|

COTTON-WOOL has been known in

Britain for at least six hundred years; but for four centuries the only use

to which it was put was the formation of candle-wicks. At least no mention

occurs of the manufacture of the fibre into cloth until 1641. Mr Baines, the

historian of the cotton trade, has recorded his belief that the art of

spinning and weaving cotton was brought into England by the Flemish

refugees, in the end of the sixteenth century. Others are of opinion that

the art slowly spread from its birthplace in India, where it has been

practised from time immemorial—first into Arabia, then westward through

Spain to Britain. The first authentic reference to the manufacture of cotton

in this country occurs in "The Treasure of Traffic," a small work published

in 1641, and is as follows:—"The town of Manchester, in Lancashire, must be

also herein remembered, and worthily, for their encouragement, commended,

who buy the yarne of the Irish in great quantity; and weaving it, return the

same again into Ireland to sell. Neither doth their industry rest here, for

they buy cotton-wool in London, that comes first from Cyprus and Smyrna, and

at home worke the same, and perfect it into fustians, vermilions, dimities,

and other such stuffes, and then return it to London, where the same is

vented and sold, and not seldom sent into forrain parts." No attempt appears

to have been made at that time to imitate the fine cotton fabrics of India,

which were imported in large quantities by the English and Dutch East India

Companies. The muslins, chintzes, and calicoes of the East became extremely

fashionable for ladies and children's dresses. In 1678 this import trade had

become so extensive that an outcry was raised against it, on account of the

prejudicial effect it had on the woollen and silk manufactures already

established in England. Public opinion found vent in numerous pamphlets,

some of which presented extraordinary views of political economy. The home

cotton trade was too insignificant then to be recognised as at all

interfering with the other textile manufactures, and no mention was made of

it by the pamphleteers. The author of a brochure entitled "The Naked Truth,

in an Essay upon Trade," published in 1696, says:—"The commodities that we

chiefly receive from the East Indies are calicoes, muslins, Indian wrought

silks, pepper, saltpetre, indigo, &c. The advantage of the company is

chiefly in their muslin and Indian silks (a great value in these commodities

being comprehended in a small bulk), and these are becoming the general wear

in England. Fashion is truly termed a witch—the dearer and scarcer any

commodity, the more the mode. Thirty shillings a-yard for muslins, and only

the shadow of a commodity when procured !" The Government were at length

induced to interfere to prohibit the use of Indian goods. An Act of

Parliament was passed in 1700, which forbade the introduction of Indian silk

and printed calicoes for domestic use, either in apparel or furniture, under

a penalty of L.200 on the weaver or seller. So strong was the desire to

possess the forbidden goods, that an extensive system of smuggling sprang

up, and further measures were necessary in order to accomplish the purposes

of the first Act.

The manufacture of cotton was

carried on in every quarter of the globe—its chief seats in Europe being

Italy, Spain, Turkey, Bavaria, Saxony, Prussia, and the Low Countries—before

it was introduced into England. But though thus almost the last to take up

the trade, no country has done more than England to perfect the manufacture,

nor has any one profited more by it. The cotton manufacture is the staple

trade of Britain, employing about a million of the inhabitants, and yielding

in the form of wages and profits the immense sum of L.60,000,000 a-year.

Cotton cloth is the cheapest article of clothing manufactured, and Britain

is the chief source from which the markets of most countries are supplied.

Such being the case, a brief sketch of the general history of the cotton

manufacture may be properly given here, as a prelude to a notice of the

introduction and development of the trade in Scotland.

The first mention of cotton

as an article of import occurs in the Customs' books for 1697. In that year

1,976,359 lb. of cotton-wool were imported into Britain; and the cotton

goods exported were officially valued at L.5915. The quantity of cotton-wool

imported showed rather a decrease in succeeding years until 1746, when it

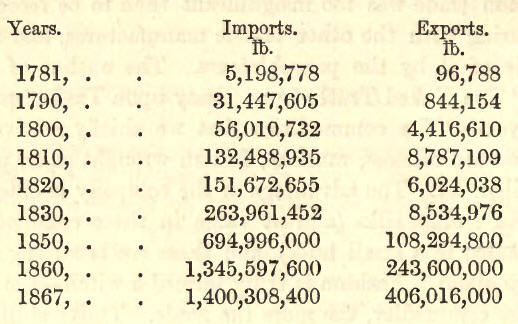

suddenly leaped up to 2,264,868 lb. The following table of the imports and

exports for a number of years will show how the trade has increased:—

The cotton trade owes its

marvellous development to a variety of mechanical contrivances, the history

of which forms one of the most interesting chapters in the records of

inventions. The machines used in the textile manufactures generally were of

a primitive kind till past the middle of last century. In 1760 the Society

of Arts offered. a premium for the greatest improvement in the common

spinning-wheel, which, excepting the distaff and spindle, was the only

apparatus then known by which a thread could be formed. The society

afterwards offered a prize of L.100 for the invention of a machine that

would spin six threads of wool, cotton, flax, or silk at the same time. This

roused to action the minds of many mechanicians, and the result was a

triumphant success. When the demand for cotton cloth increased beyond the

powers of production, the price rose considerably, and weaving became a

favourite occupation; but the spinners were not equal to the task of keeping

all the weavers employed. The trade was then a domestic one, the husband

generally weaving the yarn spun by his wife, and both being assisted by

their children. Up till 1773 cotton was never used alone in the formation of

cloth. The yarn was not considered to be strong enough for warp, and

accordingly linen yarns, procured chiefly from Ireland and Germany, were

used for that portion of the fabric. The merchant supplied the linen yarn,

with a certain proportion of raw cotton, to the weaver; and if the latter

had not a family who could spin the cotton, he employed other persons to do

so. It is stated to have been no uncommon thing for a weaver to walk three

or four miles in a morning, and call on five or six spinners, before he

could collect weft sufficient to serve him for the remainder of the day; and

when he wished to weave a piece in a shorter time than usual, a new ribbon

or a gown was necessary to quicken the exertions of the spinner.

The productive power of the loom was doubled by the invention of the "fly

shuttle," and as that happened at the time it was found most difficult to

obtain yarn, Mr Kay, the inventor, was subjected to great persecution by the

weavers, who feared that their occupation was endangered by the invention,

and the result was that he had to leave the country. A dozen years before

the Society of Arts moved in the matter, a machine for spinning by rollers

was invented by Mr John Wyatt, and its practicability successfully

demonstrated; but. Mr Wyatt shared the too common lot of inventors, and

failed to reap the fruits of his ingenuity. His memory will be preserved,

however, as the inventor of the primary principle of a most important part

of the spinning-machinery now in use throughout the world. But the chief

honours in machine spinning belong to Hargreaves, the inventor of the

spinning-jenny; to Arkwright, the inventor of the spinning-frame; and to

Crompton, who, in 1779, combined the action of both machines in the "mule

jenny." Though the increase of spinning power, so necessary and so much

desired, was thus provided, the work- people offered great opposition to the

introduction of the new machines.

In 1779 a mob rose and

scoured the country for several miles round Blackburn, demolishing the

jennies, and with them the carding- engines, and every machine set in motion

by horses or by water. It would appear that the rioters admitted the jennies

containing twenty spindles to be useful, and they spared all such; but those

which contained more than twenty spindles were either destroyed or cut down

to the standard which the mob had fixed. The sentiments and actions of the

rioters were sympathised with and participated in by the middle and upper

classes, who, failing to perceive the tendency of inventions for improving

and cheapening the manufacture to cause an extended demand, and thereby give

employment to more hands than were in the first instance superseded, became

alarmed lest they should be subjected to increased taxation for the support

of the workmen who would be thrown idle by the use of machinery. Spinners

and other capitalists were driven from the locality in which the riots took

place, the trade became almost extinct, and it was many years before

cotton-spinning was resumed at Blackburn. Mr Peel, the great-grandfather of

the present Sir Robert Peel, was among the sufferers at the hands of the

rioters, the machinery of his cotton-spinning mill having been thrown into a

river, and his personal safety threatened. A large mill built by Arkwright

at Birkacre, near Morley, was destroyed by a mob in the presence of a

powerful body of military and police, who failed to act in consequence of

not being called upon to do so by the civil authorities.

Contrary to the absurd

notions and desire of the workpeople, the spinning machines were generally

adopted by manufacturers, and results were achieved which convinced

everybody of the value of the inventions. Having succeeded in overcoming the

prejudices of their operatives, the manufacturers began to entertain

feelings of jealousy towards each other. The spirit which prevailed is

described in the following extract from "Baines' History of the Cotton

Manufacture:"—"This period of high intellectual excitement and successful

effort would be contemplated with more pleasure, if there had not at the

same time been displayed the workings of an insatiable cupidity and sordid

jealousy, which remorselessly snatched from genius the fruit of its

creations, and even proscribed the men to whom the manufacture was most

deeply indebted. Ignorance on the one hand, and cupidity on the other,

combined to rob inventors of their reward. Arkwright, though the most

successful of his class, had to encounter the animosity of his

fellow-manufacturers in various forms. Those in Lancashire refused to buy

his yarns, though superior to all others, and actually combined to

discountenance a new branch of their own manufacture, because he was the

first to introduce it. He has related the difficulties with which he had to

contend in his `Case.' `It was not,' he said, till upwards of five years had

elapsed ,after obtaining his first patent, and more than L.12,000 had been

expended in machinery and buildings, that any profit accrued to .himself and

partners.' The most excellent yarn or twist was produced; notwithstanding

which, the proprietors found great difficulty to introduce it into public

use. A very heavy and valuable stock, .in consequence of these difficulties,

lay upon their hands; inconveniences and disadvantages of no small

consideration followed. Whatever were the motives which induced the

rejection of it, they were thereby necessarily driven to attempt, by their

own strength and ability, the manufacture of the yarn. Their first trial was

in weaving it into stockings, which succeeded; and soon established the

manufacture of calicoes, which promises to be one of the first manufactures

in this kingdom. Another still more formidable difficulty arose: the orders

for goods which they had received, being considerable, were unexpectedly

countermanded, the officers of excise refusing to let them pass at the usual

duty of 3d. per yard, insisting on the additional duty of 3d. per yard, as

being calicoes, though manufactured in England; besides, these calicoes,

when printed, were prohibited. By this unforeseen obstruction, a very

considerable and very valuable stock of calicoes accumulated. An application

to the Commissioners of Excise was attended with no success; the

proprietors, therefore, had no resource but to ask relief of the

Legislature, which, after much money expended, and against a strong

opposition of the manufacturers in Lancashire, they obtained.'"

While the spinning machinery

was being brought to perfection, it became evident that something would

require to be done to improve the preliminary process of carding the cotton.

Lewis Paul, who was the patentee of Wyatt's invention for spinning by

rollers, had so early as 1748 taken out a patent for a cylinder

carding-machine, the various parts of which bore a close resemblance to the

carding- engines at present in use. Paul's machine was defective in many

ways, however, and little progress was made towards producing a really

efficient mechanical carder until Arkwright devoted his ingenious mind to

the subject. On the 16th December 1775 the great mechanician took out a

patent for a series of apparatus, comprising the carding, drawing, and

roving machines. These were so decidedly advantageous that they were at once

adopted, and the effect on the trade was almost magical. The factory system,

which, except to a small extent in the silk manufacture, was then unknown in

England, became established throughout the country; and the mechanism

devised for spinning cotton was applied to the spinning of wool, flax, &c.,

so that all the textile manufactures of the country received a gigantic

impulse from the introduction of machinery to supersede hand labour.

Arkwright prospered in business, but he was not allowed to enjoy an

undisputed title to his inventions. His success stimulated the jealousy of

his fellow-manufacturers; and as there was a belief prevalent in Manchester

that he was not really the author of the inventions for which he claimed

patents, several persons ventured to set up machines similar to his without

obtaining a license. Aia association of Lancashire spinners was formed to

defend the actions raised by him against the persons who infringed his

patents. On various pretexts his patent for preparing-machines was set aside

in 1785. He resented the treatment to which he had been subjected by his

competitors in the trade, and exerted himself to raise up in Scotland a

successful rivalry to Lancashire. With that view he favoured the Scotch

spinners as much as possible, and formed a partnership with Mr David Dale of

Lanark Mills.

Though the invention of the

spinning-frame, spinning-jenny, and carding-engines did much to advance the

manufacture of cotton, something was left to be desired. The water-frame

produced suitable yarn for warp, and the jenny made excellent weft; but they

were not capable of making the finer qualities of yarn. In 1779 a weaver

named Samuel Crompton succeeded in producing a machine which combined the

chief features of the water-frame and spinning- jenny, and was capable of

producing yarns suitable for muslins. Owing to its hybrid origin, the new

machine was called the "spinning mule." Crompton toiled at his loom in an

old mansion-house, and spent all his spare time and money in working out his

invention. He was of a retiring disposition; and when the machine was

completed he wished, in his own words, "to enjoy his little invention to

himself." The yarn he produced was so superior in quality that persons from

all quarters sought him out in order to ascertain how he spun it. He found

that he could not retain the secret of his invention, nor was he rich enough

to patent it, so he gave it to the public on condition that a petty sum

(L.60) should be raised by subcription. He subsequently got a grant of

L.5000 from Parliament. The next step in advance was made by Mr Kelly of

Lanark Mills, who in 1790 applied water power to work the mill, and two

years later communicated a self-acting motion to the mule. Mr Buchanan, of

the Catrine Cotton Works, also invented a self-acting mule. Many minor

improvements have since been made, and as showing the degree of perfection

that has been attained, it may be mentioned that the spinning-mule has been

found capable of forming, from one pound weight of cotton, a thread 950

miles in length, whereas the water-frame of Arkwright made only forty hanks

to the pound, or a length of nineteen miles. A pound of the finest cotton

yarn may be worked into lace worth L.250.

Prior to the year 1790 the

only motive power applied to the machinery of the cotton mills was water,

and mills could be erected only where an abundant supply of that element was

available. Lancashire owes its early and extensive connection with the

cotton trade mainly to the fact that the county is intersected by a large

number of streams which descend rapidly from the hills in the hundreds of

Blackburn and Salford. Thirty years ago there were on the river Irwell alone

300 mills propelled by water. When all the available water power was taken

up in any locality, there was a bar to any increase or extension of the

mills; and were no other motive power available, the cotton trade would be

distributed more generally over the country. But when the manufacturers were

beginning to realise the disadvantages of depending on the water power,

James Watt was completing his improvements on the steam- engine. Watt's

engine found favour in the eyes of the cotton manufacturers, and came into

general use. Supplied with a motive agent of unlimited and inexhaustible

power, which could be made available in almost any locality, the

manufacturers felt their position to be much improved. It was no longer

necessary for one proposing to build a mill to range the country in search

of a waterfall of sufficient strength to keep his machinery going, and,

having found such—it might be far away from any centre of population—to

convey thither not only the appliances and material necessary to carry on

the work, but to induce an adequate number of workpeople to take up their

abode in the neighbourhood of the mill. The steam- engine enabled him to set

up his mill in the midst of the people.

When the spinning machinery

was brought to a degree of perfection, it was found that a good deal more

yarn was produced than the weavers could use up, and a large quantity was

exported. Attempts to construct a machine for weaving had been made first in

1678 and again in 1765; but they were unsuccessful, and the fact of their

having been made was all but forgotten. In the year 1784 a company of

gentlemen had met at Matlock, and, some of them being manufacturers from

Manchester, conversation naturally turned on the inventions of Arkwright.

The Rev. Dr Cartwright, of Kent, who was present, remarked that Arkwright,

having completed his spinning machines, would next require to invent

machinery for weaving. The other gentlemen expressed a unanimous opinion

that such a thing was impracticable. What followed is related by Dr

Cartwright in a letter which he wrote to Mr Bannatyne of Glasgow. "In

defence of this opinion," he says, "they adduced arguments which I certainly

was incompetent to answer, or even to comprehend, being totally ignorant of

the subject, having never at that time seen a person weave. I controverted,

however, the impracticability of the thing by remarking, that there had

lately been exhibited in London an automaton figure which played at chess.

Now you will not assert, gentlemen, said I, that it is more difficult to

construct a machine that shall weave than one which shall make all the

variety of moves which are required in that complicated game. Some little

time afterwards I employed a carpenter and smith to carry my ideas into

effect. As soon as the machine was finished, I got a weaver to put in the

warp, which was of such materials as sail-cloth is usually made. To my great

delight a piece of cloth, such as it was, was the produce. As I had never

before turned my thoughts to anything mechanical, either in theory or

practice, nor had ever seen a loom at work, or knew anything of its

construction, you will readily suppose that my first loom was a most rude

piece of machinery. The warp was placed perpendicularly, the reed fell with

the weight of at least half a hundredweight, and the springs which threw the

shuttle were strong enough to have thrown a Congreve rocket. In short, it

required the strength of two powerful men to work the machine at a slow

rate, and only for a short time. Conceiving, in my great simplicity, that I

had accomplished all that was required, I then secured what I thought a most

valuable property by patent, 4th April 1785. This being done, I then

condescended to see how other people wove; and you will guess my

astonishment when I compared their easy mode of operation with mine.

Availing myself, however, of what I then saw, I made a loom in its general

principles nearly as they are now made." Dr Cartwright in 1809 received a

grant of L.10,000 for his ingenious invention. Other inventors entered the

field, and, while some devoted their attention to improving on Dr

Cartwright's loom, others set themselves to construct an entirely novel

machine. Reference has been made to some of those inventors in dealing with

the woollen manufactures.

It had been the custom in

hand-loom weaving to "dress" the warp in the loom, for which purpose

frequent stoppages had to be made. In order to keep the power-looms going

steadily, a man was required to dress the warp while another attended to the

weaving. The extra hand consumed all the profits of the improved loom; and

the next thing demanded was an apparatus that would dispense with his

services. Mr William Radcliffe, cotton manufacturer, of Stockton, set to

himself the task of overcoming the difficulty. On the 2d January 1802 he

shut himself up in his mill along with a number of weavers and mechanics,

resolved to produce some improvement. After two years of experiments the

dressing-machine was produced, and by its use the power-loom was rendered

fully efficient. The power-loom most commonly employed at present was

invented by Mr Horrocks, of Stockport, between the years 1803 and 1810. It

is constructed entirely of iron, and is a neat, compact, and simple machine,

moving with great rapidity, and occupying little space.

A few facts will illustrate

the effect which the inventions mentioned have had on the cotton trade. In

1786 the yarn known in the trade as No. 100 sold at L.1, 18s. a pound. Seven

years afterwards the price had fallen to 15s. ld. In 1800 the price was 9s.

5d., and in 1832, 2s. lid. The cost price of a piece of calico was L.1, 3s.

101d. in 1814. In 1822 the same could be made for 8s. 11d., and in 1832 for

5s. 101d. The official value of the cotton goods exported from Britain in

1720 was L.16,200; in 1780, L.355,060; in 1795, L.2,433,331; in 1810,

L.17,898,519; and in 1830, L.35,395,400. The value of the raw and

manufactured cotton exported from Britain at present is about L.80,000,000

a-year.

The wonderful inventions of

Arkwright and others, and the impulse that these gave to the cotton trade,

did not escape the notice of Scotch manufacturers; but it would appear that,

though they entered into the manufacture of cotton with great spirit and

enterprise after it had been carried north of the Tweed, the credit of

introducing it belongs to Englishmen. The first cotton mill in Scotland was

built at Rothesay in the year 1778 by an English company, but was not long

in being acquired by Mr David Dale, who became one of the most extensive

cotton manufacturers in the country. The mill was of small extent, and in

the present day would be regarded as an almost insignificant concern; but it

was the nucleus of one of the most important branches of industry that has

ever been carried on in • Scotland. The germ planted by English hands had a

rapid growth; and, before the Rothesay mill was sixty years old, there were

nearly two hundred cotton factories in Scotland Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire

were chosen as the chief seats of the trade, partly on account of the

abundant supply of water power available, and partly because persons with

the capital and enterprise required to carry on the new trade were more

numerous in the west, while many of them had previously been engaged in

manufacturing soft goods, and so were most likely to appreciate the value of

cotton. Glasgow has all along been the centre of the trade; and nearly, the

whole of the cotton goods manufactured in Scotland are made by or for firms

having their headquarters in that city.

In the year 1787 there were

nineteen mills in Scotland, all driven by water. They were distributed as

follows .—Lanarkshire, fair; Renfrewshire, four; Perthshire, three;

Mid-Lothian, two; other places, six. The second mill in Scotland was built

at Dovecothall, on the banks of the Leven in Renfrewshire. It consisted of

three storeys, measuring fifty-four feet in length, twenty-four feet in

breadth, and eight feet in height. This mill proved so remunerative that it

was soon enlarged, and five similar establishments of considerable size were

erected in the same locality. A cotton mill of what was then considered to

be an immense size was built at Johnstone in 1782, and the locality being

favourable for the trade, others followed, until in 1837 there were eleven

mills in the town. Elsewhere in Renfrewshire numerous spinning mills were

set up about the beginČning of the present century, and a large number of

the inhabitants were engaged in weaving the yarn produced. About thirty

years ago one of the finest cotton mills in the country was built on Shaws

Water, near Greenock; but the only thing that remains remarkable about it is

a water-wheel of 120 horse power. The wheel is said to be the largest in the

world, being seventy feet in diameter. It is composed of iron, and weighs

180 tons.

Renfrewshire had cotton mills

before Lanarkshire; but once the industrial race had fairly begun, the

latter county shot far ahead of the former, and in less than fifty years

from the building of the first factory in the county, Glasgow had become the

centre of a hundred cotton mills. Of the earlier factories in Lanarkshire,

particular mention may be made of that erected at New Lanark in 1785 by Mr

David Dale, one of the pioneers of the Scotch cotton trade. The only

recommendation the site possessed was the prime one, in the eyes of a

manufacturer of those days, of an unlimited supply of water from the Clyde;

otherwise, it was a mere morass. Mr Dale knew the capabilities of the spot,

and set to work accordingly; and simultaneously with the mill he laid out

and built a range of houses for his workpeople. Spinning operations were

begun in 1786; and so well did matters turn out, that a second mill was put

up in 1788. The second mill was destroyed by fire before it was completed,

but was rebuilt in the following year. Subsequently two other ruffle were

erected. Each mill was 160 feet in length by 40 feet in width, and seven

storeys in height. Ranges of stores, offices, mechanics' workshop, foundry,

&c., were also provided. The population of the village, which had been built

in the neighbourhood of the mills, was 2400 in 1820, and of these 1700 were

employed in the works. The surrounding country being unable to supply so

many workpeople, Mr Dale had found it necessary to invite families from a

distance to take up their abode in the village. He also obtained a number of

children from the charitable institutions in Edinburgh. The mills were

placed under the management of Mr Dale's son-in-law, Mr Robert Owen, who

subsequently became notorious on account of his visionary projects for the

regeneration of our social system. Notwithstanding his peculiar notions, Mr

Owen did much to improve the condition of the work- people under his charge.

An educational institution of considerable size was built in the village for

their sole use. It embraced rooms for the various classes of pupils, a

lecture-hall, and a chapel. The course of education included a higher range

of subjects than is usual now-a-days in similar institutions, but at the

same time attention was given to imparting a knowledge of practical matters.

The boys were instructed in gardening and agriculture, and the girls

attended in rotation at the public kitchen to receive lessons in domestic

economy. Judging from an account of the village and its inhabitants written

about forty years ago, the community must have been an exceedingly happy

one. The establishment has changed hands since Mr Owen's day, and is at

present a thriving concern.

Before proceeding to trace

the growth of the cotton trade generally, it is necessary to notice a

circumstance which tended to increase and establish it in the country. The

manufacturers of Glasgow and Paisley had acquired celebrity in making the

finer kinds of linen fabrics before cotton was introduced; and they had not

been long engaged in working the new fibre, when they attempted to imitate

the products of Indian looms. Mr James Monteith, of Glasgow, was the first

to make the experiment; but as the yarn then made in Scotland was not fine

enough for the purpose, he obtained some " bird-nest" Indian yarn, and from

it produced the first web of muslin woven in Scotland. He was so successful

that he wove a second web, from which he had a dress made and embroidered

with gold for presentation to Her Majesty Queen Charlotte. That was about

the time the spinning-mule was invented, and as that machine produced yarn

sufficiently fine for making muslins, many manufacturers turned their

attention to the production of that class of goods. There is evidence of

their early success in a report by the directors of the East India Company,

made in the year 1793, on the subject of the cotton manufacture in this

country. The report states that "every shop offers British muslins for sale

equal in appearance and of more elegant patterns than those of India, for

one-fourth, or, perhaps, more than one-third less in price." Glasgow came to

have an extensive trade in plain and printed muslins, while Paisley acquired

celebrity for fancy fabrics. The joint productions met the public taste, and

the trade being found to be remunerative, was extensively entered into. The

competition with India was made easy by the cheapness of production at home

and the heavy duties which were imposed on goods imported from the East. The

duty in 1787 on Indian muslins and nankeens was L.18 per cent.; in 1802 it

was raised to L.30, 15s. 9d. per cent.; and a gradual increase took place,

until, in 1813, the maximum rate of L44, 6s. 8d. was reached. The duty on

white calicoes was even heavier than on muslins, and in 1813 amounted to

L.85, 2s. 1d. per cent.

The change that took place in

the dress of the people consequent on the introduction of home-made calicoes

and muslins is thus described in Macpherson's Annals of Commerce under the

year 1785: —"The manufacture of calicoes, which was begun in Lanarkshire in

the year 1772, was now pretty generally established in several parts of

England and Scotland. The manufacture of muslins was begun in England in the

year 1781, and was rapidly increased. In the year 1783 there were above a

thousand looms set up in Glasgow for the most beneficial article, in which

the skill and labour of the mechanic raised the raw material to twenty times

the value it was when imported. Bengal, which for some thousands of years

stood unequalled in the fabric of muslins, figured calicoes, and other fine

cotton goods, is rivalled in several parts of Great Britain A handsome

cotton gown was not attainable by women in humble circumstances, and thence

the cottons were mixed with linen yarns to reduce their price. But now

cotton yarn is cheaper than linen yarn, and cotton goods are very much used

in place of cambrics, lawns, and other expensive fabrics of flax; and they

have almost totally superseded the silks. Women of all ranks, from the

highest to the lowest, are clothed in British manufactures of cotton, from

the muslin cap on the crown of the head to cotton stockings under the the

sole of the foot. The ingenuity of the calico-printers has kept pace with

the ingenuity of the weavers and others concerned in the preceding stages of

the manufacture, and produced patterns of printed goods which, for elegance

of drawing, far exceed anything that ever was imported; and for durability

of colour, generally stand the washing so well as to appear fresh and new

every time they are washed, and give an air of neatness and cleanliness to

the wearer beyond the elegance of silk in the first freshness of its

transitory lustre. But even the most elegant prints are excelled by the

superior beauty and virgin purity of the muslins, the growth and manufacture

of the British dominions. With the gentlemen, cotton stuffs for waistcoats

have almost superseded woollen cloths, and silk stuffs, I believe, entirely;

and they have the advantage, like the ladies' gowns, of having a new and

fresh appearance every time they are washed."

The rapid extension of the

cotton trade in Scotland was owing, among other things, to the facility with

which workpeople could be obtained. There was no regulation requiring

special qualifications in those who desired to be employed in the cotton

mills, and, generally, a few lessons sufficed to make boys, girls, or

grown-up persons, quite conversant with the simple duty of attending to the

spinning machines or working at the loom. The wages paid in the factories

were considerably higher than those given to agricultural labourers, and the

result was that many relinquished the plough and became spinners or weavers.

In course of time a redundancy of hands had entered the trade, and the

natural result followed, that wages were reduced. That led to a succession

of ruptures between the masters and workmen, the first of which occurred in

1787, when the masters combined to reduce the prices paid for certain kinds

of work. A scale of prices was drawn up and presented to the workmen, and a

conference was held with the view of arriving at an understanding on the

matter. The result of the conference was not satisfactory to the operatives,

and they formed a combination to resist the action of their employers. They

held meetings in Glasgow, at which resolutions were adopted to expel from

the trade those masters who had become most obnoxious. The expulsion was to

be brought about by the workmen refusing to enter the service of said

masters. It was further resolved that no man should work under a price fixed

by the Union. The contest continued for some time, until a number of the

workmen, unwilling or unable to remain unemployed, took work at the masters'

prices; but they were compelled by their brethren to return the cotton, and

in many instances it was burned. The men continued to assemble in large

bodies, parading the streets; and on the magistrates attempting to apprehend

the ringleaders, they were resisted. The Riot Act was read, the military

called out to the assistance of the civil power, and the workmen not

dispersing, several were killed and others mortally wounded. Prosecutions

followed, which ultimately broke up the combination, and the operatives were

obliged to submit to any terms the masters chose to impose. Subsequently the

workpeople made several attempts to carry their purpose. In 1809 the weavers

of Scotland, in conjunction with those of Lancashire, applied to Parliament

for a bill to limit the number of apprentices and fix a minimum for the

price of labour. Deputies were sent up to support the application, and the

whole circumstances of the trade were investigated by a committee of the

House of Commons; but the conclusion arrived at was that such a measure

would be injudicious, and, consequently, the House declined to interfere. A

similar result followed an application of the same kind made two years

afterwards by the Scotch weavers alone. After being thus thwarted, the

operatives endeavoured to have their wages fixed by two committees, one of

masters and the other of workmen; but though committees were appointed, the

principle of fixing wages was not established. Not discouraged by these

rebuffs, the weavers next had recourse to proceedings under some old Acts of

Parliament, the relevancy of which, though disputed by the masters, was

affirmed by the Court of Session. An action was begun in 1812, which lasted

for ten months, but ultimately failed in consequence of the masters refusing

to bring in counter- evidence, and eventually refusing to recognise the

decision of the judges. A week after the close of the action, 30,000 weavers

struck work in one day, and 10,000 followed soon after. The authorities

interfered, and prosecuted the leaders of the strike. That practically broke

up the Weavers' Union, and the men returned to work after being idle for six

weeks. The dispute between the weavers and their employers was unattended by

serious acts of violence.

The circumstances which led

to combinations among the weavers prompted the cotton-spinners to unite for

the protection of what they conceived to be their interests. Their first

union was formed in 1806; but it did not become conspicuous until 1810,

when, in consequence of its operation, the masters stopped all their mills,

and would not re-admit any of the operatives unless they signed a

declaration that they would not be concerned in any illegal combination, and

would not interfere with their employers as to whom they should employ. For

about six years little was heard of the union; but fresh misunderstandings

arose between the employers and employed in 1816, and between that year and

1824 serious outrages were perpetrated. Several obnoxious employers were

shot at, and their mills were set on fire; while some of the men who

disregarded the dictates of the union were shot, and others were shockingly

injured by having vitriol thrown upon them. In December 1820 an attempt was

made to shoot Mr Orr, manager of the Underwood cotton mill at Paisley, on

the night before his marriage. In August of the same year a workman named

Fisher, who had a large family dependent on him, was shot at when in bed. He

was again shot at next month, and in November he was waylaid while going to

his work, and a quantity of vitriol was thrown on his face and breast, which

burned him dreadfully. As soon as he recovered he resumed work, but the

unionists seemed determined to stop his career, and he was shot at a third

time, fortunately without receiving injury. Several men were wounded by

pistol shots. In 1823 a conspiracy to assassinate one mill-owner and five

spinning-masters was discovered in Glasgow. Threatening letters of the most

diabolical kind were sent out in great numbers.

The oath by which the

combined cotton-spinners bound them-selves was in the following terms:—"I,

A. B., do voluntarily swear, in the awful presence of Almighty God, and

before these witnesses, that I will execute, with zeal and alacrity, as far

as in me lies, every task or injunction which the majority of my brethren

shall impose upon me, in furtherance of our common welfare, as the

chastisement of nobs, the assassination of oppressive and tyrannical

masters, or demolition of the shops that shall be incorrigible; and also

that I will cheerfully contribute to the support of such of my brethren as

shall lose their work in consequence of their exertions against tyranny, or

renounce it in resistance to a reduction of wages. And I do further swear

that I will never divulge the above obligation, unless I shall have been

duly authorised and appointed to administer the same to persons making

application for admission, or to persons constrained to become members of

our fraternity."

A report on trade

combinations was made to Parliament in 1838, in which it was stated that the

Glasgow master cotton-spinners had a combination of a somewhat mysterious

character; they had no written rules, no fixed times or places of meeting,

no regular subscriptions or expenses, except a charge on each master, at so

much for every thousand spindles worked in his factory, for the support of a

secretary. The union of operative cotton-spinners had by that time been

established on a more civilised basis than formerly; and of 1000 spinners in

Glasgow 750 were members of the union. Between 1826 and 1836 a series of

partial strikes occurred, the result of which was to equalise the wages in

the various mills and districts. In the autumn of 1836 the operatives

applied for an advance of sixteen per cent. on their wages, which was

granted by the Glasgow manufacturers, but not by those in the surrounding

districts. The Glasgow unionists were then, as they said, compelled by the

threats of their own masters to strike against a wealthy country

manufacturer who had refused to comply with the demands of his men. The

strike lasted sixteen weeks, and cost the union L.3000, but without

improving the position of the men. In the spring of 1837 trade grew dull,

and the masters who had given an advance of wages proposed to return to the

previous rate. That step the men resolved to resist, and went out on strike;

but at the end of fifteen weeks they gave in, and returned to work at a

lower rate of wages than had been previously offered. During the strike

several outrages were perpetrated. One man was murdered, a woman had vitriol

thrown upon her, and there were two attempts at incendiarism. The direct and

indirect loss occasioned by this strike was estimated to be upwards of

L.160,000. The wages of the spinners were always much higher than those of

the weavers, and notwithstanding the reduction to which they had been

subjected, they were earning after the strike from 20s. to 40s. a-week of

sixty- nine hours. No serious strike has occurred in the trade since 1837,

though frequent disputes have arisen.

Unlike the woollen and linen

trades, the cotton manufacture in Scotland shows little increase in recent

years. The quantity of cot-ton manufactured weekly in Scotland averaged 1652

bales in 1831, 2035 bales in 1835, and 2364 bales in 1840. From that year up

till 1861, the quantity consumed rose and fell according to the state of the

markets. In 1866, when the trade in -England had almost recovered from the

depression caused by the American war, the quantity of raw cotton used in

Scotland was 2500 bales; but in the following year only 1700 bales were

consumed. The trade is being gradually concentrated into fewer hands, the

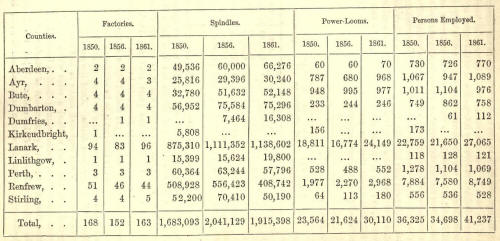

latest returns showing a falling off in the number of factories. In 1838

there were 198 cotton-mills in the country, distributed over the following

counties: —Aberdeen, 4; Ayr, 4; Bute, 2; Dumbarton, 4; Dumfries, 1;

Kirkcudbright, 1; Lanark, 111; Linlithgow, 1; Perth, 7; Renfrew, 60;

Stirling, 3. The total number of steam-engines employed was 193, with an

aggregate of 5612 horse power, and 73 water-wheels, with•an aggregate of

2728 horse power. The number of power- looms was upwards of 15,000, and of

workpeople 35,576. A return made to Parliament in 1862, gives the following

statistics of the trade in the years 1850, 1856, and 1861:—

An attempt was made by the

author to ascertain the present exČtent of the trade by sending schedules to

all the manufacturers; but as several declined to give any information as to

the extent of their factories, though it was explained that aggregate

results only would be published, it is impossible to make a reliable

statement on the subject. From the fact that a number of the schedules

returned blank were accompanied by notes explaining that certain

establishments have recently been converted to other purposes than

manufacturing cotton, while some have been closed, there is reason to

believe that the number of cotton factories in Scotland has undergone a

considerable decrease since 1861, though at the same time it will be seen

from the following figures that the production, as represented by the

quantities of goods and yarn exported, shows an increase:—

Owing to various

circumstances affecting the sources from which the supply of raw material is

obtained and the markets for manufactured goods, the cotton trade of Britain

has been liable to considerable fluctuations; but at no time was it so

seriously disturbed as during the period between the years 1861 and 1866.

The American war almost completely disorganised the trade. The manufacturers

virtually depended on the United States as the one great source of supply,

and to that fact is to be attributed the disastrous crisis which overtook

them on the outbreak of hostilities between the Northern and Southern

States. Amid the turmoil of war the cultivation of cotton was neglected,

stocks in this country rapidly diminished, and the fibre attained a value

which checked consumption—in short, the manufacturing districts became

involved in a cotton famine, attended by an amount of suffering unparalleled

in the industrial history of the nation. When the American war broke out, a

general impression prevailed that it would be of short duration, and only a

slight advance took place in the price of raw cotton.

A few notes on the course of

the market during the eventful -----period referred to will show the effect

of the war on the cotton interests. The quotation for "middling Orleans"

cotton on the 13th September 1861 was 91d. per lb. From that period onward,

however, the advance became decided and rapid, and on the 25th October

middling Orleans was quoted at 12d. per lb. On the 30th November advices

were received of the capture of Messrs Slidell and Mason, from a British

vessel, which event, with the probability of a war ensuing between the

United States and Great Britain, caused a decline in the raw material to the

extent of a ld. to 12d. per lb. From that period the market rapidly

advanced, and continued in a state of intense excitement for several months,

the increase in value being truly prodigious. On the 1st January 1862

middling Orleans was worth 11p. per lb., but on the 15th August was quoted

at 19id. per lb., the advance in that interval being 'lid. per lb. The most

extraordinary phenomenon, however, in the history of the trade, occurred in

the succeeding week, ending 22d August. The stock of American cotton was

computed at 20,080 bales, and of East Indian at 25,150 bales, the total

stock amounting to 81,980 bales. Middling Orleans was quoted at 23• d. per

lb., being an actual advance in the short space of six days of 3id. In the

following week middling Orleans again increased in value to the extent of

3d. per lb., while the total stock of all kinds was reduced to 62,980 bales.

Another advance to the extent of 2d. took place in the following week,

middling Orleans attaining the enormous value of 29d. per lb., or an

increase in three weeks—from the 15th August to 5th September—of 9-sz During

the next eleven weeks the market was on the declining scale, but partially

recovered itself by the end of the year—middling Orleans on the 31st

December being quoted at 25d. The following year, 1863, opened inanimately,

and prices continued without material variation until after the 4th Sep-tember,

when the several facts of extensive orders, both from India and the

Continent, for manufactured. goods, decreasing stocks of cotton in

Liverpool, and the probability of the war continuing, en-gendered an upward

movement in the raw material, which continued with more or less regularity

till the end of the year, middling Orleans on the 31st December being quoted

at 27id. per lb. The imports of East India cotton into Great Britain during

1863 were 1,228,900 bales, being an increase, as compared with 1860, of

666,226 bales.

The first six or seven months

of 1864 were characterised by remarkably high prices, middling Orleans on

the 22d July attaining the maximum value of 31 id. per lb., and "fair

Dhollerah," on the 12th August, 24d. per lb. The stock of American cotton on

the former date was stated to be 3810 bales, but a week previously it was

estimated at only 1721 bales; the total stock, however, was computed to be

212,176 bales. The imports of East India cotton into Great Britain were

1,399,514 bales, or an increase, as compared with 1860, of 836,840 bales. In

1865 the market was very irregular, oscillating according to the tenor of

advices from America. During the first three or four months rumours of peace

negotiations were received from time to time, which, combined with the

ultimate fall of Richmond, exercised a depressing influence on the market,

resulting in the serious decline of 131d. per lb., the quotation in the

first week of January for middling Orleans being 26/d., but on the 21st

April only 13id. At that time, however, news was received of the

assassination of President Lincoln, which caused an immediate reaction, the

market continuing to advance until the 13th October, when middling Orleans

was quoted at 241d. Another period of depression ensued, and middling

Orleans, by the close of the year, declined to 211d. The following year

(1866) was a remarkable one, and will long be remembered in the annals of

the commercial world for the extraordinary combination of adverse and

desponding influences upon every branch of commerce.

Though the manufacturers

suffered severely during the crisis, the sorest burden of distress fell upon

the workpeople. Out of 355,000 persons employed in the Lancashire cotton

factories, only 40,000 were in full work at the close of 1862, and the loss

in wages alone was estimated at L.105,000 a-week; but even then the worst

had not been reached. The state of matters that prevailed in Lancashire

excited the sympathy of the whole country, and brought out one of the most

munificent responses that has ever been made to the cry of distress. The

cotton operatives of Scotland, residing chiefly in places where other kinds

of labour were abundant, did not suffer to the same extent as those in

England, but they did not altogether escape the effects of the calamity.

Local efforts were made to supply their wants, and the manufacturing

communities in the west contributed liberally to support the poor people.

The cotton manufacture has now nearly resumed its normal condition, but the

recollection of those terrible years of famine will linger long in the minds

of all classes engaged in the trade.

Among the most extensive

cotton factories in Scotland are those of Messrs A. & A. Galbraith, situated

at Oakbank and St Rollox, Glasgow. The factories comprise two immense ranges

of somewhat irregular buildings. The original portions were erected many

years ago, and the successive additions may be traced in the different tints

of the masonry. The joint establishments cannot be pointed to as models, so

far as the buildings are concerned; but they are filled with machinery of

the finest and most recent construction, and their internal economy is equal

to that of any other mills in the country. In the spinning department there

are 95,000 mule and throstle spindles, the produce of which is made into

cloth by 1532 power- looms. There are several large steam-engines, the

aggregate indicated force of which is 1600 horse power. 1700 persons, of

whom only 100 are males, are employed; and the quantity of cloth made is

350,000 yards a-week, or 17,000,000 yards a-year. All the cloth is of the

plain kind for printing and dyeing.

The cotton arrives at the

mill in compactly pressed bales, each 4 feet in length by 2 feet in breadth

and height, and weighing on the average about 428 lb. The varieties

generally used are American, Indian, and Egyptian, mixed in certain

proportions. The bales are deposited in large stores, and the first process

is performed in that department. A few bales of each kind are opened at a

time, and their contents thrown into a heap, the quality of the mixture

depending on the proportions of the different varieties of fibre used. The

cotton is then conveyed in wicker-work trucks to a room, where it is

subjected to the action of the "opener," a machine which loosens the large

flocks and separates the grosser impurities. The opener does not complete

the process of purification, and the cotton is passed to the "scutcher," in

which it is made perfectly clean. The inventor of the latter machine was Mr

Snodgrass, of Glasgow, and it was introduced into the trade in 1797. The

third machine through which the cotton is passed is the spreading-machine,

which prepares the fibres for carding. The cotton is spread evenly on a

feed- apron, and after passing through fluted rollers, and being beaten by a

series of revolving-arms, is delivered in a continuous web or fleece which

is wound upon gigantic bobbins. The cotton is now ready for carding, the

object of which process is to disentangle the filaments and lay them

parallel to each other; and the more carefully the operation is performed,

the more perfect will be the yarn produced. The filaments of cotton, when

viewed through a powerful microscope, have the appearance of flattened tubes

of glass, twisted on their axis; while those of flax are perfectly

cylindrical, and jointed like a cane. The normal form of the fibre in both

cases remains unchanged through all the processes of manufacturing, and is

not altered by their reduction to pulp and conversion into paper. The form

of the filaments makes the cotton bear a pretty close resemblance to wool,

which flax never assumes.

The carding-engines consist

of a series of cylinders covered with wire spikes of various degrees of

fineness. The cotton is fed into the carder from the bobbins of the

spreading-machine, and emerges in the form of a ribbon or sliver. As it

comes from the carder the sliver is exceedingly tender and loose, and is

received from the machine in tin cans. If the cotton be examined at this

stage it will be seen that, though the fibres show a general tendency to

parallel arrangement, many of them are doubled and twisted in a way which

would render it impossible to form them into the finer qualities of yarn. On

following the slivers to another set of beautiful machines it will be seen

how the filaments are arranged in perfect order. The process is called

drawing and doubling. The drawing-frame consists of a combination of

rollers, which serve to draw out and elongate the sliver. Their action is

exceedingly simple, and as they form a part of all subsequent machines

through which the cotton is passed until the spinning is completed, it may

be well to explain how they act. Let this represent an end view of the

rollers, which are commonly arranged in three pairs, g g. The rollers are

four inches in circumference, and each pair moves with a different velocity.

We shall suppose that the cotton is fed in between the left hand pair of

rollers, and led on to the others. The speed of the second pair is so much

greater than that of the first, that one inch length of sliver in passing

between them is drawn out to one and three quarter inches, while the third

pair draws it to a length of five inches. This process is repeated until the

requisite degree of parallelism is attained in the fibre, but it will be

evident that were a single sliver put through several times it would become

so attenuated that it would be impossible to manage it. This difficulty is

overcome by what is called "doubling," that is, laying several slivers

together at every repetition of the process. The effect of the drawing and

doubling may be illustrated by taking a tuft of tangled wool and drawing it

asunder several times with the fingers, at each drawing laying the two

separated portions together and seizing them by the extremities. After being

thus drawn five or six times, the wool will be found to have a perfectly

parallel arrangement.

The first spinning process is

done on the bobbin-and-fly frame. The sliver is fed into the machine from

the cans, and, after being drawn out a little, has a slight twist imparted

to it, which makes the fibres cohere, and fits the cotton for bearing

further elongation. As a sudden extension to the wished-for fineness is not

practicable, the cord or "roving" which is formed by the bobbin-and-fly

frame is gradually reduced—first by the fine bobbin-and-fly frame, and

finally by the throstle-frame or the mule. The coarse and fine

bobbin-and-fly frames are essentially similar in principle, but the latter

is more delicately constructed than the former. The bobbins from the fine

frame are placed on the throstle-frame, by which the thread is drawn out to

the requisite fineness and firmly twisted. As the cotton is subjected to one

operation after another, it is elevated from floor to floor, according to

the arrangements of the successive machines; so that by the time the

spinning processes are completed, the cotton has been elevated to the fifth

or sixth floor. Most of the machines are attended by women or girls, whose

work is exceedingly light, and much more healthy than it used to be.

It would be impossible to

conceive machines more perfectly adapted to their purpose than those which

crowd the spacious floors of Messrs Galbraith's factories. Each seems to

work with a will and instinct of its own, and no one can witness their

operations without admiring the ingenuity that devised their thousands of

parts and brought them all into harmonious play. Fingers of iron and wood

work more deftly, and with apparently more delicacy of touch, than fingers

of flesh and blood could ever do; and the finest productions of the Indian

hand-spinners are surpassed by the gossamer-like threads which the

self-acting spinning-mule produces by hundreds at a time.

Respecting the weaving

department there is not much to say, as all the, looms are employed on plain

cotton of various qualities, ranging from fine muslin for summer dresses to

stout calicoes. The manner in which the warp is prepared, the action of the

looms, and the other details of weaving, are so similar to those followed in

the manufacture of linen, already described, that it would be superfluous to

notice them here.

Some of the early travellers

in the East brought home marvellous accounts of the muslins made in India.

Tavernier states that in the city of Calicut, whence comes the designation

of "calico" which is usually applied to muslin, some cloth was made so fine

that it "could scarcely be felt in the hand, and the thread was scarcely

discernible." A missionary at Serampore states that "muslins are made by a

few families so exceedingly fine that four months are required to weave one

piece, which sells at 400 or 500 rupees. When this muslin is laid on the

grass and the dew has fallen upon it, it is no longer discernible." Oriental

hyperbole goes still further, and describes the muslins of Dacca as "webs of

woven wind." It has been proved that, however marvellous these fabrics may

have been when the rude appliances by which they were produced were taken

into account, they were much coarser than the muslins now spun and woven by

steam in Glasgow and elsewhere, and sent in immense quantities to the

countries where the fabric had its origin. Messrs Galbraith do not make any

of the finer qualities of muslins, but many looms in Glasgow are engaged in

producing cloth of exquisite delicacy.

Some of the old hand-loom

weavers to be met with speak of the large wages made in the early years of

the cotton manufacture. At one kind of work a man could earn 7s. 6d. a-day.

The price paid for weaving "causey," or printing-cloth, was 6d. an ell, and

a good hand had been known to turn out twenty yards a-day. That was the

golden age of the hand-loom. In the rural districts farmers apprenticed

their sons to the trade. Weaving was more remunerative than the other

mechanical occupations; consequently, those engaged at it were looked upon

as the aristocracy of the working- class, and a smart weaver lad did not

think himself beneath the honour of seeking and obtaining the hand of the

daughter of the former merchant. Now, hand-loom weavers in the cotton trade

occupy a humble position, and their earnings range, according to ability and

energy, from 12s. to 20s. a-week; but very few reach the latter sum.

According to a return

recently issued by the Board of Trade, the wages of the cotton operatives in

Glasgow are as follow, for the week of sixty hours:—Men—overlookers, 45s.;

warpers, 22s.; drawers and twisters, 20s.; dressers, 33s.; sizers, 35s.

Women—reelers and winders, 9s. to 10s. 6d.; warpers, 14s.; weavers, taking

charge of two or three looms, 11s.; of four looms, 15s. 6d. Girls—taking

charge of one loom, 6s. The persons employed in the cotton factories have

little to distinguish them socially from the great body of the working

population, except, perhaps, that there is a large number of Irishwomen

among them, whose manners are somewhat coarse. |