|

Few of the many ecclesiastical ruins on Iona to-day are older

than the early thirteenth century. The cursory visitor will probably limit

his attention to the mediaeval ruins, which include the Cathedral—the most

distinguished and interesting of the remains—the Monastery, the Nunnery, and

St. Oran’s Chapel; the ancient burial-ground of Reilig Orain; and the

Crosses and sculptured stones. For those with leisure and interest there is

much else.

Maclean’s Cross. On the road from the village to the

Cathedral, on the spot, it is said, where Columba rested half-way on the

last day of his life, there stands a mediaeval, way-side cross, carved from

a thin slab of schist, ten feet high above its pedestal. On its western

side, the central figure is a crucified Christ in a long robe; a

fleur-de-lis is above, and a chalice is on one side. The shaft is ornamented

with foliage and the interlacing that is characteristic of Celtic ornament.

The east side has an ornamental pattern, and below are two animals and a

mounted knight with helmet and lance. The cross is believed to be fifteenth

century work, and probably commemorates a Maclean of Duart — that branch of

the clan in whose country Iona lay.

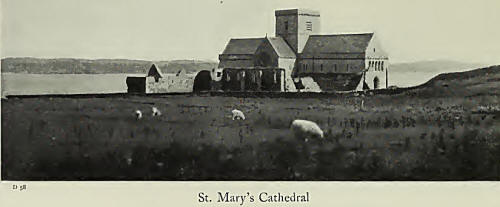

The Cathedral, which is dedicated to the Virgin Mother, has

been recently restored. It is a cruciform building, measuring 148 feet 7

inches from east to west, and 70 feet 3 inches from north to south, with a

massive square tower 70 feet high.

The architecture.is Norman, of Continental design; for in

architecture, as in other matters, “owing probably to the Celtic element in

the population”, says Ferguson, “the affinities and predilictions of the

Scotch were for Continental nations, and especially for France”. The same

authority points out that “ the circular pier-arch is used with the

mouldings of the thirteenth century, and the pointed arch is placed on a

capital of intertwined dragons, more worthy of a Runic cross or tombstone

than a Gothic edifice. The tower windows are filled with quatrefoil tracery,

in a manner very unusual, and a mode of construction adopted which does not

perhaps exist anywhere else in Britain.”

Other details of interest within the building are the

capitals of the tower piers and of the pillars, which are carved with a

curious medley of subjects: foliage, grotesque monsters, groups of men and

beasts, and Biblical subjects; the carved Gothic sedilia; the tombs of two

fifteenth-century abbots of Iona, John Mackinnon and Kenneth Mackenzie,

north and south of the sanctuary; a stone with an incised Celtic cross,

which, according to tradition, was St. Columba’s pillow and later his

gravestone (for Adamnan says they set up his stone pillow as a monument at

his grave), and some sculptured stones brought in from Reilig Orain for

their better preservation. There is also a modern tomb—that of a Duke of

Argyll.

Columba’s Tomb. On the north side of the entrance to the

Cathedral nave, there is a small and very ancient oratory, the east end of

which is formed by the cloister wall. It contains two stone cists, of which

the greater, on the south side, traditionally held the shrine of Columba,

and the lesser, that on the north, possibly that of his faithful attendant

Diormit, or, as some think, of St. Blathmac, who was killed in the Danish

raid of 825.

From the time of the first Danish raids on Iona, the shrine

was freely translated between Ireland and Scotland (including Dunkeld), and

was lost sight of before the Benedictine settlement.

St. Martin’s Cross. A few

yards from Columba’s tomb, and directly facing it, stands the great Cross of

Iona, dedicated to St. Martin of Tours, a friend of St. Ninian and

contemporary of St. Patrick, and one of the most outstanding figures of the

fourth century. The cross, now hoary with years, is of massive schist on a

granite pedestal. On the east side it is decorated with bosses and serpents;

on the west, the central subject is a Virgin and Child surrounded by four

angels, and on the arms and shafts are animals and groups of human figures,

portraying scriptural subjects, with bosses and serpents below. The cross is

of the Celtic period, probably tenth century, and alone of its

contemporaries has weathered the ages. The broken shafts of two possibly

earlier crosses—St. John’s and, to the south, St. Matthew’s—stand between

St. Martin’s Cross and the oratory.

The Black Stones of Iona. Near St. Columba’s Tomb there stood

formerly one of the most ancient and sacred of Iona’s relics—the Black

Stones of Iona, so called, not from their colour, but from the black doom

that fell on any who dared to violate an oath sworn upon them. So recently

as the reign of James VI and I, two clans who had spent centuries in bloody

feud met here and solemnly pledged themselves to friendship. The last of

these stones disappeared about a century ago.

There is a tradition that the Coronation Stone in Westminster

Abbey was originally one of the famous Black Stones. Its legendary history

is very ancient, for it is believed to have been reverenced as Jacob’s

pillow by the tribes who brought it from the East in the first wave of

Celtic emigration. “On this stone—the old Druidic Stone of Destiny, sacred

among the Gael before Christ was born—Columba crowned Aidan King of Argyll.

Later the stone was taken to Dunstaffnage, where the Lords of the Isles were

made princes: thence to Scone, where the last of the Celtic Kings of

Scotland was crowned on it. It now lies in Westminster Abbey, a part of the

Coronation Chair, and since Edward I every British monarch has been crowned

upon it. If ever the Stone of Destiny be moved again, that writing on the

wall will be the signature of a falling dynasty.”—(Fiona Macleod.)

Skene questions all its history before its use for Scottish

coronations at Scone.

The Monastery. The ruins of the Benedictine monastery founded

by Reginald, Lord of the Isles, in the beginning of the thirteenth century,

adjoin the Cathedral on the north. There is a square cloister, which has the

Cathedral nave on the south, the chapterhouse on the east, and the refectory

on the north. A room above the chapter-house is believed to have housed the

famous Library of Iona. The kitchen stands a little apart, north of the

refectory. A kitchen midden, containing bones, shells, and other refuse, was

discovered between the two buildings a few years ago.

Traces of Celtic Monastery. The first simple, monastic

buildings in Iona were erected by Columba, thirteen hundred years ago, and

probably several buildings have arisen and decayed between that date and the

foundation of the last Celtic monastery. We know that the wooden buildings

burned by, the Danes in 802 were succeeded by a building of stone, but it is

hardly likely that the present remains are those of the first, or even the

second, stone monastery.

The Celtic monastery consisted ordinarily of a group of small

stone churches of simple design and peculiar orientation, dominated by a

round tower which served as belfry, lookout station, and place of refuge.

Services were held in the little churches simultaneously; or sometimes

successively, so that a continuous round of praise was kept up, day and

night.

The traces of such a monastery in Iona include a small,

roofless church, 33 feet by 16, north-east of the Cathedral enclosure; the

foundation of a round tower (discovered in 1908); the traces of what seem to

have been cells; and the remains of an outer wall of a range of buildings

west of the cloister. “There seems to have been a central community house,

having, on the east, the small church and other detached buildings, whose

remains are visible, and, on the west, the round tower and high crosses

contiguous to the little oratory of the shrine. There were outlying chapels

also, for St. Mary’s, St. Oran’s, St. Kenneth’s, St. Ronan’s, and Cladh an

Diseart are Celtic sites.” —(Trenholme.)

The Nunnery. Like the Monastery, the Nunnery was established

at the beginning of the thirteenth century by Reginald, Lord of the Isles,

whose sister Bethog, or Beatrice, was the first Abbess of Icolmkill. The

early nuns were Benedictines; later—the date and the reason are unknown—they

changed to the Augustine order.

The architecture is Norman, of a type commonly used prior to

the twelfth century. The apartments grouped around the enclosure include a

chapter-house with stone seats, a chapel with an aisle on the north side, a

refectory, and a kitchen. The spaces between the arches have been filled up

with solid masonry, possibly with a view to preventing cattle from straying

into the building. There are several sculptured tombstones within the walls,

the most notable being that of the Prioress Anna (ob. 1543)—an effigy in low

relief—and the beautiful Nunnery Cross.

Sacheverell, who visited Iona in 1688, tells us that the

Nunnery chapel was the burial-place of all the ladies in that part of

Scotland, as St. Oran’s was of the men of rank and distinction; and it

continued so till the end of the eighteenth century.

On the north side of the Nunnery stand the ruins of St.

Ronan’s Church, which appears to have been the parish church before the

Reformation.

Reilig Orain. The ancient burying-ground of Reilig Orain

lies, “weel biggit about with staine and lyme” (Munro), a little southwest

of the Cathedral. The name signifies the burial-place of Oran. According to

a tale in the Old Irish Life of Columba, it was revealed to the saint that a

human sacrifice would be necessary for the success of his mission. His

brother Oran, one of the twelve brethren who accompanied him to Iona,

offered himself, and was buried alive. On the third day, Columba caused the

grave to be opened, whereupon Oran opened his eyes, and said: “Death is no

wonder, nor is hell as it is said.” Such heresy was not pleasing to the

saint’s ear, and his reply, “Earth, earth on Oran’s eye, lest he further

blab”, has passed into a proverb.

This story is not mentioned by Adamnan, nor is the name Oran

to be found in the list of Columba’s twelve companions. The name may have

been derived from one Oran, whose death is recorded fifteen years before the

landing of Columba, or from a monk of the same name, whose burial may have

been the first in the community. Reilig Orain was probably the original

burial-place of the Family of Hy, for Columba is believed to have been

buried here (though his remains were enshrined at a later period, and placed

in the little oratory, as afore described), and, on this account, Reilig

Orain became a famous sanctuary for fugitives.

Within this “awful ground”, as Dr. Johnson describes it, lie

the surviving gravestones of the dead of thirteen centuries. When Iona was

at the zenith of her fame and had become a holy place in all the land, the

bodies of princes, chiefs, and ecclesiastics throughout Celtic Scotland and

beyond it were brought here for burial. An ancient prophecy may have

increased the desire for interment in Iona:—

“Seven years before the judgment,

The sea shall sweep over Erin at one tide,

And over blue-green Isla;

But I of Colum of the Church shall swim."

Records of royal burials are found in the old Chronicle of

the Picts and Scots, from Adamnan’s time onwards. Kenneth Mac-alpine, the

first king of a united Scotland, was buried here in 860, and the precedent

was followed by most of the kings after him for two centuries. Shakespeare’s

lines may be recalled:

Rosse. Where is Duncan’s body?

Macduff. Carried to Columskill,

The sacred storehouse of his predecessors,

And guardian of their bones.

Macbeth, too, was laid to rest here, beside his reputed

victim.

Duncan’s son, Malcolm Canmore, was the first to break the

tradition of Royal burials in Iona; his body lies in Dunfermline.

The remains of sixty kings in all are believed to lie “eirded

in this very fair kirkyaird”. Monro, Dean of the Isles, who visited the

island in 1549, describes three tombs, resembling small chapels, and bearing

the legends “Tumulus Regum Scotiae“ "Tumulus Regum Hiberniae”, and “Tumulus

Regum Norwegiae”, respectively. Here were interred forty-eight crowned kings

of Scotland, four of Ireland, and seven of Norway. When Pennant visited the

island in 1772, the tombs were in ruins, and the inscriptions lost.

Most of the older tombstones have been gathered together in

two parallel rows, near the middle of the enclosure. The Ridge of the Kings

lies to the west; the Ridge of the Chiefs to the east.

The Ridge of the Kings contains twenty-one stones, which are

unnamed, save the following, numbered from left to right:—

3. Bishop Aodh Cama-chasach (Hugh of the Crooked Legs).

12. Reginald, Lord of the Isles {ob. 1207), founder of the

Benedictine Monastery and Nunnery on Iona.

The Ridge of the Chiefs, called also the Ridge of the

Macleans, contains nineteen stones, of which again many are nameless.

4. A Macleod of Lewis {ob. circa 1532).

5. Called “The Rider”, from the figure of a mounted knight

with spear at charge, at the top of the stone. A fourteenth-century Maclean.

8. A Maclean, known as Ailean nam Sop (Allan of the Straw), a

noted pirate and freebooter in his youth, whose by-name is derived from the

combustible with which he freely set fire to houses during his raids.

14. “The Four Priors.” A stone with four panels,

commemorating four Iona ecclesiastics of the fifteenth century.

15. Maclean of Lochbuie (circa 1500).

16. Maclean of Coll.

17. Another Maclean of Lochbuie, Eoghan a’ Chinn Bhig (Ewan

of the Little Head), who was killed in a fierce clan fight about 1538. “It

was a common belief in the olden time that this personage always appeared

when a member of his family was about to die. A little over fifty years ago,

a native of the island declared that he saw loin pass him at Maclean’s Cross

on his black horse, with his little head under his arm.”—(Macmillan).

19. Dr. John Beton (ob. 1657). According to Skene, the Betons,

or Macbeths, were hereditary physicians in Isla and Mull, and also

sennachies (historians) of the Macleans.

On the eastern side of the Ridge of the Kings there lies a

rough block of red granite, bearing an incised cross, and believed to mark

the grave of a nameless king of France.

Near the western wall of the graveyard there is a stone

erected by the Government of the United States to the memory of sixteen

persons who went down with the American ship Guy Mannering, off the west

coast of Iona,, on New Year’s Eve, 1865.

St. Oran’s Chapel. Within Reilig Orain is a small, roofless

chapel, 29 feet by 15 in dimension and dedicated to St. Oran. It is the

oldest of the mediaeval ruins, and is believed to have been erected by the

pious Margaret, the Saxon queen of Malcolm Can-more, in the eleventh

century. The doorway has a richly carved Norman arch of later date than the

chapel itself, and a mediaeval altar-tomb, surmounted by a triple arch, has

been built into the southern wall. Some carved stones are sheltered within

the chapel.

Clach Brath. Near the edge of the path leading to St. Oran’s

Chapel, there lies a broad, flat stone, with a slit and cavity on its

surface. Here there used to lie some small, round stones which pilgrims were

wont to turn sunwise within the cavity; for it was commonly believed that

the “ brath ”, or end of the world, would not arrive until this stone should

be worn through.

The Sculptured Stones. One of the many names of antiquity by

which Iona has been called is Innis nan Druineach, the Island of Cunning

Workmen, or, more freely translated, of the Sculptors. Iona was a centre not

only of Celtic religion and Celtic learning but also of Celtic art. The

Celtic race in these islands achieved nothing—indeed attempted nothing—in

the higher planes of sculpture or painting; for these were the Dark Ages,

when Greece had passed into obscurity, and the

Renaissance was yet to come. The artistic genius of the Gael

was confined to decorative art, but within that domain reached a rare degree

of excellence.

[The Celtic races have been

necessarily almost impotent in the higher branches of the plastic arts. . .

. The abstract, severe character of the Druidical religion, its dealing with

the eye of the mind rather than the eye of the body, its having no elaborate

temples and beautiful idols, all point this way from the first; its

sentiments cannot satisfy itself, cannot even find a resting-place for

itself in colour and form ; it presses on to the impalpable, the ideal. The

forest of trees and the forest of rocks, not hewn timber and carved stones,

suit its aspirations for something not to be bounded or expressed. . . .

Ireland, that has produced so many powerful spirits, has produced no great

sculptors or painters (Matthew Arnold : Study of Celtic Literature).]

Celtic art in Scotland is almost entirely Christian. In the

early days, parchment was the sole medium of expression, and the monks of

Iona were devoted to the copying of manuscripts. Columba, as we know, was a

skilled scribe, and so was Baithne, his cousin and successor. There still

survive some priceless examples of this “abstract and unemotional art”, such

as the Book of Kells, an eighth-century Iona manuscript (now in Dublin)

which is unrivalled in its sensitive beauty of line and colour. When, at a

later date, stone came into use, there were shown the same qualities that

characterize the illuminated work —purity, delicacy, and exquisite

workmanship.

The sculptured stones are distributed variously. Some are

sheltered within the Cathedral, and some—including St. Martin’s Cross and

one or two broken cross-shafts — are in the Cathedral precincts. Others are

in Reilig Orain—in the Ridges of the Kings and Chiefs —and in St. Oran’s

Chapel. The women’s memorial stones are gathered within the Nunnery.

Maclean’s Cross stands apart, on the roadside, not far from the Nunnery

ruins.

Two distinct periods are represented in the workmanship of

the stones: the earlier are of the pure Celtic type, while the later, or

mediaeval ones, show alien influences. The latter naturally predominate.

There are roughly three types of stone:—

The first category includes a few unshaped boulders, with

incised crosses, all probably of early date. The most celebrated is the

traditional pillow of Columba, now preserved in the Cathedral.

Secondly, there are numerous grave-slabs. The flat stones,

with crosses incised or in relief, belong to the Celtic period. A few are

probably early specimens, but those bearing inscriptions are considered from

the style of lettering to belong to near the end of the Celtic Church

period. The Irish Cross (St. Oran’s Chapel) and the Nunnery Cross (Nunnery)

are two fine specimens of this period.

The flat slabs of the mediaeval period are more ornate than

the earlier ones. Foliage decoration is used, and sometimes the figures of

animals. Many bear emblems, such as the warrior’s claymore, the abbot’s

crozier, the chief’s galley (that of each island clan was distinctive), the

Cross, or the triquetra (Celtic emblem of the Trinity). On the women’s

stones such emblems as shears, mirrors, and combs appear.

The gravestones include also some recumbent effigies, all

mediaeval work.

Thirdly, there are the high standing crosses of both Celtic

and mediaeval periods. These crosses are believed to have been numerous at

one time: there is a tradition, indeed, though it is far from reliable, that

no less than three hundred and fifty of them were flung into the sea at the

time of the Reformation.

The Celtic Cross is distinguished from all others by its

form, which combines two symbols, the ring and the cross, the ring

intersecting the arms and shaft of the cross. The decorative treatment is

also distinctive, and it is noteworthy that in the two hundred and fifty

crosses of the Irish Church, no crucifixion is found.

Only two crosses remain intact in Iona: the splendid St.

Martin’s, already described, which is of the purest Celtic type; and

Maclean’s, which, though Celtic in form, is stamped mediaeval by its foliage

decoration and its central figure of Christ crucified. |