|

SUGAR is so extensively used

among all classes of society, that it is regarded as almost a necessary. In

point of commercial importance it ranks very high, and the duty drawn from

it forms a considerable item in the national revenue. Yet, up till what must

be considered a recent period, in speaking of what is a common article of

food, sugar was mentioned only as a medicine, and subsequently as a luxury,

to which the wealthy alone could aspire. The first reference to sugar occurs

in the works of Theophrastus, who lived 320 years before the Christian era,

where it is called "a sort of honey extracted from canes or reeds."

Subsequent writers among the ancients refer to sugar as an object of

curiosity, and Pliny expressly states that it was used in medicine only. The

Chinese were acquainted from a remote period with the process of making

sugar- candy, and the Greeks and Romans obtained the little that came under

their notice from China. It would appear that Europe is indebted to the

Saracens not only for the first considerable supplies of sugar, but for the

earliest example of its manufacture. After conquering the islands of Rhodes,

Cyprus, Sicily, and Crete in the ninth century, the Saracens introduced into

them the sugarcane; and from that source Europeans drew their first

supplies. The same people began the cultivation of the sugar-cane in Spain

as soon as they obtained a footing in it. About 1420 the Portuguese took the

sugar-cane from Sicily to Madeira and the Canary Islands; and from these

places the cultivation of the cane and the art of making sugar were extended

to the West Indian Islands and the Brazils. The first British settlement in

the West Indies was Barbadoes, which was taken possession of in 1627. Twenty

years afterwards sugar began to be exported from the island, and that was

the first sugar produced in British possessions, the supply previously being

obtained chiefly from the Portuguese settlements in Brazil. The British

planters in Barbadoes, after becoming thoroughly acquainted with the modes

of cultivating and extracting the sugar, did a large trade, and thereby

accumulated much wealth. In 1676 they employed in their sugar trade a fleet

of four hundred vessels. The first mention of sugar being imported into

England is found in Marin's "History of the Commerce of Venice," which

refers to a shipment at Venice for England in the year 1319 of about forty

tons of sugar and four tons of sugar-candy. In those early days honey was

the principal ingredient used in sweetening liquors and dishes; and for many

years after sugar had been introduced, it was used only in the houses of the

wealthy. Not till the latter part of the seventeenth century, when coffee

and tea began to be consumed, did sugar come into general use.

For upwards of two centuries

sugar has been subject to an import duty. In 1661, when it was first levied,

the duty amounted to ls. 6d. per cwt. on all sugar brought from British

plantations. Eight years afterwards it was raised to 3s. By a series of

augmentations the duty rose to 30s. per cwt. in 1806. From 1793 to 1803 the

duty on East India sugar was 37 and 38 per cent. ad valorem, and for many

years afterwards it was 11s. and 8s. per cwt. higher than the duty on West

India sugar. The rates of duty were assimilated in 1836 by the reduction of

the charge on East India sugar from 32s. to 24s. per cwt. A prohibitory duty

of 60s. to 63s. per cwt. was imposed on foreign sugars up till 1844, when it

was, under certain circumstances, lowered to 34s.; and in some favoured

instances (to encourage free instead of slave labour) the charge was fixed

as low as 23s. 6d. Sugar from British possessions was at that time paying

from 14s. to 21s., according to quality. By Acts passed in 1816 and 1848,

the duties on British and foreign sugar were gradually equalised. The

equalisation was completed in 1854, in which year all sugars paid from 10s.

to 13s. 4d., according to quality. Those rates were increased during the

Russian war, and, by the tariff of 1860, another advance was made to from

12s. 8d. to 18s. 4d. In 1867 the duty was lowered to from 8s. to 12s. per

cwt.

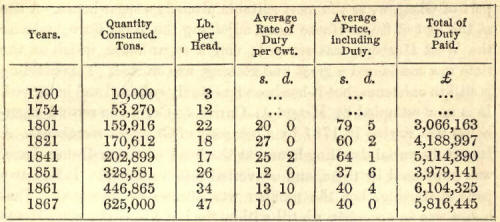

The quantity of sugar

consumed in Britain in the year 1700 was only 10,000 tons, while in 1868 it

was nearly 700,000 tons. The following table, though not quite perfect,

shows correctly enough for general readers the quantity consumed in various

years, the number of pounds per head of the population, the price per cwt.

including duty, and the amount of duty paid on all descriptions of sugar:—

It is estimated that the

annual production of sugar over the world amounts to 3,000,000 tons. Roughly

dividing the nations into groups, the interesting fact is shown that the

Anglo-Saxon races— Great Britain and her colonies and the United States—are

the most important consumers, as they use 1,142,000 tons of sugar per annum,

or 41.40 lb per head. The .Latin races come next. France, Italy, Spain,

Belgium, Portugal, and Switzerland use 506,000 tons per annum, or 1214 lb.

per head. The Zollverein, Austria, Holland, the Hanseatic League, and

Denmark, consume 262,000 tons per annum, or 7.30 lb. per head. Last come the

vast but poverty- stricken districts ruled by Russia, together with the

semi-barbarous Ottoman Empire, and the kingdom of Greece. Russia, Poland,

Turkey, and Greece consume less than half of what is used by the smallest

civilised European consumers, and the deliveries in these countries amount

to only 125,000 tons, or 3.30 lb. per head.

In Stow's "Survey of London,"

it is stated that the art of refilling sugar was commenced in that city

about the year 1544, by the erec¬tion of two refineries. After twenty years

of varied fortune, those refineries turned out to be very remunerative to

their owners, and many other persons embarked in the business. For a

considerable time the London refineries enjoyed a monopoly of the trade,

which was subsequently shared with Liverpool and Bristol. Scotland was long

behind the sister kingdom in engaging in sugar-refining; but now the Scotch

refiners are rivalling those of England, and have, during the past ten

years, made marvellous progress. There are in Scotland twenty sugar

refineries—fourteen at Greenock, three at Glasgow, two at Leith, and one at

Port-Glasgow; but several of these, owing to various causes, are not in

operation at present.

The first sugar-refinery in

Greenock was started in 1765 by a few West Indian merchants, who formed

themselves into a company for that purpose. They fixed upon Greenock, which

at that time was the port of Glasgow, as the most suitable place for a

sugar-house. A site at the foot of Sugar-House Lane, adjoining the West

Burn, and near the West Harbour, was secured; and a sugar-house, which at

the time was considered a great undertaking, was erected. This building is

still in existence, but it has been repeatedly enlarged and improved. It is

now occupied by Messrs A. Currie & Co. The second sugar- house was started

in 1787 by a company of Greenock merchants. A large substantial

dwelling-house, at the head of Sugar-House Lane, was purchased by them, and

converted into a refinery. It had two pans at starting, but the number was

afterwards increased. That house was in operation up till within the last

five years, when it was sold and converted into a store. A third sugar-house

was built in 1802, in Bogle Street, by Messrs Robert Macfie & Sons, the

founders of extensive refineries in Liverpool and Leith. It contained two

pans at starting, but a third was added eight years afterwards; and it was

then considered an extensive concern. This refinery has been in the market

for some time, and a part of it was recently let as a store.

The fourth sugar-house was

built by Messrs James Fairrie & Co., on Cartsburn, in 1809. It was burned

many years ago, but another house was built farther up the burn, and is now

occupied by a young firm. The fifth sugar-house was built in 1812, by Messrs

Wm. Leitch & Co., in the Glebe. This house is not now a refinery, but the

name has been adopted by the Glebe Sugar-Refinery Company, now the most

extensive refiners in Greenock. It thus appears that in the forty-seven

years up till 1812, five sugar-houses had been erected in Greenock, the

third, fourth, and fifth having been built within a period of ten years. For

the next fourteen years there was a lull, and it was not till 1826 that the

sixth house was built, on a site at the High Bridge. Three years later

Messrs Tasker built a refinery in Dallingburn Street, which is carried on by

Messrs Crawhalls & Co. From 1830 till 1860, refineries were built for or

leased by the following firms :—Messrs Pattens; Walkers & Co.; Richard- sons

& Co.; Anderson, Orr, & Co.; A. Anderson & Co.; Blair, Reid, & Steele; Neill

& Dempster; Alexander Scott & Co.; and Ballantyne, Adam, & Rowan. The houses

of the two last named firms were built about eleven years ago. During the

past ten years only one new house has been built—namely, the Orchards

Sugar-Refinery, erected in 1863; but two or three of the old ones have been

rebuilt, and two of the houses mentioned are being rebuilt—one of them on a

new site. Of the Greenock refineries ten are in operation, two closed

temporarily, and two are being rebuilt. The most extensive works are those

of the Glebe Sugar-Refining Company, and of Messrs Walker & Company. Each of

these, it is said, turns out about 700 tons of sugar a-week. The Glebe

Sugar-Refining Company paid, in 1868, to the Customs, as duty on the sugar

refined in their establishment, L.350,000. They employ about 300 hands.

At Glasgow there are three

refineries. Two are at present working, and one has been stopped, owing to

action taken by the creditors of the concern. A sugar-house which was

carried on for many years in Port-Glasgow has been sold, and the proprietors

have in contemplation a large extension of their refinery in Greenock.

The great improvements made

in the machinery used in the refining process have, in the course of ten

years, and without any addition to the number of refineries in operation,

increased threefold the quantity of sugar refined—the raw sugar consumed by

all the refineries on the Clyde in 1858 being 56,769 tons—in 1868 it rose to

171,643 tons. The average quantity of refined sugar turned out by the

refineries in Greenock is about 60 tons a-day, when working full time, so

that the fourteen refineries are equal to the production of 840 tons a-day.

The amount of shipping employed in the sugar trade is very large. Last year

there arrived in the Clyde 416 vessels, of about 140,000 tons, or an average

of 335 tons. About 400 of these discharged their cargoes at Greenock. With

the exception of 16 vessels from Mauritius, 2 from Java, and 30 from Dunkirk

and Antwerp, the cargoes were from the West Indies and Brazils, 184 vessels

being from Cuba alone.

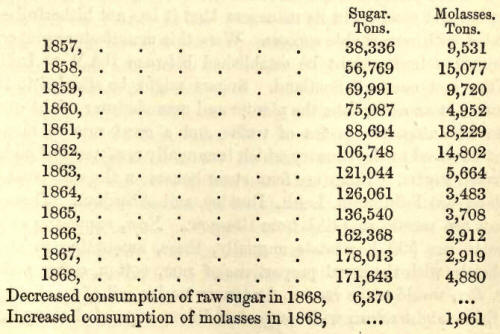

The following statement of

the imports into the Clyde during the past twelve years will show the

progress of the trade:-

It is evident, from recent

articles in trade newspapers, that the London refiners are finding those on

the Clyde to be very formidable competitors. Everywhere the Clyde sugars are

preferred by consumers, as being superior in quality to, and quite as cheap

as, those of London. The spirit of enterprise which has made the banks of

the Clyde famous in the annals of commerce and manufactures has been more

manifest in nothing than in the manner in which the trade of sugar-refining

has been taken up and is now carried on. Every promising invention tending

to perfect and expedite the processes is taken advantage of, and the Clyde

refiners are in all respects the best in existence. The London refiners

would appear to have felt secure in the monopoly which they long enjoyed of

supplying sugar to the millions of consumers in the metropolis, and they

have in most cases neglected to keep up to the march of improvement. Old and

costly processes are retained, and the produce is losing caste in the

markets where it comes into competition with Clyde sugar. Up till about

three years ago, when a refinery was started in Ireland, nearly all the

refined sugar consumed in that division of the kingdom was supplied from

Greenock; and it is a remarkable fact that even yet the steamers trading to

Dublin, Cork, Londonderry, and Belfast, draw the greater part of their

freight from sugar, from 250 to 600 tierces being carried by them weekly.

With reference to the early

days of sugar-refining in the east of Scotland we find the following in

Arnot's "History of Edinburgh:" —"There is hardly any branch of manufacture

which in speculation affords a more undoubted success to the manufacturer,

and more general benefit to the country, than the baking or refining of

sugars; and we will venture to say that it has been owing alone to the want

of capital and conduct in its managers that it has not hitherto been

attended with remarkable success. Were this manufacture properly conducted a

trade might be established between the West Indies and the east coast of

Scotland. Sugars might be afforded to the consumer at an easier rate, the

planter and manufacturer might carry on an advantageous species of traffic,

and a great sum of money might be saved to the country which is annually

remitted to London for baked sugars. There are four sugar-houses on the east

coast of Scotland—at Edinburgh, Leith, Dundee, and Aberdeen. These at

present are mostly supplied from Glasgow. Now, supposing every house to use

500 hogsheads annually, these, amounting to 2000 hogsheads, with the usual

proportions of rum, cotton, coffee, mahogany, &c., would make cargoes for

ten or twelve sail of good ships; and these might return with cargoes of

linen, negroes' clothing, and the various other articles for which there is

a demand in the West Indies. Leith is the most centrical port for carrying

on such trade. Vessels can be fitted out there easier than from the Clyde,

and greatly lower than from London. Thus a saving would be made on the

article of freight; other charges would be likewise more moderate than

either in the Clyde or at London; and the sugars, when landed, would be

worth from four to five per. cent. more to the sugar-houses than if landed

either at Greenock or London. This, added to the savings on freight and

charges, would amount to a valuable consideration to the West India planter,

and should, no doubt, encourage him to make consignments to the port of

Leith. A house for baking of sugars was set up in Edinburgh A.D. 1751, and

the manufacture is still carried on by the company who instituted it. That

of Leith was begun in the year 1757 by a company consisting mostly of

bankers in Edinburgh; but in five years their capital was totally lost. For

some time the sugar-house remained unoccupied, till some gentlemen from

England took a lease of the subject, and revived the manufacture; but as

these wanted capital altogether, and were consequently obliged to fall upon

ruinous schemes for supporting a fictitious credit, they were speedily

involved in destruction. To them succeeded the Messrs Parkers, who kept up

the manufacture above five years. The house was then purchased by a set of

merchants in Leith, who, as they began with a sufficient capital, as they

have employed in the work the best refiners of sugar that could be procured

in London, and who, as they pay due attention to the business, promise to

conduct it with every prospect of success."

The father of Mr Macfie, M.P.

for the Leith Burghs, was a sugar- refiner many years ago in Leith. His

establishment, which stood in Elbe Street, South Leith, was destroyed by

fire. An extensive sugar-refining business leas long carried on in North

Leith by Messrs Schultze, and afterwards by Messrs Ferguson; but the house

has been shut for eight or ten years. About four years ago a number of

merchants in Edinburgh and Leith formed themselves into a company, and built

a sugar-refinery in Breadalbane Street, Leith, where, under the designation

of the Bonnington Sugar-Refining Company, they carry on an extensive and

thriving business. Their refinery is the most recently erected in Scotland,

and embraces all the latest improvements in the processes and appliances of

the trade. The refinery was partly built in 1865, but owing to an accident

it was not in operation until the following year. It is a

substantial-looking brick structure, arranged in blocks to suit the

requirements of the various departments. The raw sugar is deposited on

arrival in a large detached building, where it lies under Customs' bond, and

whence it is withdrawn as required for the supply of the works. The great

casks in which the sugar is imported weigh when full more than a ton each,

but a powerful steam elevator makes light work of transferring them to the

upper floor of the refinery. To follow them thither the visitor must ascend

a narrow iron stair, which winds round the well in which the elevator works.

The steps are black and clammy with the saccharine matter which finds its

way most persistently to all parts of such establishments. Treacle seems to

ooze from the iron hand-rail and from the brick lining of the stair. case,

so that contact with either becomes most undesirable. Up and still up the

stair .winds, until from its summit a peep over the railing would make one

giddy. Stepping through an arched opening, fitted with iron doors, the upper

floor is reached. There lie the great casks in an atmosphere quite as hot as

that which surrounded them when they were filled in the Indies. Men are busy

forcing out the "heads" of the casks, and discharging the sugar upon the

floor, through grated slits in which it quickly disappears. There are

several recognised qualities of sugar, some being so light-coloured and

clean that it would seem almost superfluous to subject it to refining; while

in other cases the stuff has a dark and uninviting appearance, which would

ensure its safety were the casks left open in the play-ground of any school.

As the casks are emptied they are placed into a large iron tank, and

subjected to the action of steam, which detaches all the sugar and

thoroughly cleanses the casks. The refined sugars are sent out in the casks

in which the raw material arrives, and, while the sugar is being operated

upon in the refinery, the casks are taken to the cooperage, where they

receive any necessary repair.

In. order to ascertain what

has become of the sugar that has disappeared so mysteriously through the

hatchways, it is necessary to descend to the floor beneath. Here are two

large circular iron vessels, called "blow-up cisterns," into which the raw

sugar descends from the floor above. Hot water is let into the cistern, and

an agitator, worked by steam, is kept going until the soluble matter is

completely reduced. The liquid is then drawn off and filtered, in order that

all insoluble matter may be removed. The filters consist of bags of stout

twilled cotton, which are suspended in iron chambers on a lower floor. When

the filters are in action steam is admitted to the chambers, which

facilitates the process. From this ordeal the liquor comes forth clear and

sparkling, but displaying a reddish tinge, the removal of which is the next

care of the refiner, and causes him nearly as much trouble and expense as

all the other operations put together.

The syrup is deprived of its

colour by being passed through powdered charcoal. This operation is carried

on in the charcoal-house, which adjoins and is nearly equal in extent to the

main building. Animal charcoal, prepared by burning bones, is the substance

used, and several hundreds of tons are constantly in use. The filtering-

vessels are made of cast iron, and are cylindrical in form, each measuring

fifteen feet in depth by nine in diameter. Into each filter are run about

twenty tons of charcoal, in grain resembling coarse sand. Liquor from the

bag filters is then allowed to flow in until the vessels are filled, when a

tap in the bottom is opened, and the syrup runs off in a colourless stream.

The charcoal loses its power of decolouring after being in use for two days,

and then it has to be revivified. It is first washed by making hot water

flow through it, then withdrawn from the filter, and brought to a red heat

in peculiarly constructed kilns or furnaces. This treatment completely

restores its powers. From the charcoal-house the syrup is pumped into great

iron cisterns placed on one of the floors of the main building, and thence

it is withdrawn to supply the pans.

Prior to the year 1812 the

only mode practised for concentrating the syrup, or bringing it to the

crystallising point, was boiling it in open copper vessels. In the year

mentioned, Mr Howard patented his vacuum pan, one of the most important

inventions in connection with sugar-refining. A high temperature destroys

the crystallising property of sugar, and converts it into treacle; and when

the old method of concentration was in use, great loss occurred in

consequence of the large proportion of treacle which was inevitably

produced. Mr Howard, having become acquainted with the well- known. fact

that liquids boil in vacuum at a much lower temperature than when exposed to

the air, applied it to the concentration of sugar with the most complete

success, and his pans are now universally employed. By the exercise of

ordinary diligence the formation of treacle is almost entirely prevented,

and the sugar is brought to much higher condition at one operation than it

could formerly be by repeated refining. The Bonnington Company have two pans

of the largest size and most perfect construction. Each is capable of

boiling twelve tons of sugar at a time, and the cost of the pair was, we

believe, L.3000. The body of a pan consists of a spherical copper vessel

nine or ten feet in diameter. The bottom is double, leaving a space of an

inch or two for the admission of steam. Inside the pan is a large copper

pipe of a spiral form, through which a current of steam flows while the pan

is in action. From the top of the pan a pipe leads to a large cylindrical

vessel whither all the vapour given. off by the sugar is drawn by an air

pump and condensed by a jet of cold water. An immense quantity of water is

required to supply the condensers, and it is drawn from cisterns on the roof

of the building. As the supply is limited, the water, after performing its

duty in the condensers, is pumped back to the cistern, and the same process

is repeated. After the pan is charged with syrup the heat is gradually

raised by increasing the flow of steam through the bottom casing and worm.

The liquid boils at a temperature of 150°, and care must be taken not to let

the heat get beyond what is barely essential for ebullition. The

sugar-boiler must exercise constant vigilance, especially when the liquid

begins to thicken. The pan is fitted with instruments showing the

temperature and the degree of rarity of the air; and there is a peep-hole

through which the sugar inside the pan may be seen. As the boiling proceeds,

the attendant withdraws samples by means of a peculiarly constructed testrod,

which extracts some of the contents of the pan without letting in air. By

taking a drop of the syrup between his finger and thumb, and drawing it out

into a thin film, he is able to note the progress of crystallisation. When a

certain degree of consistency has been attained, the greater portion of the

contents of the pan is drawn off into open copper vessels called

"granulators," and fresh liquor is run into the pan.

Until a recent period, it was

customary to complete the process of crystallisation by filling the pulpy

stuff from the granulators into conical metallic moulds, which were set with

the apex down in an earthenware jar. An orifice in the point of the cone was

then opened, through which the uncrystallised syrup escaped. When the sugar

was drained sufficiently dry, all that remained to do was to put it into

casks and send it out. A much more expeditious mode of drying is now in

general use. A Belgian sugar- refiner conceived the idea of fastening a

number of the conical moulds on the rim of a large horizontal wheel, and

driving off the syrup by centrifugal force as the wheel was spun round at a

high rate of speed. An improvement in this method is the centrifugal

drying-machine, now extensively employed in manufactories of various kinds.

The machine consists of a circular vessel about four feet in diameter and

eighteen inches deep. The bottom is formed of iron, and the sides of fine

wire-gauze. Enclosing this vessel, at a distance of a few inches from the

gauze, is a strong casing of iron. The vessel is attached to a vertical axle

and gearing capable of causing it to spin round at the rate of a thousand

revolutions a minute. At the Bonnington Company's Refinery there are six

such machines on the floor beneath the pans and granulators. The semi-fluid

sugar is conveyed from the granulators to the centrifugal machines in a

waggon which runs on a railway placed at a convenient elevation. About a

hundredweight is put into each machine, and so speedily is the drying

accomplished, that three or four men are constantly employed in emptying the

machines in succession. Number one is dry by the time number six is filled,

and so the work goes on. The emptying is a speedy process—all that is

necessary being to stop the machine, open two valves in the bottom, and

shovel the sugar through them, when it falls into a truck placed to receive

it. The sugar does not have time to cool before these operations are

completed, and as it would not do to press the still warm sugar into casks,

it is raised to the cooling-floor, where it is spread out in a layer about a

foot in depth, and exposed to the free action of the air. When sufficiently

cooled it is packed, and either sent to market or stored. The syrup which is

driven off by the drying-machine is mixed with raw sugar in the "blow-up

cistern," and thus no particle of crystallisable matter is lost.

The establishment turns out

250 tons of refined sugar every week, in the production of which about 100

men are engaged. For driving the machinery six steam-engines of 80 horse

power in the aggregate are employed. Taking all the Scotch sugar-refineries

together, the number of workmen is over 2000, whose wages may be stated as

follows:—Boilers, L.200 to L.300 a-year; pan-men, 30s. to 40s. a-week;

filtermen, 17s.; warehousemen, 18s.; upstair's-men (general hands), 16s. to

17s.; charcoal kilnmen, 16s. to 18s. |