epistle to Mr.

Anstruther on the subject of vernacular education, if you will kindly

apologise to him for my intrusion. None of the arrangements connected

with the Indian Governments on the subject of public instruction have

given me a tithe of the gratification which yours in Ceylon have

afforded. Our ‘ boards of education ’ are by far too exclusive, and they

admit no members of practical experience. They despise and disparage

religion, the only available engine of moral reform; and were their

endeavours not in some degree supplemented by our Christian missions, I

should be disposed to question their ultimate safety. With you all seems

right, proper, and judicious ; and it reflects great honour on Lord John

Bussell that he has approved of your scheme. There are many eyes in

India placed on Ceylon as a model Government. In saying this, I do not

mean to make any insinuation against the civil officers of the Company,

who as a body are a most honourable, enlightened, and faithful set of

public servants. It is the simple fact of the intervention of a Company,

which sometimes appears to me to interpose between this great country

and our happy native land a barrier to the full tide of free and

generous British feeling. Direct responsibility to a chartered

corporation—most necessary when infantile adventure required every

guarantee against destructive loss—is a very different thing from direct

responsibility to the Sovereign, nobles, and popular representatives of

our own realm. I express this opinion merely as glancing at the general

interests of philanthropy.”

Nearly twenty years were to pass before, under tlie catholic University

and grant-in-aid systems, the Government of India assumed its proper

relation to all educational enterprise, independent as well as under its

own departments. But Dr. Wilson did not confine his energies to India

and Ceylon. His sympathies had been also all along with the Gaelic

School Society, to which he and other Scotsmen were in the habit of

sending remittances. And, in return, he sought to induce other

committees of his Church than that specially charged with the care of

the India Mission, to evangelise the Jews.

“16)th July 1841.—To Robert Wodrow, Esq., Glasgow.—It is a joint Mission

to the Jews of Arabia and India, having Bombay as its centre, which I

think in present circxi instances most feasible and promising. I will

thank you to direct the particular attention of the General Assembly’s

Committee to the view which I take of the subject, and also of the

friend who has so generously promised to support a missionary at Aden. I

am certain that his views would be forwarded, and not retarded, by the

plan which I venture to suggest. I think that my friend Dr. Smyttan

could easily show the advantages of the scheme which I propose. A

missionary for Bombay would require to direct his particular attention

to the Arabic as well as the Marathee language. I called a meeting of

the principal Arabian Jews, which was held at the house of David

Sassoon, the most opulent merchant of their body. R. T. Webb, Esq.,

Major Jervis, Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Glasgow, and Mr. Kerr were present with

me during the greater part of the time that we were together. We were

very politely received, and obtained much of the information which we

asked, as well as the promise of every assistance being granted to a Jew

whom I have employed to commit to writing whatever he can learn of the

circumstances of his brethren in Yemen, Bussora, Bombay, and other

places. Towards the close of our interview we entered on the infinitely

important question of the Messiahship of Christ, and had an opportunity

of stating the usual arguments for its establishment. They ordered all

their children to leave the room when we first mentioned the name of the

Saviour; and we could not help observing how much more reserved they

appeared in this matter than the Beni-Israel. They otherwise evinced,

however, no improper feeling ; and they freely discussed with us the

different points to which we adverted. I told them of the deputation to

Palestine, the objects of the General Assembly’s Committee, and its

readiness to aid in the instruction of their countrymen ; and they

seemed pleased with the interest which our Church takes in their

welfare. More noble-looking men than they are not to be seen on the

streets of Bombay, where so many tribes of the world have their

representatives.”

Such was the first love of the Church of Scotland in the infancy of its

missions abroad and its evangelical revival at home, that it planned

enterprises in Arabia, in Persia, and on the upper Indus,1 while it

stimulated other churches to take up provinces which its agents had, as

pioneers, surveyed. But in Bombay itself the death of Mrs. Margaret

Wilson had left the many female schools without a head,, although a lady

teacher had been speedily sent out to conduct them; and the development

of the College made it imperative that the long-sought-for colleague,

whom the Christian officials desired to help Dr. Wilson, should be at

once found, the more that Mr. Nesbit had been absent from India for a

time seeking health. Accordingly, Dr. Wilson, early in 1836, had

summoned to his side the Misses Anna and Hay Bayne, on whom he pressed

the claims of their sister’s work as an inheritance of which they were

bound to take possession. These ladies were to be his own guests,

brought out at his own cost, while retaining their independence in all

things. Towards the end of 1837 the sisters arrived in Bombay, and at

their own charges. Very tender and beautiful was the family life in the

Ambrolie mission home, and occasionally in the country house on Malabar

Hill and in that at Mahableshwar, as revealed by the now faded

correspondence, till Hay was married to Mr. Nesbit only to carry on her

missionary work till her premature death in 1848, and Anna was laid

beside her sister Margaret in the Scottish cemetery, her works following

her. Once more did the fast-increasing class of educated Natives of all

sects in Bombay, as well as the native Christian community, see the

purity, the grace, and the intellectual attraction which cultured women

lent to the missionary’s home, making it every year more and more the

centre, and largely the source, of all that was elevating in Bombay

society.

Impressed by the importance of the work, a retired Bombay officer who

had taken part in it, Major St. Clair Jameson, brother of Sheriff

Jameson, had in 1837 issued an appeal to the ladies of Scotland, which

resulted in the formation of the Ladies’ Society for Female Education in

India. That Association, united in 1865 with a similar agency for

Africa, has ever since worked side by side with the Foreign Mission

Committee of the Free Church, and with remarkable success. At Poona, as

well as Bombay, this indispensable side of a vigorous mission was

extended. In a letter to the Rev. G. White, chaplain. of distant

Cawnpore, who was successfully conducting a Female Orphan Asylum there,

Dr. Wilson wrote in 1835, “I am more and more convinced that, in seeking

for the moral renovation of India, we must make greater efforts than we

have yet done to operate upon the female mind. In Christian countries it

is, generally speaking, more on the side of religion than the male mind.

In India it is the stronghold of superstition. Its enlightenment ought

to be an object of first concern with us. You will be happy to hear that

the prejudices against its instruction in Bombay are fast diminishing

among the natives.” In a letter to his Edinburgh agent Dr. Wilson gives

us a contemporary view of the then gathering Afghan expedition. He shows

himself wise, as always, in political questions, while, writing to a

confidential agent, he expresses his opinion with a frankness rare in

his more public communications. For while he was the citizen and the

statesman, the scholar and the philanthropist, he was above all things

the Christian missionary:—

“I am not by any means satisfied of the justice of onr invasion of

Afghanistan. Shah Shnjah (that old cruel monster) has got from our army

6000 volunteers, officered by the Company, to endeavour to reseat him on

the throne of Cabul. Our main army, 13,000 strong, is now assembling on

the banks of the Sutlej, and it is to move to the northward under the

command of Sir Henry Fane. It is entirely composed of Bengal troops. Our

army of reserve, 5000 strong, composed of Bombay troops, is now

mustering in Kutch. Four of the Bombay stations, Sholapore, Kaludgee,

Belgaum, and Dharwar, are in a few days to be occupied by Madras troops.

The large station of Mhow is to have Bombay instead of Bengal troops.

That we should send an army to watch the movements of Russia, Persia,

etc., I fully admit. That we should dethrone Dost Muhammad Khan I

stoutly deny, on the ground of my present information.”

When, three years later, the Afghan iniquity was becoming a tragedy of a

very doleful kind to our arms, our honour, and our prestige in Asia, and

when Dost Muhammad was a state prisoner on parole in Calcutta, where he

might be observed at his devotions on the Course as the gay world rolled

past, his heir-apparent, Haider Khan, was a frequent visitor at Ambrolie.

On the 1st March 1841 Dr. Wilson thus gossips in a letter to Dr. Smyttan

:—

“We have lately had presented to us a hydro-oxygenic microscope, which

cost Ks. GOO. It has been several times exhibited at my house, and has

made a great impression on the natives. Prince Haider Khan, the son of

Dost Muhammad, is coming to see it in a day or two. He and I are great

friends. Should his family ever again be restored to sovereign power, it

will, I think, be favourable to missionary operations. He sat two hours

with Anna and me the other day. He talks nothing but Persian and Pushtoo.

I get on pretty well with him; and the Moonshee Abdool Eahman Khan, whom

you will perhaps remember as a companion of Dadoba Pandurang, makes all

clear when I break down. This young man, by the bye, comes to us every

morning to read the Scriptures. He will, we hope, declare for Christ.

What an accession he would he to our strength!” So grateful was Dost

Muhammad to Dr. Wilson for his kindness to his son when in captivity,

that he declared he would keep the passes open for a visit from the

Padre Saheb, however disturbed the frontier might be. But Haider Khan

never became more than a sensual Afghan, as described in Colonel

Lumsden’s confidential report on the “Mission to Kandahar” in 1856,

although he was always well inclined to the British Government because

of “the manner in which he was treated while a prisoner in Hindostan.”

When in Bombay he had an opportunity of visiting England, of which he

afterwards regretted that he did not avail himself. The late Ameer, Sher

Ali, was his full brother.

The Mr. Mitchell for whom Dr. Wilson wearied, was the Rev. J. Murray

Mitchell, of the University of Aberdeen, which now followed in the wake

of the Universities of Edinburgh and St. Andrews, and, besides him, gave

to India from the same year’s classes the Bev. John Hay, still the able

Telugoo scholar of the London Missionary Society at Yizagapatam, and the

Rev. Dr. Ogilvie, the first missionary of the Established Church of

Scotland at Calcutta. Dr. Murray Mitchell, as in due time he became,

took with him the Classical and Hebrew scholarship with which Aberdeen

and Melvin were associated, while his wife subsequently became a

missionary to the women of Bombay and Calcutta, worthy of her cousins

the Baynes. The arrival of his new colleague towards the end of 1838

gave Dr. Wilson another proof of the confidence and affection of the

Christian officials, who had raised a special fund of £1800 for this

extension of the college operations.

Having roused the whole of Scotland, the north of Ireland, and many

parts of England by his fiery zeal, Dr. Duff returned to Calcutta early

in the year 1840, by wa)r of Bombay. It was necessary for the good of

the Mission in all three cities and for the success of the projected

Irish Mission, that the two distinguished men, still young, should

consult together—Dr. Wilson, now almost worn out by eleven years of

incessant and varied work for his Master; Dr. Duff fresh from home, but

also from labours no less abundant. If, in the course of the many

splendid orations which Dr. Duff had spoken and published in the

previous five years, he had been led by his Calcutta experience

occasionally to seem to Dr. Wilson to underestimate the need for female

education and instruction in the vernacular languages which Western

India at least had demanded, all was forgotten or discussed after a most

brotherly fashion when the two held long converse at Ambrolie.

The General Assembly of the subsequent May addressed an encouraging

pastoral letter to its missionaries, ministers, and elders in India,

signed by the moderator, Dr. Makellar, and the learned Principal Lee,

the clerk. Their generous acknowledgments of the arduous labours of the

missionaries, and co-operation of the chaplains and elders, and the wise

counsels of the document, had so good an effect that a similar

communication might be more frequently sent with the best results both

at home and abroad. After the last Assembly before the Disruption of

1843, Dr. Welsh, second only to Dr. Chalmers in the Church of Scotland

at that time, addressed Dr. Wilson, at the request of the Colonial

Committee, on the subject of the scattered settlers in India, for whom

no spiritual provision was made till the establishment of the

Anglo-Indian Union in 1864.

It is difficult to see how, in the midst of all his other engagements,

Dr. Wilson found time for that translation and publication of books,

which formed in his eyes as important a department as the schools and

even the preaching, because the press fed both.1 So early as 1833 he had

thus justified his expenditure to the directors of the Scottish

Missionary Society, when they were insisting on restricting operations

in Bombay, where the press cost £128 a year; the Goojaratee pundit £20;

the Hindostanee, £36; and the Sanscrit and Marathee, £36 :—

“The Pundits whom I have retained for some time have been required by me

not so much for the purpose of aiding me in my studies—though they are

of course highly xiseful in this respect—but of aiding me in fulfilling

my engagements with the press. During the past year I have composed and

principally written out with my own hand, in the first instance, upwards

of 2000 8vo pages in different languages; and it will be perceived, when

the general inefficiency of native assistants is considered, that the

help which I have enjoyed has been reqtiired for almost merely

mechanical purposes. At present the editing, and in a great degree the

translating, of the Marathee Scriptures, and the editing of the tracts

of the Bombay Tract and Book Society, and the preparation of some

pamphlets, have devolved on me. I have all along paid a considerable

part of my Pundit’s wages independently of the Society.”

Nor was it in Bombay alone or in its languages that Dr. Wilson was

active. Dr. Pfander, the Arabic scholar and controversialist, had

arrived in Calcutta in 1838, and sought his aid in printing the three

Persian treatises before referred to. In the work of translating the

Scriptures into the various vernaculars all the competent Protestant

missionaries in the Province, and scholars like Captains Molesworth and

Candy, gladly gave help. Until there are native scholars, masters of

Greek and Hebrew as well as of their own classical and vernacular

languages, to become to the races of India what Luther was to Germany,

the translations of the Scriptures by foreigners, however learned and

experienced, will require revision every generation. This has been the

case in the century since Dr. Carey began his attempts in northern, and

the Lutherans in southern India. The difficulties caused by such

revisions, required even in the English Bible, are inevitable, until the

Church of India develops its own organisation and life. |