|

1829.

OLD BOMBAY AND ITS GOVERNORS.

The Tyre and Alexandria of the Far East—Early History of

Bombay—Cromwell, Charles II., and the East India Company—The first

Governors—A Free City and Asylum for the Oppressed—Jonathan Duncan—Mountstuart

Elphinstone—Sir John Malcolm—Cotton and the Cotton Duties— India and the

Bombay Presidency Statistics in 1829—The Day of Small Things in

Education—First Protestant Missionaries in BombayI—English Society in

Western India—Testimony of James Forbes—John Wilson’s First Impressions

of Bombay.

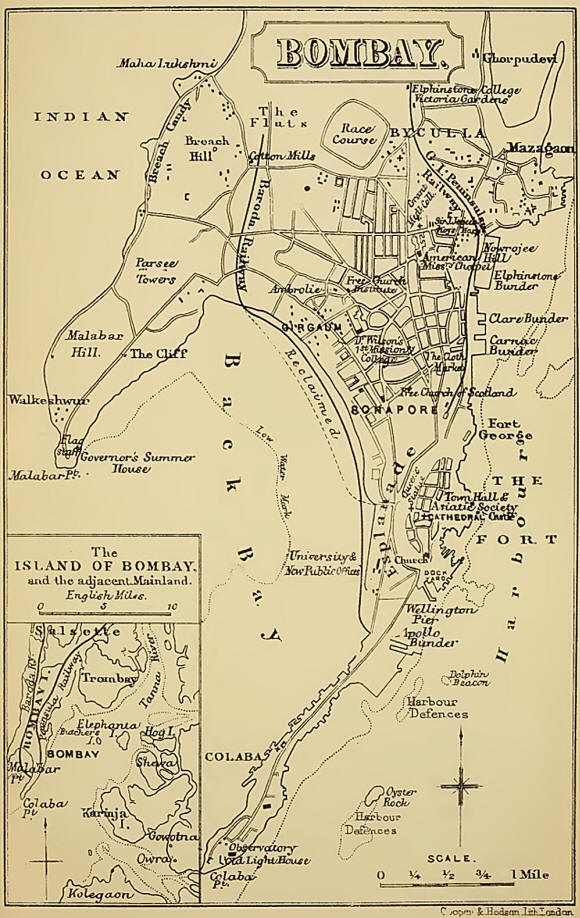

Bombay, with the

marvellous progress of which, as city and province, Wilson was to be

identified during the next forty-seven years, has a history that finds

its true parallels in the Mediterranean emporia of Tyre and Alexandria.

Like the Phoenician “ Eock ” of Baal, which Hiram enlarged and adorned,

the island of the goddess Mumbai or Mahima, “ the Great Mother,” was

originally one of a series of rocks which the British Government has

connected into a long peninsula, with an area of 18 square miles. Like

the greater port which Alexander created to take the place of Tyre, and

called by his own name, Bombay carries in its ships the commerce of the

Mediterranean, opened to it by the Suez Canal, but it bears that also of

the vaster Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. Although it can boast of no

river like the Nile, by which alone Alexandria now exists, Bombay

possesses a natural harbour, peerless alike in West and East, such as

all the capital and the engineering of modern science can never create

for the land of Egypt. Instead of the “ low ” sands which gave Canaan

its name, and the muddy flats of the Nile delta, Bombay presents ridge

after ridge intersecting noble bays, and hill upon hill, rising up into

the guardian range of the Western Ghauts. From their giant defiles and

green terraces fed by the periodic rains, the whole tableland of the

Indian peninsula gently slopes eastward to the Bay of Bengal, seamed by

mighty rivers, and covered by countless forts and villages, the homes of

a toiling population of millions. On one fourth, and that the most

fertile fourth, of the two centuries of Bombay’s history, John Wilson,

more than any other single influence, has left his mark for ever.

From the Periplus, and

from Marco Polo, we learn the commercial prosperity and ecclesiastical

activity, in the earliest times, of the kingdoms of Broach, Callian, and

Tanna, on the mainland and around Bombay. But, as an island, Bombay was

too exposed to the pirates who, from Abyssinia, Arabia and India alike,

scoured these Eastern seas, to be other than neglected. Even the

Portuguese despised it, although, as a naval power, they early made a

settlement there, seeing that it lay between their possessions in the

Persian Gulf and their capital of Goa. But they still held it against

the East India Company, whose agents, exposed to all the exactions of a

Mussulman governor in the factory at Surat, coveted a position where

their ships would make them more independent. Twice they made

ineffectual attempts to take the place, and, in 1G5I, when Cromwell had

given England a vigorous foreign policy, the Directors represented to

him the advantage of asking the Portuguese to cede both Bombay and

Bassein. But although the Protector had exacted a heavy indemnity for

all Prince Rupert had done to injure English commerce, he took hard cash

rather than apparently useless jungle. And, although he beheaded the

Portuguese ambassador’s brother for murder on the very day that the

treaty was signed, there is no evidence that he took any more interest

in the distant and infant settlements in India than was involved in his

general project for a Protestant Council or Propaganda all over the

world. It was left to i Charles II., in 1661, to add Bombay to the

British Empire as part of the Infanta Catherina’s dowry; and to present

it to, the East India Company in 1668, when the first governor, Sir

Gervase Lucas, who had guarded his father in the flight from Naseby, had

failed to prove its value to the Crown. For an annual rent of “£10 in

gold” the island was made over to Mr. Soodyer—deputed, with Streynsham

Master and others, by Sir George Oxenden, the President of Surat—“ in

free and common soccage as of the manor of East Greenwich,” along with

all the Crown property upon it, cash to the amount of £4879 : 7 : 6, and

such political powers as were necessary for its defence and government.

Among the commissioners to whom the management of the infant settlement

fell on Oxenden’s death, is found the name of one Sterling, a Scottish

minister, and thus, in some sense, the only predecessor of John Wilson.

With the succession of Gerald Aungier, as President of Surat and

Governor of the island in 1667, the history of Bombay may be said to

have really begun. It is a happy circumstance that the beginning is

associated -with the names of the few good men who were servants of the

Company, in a generation which was only less licentious than that of the

Stewarts at home, if the temptations of exile be considered. Oxenden,

Aungier, and Streynsham Master ivere the three Governors of high

character and Christian aims, who, at Surat, Bombay and Madras, sought

to purify Anglo-Indian society and to evangelise the natives around.

Bombay, which grew to be a city of 250,000 inhabitants when Wilson

landed in 1829, and contained 650,000 before he passed away, began two

centuries ago with 600 landowners, who were formed into a militia, 100

Brahmans and Hindoos of the trading caste who paid an exemption tax, and

the Company’s first European regiment of 285 men, of whom only 93 were

English. The whole population was little above 5000. A fort was built

and mounted with twenty-one guns, and five small redoubts capped the

principal eminences around. To attract Hindoo weavers and traders of the

Bunya caste, and to mark the new regime as the opposite of the

intolerant zeal of the Portuguese, notice was given all along the coast,

from Diu to Goa, that no one would be compelled to profess Christianity,

and that no Christian or Muhammadan would be allowed to trespass within

the inclosures of the Hindoo traders for the purpose of killing the cow

or any animal, while the Hindoos •would enjoy facilities for burning

their dead and observing their festivals. Forced labour was prohibited,

for no one was to be compelled to carry a burden. Docks were to be made;

manufactures were to be free of tax for a time, and thereafter, when

exported, to pay not more than three and a half per cent. The import

duties were two and a half per cent with a few exceptions. Transit and

market duties of nine per cent, that indirect tax on food and clothing

which the people of India in their simplicity prefer to all other

imposts, supplied the chief revenue for the fortifications and

administration. And it was needed, for “the flats,” which still pollute

Bombay between the two ridges, were the fertile seedbed of cholera and

fever, till in 1864, the first of the many and still continued attempts

at drainage were made. The result of the first twenty years of the

Company’s administration was that Bombay superseded Surat. One half of

all the Company’s shipping loaded at London direct for the island, where

there was, moreover, no Nawab to squeeze half of the profits. The

revenues had increased threefold. The population consisted of 60,000, of

whom a considerable number were Portuguese, and the “Cooly Christians,”

or native fishermen, whom they had baptized as Boman Catholics. In and

around the fort the town stretched for a mile of low thatched houses,

chiefly with the pearl of shells for glass in their windows. The

Portuguese could show the only church. On Malabar/ Hill, where Wilson

was to die, there was a Parsee tomb. The I island of Elephanta was known

not so much for the Cave Temple which he described, as for the carving

of an elephant which gave the place its name, but has long since

disappeared. At Salsette and Bandora the Portuguese held sway yet a

little longer. From Tanna to Bassein their rich Dons revelled in

spacious country seats, fortified and terraced. The Hidalgos of Bassein

reproduced their capital of Lisbon, with Franciscan convents, Jesuit

colleges, and rich libraries, all of which they carefully guarded,

allowing none but Christians to sleep in the town.

The tolerant and liberal policy of the English government of Bombay soon

caused all that, and much more, to be absorbed in their free city, and

to contribute to the growth of the western portion of the new empire. If

to some the toleration promised by Aungier, and amplified by the able

though reckless Sir John Child, seemed to go too far, till it became

virtual intolerance because indifference towards the faith of the ruling

power, the growing public opinion of England corrected that in time. For

the next century the British island became the asylum not only of the

oppressed peoples of the Indian continent, during the anarchy from the

death of Aurungzeb to the triumph of the two brothers Wellesley and

Wellington, but of persecuted communities of western and central Asia,

like the Parsees and Jews, as well as of slave-ridden Abyssinia and

Africa. Made one of the three old Presidencies in 1708, under a later

Oxenden, and subordinated to Calcutta as the seat of the

Governor-General in 1773, Bombay had the good fortune to be governed by

Jonathan Duncan for sixteen years at the beginning of this century.

What this Forfarshire lad, going out to India at sixteen, like Malcolm

afterwards, had done for the peace and prosperity, the education and

progress of Benares, and the four millions around it, he did for Bombay

at a most critical time. Not less than Lord William Bentinck does he

deserve the marble monument which covers his dust in the Bombay

Cathedral, where the figure of Justice is seen inscribing on his urn

these words, “He was a good man and a just,” while two children support

a scroll, on which is written, “Infanticide abolished in Benares and

Kattywar.” Between the thirty-nine years of his uninterrupted service

for the people of India, which closed in 1811, and the forty-seven years

of John Wilson’s not dissimilar labours in the same cause, which began

in 1829, there occurred the administrations, after Sir Evan Nepean, of

the Hon. Mountstuart Elphinstone and Sir John Malcolm, both of the same

great school. Since the negotiations of the Peshwa Baghoba, in 1775,

with the Company, who sought to add Bassein and Salsette to Bombay and

so make it the entrepot of the India and China Seas, the province of

Bombay had grown territorially as the power of the plundering Marathas

waned from internal dissension and the British arms. The first part of

India to become British, the Western Presidency had been the last to

grow into dimensions worthy of a separate government in direct

communication with the home authorities though, in imperial matters

controlled by the Governor-General from Calcutta. Bombay had long been

in a deficit of a million sterling a year or more. But the final

extinction of the Maratha Powers by Lord Hastings in 1822 enabled Bombay

to extend right into Central India and down into the southern Maratha

country, while Poona became the second or inland capital of the

Presidency. The two men who did most to bring this about, and to settle

the condition of India south of the Vindhyas territorially as it now is,

were Mountstuart Elpliinstone and John Malcolm. What they thus made

Bombay Wilson found it, and that it continued to he all through his

life, with the addition of Sindh, to the north, in 1843, and of an

exchange of a county with Madras in the south.

Mountstuart Elpliinstone had no warmer admirer than Wilson, who wrote a

valuable sketch of his life for the local Asiatic Society. A younger son

of the eleventh Lord Elphinstone, and an Edinburgh High School boy, he

went out to India as a “writer” with his cousin John Adam, who was

afterwards interim governor-general. Having miraculous^ escaped the 1799

massacre at Benares, he was made assistant to the British Besident at

Poona, then the Peshwa’s court. He rode b}r the Duke of Wellington’s

side at the victoiy of Assye, as his interpreter, and was told by the

then Colonel Wellesley that he had mistaken his calling, for he was

certainly born a soldier. Subsequent^, after a mission to Cabul, on his

way from Calcutta to Poona to become Resident, he made the friendship of

Henry Martyn. The battle of Kirkee in 1817 punished the Peshwa’s latest

attempt at treachery, and it became Elphinstone’s work to make that

brilliant settlement of the ceded territories which has been the source

of all the happiness of the people since. His report of 1819 stands in

the first rank of Indian state papers, and that is saying much. When,

after that, he discovered the plot of certain Maratha Brahmans to murder

all the English in Poona and Satara, the man who was beloved by the mass

of the natives for his kindl}T genialit}^ saved the public peace by

executing the ringleaders. His prompt firmness astounded Sir Evan

Nepean, whom he afterwards succeeded as governor, into advising him that

he should ask for an act of indemnit}'. The reply was characteristic of

his whole career—“Punish me if I have done wrong; if I have done right I

need no act of indemnity.” The eight years’ administration of this good

man, and great scholar and statesman, were so marked b}T wisdom and

success, following a previous^ brilliant career, that on his retiring to

his native country he had the unique honour of being twice offered the

position of Governor-General. What he did for oriental learning and

education, and how his nephew afterwards governed Bombay, and became

Wilson’s friend in the more trying times of 1857, we shall see.

Sir John Malcolm, too, had his embassage to Persia, and his ; victory in

battle—Mahidpore; while it fell to him to complete that settlement of

Central India in 1818 with Bajee Rao, which the adopted son, Nana

Dhoondopunt, tried vainly to upset in 1857. Malcolm’s generosity on that

occasion has been much questioned, but it had Elphinstone’s approval.

His distinguished services of forty years were rewarded by his being

made Elphinstone’s successor as governor of Bombay in 1827. In the ship

in which he returned to take up the appointment was a young cadet, now

Sir H. C. Rawlinson, whose ability he directed to the study of oriental

literature. He had been Governor for little more than a year when he

first received, at his daily public breakfast at Parell, the young

Scottish missionary from his own loved Tweedside. Even better than his

predecessor, Malcolm knew how to influence the natives, by whom he was

worshipped. He continued the administrative system as he found it,

writing to a friend—“ The only difference between Mountstuart and me is

that I have Mullagatawny at tiffin, which comes of my experience at

Madras.” The Governor was in the thick of that collision with the

Supreme Court, forced on him by Sir John Peter Grant’s attempt to

exercise jurisdiction all over the Presidency—as in Sir Elijah Impey’s

days in Calcutta. He had just returned from one of those tours through

the native States, which the Governor, like Elpliinstone before him and

the missionary after him, considered “of primal importance ” for the

well-being of the people. The decision of the President of the Board of

Control at home, then Lord Ellenborough, was about to result in the

resignation of the impetuous judge. Such was Bombay, politically and

territorially, when, in the closing weeks of the cold season of 1828-9,

John Wilson and his wife landed from the “ Sesostris ” East Indiaman.1

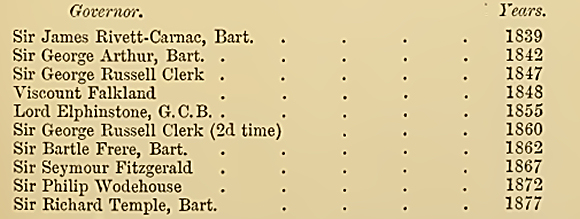

Our readers will find it useful to refer to this list of the Governors

of Bombay just before and during Dr. Wilson’s work there—

Governor. Years.

Jonathan Duncan . . . . . .1795

Sir Evan Nepean, Bart. . . . . . 1812

The Hon. Mountstuart Elphinstone . . . 1819

Sir John Malcolm, K.C.B. .... 1827

Earl of Clare......1831

Sir Robert Grant ...... 1835

Economically the year 1829 was marked by the first serious attempt on

the part of the Directors at home, and the Government on the spot, to

extend the cultivation and improve the fibre of the cotton of Western

India, which was to prove so important a factor alike in the prosperity

and the adversity of Bombay in the coming years. In that review of this

three years’ administration to 1st December 1830, which Sir John Malcolm

wrote for his successors, and published to influence the discussions on

the Charter of 1833, under the title of The Government of India, this

significant sentence occurs :—“ A cotton mill has been established in

Bengal with the object of underselling the printed goods and yarns sent

from England; but there are, in my opinion, causes which, for a long

period, must operate against the success of such an establishment.” The

period has not proved to be so long as the conservative experience of

the Governor led him to believe. In this respect Bombay soon shot ahead

of Bengal, which afterwards found a richer trade in jute and tea. But

the withdrawal of' the last restriction on trade was, when Wilson

landed, about to co-operate with a consolidated administration to make

Bombay the seat of an enriching commerce, of which its varied native

communities obtained a larger share than elsewhere. A society composed

of Hindoo, Parsee, Jewish, and even Muhammadan merchant princes, was

being brought to the birth, side by side with the great Scottish houses,

at the head of which was Sir Charles Forbes. And the man had / come to

lift them all to a higher level; to purify them all, in I differing

degrees, by the loftiest ideal.

Sir W. H. Macnaghten was

massacred in 1841 when about to leave Gabul to join his appointment as

Governor of Bombay. The Honourable Messrs. George Brown in 1811; John

Romer in 18-31 ; James Farish in 1838 ; G. W. Anderson in 1841; and L.

R. Reid in 1846, were senior members of council, who acted for a short

time as interim governors.

At this time our Indian Empire was just one third of its present

magnitude, but its native army was 186,000 strong, a fourth more than

since the Mutiny. Including St. Helena, the area was 514,238 square

miles, the population 89J millions, and the gross revenue £21,695,207.

The whole was administered in 88 counties by 1083 British civil

officers, and defended by 37,428 white troops. Of the three Presidencies

the Western was by far the smallest, but its geographical position gave

it an advantage as the centre of action from Cape Comorin to the head of

the Persian Gulf, and from Central India to Central Africa. Its area was

65,000 square miles, not much more than that of England and Wales. Its

population was 6j millions in ten counties, and its gross annual revenue

2J millions sterling. The whole province was garrisoned by 7728 white

troops and 32,508 sepoys, under its own Commander-in-Chief; and it had a

marine or navy, famous in its day and too rashly abolished long after,

which was manned by 542 Europeans and 618 natives.

Notwithstanding the enlightened action and tolerant encouragement of

Mountstuart Elphinstone and Malcolm, public instruction and Christian

education were still in the day of small things in Bombay, although it

was in some respects more advanced than Bengal, which soon distanced it

for a time. In the Presidency, as in Madras and Calcutta, a charity

school had been, in 1718, forced into existence by the very vices of the

English residents and the conditions of a then unhealthy climate.

Legitimate orphans and illegitimate children, white and coloured, had to

be cared for, and were fairly well trained by public benevolence, for

the Company gave no assistance till 1807. In the Charter of 1813, which

Charles Grant and Wilberforce had partially succeeded in making half as

liberal as that granted by William III. in 1698, Parliament gave India

not only its first Protestant bishop, archdeacons, and Presbyterian

chaplains, but a department of public instruction bound to spend at

least a lakh of rupees a year, or £10,000, on the improvement of

literature, and the promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the

people. In 1815 the Bombay Native Education Society was formed, and

opened schools in Bombay, Tanna, and Broach, with the aid of a

Government grant. Immediately after Mountstuart Elphinstone’s

appointment as Governor it extended its operations to supplying a

vernacular and school-book literature. It recommended the adoption of

the Lancasterian method of teaching, then popular in England, and it

continued its useful -work till 1810, when it became in name, what it

had always been in fact, the public Board of Education. Since it failed

to provide for the Southern Konkan, or coast districts, Colonel Jervis,

R.E., who became an earnest coadjutor of Wilson, established a similar

society for that purpose in 1823, but that was affiliated with the

original body. When Poona became British, Mr. Chaplin, the Commissioner

in the Dekhan, established a Sanskrit college there, which failed from

the vicious Oriental system on which it was conducted, in spite of its

enjoyment of the Dukshina, or charity fund of Rs. 35,000 a year, which

the Peshwas had established for the Brahmans’ education. The Society’s

central school in Bombay was more successful, and is still the principal

Government High School. When Mountstuart Elphinstone left Bombay in

1827, the native gentlemen subscribed, as a memorial of him, £21,600,

from the interest of which professorships were to be established “ to be

held by gentlemen from Great Britain, until the happy period arrived

when natives shall be fully competent to hold them.” But no such

professors landed till 1835, when they held, in the Town Hall, classes

which have since grown into the Elphinstone College. In that year, out

of a population of more than a quarter of a million in the Island of

Bombay only 1026 were at school; in the rest of the province the

scholars numbered 1864 in the Maratha, and 2128 in the Goojaratee

speaking districts, or 5018 in all. In the four years ending 1830, just

before and after Wilson’s arrival, the Bombay Government remarked, “with

alarm,” that although it had fixed its annual grant to public

instruction at £2000 it had spent £20,192 in that period. So apathetic

were the natives that they had subscribed only £471, while the few

Europeans 1 had given £818 for the same purpose. Truly the system of a

vicious Orientalism was breaking down, as opposed to that of which

Wilson was to prove the apostle—the communication of Western truth on

Western methods through the Oriental tongues so as to elevate learned

and native alike. The almost exclusively Orientalising policy of the

Government previous to 1835, left Bombay a tabula rasa on which

Wilson soon learned to engrave characters of light and life that were

never to be obliterated.

Nor had the few missionaries then in Western India anticipated him.

Self-sacrificing to an extent for which, save from their great

successor, they have rarely got credit, they were lost in the jungle of

circumstances. The American missionaries were the first Protestants to

take up the work which, in the early Christian centuries, the Nestorians

had begun at the ancient port of Kalliana, the neighbouring Callian,

which was long the seat of a Persian bishop. In 1813, Dr. Coke sailed

for Bombay with the same Colonel Jervis, RE., who did so much for the

Konkan. His successors, for he died at sea, began that work of primary

importance in every mission, an improved edition of the New Testament in

the vernacular Marathee, for which Mr. Wilson expressed his gratitude

soon after his arrival. But when, at a later period, one of their annual

reports ignorantly represented the Americans as having been the first to

evangelise the Marathas, he felt constrained to publish this statement

of the facts.

The American missionaries first came to Bombay in 1813; but the whole of

the New Testament in Marathee had been published by the Serampore

missionaries in 1811. Dr. Robert Drummond published his grammar and

glossary of the Goojaratee and Marathee languages at the Bombay Courier

press in 1808. Dr. Carey published his Marathee grammar and dictionary

at Serampore in 1810. All these helps were enjoyed by the American

missionaries; and though they are by no means so important as those

which are now accessible to all students and missionaries, we would be

guilty of ingratitude to those who furnished them were we to overlook

them. Suum cuique tribue should ever be our motto. The Romish Church we

know to be very corrupted; but. I have seen works composed by its

missionaries about two hundred years ago, which could ‘ give the

Marathas the least idea of the true character of God as revealed in the

Scripture/ It is too much when the labours of the Romish missionaries

are considered, to affirm that ‘not a tree in this forest had been

felled’ till the American missionaries came to this country. There have

been some pious Roman Catholics in Europe, and why may there not have

been some amongst the eight generations of the 300,000 in the Marathee

country? The Serampore missionaries admitted several Marathas to their

communion before 1813.”

The first American missionaries had their own romance, like all

pioneers. They were driven from Calcutta by the Government in 1812, and

told they might settle in Mauritius. Judson happily was sent to Burma by

Dr. Carey. Messrs. Hall and Nott took ship to Bombay. Thence the good

but weak Sir Evan Nepean, who had been shocked by Elphinstone’s firmness

in the Poona plot, warned them off; but an appeal to his Christian

principle led him to temporise until Charles Grant and the charter of

the next year restrained the Company. In 1815 the London Missionary

Society repeated at Surat, and afterwards in Belgaum, an effort to found

a mission, which in 1807 had failed in the island of Bombay. In 1820,

the Church Missionary Society began in Western India that work which in

time bore good fruit for Africa also. In 1822 the increase of British

territory, caused by the extinction of the Maratha power, led the

Scottish Missionary Society, which since 1796 had been working in West

Africa, to send as its first missionary to Bombay the Kev. Donald /

Mitchell, a son of the manse, who, when a lieutenant of in-1 fantry at

Surat, had been led to enter the Church of Scotland. He was followed by

the Revs. John Cooper; James Mitchell; Alexander Crawford, whose health

soon failed; John Stevenson, who became a chaplain; and, finally, Robert

Nesbit, fellow student of Dr. Duff at St. Andrews University under

Chalmers, and Wilson’s early friend. “Desperately afraid of offending

the Brahmans,” as a high official expressed it, the authorities would

not allow the early Scottish missionaries to settle in Poona, which had

too recently become British, as they desired. Had not a native

distributor of American tracts just before been seized, by order, and

escorted to the low land at the foot of the Ghauts'? So there, on the

fertile strip of jungly coast, in the very heart of the widow-burning,

self-righteous, intellectually able and proud Maratha Brahmans, the

Scottish evangelists began their work, of sheer necessity, for they

considered that Bombay was already cared for by the American and English

missions. The Governors, Elphinstone and Malcolm, however, although they

would not allow the good men to be martyred in Poona, as they supposed,

with all the possible political complications, subscribed liberally to

their funds, a thing which no Governor-General dared do till forty years

after, when John Lawrence ruled from Calcutta. In Hurnee and Bankote,

from sixty to eighty miles down the coast from Bombay, these

missionaries had preached in Marathee and opened or inspected primary

schools, with small results. So terrible was the social sacrifice

involved in the profession and communion of Christianity, that the first

Hindoo convert, in 1823, some weeks after his baptism, rushed from the

Lord’s Table when Mr. Hall was about to break the bread, exclaiming,

“No, I will not break caste yet.” Long before this the good James

Forbes, father of the Countess de Montalembert, had given it as his

experience of Anglo-Indians at all the settlements of Bombay, from

Ahmedabad to Anjengo, and dating from 1766, “ that the character of the

English in India is an honour to the country. In private life they are

generous, kind, and hospitable; in their public situations, when called

forth to arduous enterprise, they conduct themselves with skill and

magnanimity; and, whether presiding at the helm of the political and

commercial department, or spreading the glory of the British arms, with

courage, moderation, and clemency, the annals of Hindostan will transmit

to future ages names dear to fame and deserving the applause of Europe.

. . . With all the milder virtues belonging to their sex, my amiable

countrywomen are entitled to their full share of applause. This is no

fulsome panegyric ; it is a tribute of truth and affection to those

worthy characters with whom I so long associated, and will be confirmed

by all who resided in India.”1 Mr. Forbes finally left India in 1784,

when only thirty-five years of age, but after eighteen years’

experience.

The successive Governors had given an improved tone to Anglo-Indian

society, and the few missionaries and chaplains had drawn around them

some of the officials both in the Council and in the ordinary ranks of

the civil and military services. But the squabbles in the Supreme Court,

and the reminiscences of a Journalist,2 who has published his memoirs

recently, show that here also the new missionary had a field prepared

for him, which it became his special privilege to develop and adorn with

all the purity of a Christian ideal and all the grace of a cultured

gentleman. What in this way he did, unobtrusively and almost

unconsciously, in Bombay * for forty years, will hardly be understood

without a glance at this picture of Bombay in 1830, as drawn by the

editor of the Bombay Courier:—

“The opportunity of leaving Bombay was not to be regretted. ‘ Society’

on that pretty little island had a very good opinion of itself, but it

was in reality a very tame affair. It chiefly consisted of foolish burra

sahibs (great folks) who gave dinners, and chota sahibs (little folk)

who ate them. The dinners were in execrable taste, considering the

climate. . . . But the food for the palate was scarcely so flavourless

as the conversation. Nothing could be more vapid than the talk of the

guests, excepting when some piece of scandal affecting a lady’s

reputation or a gentleman's otticial integrity gave momentary piquancy

to the dialogue. Dancing could hardly be enjoyed with the thermometer

perpetually ranging between S0° to 100° Fahrenheit, and only one

spinster to six married women available for the big-wigs who were yet to

be caged. A quiet tiffin with a barrister or two, or an officer of the

Royal Staff who could converse 011 English affairs, with a game of

billiards at the old hotel or one of the regimental messes, were about

the only resources, next to one’s books, available to men at the

Presidency endowed with a trifling share of scholarship and the thinking

faculty.”

Such was Bombay, the city and the province, when John Wilson thus wrote

to the household at Lauder his first impressions of the

former:—“Everything in the appearance of Bombaj” and the character of

the people differs from what is seen at home. Figure to yourselves a

clear sky, a burning sun, a parched soil, gigantic shrubs, numerous palm

trees, a populous city with inhabitants belonging to every country under

heaven, crowded and dirty streets, thousands of Hindoos, Muhammadans,

Parsees, Buddhists, Jews, and Portuguese; perpetual marriage

processions, barbarous music, etc. etc.; and you will have some idea of

what I observe at present. In Bombay there are many heathen temples,

Muhammadan mosques, and Jewish synagogues, several Roman Catholic

chapels, one Presbyterian Church, one Episcopal Church, and one Mission

Church belonging to the Americans. I preached in the Scotch Church on

the first Sabbath after my arrival, and in the Mission Church on Sabbath

last.” |