|

DISTILLING has been described

as "the art of evoking the fiery demon of drunkenness from his attempered

state in wine and beer." Though the Arabians from the remotest ages

extracted the aromatic essences of plants by distillation, no mention of the

production of an intoxicating spirit by the same mode occurs until the

eleventh century. It is first alluded to by an Arabian physician; but the

discovery is believed by some authors to have been made in one of the

northern countries of Europe. Another physician, who wrote in the thirteenth

century, refers explicitly to an intoxicating spirit obtained by the

distillation of wine, and he describes it as a recent discovery. So

delighted was the physician by the effect of the spirit, that he pronounced

it to be the panacea, or cure for all evils and disorders, ao long sought

after in vain. It need hardly be said that many persons still hold a similar

belief in the virtues of alcohol. Raymond Lully, the famous chemist of

Majorca, who was a disciple of the physician last referred to, claims for

alcohol an important mission. He describes "the admirable essence" to be "an

emanation of the divinity—an element newly revealed to man, but hid from

antiquity, because the human race were then too young to need this beverage,

destined to revive the energies of modern decrepitude." He further imagined

that the discovery of the aqua vile, as it was called, indicated the

approaching consummation of all things—the end of the world. The process of

distillation was thus described by Lully "Limpid and well-flavoured red or

white wine is to be digested during twenty days in a close vessel by the

heat of fermenting horse-dung, and to be then distilled in a sand-bath with

a very gentle fire. The true water of life will come over in precious drops,

which, being rectified by three or four successive distillations, will

afford--the wonderful quintessence of wine."

Great Scotch Whisky

(Documentary)

From its birthplace, the art

of producing ardent spirits by distillation slowly extended over Europe. No

reliable information exists as to the date of its introduction into Britain.

It is certain, however, that spirits were imported as early as 1430. The

French applied themselves to the distillation of brandy from wine, and were

so successful that their country came to be spoken of as the great

still-house of Europe, England being one of their best customers. Meanwhile,

the people of England had made some progress in agriculture; and grain

having in consequence become plentiful, they began to distil spirits from

it. The home-made article appeared to suit their palates better than the

French product; and the manufacture of it was gradually developed into an

extensive branch of industry, which was visited with legislative patronage

in the reign of Charles II., when a duty of twopence was imposed on every

gallon of spirits.

The people of Scotland were

not far behind their neighbours in turning attention to distilling. They

preferred spirits to the wines which they obtained from the Continent and to

the beer which they brewed at home. No record exists of the introduction or

progress of the trade prior to 1708, when 50,844 gallons of spirits were

produced. A duty had been levied on the article before that time, and acted

as a partial check on its production. Though the trade did not increase so

rapidly as it probably would have done if there had been no tax, yet the

progress made by distillers was astonishing. In 1756 they made 433,811

gallons of spirits; but an increase in the rate of duty in that year had the

effect of causing a considerable falling off in the quantity produced. About

the year 1776 a demand for Scotch spirits sprang up in England, and large

quantities were sent thither. An import duty of 2s. 6d. a gallon was charged

in England; and an extensive system of smuggling also sprang up. It is

stated that in 1787 upwards of 300,000 gallons crossed the Border without

the knowledge of the Excise. The mode of charging duty on the spirits made

by the distillers gave place, in 1786, to a license duty according to the

capacity of the stills. The distillers soon found that, by altering the form

of the stills, they could increase the rate of production immensely.

Government, becoming aware of the ingenious device of the Scotch distillers,

raised the amount of license step by step, until, before the end of last

century, it amounted to L.64, 16s. 4d. per gallon of still contents in the

Lowlands, and to L.3 per gallon in the Highlands. Passing over many changes

that have taken place in the interval, it may be sufficient to state here

that the license duty at present payable by distillers is L.10, 10s., with

10s. of spirit-duty for every gallon of whisky sent out for home

consumption.

Eighty or ninety years ago

the illicit manufacture of whisky was common throughout the Highlands. At

first the "sma' stills" were set to work to produce a supply of whisky for

the use of the owners and their friends; but as the restrictions on licensed

distillers were increased, the proprietors of the unlicensed stills were

encouraged to extend their operations, and to enter into competition with

the legal manufacturers. Then began that system of smuggling which made a

certain class of Highlanders so notorious, and gave so much trouble to the

Excise department. The wild glens of the north afforded secure retreats for

the working of the stills; and many ingenious modes of conveying the produce

to market were devised. The tendency was to demoralise the smugglers, and

cast them back towards barbarism. They became reckless and daring to an

extraordinary degree, and the stories of smuggling adventures record the

performance of acts which, had they been rendered in a legitimate service,

would have conferred undying honour on the actors. A man who could "jink the

gauger" was a hero in the little circle in which he moved, and the people of

the rural districts generally hailed with delight the performance of any

deed which set the Excise laws at defiance. Even persons in authority winked

at the breach of those laws. The great strongholds of the smugglers in the

north were Glenlivet, Strathden, and the Glen of New Mill. The proprietor of

the only distillery now in Glenlivet recollects seeing 200 illicit stills at

work in Glenlivet alone. Owing to the quality of the water and other causes,

the whisky made in the Glen became famous—indeed, smuggled whisky generally

was preferred by consumers, on account of its mildness and fine flavour. The

solitary distillery in. the Glen has an interesting history, and the spirits

made at it retain the old renown. Mr George Smith, the proprietor of the

distillery, was the pioneer of licensed distilling in the Highlands, and he

recently supplied to a correspondent of the "London Scotsman" the following

account of the origin of his establishment, which is worth reproducing:-

"About this time (1820), the

Government, giving its mind to internal reforms, began to awaken to the fact

that it might be possible to realise a considerable revenue from the whisky

duty north of the Grampians. No doubt they were helped to this conviction by

the grumbling of the south country distillers, whose profits were destroyed

by the quantity of kegs which used to come streaming down-the mountain

passes. But through long impunity the Highlands had become demoralised, and

the authorities thought it would be safer to use policy than force. The

question was frequently debated in both Houses of Parliament, and strong

representations made to the north country proprietors to use their influence

in the cause of law and order. Pressure of this sort was brought to bear

very strongly upon Alexander, Duke of Gordon, who at length was stirred up

to make a reply. The Highlanders, he said, were born distillers; whisky was

their beverage from time immemorial, and they would have it, and would sell

it too, when tempted by so largo a duty; but, said Duke Alexander, if the

Legislature would pass an Act, affording an opening for the manufacture of

whisky as good as the smuggled product, at a reasonable duty easily payable,

he and his brother proprietors of the Highlands would use their best

endeavours to put down smuggling and to encourage legal distillation. As the

outcome of this pledge, a bill was passed in 1823, to include Scotland,

sanctioning legal distillation at a duty of 2s. 3d. per wine gallon proof

spirit, with L.10 license for any seized still above forty gallons; none

under that seize being allowed.

"This would seem a heavy blow

to smuggling; and for a year or two before the farce of an attempt had been

made to inflict a L.20 penalty where any quantity of smuggled whisky was

found manufactured or in process of manufacture. But there were no means of

enforcing such a penalty, for the smugglers laughed at attempts of seizure;

and when the new Act was heard of, both in Glenlivet and in the Highlands of

Aberdeenshire, they ridiculed the idea that any one would be found daring

enough to commence legal distillation in their midst. The proprietors were

very anxious to fulfil their pledges to Government, and did everything they

could to encourage the commencement of legal distillation; but the desperate

character of the smugglers and the violence of their threats deterred any

one for some time. At length, in 1824, I, George Smith, who was then a

powerful robust young fellow, and not given to be easily 'fleggit,'

determined to chance it. I was already a tenant of the Duke, and received

every encouragement in my undertaking from his Grace himself, and his

factor, Mr Skinner. The lookout was an ugly one, though. I was warned before

I began by my civil neighbours that they meant to burn the new distillery to

the ground, and me in the heart of it. The laird of Aberlour presented me

with a pair of hair-trigger pistols, worth ten guineas, and they were never

out of my belt for years. I got together two or three stout fellows for

servants, armed them with pistols, and let it be known everywhere that I

would fight for my place till the last shot. I had a pretty good character

as a man of my word, and through watching, by turns, every night for years,

we contrived to save the distillery from the fate so freely predicted for

it. But I often, both at kirk and market, had rough times of it among the

glen people; and if it had not been for the laird of Aberlour's pistols, I

don't think I should have been telling you this story now. In 1825 and '26

three more small legal distilleries were commenced in the Glen; but the

smugglers succeeded very soon in frightening away their occupants, none of

whom ventured to bang on a single year in the face of the threats uttered so

freely against them. Threats were not the only weapons used. In 1825 a

distillery which had just been started at the head of Aberdeenshire, near

the Banks o' Dee, was burned to the ground with all its out-buildings and

appliances, and the distiller had a very narrow escape from being roasted in

his own kiln. The country was in a desperately lawless state at this time.

The riding officers of the revenue were the mere sport of the smugglers, and

nothing was more common than for them to be shown a still at work, and then

coolly defied to make a seizure."

A rare trip into Whisky

heaven

When distillers Laphroaig launched their first ever live online whisky

tasting, an army of malt fans from around the world made it the largest

interactive event of its kind.

From New Zealand to Sweden, New York to Sydney, thousands of you watched the

live WebTV show in London and mailed in hundreds of questions to the eminent

panel of distillers, connoisseurs and writers.

Now you have the chance to join in an even bigger event live from the

Laphroaig distillery on the Scottish island of Islay. The distillery sits on

the South coast of the island with views of both Scotland and Ireland and

the show will be broadcast from inside the distillerys original bonded

warehouse number one normally only accessible to distillery staff and

customs officers.

So if you love whisky but are keen to know more about those wonderful single

malts and how they are blended to taste so good we have a treat for you this

evening. Master blender Robert Hicks and Distillery Manager John Campbell

will host an exclusive tasting session, which includes four Laphroaig malts,

the highlight being a new Quarter Cask triple wood, drawn and tasted live

from a sherry cask.

They will be joined by writer Martine Nouet, Keeper of the Quaich, and if

you want to know what that means you will need to join the live show to find

out.

Our guests will take you through all the finer points of getting the best

out of a single malt whisky, from the colour, weight and nose to the all

important taste and finish. How much water, if any, should you add to your

glass? What do the aromas tell you about the whisky? Which flavours and

textures should you be expecting as the whisky hits your palate?

Robert Hicks, Laphroaigs Master Blender, John Campbell, Distillery Manager,

and whisky writer Martine Nouet join us live online on Wednesday 18th June

at 8pm for a live whisky tasting.

Though smuggling was most

extensively carried on in the Highland regions, the trade was not limited to

them, and unlicensed stills have been discovered in situations which might

be considered beyond the breath of suspicion. In Arnot's "History of

Edinburgh," it is stated that, while in 1777 there were only 8 licensed

stills in Edinburgh, the unlicensed numbered 400. In July 1815, a "private"

distillery of considerable extent, which had been in operation for eighteen

months, was discovered under an arch of the South Bridge in Edinburgh. The

bridge consists of a large number of arches, only one of which is open, the

others being blocked up by the houses which line the bridge on both sides.

It was in one of the arches adjoining the open one that the distillery had

been set up. All the arrangements for conducting the business without the

knowledge of the Excise officers were of the most complete kind. The only

entrance to the place was by a doorway situated behind the grate of a

bedroom in a house on one of the lower flats adjoining the bridge. Between

this doorway and the distillery communication was established by means of a

ladder and trap-door. A supply of water was obtained from a branch attached

to one of the mains of the Water Company which passed overhead, and the

smoke and waste were got rid of by making an opening in the chimney of one

of the adjoining houses, and establishing a communication with the

soil-pipes. The spirits were sent out in a tin case capable of con-taming

two or three gallons. The case was placed in a bag, and taken to the

customers by a woman in the service. When the place was entered by the

officers of the law, a large quantity of material and all the appliances

employed in the manufacture of whisky were found. A number of years ago a

secret distillery was discovered in the cellars under the Free Tron Church,

in the High Street of Edinburgh; and soon afterwards, an extensive concern

of the same kind was revealed at Marionville, between Edinburgh and

Portobello. More recently, a still was seized at work almost within a

stone-throw of the Excise office in Aberdeen, and subsequently there was a

"seizure" in a close in the centre of Leith. Not long since, a still was

discovered in England beneath the pulpit of a church; and only the other day

a thriving business in Nottingham was interrupted in consequence of the

absence of the all-important license.

In the year 1799 there were

87 licensed distillers in Scotland, who paid duty on spirits retained for

home consumption to the amount of L.1,620,388. That was the first year of

the change in the mode of levying duty. Previously so much was paid

according to the capacity of the still, but now a. 4s. 101d. duty was laid

on every gallon of spirits made for home consumption. The change was not

approved of by the distillers, about a third of whom gave up business in the

following year, and the duty decreased to L.775,750. The lowering of the

duty to 3s. 10d. in 1802 revived the trade, and the returns for 1803 showed

88 distillers paying L.2,022,409. In 1804 progress was checked by another

advance in the duty, and the number of distillers dwindled down until, in

1813, there were only 24. The duty reached 9s. 4zd. a-gallon in 1815, but

the produce was considerably under a million pounds. It is probable,

however, that the quantity of whisky actually made in the country was

greater than at any previous time, the high duty tending, as already stated,

to foster illicit distillation and smuggling. The lowering of the duty to

2s. 4d. in 1823 had the effect of giving an impetus to the trade. The number

of licensed distillers greatly increased, and the revenue rose steadily.

There were 243 distillers in 1833, who paid duty to the amount of

L.5,988,556, the rate then being 3s. 4d. a-gallon.

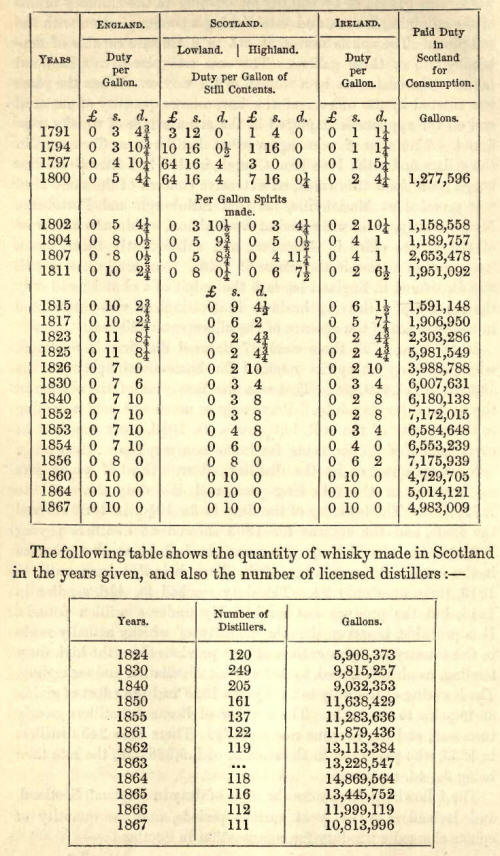

The following table shows the

rates of duty in England, Scotland. and Ireland respectively at various

periods, and the quantity of spirits charged with duty for consumption in

Scotland :-

The two most extensive

distilleries in Scotland are the Port-Dundas Distillery in Glasgow, which

belongs to Messrs M. M'Farlane and Co., and the Caledonian Distillery, in

Edinburgh, owned by Messrs Menzies, Bernard, & Co. The latter has been

chosen to illustrate the processes of distillation. The establishment covers

five acres of ground at the west end of the city, in a situation most

convenient for carrying on a large trade. It is one of the most recently

erected distilleries in the country, having been built in 1855; and every

part of it has been constructed according to the latest improvements in the

trade. All the principal buildings are five storeys in height, and are so

arranged that the labour of carrying the materials through the various

stages of manufacture is reduced to the smallest amount. A branch line from

the Caledonian and another from the North British Railway converge in the

centre of the works, and afford ready and convenient accommodation for

bringing in the raw materials and sending out the products. The extent of

this traffic may be judged from the facts that 2000 qrs. of grain and 200

tons of coal are used every week, while the quantity of spirits sent out in

the same time is 40,000 gallons, the duty on which is L.20,000, or at the

rate of L.1,040,000 a-year. The machinery is propelled by five steam-engines

of from 5 to 150 horse power, for the service of which, and supplying the

steam used in distilling, there are nine large steam-boilers.

The Caledonian is one of the

eight distilleries in Scotland which produce "grain whisky," the others

making malt whisky only. The kinds of grain used are maize, rye, buckwheat,

oats, and barley. The latter is converted into malt, which is used in

certain proportions with the other grains in a raw state. Most of the grain

is imported into Granton, whence it is brought, by rail, in special trucks

to the distillery. The trucks hold fifty quarters each, and when they arrive

they are taken one after the other to a part of the line adjoining the

stores and malting premises. Beneath the spot to which they are brought is a

pit, forming the terminus of an Archimedean screw and tunnel. The opening of

a valve in the bottom of the truck allows the grain to run into the pit,

from which the screw draws it along to a hopper inside the building. From

the hopper it is carried by belt and bucket apparatus to the store on the

upper floor, where other sets of screws carry it along and deposit it in an

even layer on the floor—so that no manual labour is required in this part of

the work. The contents of two trucks, or 100 quarters, are thus disposed of

in an hour. The stores have accommodation for 10,000 quarters. As most of

the grain used has to be dried as well as the malt, the kilns are very

extensive, and are capable of drying about 400 quarters a-day. One of the

kilns is heated by the waste steam from one of the engines, and the others

are fired with coke. The malt-barns are capable of producing about 600

quarters a-week. From the kilns the malt and grain are transferred to the

mill, where the former is bruised between rollers, and the latter ground

into meal by means of common mill-stones.

The next process is the

mashing, which works a wonderful change on the constituents of the grain,

converting a large proportion of them into starch-sugar, which is the prime

source of alcohol. In the mashing department are four wort and water tanks,

capable of containing 30,000 gallons each, and five mash-tons of from 10,000

to 30,000 gallons. Water, at a temperature of about 160°, is run into the

tons, and then the "grist" is added, the compound being mixed thoroughly by

a set of revolving rakes. Many nice points have to be considered in this as

in the other processes of spirit manufacture. The proportion of different

kinds of grain used in the mash determines the temperature to which the

water should be raised, and also the duration of the process. Malt is more

easily mashed than a mixture with raw grain; but the latter produces a

greater proportion of spirit. The saccharine matter extracted in mashing is

held in solution by the water, and so drawn off. When the mashing is

completed, the liquid is run into large tons called "underbacks," leaving

the spent grains, or drafl', in the mash-ton. At this stage the liquid is

known as "wort." The wort contains the elements of alcohol; but another

process—that of fermentation—is necessary for the entire conversion. Before

being subjected to fermentation, the wort must, as speedily as possible, be

cooled to a certain point. For this purpose it is pumped from the underbacks

to a large cistern at the top of the building, from which it flows into

refrigerators. Cooling used to be effected by running the liquid into

shallow iron troughs, and causing currents of cold air to sweep over it. In

order to cool the produce at this great establishment, several acres of such

coolers would have been required ; but the invention of the refrigerator has

made it possible to do all the cooling in very little space, and in much

less time than by the old method. The refrigerator consists of a range of

tall copper cylinders, inside of which a number of tubes are so arranged

that while the wort flows through them, a current of cold water passes over

the outside, so that, as the liquid traverses the cylinders it is cooled to

the requisite degree. From the refrigerator the wort passes to the

fermentingroom—a great apartment occupied by twelve tuns of 50,000 gallons

each. Distillers have to work under regulations designed for the convenience

of the Excise department, and certain things have to be done on certain

days. Thus the distilling process is carried on during Monday and Tuesday,

while the mashing and brewing occupy the remainder of the week. The

distillers consider this compulsory idleness of their fermenting plant while

the distilling is in progress to be a great hardship, and a movement has

been made on several occasions to obtain power to carry on the manufacture

of beer as well as of whisky, but the privilege has hitherto been refused.

When the tuns are filled with wort, yeast is added, and the process of

fermentation goes on, under survey of Excise officers, of whom no fewer than

eleven are stationed on the Caledonian Distillery. By fermentation and the

decomposition of the sugar alcohol is developed in the wort. When the

fermentation is completed, the liquid, which then receives the name of

"wash," is measured, and its strength ascertained by the Excise officers.

All that now remains to be

done is to extract the alcohol from the wash. This is done by distillation.

The stills first used were exceedingly simple in their form and mode of

action, but were suitable only for dealing with small quantities of liquor.

The common still was brought to the highest degree of perfection in Scotland

during the time that the method of charging duty according to the capacity

of the stills prevailed. Charging in that way led the distillers to devise

stills which would produce a greater quantity of spirit in a given time than

those of the old form were equal to. They made their stills broad and

shallow, so that a larger surface was exposed to the fire. But an entire

change in the form of the apparatus was subsequently effected. In 1832 Mr

Æneas Coffey, Inspector-General of Excise in Ireland, patented a still

which, as finally improved, is the best apparatus in use for the production

on a large scale of a rectified spirit of high strength, with the greatest

economy of time and fuel. In most of the extensive distilleries Coffey's

still is employed. The Caledonian Distillery contains the largest still in

Scotland. Before describing its mode of action, it may be well to state

generally the scientific principle involved in the process of distillation.

Alcohol is more volatile than water. Pure alcohol boils at 173°, water at

212°, while mixtures of the two liquids boil at an intermediate temperature.

Therefore, when the wash is raised to the boiling point of alcohol, the

latter is converted into vapour, and passes off into a condenser. Some water

and a portion of fusel oil are carried along with the alcoholic vapour in

distillation after the old method, and have to be separated by the "low

wines," as the produce of the first operation is called, being passed

through the still again and again until the desired degree of purity is

attained. With Coffey's apparatus the distillation is completed at one

operation. The cold wash flows in at one part of the still, and at another a

strong sparkling spirit gushes forth at the rate of 1000 gallons an hour.

Coffey's still consists of two columns—one called the analyzer and the other

the rectifier—each forty feet in height; and the wash, in passing through

them, loses its alcohol by evaporation, which is due to the action of steam

on a system of copper pipes and perforated trays. The apparatus is so

constructed that it is impossible for spirit of less than a certain degree

of strength and purity to pass out of it. The product of this still is a

"neutral spirit," which, being deprived of all essential oils, is, when

matured by age, considered by some consumers the most wholesome. A great

quantity of it is sent to London, where it is converted into brandy and gin

by the addition of flavouring ingredients. In the still-room is a large

rectifier, by means of which some of the spirit from Coffey's still is

brought to a higher degree of purity.

In order to meet a growing

demand for the variety of whisky known as "Irish," the proprietors of the

Caledonian distillery, about two years ago, fitted up two large stills of

the old pattern, with which they manufacture whisky similar to that made in

Dublin. In connection with this branch of the business, stores capable of

accommodating about 5000 puncheons have recently been constructed, in which

the various kinds of whisky are allowed to lie for some time before being

sent out.

In proportion to the amount

of money turned over, fewer work-people are engaged in distilling and

brewing than perhaps in any other branch of manufacture, as is proved by the

fact that in this great establishment only 150 men are employed. The plant

and stock, however, represent immense capital.

See also

Highland

Park - An Introduction to Highland Park and its history |