|

IN the year 1735 M. de la

Condamine, who had been sent to South America by the French Government on a

scientific mission, communicated to the Academy of Sciences at Paris an

account of a resinous substance collected from certain kinds of trees, which

was used by the natives of Brazil for various purposes, such as making

boots, syringes, bottles, and vessels of different kinds for containing

liquors. M. Condamine stated that he had found the substance useful in

forming waterproof coverings, which were made by simply coating canvas with

the liquid as it exuded from the trees. That was the first intimation

received in Europe of the existence of caoutchouc, or, as it is more

commonly called, india-rubber, a material now extensively employed in the

arts. It was first brought to England about a century ago; and a treatise on

perspective drawing by Dr Priestley, published in London in 1770, contains

the earliest reference to its introduction and application to a useful

purpose in this country. Dr Priestley says,—" I have seen a substance

excellently adapted to the purpose of wiping from paper the marks of a

black-lead pencil. It must, therefore, be of singular use to those who

practise drawing. It is sold by Mr Nairne, mathematical instrument maker,

opposite the Royal Exchange. He sells a cubical piece of about half-an-inch

for three shillings, and he says it will last for several years." It was

from the property it possesses of removing pencil-marks that the name of

india-rubber was given to it. 11r Thomas Hancock, in his interesting

"Personal Narrative of the Origin and Progress of Caoutchouc or India-rubber

Manufactured in England," says that the substance came first into notice in

this country in the shape of bottles and animals, that it was sold at the

rate of a guinea an ounce, and was used for rubbing out pencil-marks. Up

till about the year 1820 it was applied to no other purpose.

Mr Hancock was the pioneer of

the manufacture of india-rubber, and it has been said truly that few

departments of manufacture have owed more to the ingenious contrivances of

one man than that of india-rubber owes to him. Mr Hancock became impressed

with the idea that a substance possessing such peculiar qualities as india-rubber

might be made available for other purposes than removing pencil-marks, and

in 1819 he began to make experiments. He first tried to dissolve the rubber,

expecting that it might become useful in a liquid form; but his attempts

were not satisfactory. He then took to cutting the rubber into thin bands,

and in 1820 obtained a patent for the application of these to articles of

dress in the form of braces, garters, &c. In cutting the rubber into

suitable shapes a large proportion had to be cast aside as useless parings.

Mr Hancock's next care was to devise means whereby such waste might be

avoided, and after several failures he succeeded in constructing a machine

which kneaded the scraps into a solid mass. This machine he called a "

masticator," apparently out of respect to the process by which schoolboys

reduce to the consistency of putty the India-rubber which they assert to be

an essential part of their academical equipment. The machine consisted of a

cylinder and casing, both furnished with spikes which tore the rubber into

shreds. During the operation sufficient heat was generated to cause the

shreds to amalgamate, and thus fresh blocks were formed. The masticator was

the first machine applied to the manufacture of india-rubber. From 1820 till

1847 Mr Hancock continued his researches with a wonderful degree of success,

and in that time obtained no fewer than fourteen patents. Almost

simultaneously with Mr Hancock, the late Mr George Macintosh, of Glasgow,

began to make experiments with india-rubber, and discovered that naphtha,

obtained from coal tar, had the power of dissolving the rubber. The solution

thus obtained he applied to cloth, which was thereby rendered waterproof. In

1824 he took out a patent for the manufacture of "waterproof," made by

cementing two folds of cloth together by means of the solution. Coats made

of that material, and bearing the name of the inventor, soon became famous.

Mr Macintosh formed a partnership in Manchester, and began to manufacture

waterproof garments, &c., on an extensive scale. The firm thus created still

exists, and their productions are widely known. Mr Hancock worked some of

his inventions in conjunction with Mr Macintosh, and ultimately entered the

partnership.

Encouraged by the success

which had attended the researches of Messrs Hancock and Macintosh, many

persons took to experimenting with india-rubber, and the result was a rapid

increase in the variety of its applications. Mechanicians hailed the rubber

as a sort of missing link in their code of materials for machine-making; and

such was the rage for introducing it, that it was frequently found in most

unsuitable positions. Now it forms an essential part of many machines, and

even the steam-engine has been rendered more perfect in its action by the

introduction of rubber valves and stuffing. The manufacture attracted

attention in America soon after it had been brought to a degree of

perfection in this country, and many novel applications of the substance

have had their origin in the United States. Mr Goodyear, an American

gentleman, has had a career in connection with the manufacture of india-rubber

somewhat akin to, though less brilliant, than that of Mr Hancock in England,

and both made independently one of the most wonderful discoveries bearing on

the treatment of caoutchouc. The great obstacles to a more extended use of

india-rubber were the clammy adhesiveness of the substance, its liability to

be affected by changes of temperature, and its sensitiveness to oil and

grease. Mr Hancock had tried to remove these obstacles, but without success,

until the year 1843, when he discovered the vulcanising process. In 1842 Mr

Goodyear sent an agent to this country offering for sale the secret of a

mode whereby the desired qualities could be imparted to the rubber; but as

no explanation of the process was allowed to be made until after purchase,

the agent returned without accomplishing his purpose. Mr Hancock saw some of

the specimens which had been sent over, and became convinced of the

practicability of changing the nature of the rubber. He thereupon renewed

his experiments, and in the course of a year had solved the problem, and

protected his process of vulcanising by a patent.

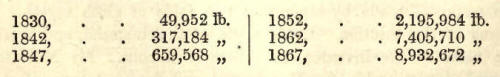

The increase which has taken

place in the consumption of india-rubber during the past forty years may be

seen from the following statement of the quantities imported into Britain in

various years:—

Granada, and the price ranges

from L.120 to L.260 a-ton. The value of the raw and manufactured rubber

exported annually now amounts to nearly L.1,000,000. Our best customers are

France and -- Australia.

Two of the largest and finest manufactories of india-rubber in the world are

situated in Edinburgh; and a description of these, and the operations

conducted in them, will illustrate the nature and capabilities of caoutchouc.

The establishments stand near each other on the bank of the Union Canal, on

the south-west side of the city, and belong respectively to the North

British Rubber Company and the Scottish Vulcanite Company (Limited).

In the year 1855 an

enterprising American gentleman brought to Edinburgh the machinery and

capital necessary for an india-rubber manufactory, and organised the North

British Rubber Company. Possession was acquired of the fine buildings known

as the Castle Mills, which had been erected at Fountainbridge as a silk

manufactory, and had long stood vacant, owing to the projectors not having

succeeded to their expectations. The establishment consists of two large

blocks of five floors each, and a number of subsidiary buildings.

The india-rubber arrives at

the manufactory in various shapes, according to the mode in which it is

collected by the natives of the different countries which produce it. The

finest qualities generally come in the shape of curiously formed bottles,

and the coarser kinds in roughly kneaded balls about four or five inches in

diameter. It is no unusual thing to find stones and other heavy substances

mixed with the rubber, for the collectors have learned the art of

adulteretion. The rubber is carefully examined with a view to the detection

of deleterious substances before it is subjected to the processes of

manufacture. After being softened by steeping in hot water, the rubber is

passed through the breaking and cleaning machines. The first of these

consists of two strongly-mounted iron cylinders, one of which is grooved

diagonally, while the other has a smooth surface. The balls of rubber are

fed in between the cylinders, which crush them out into thin pieces. These

pieces are then operated upon by a machine similar to the first, except that

both cylinders are smooth. The rubber is sent through again and again until

it is thoroughly broken and assumes the form of a web. If it be desired to

reduce it still further, the rubber is sent through a third set of rollers.

On examining the stuff as it comes from the breaking-machine, it is seen,

especially in the case of lower qualities, to contain a mixture of bark,

leaves, and other foreign matter; and it is to rid it of these that the

washing or cleaning machines are employed. Such is the adhesive nature of

the material, that it would be impossible to break or clean it in a dry

state, and consequently jets of water are made to flow on the rubber and

cylinders when the machines referred to are in operation. The water, besides

carrying off the impurities set free by the action of the rollers, causes

the rubber to assume a granulated appearance, and, under the pressure of the

cylinders, it is formed into a web. Simple though this process appears to

be, it is thoroughly effective in purifying the rubber. The webs of washed

rubber, which are made only three or four yards long, are taken to a

drying-room, where they are hung up in a warm atmosphere for several weeks.

From the drying-room the

rubber is taken to "the mill," which occupies two entire floors of the

principal block. The floors are covered by machines of the most powerful

construction; for the rubber is stubborn stuff, and submits only to a degree

of force that would destroy almost any other non-metallic substance. The

grinding-machines, to the operation of which the rubber is next subjected,

consist of two cylinders, one of which is slightly heated by steam, and the

webs formed by the washing-machines are kept revolving round and round the

cylinders until all appearance of granulation disappears and the stuff

becomes quite plastic. At this stage the rubber has incorporated with it

sulphur, or other chemical substances, which determine its ultimate

character, and is then made up into rolls of seven or eight pounds each.

There are steam-pipes through all the place, which prevent the rubber from

becoming hard again until it receives its final shape.

The further treatment of the

rubber depends on the purpose to which it is to be applied. To produce

articles of solid rubber, the material is rolled out into sheets of various

thicknesses, which are by subsequent operations brought into the desired

shape. The company do an extensive trade in shoes, and a considerable

portion of the machinery in the mill is devoted to the preparation of the

materials used in that department. Large quantities of waterproof fabric are

also made, and several machines are employed in. spreading the rubber on

cloth for that purpose. Some of the cloth used is silk, but more commonly

calico constitutes the base. It must be of even texture, and free from

knots; and in order to ensure that it is so, it is carefully examined and

picked before being placed on the spreading-machines. These machines consist

of a series of metal rollers, one of which takes up a supply of rubber and

transfers it to the cloth. No solvent is employed in this process, the

rubber being simply softened by the heated cylinders of the machines.

Driving- belts and hose are composed of layers of canvas impregnated with

rubber forced into the texture under immense pressure. The preparation of

the canvas is among the operations conducted in the mill.

There is great variety in the

goods produced; and as the appliances required in the production of each

kind are special, the manufactory is divided into a number of departments,

each with a distinct set of workpeople. One of the upper floors of the main

building is occupied by the shoemakers. This department is to the casual

visitor, perhaps, the most interesting in the establishment. Boots and shoes

of all sizes are made; but the articles most in demand are the galoshes

which ladies wear over their boots. Four classes of operatives are employed

in completing a shoe from the materials as they are sent in from the mill.

The first of these are the cutters, who shape the soles, uppers, &c., with

great rapidity. They spread out before them a web of prepared cloth, or a

sheet of rubber, and laying thereon a metal pattern, cut round it with a

sharp-pointed knife The linings are shaped in a different way. A number of

folds of the cloth are laid one over the other, and cut in a hydraulic press

by means of a die. All the work up to this stage is done by men. Ten pieces

of cloth and rubber are required to make one shoe, and as the parts are cut

out they are transferred to young women, who coat the edges of some of them

with a solution of india-rubber, and pass them on to the upmakers, all of

whom are young women. The rapidity with which the pieces are put together is

astonishing. The women sit at long tables, over the top of each of which is

an iron rack for holding the lasts. In order that they may withstand the

heat to which they are subjected while the shoes are being vulcanised, the

lasts are made of cast iron. Taking one of the lasts from the rack, the

operative rests it partly on the table and partly on her knees, and lays the

pieces on one after the other, rubbing each smooth with a small roller. No

stitching is required, the adhesive power of the rubber and solution being

sufficient to bind the parts together. An expert worker has turned out as

many as seventy pairs a-day; but at the usual rate of working from thirty to

forty pairs a-day may be taken as the average. The productive power of the

establishment is equal to making 7000 pairs a-day, or upwards of 2,000,000

pairs a-year. As the work goes on the shoes are collected by men and taken

to the varnishing shop, where they are coated with a liquid which gives them

a smooth and glossy appearance. They are then arranged in a travelling

framework of iron and placed in the vulcanising chamber or stove, from which

they are brought forth ten or twelve hours after ready for use.

On another floor are the

makers of coats, leggings, cushions, bags, &c. The drab or cream-coloured

overcoats for India are the finest articles of clothing made in the

establishment, and for lightness, durability, and elegance are unsurpassed.

The cloth is cut by men, and the parts are put together by young women, who

employ a mode of joining them that is more expeditious than the

sewing-machine. All the seams are formed by cementing the edges with

"solution," and then overlaying them with a fillet of rubber. When the coats

are completed they are placed in the vulcanising chamber, and there undergo

a change which prevents heat or cold from having any effect upon them. As

made by the old process, india-rubber waterproof coats lost their elasticity

in frost, and got so soft under the influence of heat that it was no unusual

thing to find that a coat which had been folded away during the summer had

actually melted and become useless by the softened surfaces adhering

together. No such mishap can befall a coat made by the process adopted by

the North British Rubber Company. The mode in which leggings,

travelling-bags, and other articles of that kind are made need not be

described, as it closely resembles that by which shoes and overcoats are

produced.

The mechanical applications

of india-rubber are numerous and varied, and the importance of the material

in this respect is daily increasing. Its use in the form of carriage-springs

was patented so early as 18223 but little farther progress in that direction

was made until about ten or fifteen years ago, when rubber began to be

employed extensively in the shape of tubes, springs, washers, driving-

belts, valves, tires for wheels, &c., the making of which now constitutes an

important branch of manufacture. The North British Rubber Company have paid

much attention to the development of this section of their trade; and the

mechanical department occupies one of the main blocks of their factory. As

already stated, the base of hose-pipes and driving-belts is composed of

canvas impregnated with rubber. Though known as india-rubber belts, the

chief part of these articles consists of canvas, the quantity of rubber used

being merely what is sufficient to fill up the texture of the cloth, make

the respective folds adhere firmly, and form a shield or wrapper to confine

the whole and protect it from moisture. The canvas having been pre¬. pared

in the mill is cut into stripes of the desired width, and two, three, or

four stripes are laid one over the other, and made to adhere by being passed

between pressing rollers. The shield or envelope is then put on. It consists

of canvas similar to what constitutes the core, but one side of it bears a

strong coating of rubber. The wrapping completely surrounds the core, and

the edges of it are firmly united by an overlapping fillet fixed with

solution. The completed belt looks like a piece of solid rubber, but its

strength is infinitely greater—in fact, a belt made of rubber alone would be

almost useless in transmitting power on account of its elasticity. The belts

are made in lengths of 300 feet, and of various breadths and thicknesses,

but there is no practical limit to the dimensions. Hose and other pipes are

made in a somewhat similar way. They are formed on mandrels, and have a

coating of rubber both inside and out. A pipe one inch in diameter, composed

of four folds of canvas with the usual proportion of rubber, will bear a

pressure equal to 1000 lb. on the square inch. Suction pipes, which have to

be so constructed as to withstand the atmospheric pressure, have a layer of

wire inserted into them. The wire is spun into a spiral form on a machine,

and the tubemaker, after covering the mandrel with a rubber lining, puts on

the wire and fills up the interstices with soft rubber. The canvas and

wrapper are then applied. The vulcanising ingredients having been

incorporated with the rubber in the mill, all that now remains to be done in

order to complete the work is to place it in an oven, so that the heat and

cold resisting powers of the rubber may be developed. Among the uses to

which india-rubber has been recently applied may be mentioned the formation

of rollers for lithographic and calico-printers and paper-makers, insulators

for telegraphs, and cells for galvanic batteries, all of which purposes it

suits exceedingly well. The other articles produced in the mechanical

department are too numerous and their purposes too varied for enumeration;

but one piece of work merits notice on account of its novelty and

unprecedented size. Mention has been made of the road steamer invented by Mr

R. W. Thomson, of Edinburgh, and the new application of india-rubber

embodied therein. The peculiarity of Mr Thomson's carriage is that the tires

of the wheels are composed of huge rings of vulcanised rubber. The tires

were made by the North British Rubber Company, and are the largest pieces of

the material ever manufactured, each tire weighing 750 lb.

India-rubber is admirably

suited for door-mats, which are made by piercing thick sheets or slabs of

rubber in geometrical patterns. A new variety of mat has just been produced,

into which the name or monogram of the owner is introduced. The forms in

which india-rubber is most widely known are those of elastic-cords, ribbons,

and webs, and in that department of the manufacture a number of hands are

employed at the Castle Mills. The rubber is cut by machinery into threads,

which are then, having been deprived of their elasticity by a simple

process, either braided singly or woven with cotton and silk yarns in a

ribbon-loom. The looms in the weaving shop are each capable of weaving eight

ribbons of elastic at a time. The braiding-machines are beautiful pieces of

mechanism. The thread of rubber is held in a vertical position, while a

series of bobbins move round it, and round each other in an exceedingly

curious way. Thus the rubber is enclosed in a casing of silk or cotton,

which protects it from abrasion, and renders it applicable to a thousand

useful purposes.

The company employ 600

workpeople in their establishment, but in the preparation of the cloth,

thread, &c., used in the manufacture, as many more are employed in an

indirect way. The health and comfort of the operatives are carefully

provided for. All the women are paid by piece. In no department can it be

said that the labour is heavy, and the work assigned to the women is

peculiarly suited to them.

The Scottish Vulcanite

Company (Limited) was formed in 1861 by a number of shareholders in the

North British Rubber Company, but the two concerns are quite distinct in

every other respect. The company began operations on a small scale under an

American patent, and with machinery and instructors brought from America.

They built a factory on the bank of the Union Canal near that of the North

British Rubber Company, and their machinery was started in 1862. In

consequence of the novel nature of the work, many difficulties were

encountered at the commencement. A set of workpeople had to be trained, and

that was found to be a slow operation, entailing the waste of much material.

Under admirable management the company overcame all preliminary

difficulties. Their original factory has already had a fourfold increase,

and they now employ about 500 persons. The factory consists of a large

central block 230 feet in length, and seven smaller detached buildings. The

main block has four floors, and the others two floors each. A beautiful

engine of 120 horse power, erected in one of the most elegant of

engine-rooms, supplies the motive power. Everything required for upholding

the establishment is made on the premises by the workmen of the company.

The machines used in

breaking, washing, and kneading the rubber are similar to those employed in

the North British Company's factory. Only the best quality of rubber is

used, and the first process peculiar to the establishment is the conversion

of it into "vulcanite" by incorporating with it certain chemical substances,

and submitting it to the action of heat in an oven. After the chemicals are

put in, the rubber is rolled out into sheets about three yards long, half a

yard wide, and of various thicknesses. The sheets are laid on canvas-covered

frames or trays, which are piled one above the other until the oven is

filled. When the rubber is removed from the oven, it is found to have

undergone a complete change. Each sheet is then cut into two, placed between

metal plates, and subjected to a greater degree of heat. The effect of this

treatment is to convert the rubber—which, when it went into the oven in the

first instance, bore a close resemblance to putty—into a hard, black,

glistening substance, applicable to a great variety of purposes. The change

is a very mysterious one; indeed, in the whole range of chemistry there is

scarcely a more wonderful thing than the production of the hard horny

substance called "vulcanite" from elements which, in their unmixed state,

are so unlike it. The idea of producing such a substance was one that could

not have been arrived at by any amount of reasoning on the known properties

of caoutchouc and the other ingredients; and unless it had been brought

about by accident, it is probable that vulcanite would not yet have been

known.

The story of Mr Goodyear, the

American manufacturer who invented the process of vulcanisation, is very

interesting. After having brought the manufacture of india-rubber to a

degree of perfection, he undertook to supply india-rubber mail-bags to the

Government. As the substance was then treated, it was not suited for that

purpose, and the bags became soft, and failed altogether in a short time.

The result was most disastrous to the manufacturer, who was forced to

abandon the trade. Mr Goodyear did not despair of discovering a mode of so

treating the rubber that it would not be readily affected by heat. He tried

to attain his object by mixing certain substances with the rubber. He was in

his abandoned factory one day, along with several friends; and after showing

them the hopeless product of his experiments, he stood near a stove while he

discussed matters with them. He retained in his hand the compound of rubber,

&c., which he playfully held against the stove, little dreaming that he was

making an experiment that would render his name famous. On removing the

rubber, he observed that it had become charred, and was hard and tough like

leather. Further experiments completed the discovery, and the fortune of Mr

Goodyear took a sudden turn. As already stated, Mr Hancock of London

discovered Mr Goodyear's secret, and patented it; but there is no doubt that

the vulcanising ingredients were suggested to Mr Hancock by discovering

traces of them in some specimens of india-rubber which had been vulcanised

by Mr Goodyear.

There are three departments

in the Vulcanite Company's factory, which produce respectively combs,

jewellery, and miscellaneous articles. In the comb department, the first

operation is to convert the sheets of vulcanite into pieces of suitable

size, which is expeditiously done by a cutting-machine. The pieces intended

for the finest quality of dressing-combs are placed in heated moulds, and

have a plain or ornamental rib raised on the back part, which at once

increases the strength and improves the appearance of the combs. The slips

of vulcanite so formed are then taken to the cutting-room—a large apartment,

around which are arranged a number of beautiful little machines for forming

the teeth of the combs. Each slip of vulcanite makes two combs, the teeth of

one being cut out from between the teeth of the other. The machines are

fitted with metallic tables, kept hot by branches from a steam-pipe which

passes round the room. A pile of slips are deposited on the heated table,

and are thus softened, the operative withdrawing the lowest slip, or that

which is most pliable each time he supplies the machine. One slip is

operated on at a time, and is laid on a travelling plate, which moves

forward under a pair of cutters. The cutters rise and fall with great

rapidity, and with the assistance of an expert workman each machine will

produce from 130 to 200 dozen combs a-day. When the slips are withdrawn from

the machine, the operative, by a dexterous pull, separates the two combs,

which, in the soft state to which the material has been reduced, appear

utterly useless, looking indeed as if they were made of leather, the teeth

being twisted in all directions. A moment's pressure on the hot plate makes

all right again; and when the combs cool, they are perfectly straight. Such

is the minuteness of the division of labour in the establishment, that after

the cutting is completed, the combs have to pass through a dozen departments

before they are ready to be sent out. It is not necessary to follow them

through all these, but one or two of the principal operations to which they

are subjected may be mentioned. The cutting-machine gives a wedge-like point

to the teeth; but it is necessary that they should also be tapered on the

outer surface. For that purpose the combs are sent to the grinders, who

reduce them to the desired shape on a stone. On examining a comb, it will be

seen that the teeth are sharpened towards the edge, so that they have a

diamond shaped section. The operation by which they are thus sharpened is

called "grailing," and is performed by hand, the workmen using a broad file,

which they apply with astonishing rapidity and certainty. The backs and ends

are rounded on the grinding-stone, and then the combs are "buffed," to give

them a smooth surface. They are next washed, dried, and polished, after

which they are sent into the packing-room to be examined and packed up. A

cheap and strong kind of comb is made with a brass or white metal mounting

on the back. The metal is shaped by means of a die, and is attached to the

comb by compression and by being clenched at the ends. Fine combs—or, as

they are vulgarly called in Scotland, "sma'-teeth combs"—are made in a

different way. The vulcanite is formed into plates the size of a comb,

rounded at the ends, and thinned towards the edges. The plates are then

placed singly into a machine, which cuts the teeth. The department devoted

to this branch of the manufacture is situated in an upper room, open only to

privileged visitors, as there are certain specialties connected with it

which the company have introduced at much cost, and consequently desire to

retain to themselves. It may be mentioned, however, that the teeth-cutting

machines, of which about fifty are in use, are exceedingly beautiful and

ingenious. They are arranged on a long table, and each does not occupy more

than the space of one square foot. Each machine consists of two parts—a

small circular saw and a travelling carriage, in which the plate of

vulcanite is fixed. The carriage has three motions—one forward towards the

saw, one backward, and the other from left to right. When a plate is

inserted and the machine started, the carriage advances, and one interspace

is formed by the saw; it then retires, moves the thick-ness of a tooth to

the right, advances again to the saw, and so on. The machine is very rapid

in its movements, and can cut the teeth on both sides of a four-inch comb in

two minutes. A couple of women keep the machines supplied with plates. The

saws, which are little more than two inches in diameter, are sharpened by a

self- acting machine peculiar to the establishment. All the machines are

driven by steam. Besides dressing and fine combs, a variety of others are

made, much taste and ingenuity being expended on ladies' back combs, which

are mounted with metal, glass, porcelain, or ornamented with carving, &c.,

in vulcanite. The company was created chiefly for the purpose of making

combs, and that department is the most important in their establishment. No

fewer than 24,000 combs are made every day, or about 7,500,000 a-year.

Vulcanite is the only

material that has successfully competed with jet for making black jewellery.

In appearance it closely resembles jet, and has the advantage of being

stronger and cheaper. Dining the past four or five years vulcanite jewellery

has attained immense popularity, and the demand for it is rapidly

increasing. Owing to the brittle nature of jet it is difficult to work, and

articles made of it will always be costly and delicate. Vulcanite, on the

other hand, may be readily moulded, carved, or stamped into almost any form.

Among the articles of jewellery made of it are ladies' long and Albert

chains, necklets, bracelets, gauntlets, buckles, and coronets. The chains

are composed of variously shaped links, but the mode in which they are made

is alike in all cases. The vulcanite is first cut into slips about eighteen

inches in length and one inch in width. It is then taken to a room in which

are a number of punching machines worked by girls. The links are punched out

at two operations, the first making the opening in the centre, and the

second cutting out the circumference. The punched edges are rough; and in

order to smooth and polish them the links, after being fixed on an iron rod,

are ground down to a standard size, and polished on the "buff" " wheel. They

are then ready for being put together, for which purpose they are

transferred to women who sit at benches fitted with hot plates. After lying

for a few minutes on the plate, the alternate links are cut open at one end

with a knife, and these are readily opened and slipped into their

neighbours. Many ear-rings are made by combining links in. various ways;

links are also introduced into some kinds of back combs, bracelets, &c.

In the miscellaneous goods'

department a great variety of articles are made. Owing to the power which

vulcanite possesses of resisting the action of acids, it is of much value in

the construction of surgical and chemical instruments, and is now being

extensively applied in the manufacture of tubes, syringes, flasks, stoppers,

&c. A large trade is also done in making vulcanite cells for galvanic

batteries. Knife-handles, card-trays, neckties, girdles, and gauntlets are

among the other products of the factory. The vulcanite knife- handles are

exceedingly pretty, and are superior to ivory, bone, horn, or whalebone

handles, in that they cannot be detached from the blade unless they be

smashed off, and that they are neither split nor discoloured by immersion in

hot water. The card-trays are chiefly made up of thin sheets of vulcanite

ornamented with designs in fretwork. Among the greatest novelties are the

neckties, which look exactly like silk, the texture being closely imitated

by some peculiar process. They are made up in a variety of styles. There

appears to be no limit to the uses to which this wonderful substance may be

put; and were the raw material more abundant, and consequently cheaper, it

would be employed as a substitute for wood, paper-mache, and like materials,

in the construction of many articles of ornament and use in the shape of

furniture.

In a manufactory of this kind

the making of packing-boxes constitutes an important department. In the shop

in which the paper boxes are made seventy young women are employed, and they

are aided by a number of beautiful cutting and moulding machines. The boxes

and goods are brought together in the warehouse, where they are made ready

for sending out.

All the departments of the

factory are kept thoroughly clean; and the rooms are lofty, well lighted,

and well ventilated. For the convenience of the women who reside at a

distance, there is a large dining-hall, comfortably furnished and heated by

steam-pipes. Nearly all the operatives are paid by piece, the women earning

from 10s. to 14s. a-week for 57½ hours' work. Some of the men earn a high

rate of wages, a journeyman comb-cutter making about L.2 a-week when

employed on certain kinds of work. It is a fact worthy of mention, that the

men who are employed in mixing the chemicals with the rubber, and in

conducting other operations in vulcanising, are peculiarly healthy, and

never suffer from diseases of an epidemic type. |