|

THE art of preparing

beverages from fermented grain is of great antiquity. It was, according to

Herodotus, practised by the Egyptians; Pliny the elder states that it was

known to the western nations; and Tacitus mentions that a fermented liquor

extracted from grain was the common beverage of the ancient Germans. One of

the pleasures promised to Scandinavian heroes was that in their Valhalla, or

Palace of the Gods, they should drink ale out of carved horns. A favourite

beverage of the Anglo-Saxons in the fifth century was a kind of ale made

from grain; and among the civic officers of the time were "ale-conners,"

whose business it was to taste the liquor offered for sale, and fix its

price. In. the parish of Minnigaff, Kirkcudbrightshire, are remains of some

kilns which tradition alleges to have been constructed by the Picts for the

purpose of brewing ale from heather. The earliest mention of "ale-houses" in

England occurs in 1014, and about that period the price of ale was fixed by

law.

In Scotland the "broustaris,"

or brewers, were taken cognisance of in the Leges Burgorum, a code of burgh

laws sanctioned by the Legislature in the twelfth century. Under those laws

a licence-duty at the rate of 4d. a-year was imposed on all persons engaged

in brewing. Another clause, entitled "Of the manner of ale brewing be assise,"

is as follows:—"What woman that wil brew ale to sell sall brew al the yhere

thruch eftir the custume of the toune. And gif scho dois nocht scho sall be

suspendyt of hir office be the space of a yhere and a day. And scho sall mak

gud ale approbabill as the ty e askis. And gif scho makis ivil ale and dois

agane the custume of the tonne and be convykkyt of it, scho sall gif til hir

mercyment viii. s., or than thole the lauch of the toune—that is to say, be

put on the kukstule, and the ale sall be geyflin to the pure folk the twa

part, and the thryd part send to the brethyr of the hospitale. And rycht sic

dome sal be done of maid as of ale. And ilk browstare sal put hit alewande

ututh hir house at hir wyndow or abune hir dur that it may be seabill

communly til al men, the whilk gif scho dois nocht scho sal pay for hir

defalt iiij d." This shows that the brewing business was originally in the

hands of women, and there is evidence that it continued to be so for many

years subsequent to the passing of the laws referred to.

In the fourteenth century a

list was drawn up of matters to be inquired into by the Chamberlain of each

burgh in his term of office. The following "items" will show that brewers

were to be particularly looked after:—"Also, gif the Baffles have executed

judgment upon baksters, browster men and women, after they be amerced. Also,

gif browster-wives sel aill be quart and be just measures. Also, gif

browster-wives brewe and selle aill conform to the price set upon it by the

taisters. And gif they selle before the aill has been prised by the taisters.

Also, gif browster-wives sell their aill by potsful, and not by sealed

measure. Also, how many of the browster-wives were amerced in the year.

Also, gif any man keip hand mylnes, other than are burges, and brewes and

maks malt, composition not made, and wha manteins them."

In the year 1124 the price of

a Scotch gallon of ale was equal to 6d. of modern money. In 1562 the price

of a pint of ale is stated in the Council Register to have been 9d. The

records of the Scotch Privy Council show that, in 1666, the price of ale was

fixed as follows, in sterling money:—"When rough here is 10s. per boll,

Linlithgow measure, then ale shall be sold, per Scotch pint, at ld.; with

the addition of one-sixth of a penny as excise in country parishes, and

one-sixth more in the city of Edinburgh. When bare is at 13s. 4d., the pint

of ale shall be 1d.; when at 16s. 8d., the pint of ale shall be 2d." Ale was

in those days an article of consumption in every household and at every

meal. The upper classes drank wine, which they obtained at the following

rates:—Bordeaux wine, if imported by the east sea, 3s. 11d. per Scotch pint

(equal to about 11 imperial quarts); ditto, by the west sea, 2s. 6d.

Rochelle wine, if imported by the east sea, 2s. 6d.; ditto, by the west sea,

Is. 101d. An Englishman who visited Edinburgh in 1598 wrote:—"The Scots

drink pure wines, not with sugar as the English; yet at feasts they put

comfits in. the wine, after the French manner, but they had not our

vintners' fraud to mix their wines. I did never see nor hear that they have

any public inns with signs hanging out; but the better sort of citizens brew

ale, their usual drink (which will distemper a stranger's body)." The usual

allowance of ale at table was a chopin (equal to about an imperial quart) to

each person.

For many years the

inhabitants of the City Parish of Edinburgh paid a tax of 2d. on every

Scotch pint of ale they consumed, and that was continued after the

imposition of a tax by Government. In the year 1690 this local tax produced

L.4000. In 1723 the tax was extended to the parishes of St Cuthbert's,

Canongate, and South and North Leith, and with the money which it was

expected would flow into the municipal treasury from this source many good

things were to be done. The stipends of the city ministers and the salaries

of professors were to be augmented, an increased supply of water was to be

brought in, and public buildings were to be erected. The imposition. was

ill-timed, for the people were beginning to cultivate a taste for a more

potent preparation from malt, and to find out the virtues of tea. The tax

produced L.7939 in the first year of its operation over the extended area;

but never again did it reach that figure. In 1776 it had dwindled down to

L.2197; and moralists were loud in their wails over the fact that "the use

of that destructive spirit (whisky) was increasing among the common people

of all ages and sexes with a rapidity which threatened the most important

effects upon society." After a time the tax was abolished, but the domestic

use of ale has never again been so common as it was a hundred and fifty

years ago.

In 1643 a duty was imposed on

the ale produced at public breweries in England. This tax was subsequently

levied in Scot-land, and continued till 1830, when it was repealed. In

England malt was subjected to a tax of 6d. a bushel in 1695, and the tax was

extended to Scotland in 1725. The Scotch people submitted very unwillingly

to the imposition, and strong manifestations were made against it in both

Edinburgh and Glasgow. In the latter city riots occurred which resulted in

the death of nine and the wounding of seventeen persons. Mr Campbell of

Shawfield, the member for the Glasgow district of burghs, had rendered

himself obnoxious to a large body of the citizens, by voting in Parliament

for the extension of the tax to Scotland, and on the 23d June 1725, the day

on which the tax came into operation, a mob assembled, obstructed the

excisemen, and assumed such a threatening attitude, that on the evening of

the next day, two companies of soldiers, under the command of Captain

Bushel, entered the city. The appearance of the military did not overawe the

mob, nor deter them from making an attack on Mr Campbell's house, then one

of the finest in Glasgow. While the magistrates were spending the evening in

a tavern, and the soldiers were at their barracks, a mob marched to

Shawfield House, the furniture and fittings of which they completely

demolished. Mr Campbell and his family had removed to their country

residence a few days previously. The captain of the soldiers having learned

what had been done, sent to the Provost to ask for instructions; but the

proffered services of the military were declined Emboldened by the success

they had achieved so far in carrying out their designs, the mob next day set

themselves to molest the soldiers. After his men had withstood several

volleys of stones, Captain Bushel gave the order to fire on the mob, and two

persons were killed and several wounded. Finding themselves at a

disadvantage against the muskets of the soldiers, the mob broke into the

town-house magazine, and carried off the arms. At the request of the

Provost, Captain Bushel removed his men towards Dumbarton, but they were

overtaken on the way, and a sharp encounter took place. The military fired

on the people, and several were killed and wounded. On information of the

riots reaching headquarters, General Wade, with a large body of troops, took

possession of the city. The Lord Advocate accompanied the General, and made

an investigation into the circumstances of the disturbances, the result of

which was that nineteen persons were apprehended, bound with ropes, and

delivered over to Captain Bushel, who conveyed them to Edinburgh, and lodged

them in the Castle. At the same time the whole of the magistrates were

apprehended, and taken to Edinburgh. The charge against them was that they

had favoured the rioters, and winked at the destruction of Shawfield House;

but that charge was not substantiated; and after being a day in custody they

were released on bail, and subsequently absolved. The nineteen inferior

persons were punished in various ways—two were banished for life, some were

sentenced to long terms of imprisonment, and others were whipped through the

streets of Glasgow. By order of Parliament the citizens had to pay L.9000 to

Mr Campbell as indemnity for his loss.

The riots left many bitter

recollections in Glasgow, and did not tend to allay the popular feeling

against the malt-tax. In the following year the duty was reduced to 3d. a

bushel. Subsequently the rate underwent many fluctuations. In England, in

1760, it was raised to 9d. a bushel; in 1780 it was raised to ls. 4d. a

bushel, and to 8d. a bushel in Scotland. In 1785 the duty was imposed in

Ireland at 7d. a bushel; and raised in 1795 to is. 3d. In 1802 it was

respectively 2s. 5d. in England, ls. 8d. in Scotland, and ls. 9p. in

Ireland. In. 1804, which was a year of war tax, it was raised to 4s. 5P. in

England, to 3s. 9P. in Scotland, and to 2s. 3A d. in Ireland. In 1813 it was

raised to 3s. 3d. in Ireland; and in. 1815 it was further raised to 4s. 5d.

In 1816 the duty was reduced to what it had been prior to 1804, namely, 2s.

5d. in England, and ls. 8p. in Scotland, but it was reduced to 1s. 4d. in

Ireland. In 1819 it was raised to 3s. 7d. in England and Scotland, and 3s.

6d. in Ireland. In 1822 the duty was fixed at 2s. 7d. uniformly, at which

rate it stands at the present time, with the exception of 5 per cent., which

was added in 1840 to the Excise duties generally, making the actual impost

2s. 8d. During the Crimean war the duty was raised to 4s., and after the war

it reverted to 2s. 8d.

Like other branches of trade

which had long been conducted on a small scale in the ordinary dwellings of

the people, brewing was about two centuries ago developed into a wholesale

manufacture, and carried on in buildings specially fitted up. There are no

statistics to show what the extent of the trade was in those early days; but

for many years the production was limited to home requirements. In the

beginning of last century ale and beer were exported from Leith to several

continental countries. Since that time the export trade has gone on

extending, and a marked increase has taken place within the past eight or

ten years. The brewing trade is becoming concentrated into fewer hands, and

operations are in some cases conducted on a gigantic scale. In the year 1835

there were 640 persons licensed to brew beer in Scotland. By 1863 these were

reduced to 225, and in 1866 the number was 217, of whom 98 were brewers, and

119 victuallers who brewed their own beer. In 1836 the Scotch brewers

consumed 1,137,176 bushels of malt; in 1863, 1,780,919 bushels; and in 1866,

2,499,019 bushels. The exports of ale and beer in 1863 amounted to 47,415

barrels of 36 gallons each, the declared value of which was L.172,140; in

1866 the quantity sent out was 61,723 barrels, valued at L.230,109. In order

to show the wide connection which the brewers have established, the places

to which the last mentioned quantity of beer was sent may be stated:- 1370

barrels went to Hamburg, 1250 to Mauritius, 13,975 to the continental

territories of British India, 1564 to Singapore, 4337 to Victoria, 455 to

New South Wales, 557 to Queensland, 1420 to New Zealand, 1904 to British

North America, 8797 to the British West Indies, 5161 to Foreign West Indies,

3346 to the United States, 956 to Chili, 2715 to Brazil, 3636 to Uraguay,

and 5965 to the Argentine Republic. In 1867 there were 66,909 barrels

exported.

The Edinburgh brewers have

long been famous for the superior quality of their ales and beers, and their

trade forms one of the most important branches of manufacturing industry in

the city. The names of Younger, Jeffrey, Drybrough, Campbell, Usher, and

others, are familiar wherever Scotch ale is consumed, and that signifies, as

shown above, that they are known in every quarter of the world. A

description of the malting and brewing establishments of Messrs J. Jeffrey &

Co., of the Heriot Brewery, will convey some idea of the mode in which an

extensive business of this kind is carried on. The malting premises,

bottling-house, and ale stores of this firm are at Roseburn, at the extreme

west end of the city, while their brewery is in the Grassmarket. This

separation is a considerable inconvenience; but as the brewery, by repeated

extensions, occupied every inch of available ground, it became imperative,

when further extension was required, to sever the connection between the

malting and brewing departments. Accordingly, a year or two ago, the firm

acquired a site at Roseburn, adjoining the Caledonian Railway, and erected

thereon malting premises and stores of great extent, and fitted up in the

most complete manner. The malt-barn is a substantially constructed building

of five floors, and measures 320 feet in length by 90 feet in breadth. On

the upper floor the barley is stored in bulk, being raised to that part of

the building by means of belt-and-bucket gearing, communicating with

horizontal tubes fixed overhead, through which Archimedean screws draw the

grain along to any point desired. From the store the grain is transferred,

as required, to the floors beneath, by means of tubes or shoots.

The process of malting

embraces four operations—namely, steeping, couching, flooring, and

kiln-drying—the object of all being to force the barley to germinate, and

then to check the germination at g certain point. Across the end of each of

the malting floors is a steep capable of containing 84 quarters of barley.

The grain is run into the steep from the store-loft, and when the steep is

partly filled, water is allowed to flow in. After the grain has been steeped

for about sixty hours, the superfluous water is run off, and the barley is

thrown out of the steep. At this stage it is measured by the Excise

officers, and charged with malt duty. It is then "couched," that is, allowed

to lie in a heap on the floor for twenty-six hours or so, during which time

its temperature rises about ten degrees, and it gives off some of the

superfluous water. This "sweating," as it is termed, is the result of the

partial germination of the barley. On examining the grain at this stage, it

is seen that rootlets have begun to appear, and traces of a stem may be

detected beneath the husk. Now is the time for "flooring." The barley is

spread in an even layer on the floor, to a depth of six or eight inches, and

as it dries it is frequently turned. This operation extends over several

days, at the end of which the barley is placed in a kiln and dried

thoroughly. The action of the kiln in drying is not confined to expelling

the moisture from the germinated grain, but serves to convert into sugar a

portion of the starch which remained unchanged. Malt is generally

distinguished by its colour—as pale, amber, brown, or black malt—arising

from the different degrees of heat and the management in drying. The pale

and amber coloured varieties are used for brewing the lighter kinds of beer;

a darker variety is used for sweet ale; and the darkest for porter.

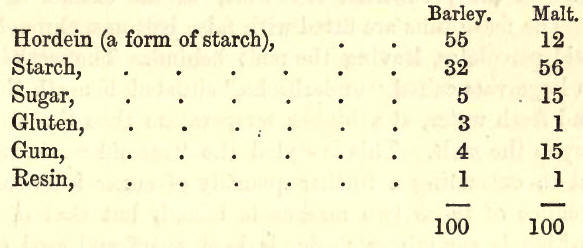

A remarkable change takes

place in the grain during its conversion into malt, as will appear from the

following analysis:—

These figures show that the

amount of the convertible starch and sugar has been nearly doubled at the

expense of the hordein, a portion of which has also passed into the

condition of mucilage, or a soluble gum, while the gluten is reduced to

one-third of its original quantity. In converting barley into malt a loss of

material occurs. Thus, 100 lb. of barley yield only 80 Th. of malt; but, on

the other hand, there is an increase in bulk, 100 measures of barley

yielding 101 to 109 measures of malt. This change in weight and bulk may be

tested by casting some grains of barley and malt into water, when it will be

seen that, while the barley sinks at once, the malt keeps afloat.

In order to see how beer is

made, the malt must be followed to the brewery. The Heriot Brewery has been

in operation for a century, and for upwards of thirty years it has been in

the possession of Messrs Jeffrey. Like most works which have been gradually

extended from small beginnings on limited sites, the brewery is not arranged

according to modern ideas of such establishments; but that drawback apart,

the place is complete in all its appointments, and the more recent additions

have been made according to the most advanced views of the business. The

malt is raised to a large store-room on an upper floor, and thence it is

withdrawn to supply the mill The latter consists of a pair of steel

cylinders which bruise the malt—bruising being preferred to grinding, which

would make the malt become pasty when mixed with water. From the mill the

malt descends to the mashing-room. A new mode of mashing recently introduced

is here at work. Formerly the bruised malt was placed in the mashtun with a

certain quantity of hot water, and there stirred about by revolving rakes

till all the saccharine matter was dissolved. By the new method the malt

escapes from a hopper into a horizontal cylinder having a series of

revolving arms inside. At the same time the proper supply of water is

allowed to flow in, and, as the malt and water pass through the cylinder,

they are so completely mixed that they require no further mechanical

treatment for the production of "wort," as the extract of malt is called.

The mash-tuns are fitted with false bottoms, through which the liquid

percolates, leaving the malt behind. The wort is drawn off into large vats

called "underbacks," situated beneath the mash-tuns, and fresh water, at a

higher temperature than that first used, is run upon the malt. This is

styled the "second mash," and it is effectual in extracting a further

quantity of sugar from the grain. The produce of those two mashes is mixed,

but that of a third mash, which is sometimes made, is kept apart and used

either in brewing small beer or in treating the malt in a first mash. The

residue of the malt, under the name of "draff," is used as food for cattle.

The wort having been reduced

to the proper strength, is pumped from the "underbacks" to the

boiling-house, which is occupied by two copper boilers, each capable of

containing 5500 gallons. At this stage the hops are added according to the

kind of beer that is being made. The proportion of hops varies from 4 to 14

lb. to the quarter of malt. The boiling is continued until the aromatic and

bitter principles of the hops have been extracted, and the liquid has been

concentrated to the required degree. A tap in the bottom of the boiler is

then opened, and the liquid is run off into the "hop-back," a large iron

cistern with a perforated bottom. As the wort percolates through the bottom

of the cistern it runs into the "coolers," shallow troughs of iron covered

with a roof but open at the sides. There the liquid cools rapidly, but not

so rapidly as desired sometimes, and means are taken by fans and other

contrivances to send currents of air over the surface. Systems of tubes

called "refrigerators" are also used. The tubes are arranged in the form of

a -vertical screen, and as a current of cold water flows through them, the

wort is poured over them from above, and allowed to trickle from one to the

other. If the cooling be not effected rapidly, the sugar in the wort becomes

partially converted into acetic acid, and the quality of the beer is thereby

deteriorated. When the liquid has been cooled down to about 60° it is ready

for the next process, which is fermentation. The apartments in which the

process is conducted are called tun-rooms, and each contains a dozen large

tuns or vats ranged along the sides. The tuns are capable of holding 2000

gallons each. When the tuns are filled yeast is added to the wort, in order

to start the fermentation. In a short time carbonic acid gas is evolved, and

the liquid becomes covered with froth. The gas is so abundant that it

becomes dangerous to breathe over the tuns. Even after the vats have been

emptied the gas hangs about, and workmen entering them without first

ascertaining whether the fatal gas had disappeared have fallen victims to

their negligence. Great skill is required in determining the temperature to

which the wort should be reduced before adding the yeast. In summer it is

usual to cool it to some twenty degrees below the temperature of the tun-room,

while in winter it is worked at several degrees above the temperature of the

room. For the proper modification of the temperature the tuns are fitted

with tubes inside through which warm or cold water may be made to flow. The

pale amber colour and mild balsamic flavour which characterise Scotch beer

are owing in some degree to the low temperature at which it is fermented.

The process of fermentation is completed in from three to eight days, and

then the yeast is skimmed off and the beer "cleared" by being subjected to a

filtering and settling process, which removes all traces of fermentation.

That completes the manufacturing operations, and the beer is run into casks,

and either sent out to order or stored. The stock of porter is kept at the

brewery in great vats upwards of twenty feet in depth, but the ale is stored

at Roseburn. All varieties of beer, ale, and porter are made by processes

similar to those above described. The liquor may differ in strength

according to the quantity of water used, or in colour from the malt being

mom or less charred in drying.

Messrs Jeffrey's ale store at

Roseburn consists of two floors, each open throughout, and measuring 600

feet in length by 120 feet in width. A portion of the ground floor at one

end is devoted to the bottling of ales for export, which forms a

considerable item in the business of the firm. The remainder of the floor is

piled with five or six tiers of large store casks, in which the beer is

placed to mellow until required to be bottled or otherwise disposed of.

Cranes, tramways, &c., are provided for moving the casks; and in this, as in

the other parts of the establishment, hand labour is reduced to a minimum.

On the floor above the empty casks are kept. The bottling operations are

conducted with great expedition. The bottles arrive in crates, on being

taken from which they are thoroughly rinsed, placed on hand-trucks, and

brought forward to the bottlers. A boy sits in front of each

bottling-machine, which consists of a series of six taps arranged on the

syphon principle. Beginning at the left- hand side of the machine, he places

a bottle on each tap, and by the time he gets the sixth bottle attached the

first is full. Removing the full bottle he replaces it by an empty one, and

so on. The rapidity of his movements may be judged from the fact, that in

the course of a day of ten hours he fills 12,000 bottles, which is equal to

an average rate of twenty a-minute. For the service of each bottling-machine

there is a corking-machine, worked by a stout lad assisted by a boy; and a

staff of "wirers" and "foilers." The corking goes on at the same rate as the

filling; but as the wiring is a slower process, two nimble-fingered boys are

required to wire for each machine. The wiring is indispensable in the case

of beer intended for export. In some cases the cork and neck of the bottle

are covered with tinfoil, and in others by metallic capsules, which are

attached with great expedition. When all these operations are completed, the

bottles pass to the labeller, who, holding a bunch of gummed labels in one

hand, applies them with the other to the bottles, which are always moist

enough to make the paper adhere firmly. Thus got up, the bottles have rather

a gaudy appearance. As they are subjected to the successive operations

described, the bottles are passing from one side of the bottling-house to

the other; and as they leave the hands of the labellers, they reach the

packers. One set of men in this department twist a layer of straw round each

bottle, and another set pack the bottles into dryware barrels which contain

two or four dozen each. When the barrels are filled, they are taken charge

of by coopers, who put in the heads and make all secure. The barrels are

then rolled across the yard to a steam-hoist, by which they are elevated to

a platform on the railway siding belonging to the works, and thence taken to

the port of shipment.

Adjoining the stores is the

cooperage, which is on a scale coramensurate with the other departments of

the establishment. The beer-casks are made of seasoned oak, which is cut up

and shaped by steam-machines. The old system of firing has been abolished,

and after the staves are "set up,"—that is, arranged in a circular form

within a strong iron hoop, they are placed under a hollow iron cone, and

subjected to the action of steam, which speedily makes them pliable; and

while in that condition, they are "trussed" into form. Making large casks is

heavy work. The dryware barrels are of slighter construction and are hooped

with wood. Of these an immense number are turned out weekly.

Notwithstanding the numerous

mechanical appliances which exist in the various departments of Messrs

Jeffrey's establishments, they require the services of 250 men. |