|

I was born on the 13th of

May, 1842, at the Chateau de Talhouet, not far from the little town of

Quimperle, in the Morbihan, Brittany. It seems I was destined from the

very beginning to pass through life in the atmosphere of the Gulf Stream

and among the Celts, for my dear mother told me the servants in the

chateau all spoke Breton among themselves, and were like west-coast

Highlanders in every way, except that they had the fear of wolves added

to that 01 ghosts and goblins when they had to go out at night and pass

through the Forest de Barbebleue which surrounded the chateau.

As I left France when I

was only just a year old, I cannot tell much about our life in Brittany,

except that the family consisted of my father, Sir Francis Mackenzie,

fifth baronet and twelfth laird of Gairloch; my mother, Mary Hanbury, or

Mackenzie; and my two half-brothers —Kenneth, who became the sixth

baronet and thirteenth laird, and Francis, who was just a year younger,

the boys being respectively ten and nine years of age.

There were in the

household a young French tutor and a Scottish maid, and my father had

brought an Aberdeenshire salmon-fisher with him, with the usual

appliances, such as nets, etc., for the capture of the salmon in the

River Elle. But though there were, and doubtless are, salmon in that

river, I do not think the fishing enterprise proved much of a success.

My mother told me that

immediately after my birth I was taken in charge by the accoucheuse, a

Madame Le Blanc, but during the first night my mother’s sharp ears

thought they heard some small cries from a distant room. So, not

thinking for a moment of herself and the danger to her life, she sprang

out of her bed and made straight for our room, where she found Madame Le

Blanc sound asleep and no one attending to her precious son, whom she

snatched up in her arms and carried back to her bed; no one else was

allowed to have charge of him from that day forward.

Although my father had a

big extent of clicisse to shoot over, there was no game to speak of, and

the bags consisted chiefly of squirrels, which it was the fashion there

to eat, and of which pies were made until the Breton cook struck against

preparing them, declaring they reminded her of skinned babies ! The food

in those days was very poor in Brittany, and the peasants subsisted

chiefly on porridge made of ble noir (buck-wheat). Often, to get decent

rolls and bread, my father had to drive to the town of L’Orient, a good

many miles away.

I was registered in

Brittany by the name of Hector, after my paternal grandfather, Sir

Hector, but afterwards my father, recollecting that the eldest son of my

Uncle John Mackenzie was called Hector, thought two of the same name in

the family might be confusing, so, when we reached England and I was

christened, the name of Osgood was given me, after my maternal

grandfather, Osgood Hanbury, of Holfield Grange, Essex, and also after

my cousin, who was my godfather. The eldest sons of these Hanburys were

always called Osgood from 1730, when John Hanbury, son of Charles and

Grace Hanbury, of Pontymoil and other estates in Monmouthshire, married

Anne, daughter and heiress of Henry Osgood, of Holfield Grange, who held

3,392 acres of land in the parish of Coggeshall. I have always rather

regretted that my original name of Hector was not adhered to, as our

family has, since about 1400, been known as Clan Eachainn Ghearloch

(children of Hector of Gairloch), and Eachainn MacCoinnich would have

been so much more appropriate when writing my signature in Gaelic.

My readers may wonder at

my writing anything about a place which I could not possibly have viewed

with intelligent eyes when I left it, but I renewed acquaintance with it

many years later. When I was about thirty my mother and I made a tour

through Normandy and Brittany, one of the chief aims of which was to

visit my birthplace. I remember we arrived at Quimperle on a Saturday

evening, and I soon found out that the following day there was to be a

religious festival, what they called in Brittany a <e Pardon,” finishing

up in the evening with unlimited music and dancing in the Grande Place

of the town. Thousands of peasants had come in from the surrounding

country, many of the older men in the native costume—their nether

garments being like the most voluminous of knickerbockers—and the women

with their wonderful coiffes. Dancing was in full swing to the music of

the biniou, the Breton bagpipes, and the music and dancing were

certainly first-cousins to our Highland bagpipe music and reels.

After a struggle I

managed to make my way through the crowd to the side of the old piper,

and during the short intervals between the dances 1 carried on a brisk

conversation with ljim in French on the subject of bagpipes. I informed

him that we had nearly the same kind of pipes in the North of Scotland,

and that we also spoke an ancient language related to the Breton. He

suddenly brightened up and became quite excited. Talking of Scosse, he

said, reminded him of days long gone by, when he was a lad, and there

was a Monsieur Ecossais living in the Chateau de Talhouet not far away,

a big gentleman with reddish hair and whiskers. Whilst monsieur was

there, a baby son was born and a dance was given, for which he was hired

as musician. My mother could well remember that dance being given and

the hiring of the piper, and here was the very man who had played all

night in honour of my birth!

Another curious

coincidence I must mention here in connection with the Chateau de

Talhouet, which was in olden times the seat of a great Breton nobleman,

the Marquis de Talhouet. About two years ago, during the late war, when

Lochewe was a naval base, a French warship came in, and as none of the

naval officers stationed at Aultbea happened to be very fluent in French

and the French officers were said not to be very good at English, I was

asked to entertain half a dozen of them at luncheon. It turned out that

the mother of one of these officers was then actually owner of the

Chateau de Talhouet and was residing in it!

On the Monday after the

gay scene in the Grande Place of Quimperle, my mother and I drove out to

the chateau that she might show me the very room in which I was born;

but though the then owner, whose name was, I think, the Comte de

Richemond, was most kind and hospitable, he had so much improved and

altered the chateau that my mother could hardly make sure of the actual

room where I first saw the light. One thing, however, she did recognise,

which she had often described to me, and that was a magnificent specimen

of the tulip-tree which grew on the lawn. How well do I remember the

dinner in the inn at Quimperle, where everything was very old-fashioned,

and where the host sat at the head and the hostess at the foot of the

table. There was great excitement over something unusual which had

occurred that morning—namely, the catching by the Gendarmes of a young

priest poaching the river, with a fresh-run salmon in his possession.

The ladies all took the side of the priest, whilst most of the men

supported the authorities. The salmon was to be sold by public auction,

and the ladies all swore solemnly that none of them would bid at the

sale, as it was monstrous that their Father Confessor should be deprived

of the fish which he had captured so cleverly.

When my father and his

family left Brittany, we stayed a short time in Jersey, but all I can

remember to have heard of the visit to that charming island was that I

there first showed a love of music, which has continued all through my

life. I was told that when a brass band played I almost jumped out of my

mother's arms. A friend of my father, a Colonel Lecouteur, gave a

dinner, and the dessert consisted of pears only, there being thirty

dishes, each containing a different variety. So it seems that their

culture was pretty well advanced even as far back as 1842.

And now my memory of the

events that happened for a couple of years is more or less vague, and I

can depend only on what I was told by others. Soon after our arrival in

England my father became very ill, and, according to the stupid practice

of doctors in those days, he was bled in the arm, erysipelas set in, and

he died in the course of a few days. His remains were taken north by

sea, from London to Invergordon, by my mother and her brother and

sister, to be buried in the family burying-place in the old ruined

Priory of Beauly. I was just a year old when this calamity happened, and

consequently can remember nothing of the voyage north or anything else

for some time after. But subsequent voyages of a like kind when I was

four or five years old made impressions on me which have never been

forgotten. How well I remember, as though it were only yesterday, a

horrible voyage from Invergordon to London in a kind of paddle-boat,

which lasted nine whole days! We called at every small port along the

Banffshire and Aberdeenshire coasts for dead meat for the London market.

Stacks of it were piled up on the deck, and consisted chiefly of dead

pigs. By way of amusing me, our butler, Sim Eachainn (Simon Hector), cut

off many of the black and white tails and presented them to me as toys!

Then we were stuck for some days in a dense fog at the mouth of the

Thames. It was a never-to-be-forgotten voyage, though it was not as long

as a voyage my uncle took as a young man, when he was seventeen days in

a smack sailing between London and Inverness, and even then he never

reached it, but had to disembark at Findhorn.

On our return journey

north my mother wished to go by land, but it was, if possible, even less

successful. I cannot remember how we got to Perth, but from there we

travelled by the Highland stage-coach. It was mid-winter, and we managed

to get as far as Blair Atholl, when a violent snowstorm started, and a

few miles beyond the village, the coach was suddenly brought to a

standstill by trees being blown across the road both in front and behind

us. A runner was despatched for a squad of men with saws and axes, but

the blizzard was so severe that by the time help came the coach could

not be moved on account of the depth of the snow, and we got back to

Blair Inn by the help of a very highwheeled dog-cart. How well I

remember being lifted by our faithful Simon and carried in his arms to

the trap ! After being kept prisoners at Blair for several days, we

managed to get back to Perth, whence we got to Aberdeen by the newly

opened railway, and from there to Inverness by steamboat. Thus the land

journey was not altogether a success, and we had to fall back upon the

sea after all to get us north.

My father in his will had

appointed my mother and Thomas Mackenzie, the laird of Ord, as trustees

for the Gairloch property during my elder half-brother's minority, and

my father's brother, John Mackenzie, M.D., of Eileanach, was to be

factor on the estate. For the first six months or year after my father's

death my mother resided at Conon House, near the county town of Dingwall,

which was the east coast residence of the Gairloch family. The Conon

property was a comparatively small one, with a small population, whereas

Gairloch consisted of some 170,000 acres and a large crofter population

of several thousand souls; so my mother felt it her duty to remove there

and make it her permanent home. It was not very easy getting from Conon

to Gairloch in those days, for, though a road had been made from

Dingwall to Kenlochewe, or rather two miles farther on to Rudha n'

Fhamhair (the Giant's Point), at the upper end of Loch Maree, there was

still no road for some twelve miles along the loch-side, and often it

was stormy and the loch difficult to navigate in small rowing-boats.

But Gairloch was far more

difficult of access in the days of my grandfather and my uncles. I shall

now quote from what my uncle says regarding the annual migrations to and

from Gairloch. In those days the larger tenants had, if required, to

provide several days" labour by men and horses for the journey. My uncle

writes: “My eyes and ears quite deceived me if those called out on these

migration duties did not consider it real good fun, considering the

amount of food and drink which was always at their command." A troop of

men and some thirty ponies came from Gairloch, and would arrive, say, on

a Tuesday night, and all Wednesday a big lot of ponies, hobbled and

crook-saddled, was strewed over our lawns at Conon, with a number of men

and women helpers hard at work packing. Everything had to go west—flour,

groceries, linen, plate, boys and babies, and I have heard that my

father was carried to Gairloch on pony-back in a kind of cradle when he

was only a few weeks old. The plan usually followed was to start the mob

of men and ponies about four o'clock on the Thursday afternoon for the

little inn at Scatwell at the foot of Strathconon; and as there was a

road of a kind thus far and no farther, the old yellow family coach

carried “the quality ” (i.e., the gentry) there before dark.

There were several great

difficulties in those days. One was the crossing of the various fords

over the rivers, and the next was keeping dry all the precious things

contained on the pack-saddles, including the babies. The great

waterproofer, Mackintosh, was unborn and rubber was still unknown, so

they just had to do their best with bits of sheep-skins and deer-skins,

which were not very effective in a south-westerly gale, with rain such

as one is apt to catch along Druima Dubh Achadh na Sine, the Black Ridge

of Storm Field, as Achnasheen is very properly called in Gaelic.

Next morning the start

was made at six o’clock right up Strathconon and across the high

beallach (pass) into Strath Bran, and on and on till Ivenlochewe was

reached, which ended the second day at about seven o’clock at night. I

have been told that my grandfather was always met at the top of

Glendochart, where one first comes in sight of the loch, by the whole

male population of Kenlochewe, every man with his flat blue bonnet under

his arm, and they followed the laird’s cavalcade bareheaded till it

crossed the river to the inn. The old inn in those days was on what we

should now call the wrong side of the river, and the crossing was often

a great difficulty. Sometimes the children were carried over by men on

stilts, which was thought great fun by them. The welcome at the inn my

uncle described as “ grand.” The poor landlady was twice widowed, both

her husbands having been drowned in trying to get people across this

wild river on horseback when it was in flood. My uncle fancied that what

made the widow suffer most was perhaps the fact that neither husband was

ever found, both being at the bottom of Loch Maree, and that she had not

had the great relief and even “pleasure” of burying each of them with

unlimited whisky, according to custom ! I can well remember one of her

sons. He was by far the most skilful carpenter in our part of the

country, and was always known as Eachainn na Banos-dair (Hector of the

Hostess). My uncle says that if ever the Gairloch family had a devotee

it was Banosdair Ceann-Loch-Iubh (the hostess of Kenlochewe), and he

believed she would cheerfully have gone to. the gallows if she were

quite sure that would please the laird.

The following morning the

party had only two miles to go to Rudha n’Fhamhair (Giant’s Point),

where the family and all the precious goods and chattels were stowed

away in a small fleet of boats and rowed or sailed some ten or twelve

miles down the loch to Slata-dale, where the then comparatively new

narrow bit of road, more or less adapted to wheels, ran from this bay of

Loch Maree to the old mansion of Tigh Dige nam gorm Leac, which, as my

uncle says, “ was looked upon by us Gairlochs as the most perfect spot

on God's earth." Eor the sake of the boys a halt was always made at one

of the twenty-five islands in the loch for a good hunt for gulls' eggs,

but in truth it did not require much hunting, for my uncle says he and

his brothers could hardly keep from treading on the eggs, the nests were

so plentiful among the heather and juniper. I can remember them equally

numerous till I was about fifty years old, when the lesser black-backed

gulls very gradually began to go back and back in numbers, until, alas !

they are now all but extinct.

I shall give my readers

my uncle's description of the arrival of the cavalcade on the Saturday

evening at the old home, the most perfect wild Highland glen any lover

of country scenery could wish to see. No sheep, he says, had ever set

hoof in it; only cattle were allowed to bite a blade of grass there; and

the consequence was that the braes and wooded hillocks were a perfect

jungle of primroses and bluebells and honeysuckle and all sorts of

orchids, including Habenarias and the now quite extinct Epipactis, which

then whitened the ground, and which my uncle says he used to send as

rare specimens to southern museums. May I remark here that in the course

of my long life in the parish of Gairloch I have only twice had the

pleasure of seeing the Epipactis ensifolia—once near the Bank of

Scotland at Gairloch about thirty years ago, and one other specimen on

the edge of the stream of the Ewe fifty yards above the boathouse at

Inveran. I found plenty of them in the woods of the Pyrenees.

My uncle continues:

“Having arrived at long last at the end of our three days’ journey, we

boys wanted but little rocking ere we were asleep in our hammocks. Next

morning (Sunday) before six, all who were new to the place called out c

Goodness gracious, what’s the matter, and what’s all this awful noise

about V for sixty cows and sixty calves were all bellowing their hardest

after having been separated for the twelve hours of the night. They were

within eighty yards of the chateau, and, assisted by some twenty herds

and milkers screaming and howling, they made uproar enough to alarm any

stranger just waking from -sleep, who expected a quiet, solemn

west-coast Sabbath morning. This was a twice a day arrangement.

Eventually the grass in the Baile Mor Glen was eaten pretty bare, and

then the whole lot of them went off to the shieling of Airidh na Cloiche

(Shieling of the Stone) for the summer.

There was a dyke about

one hundred yards long between the entrance-gates at the bottom of the

lawn and the Allt Glas burn which kept the cows and calves separate, to

the great indignation of both parties, who bellowed out their minds

pretty plainly. Domhnall Donn (Brown Donald), the head cowman, brought

his wailing friends the cows to the west side of the wall, and his

subordinates brought the calves from their woody bedrooms where they had

passed the night on the east side. And then began an uproar ofc Are you

there, my darling V ‘Oh yes, mother dear, wild for my breakfast/ Then

the troupe of milkmaids entered among the mob of bawling cows by one of

the small calf-gates in the wall. They carried their pails and

three-legged little stools and buarachs (hobbles) of strong hair rope,

with a loop at one end and a large button on the other. The button was

always made of rowan-tree wood, so that milk-loving fairies might never

dare to keep from the pail the milk of a cow whose hindlegs were buarach

(bound)!

“All was soon ready to

begin. A young helper stood at each gate with a rowan switch to flick

back the overanxious calves till old Domhnall sang out, looking at a cow

a dairymaid was ready to milk, named, perhaps, Busdubh (Black Muzzle), ‘

Let in Busdubh's calf/ who was quite ready at the wicket. Though to our

eyes the sixty black calves were all alike, the helpers switched away

all but young Busdubh, who sprang through the wicket; after a moment's

dashing at the wrong cow by mistake, and being quickly horned away,

there was Busdubh Junior opposite to its mother's milker sucking away

like mad for its supply, while the milkmaid milked like mad also, to get

her share of it. The calf, I suspect, often got the lesser half, for the

dairy people liked to boast of their heaps of butter and cheese, leaving

the credit or discredit of the yearly drove of young market cattle to

Domhnall and his subordinates. I have seen young Busdubh getting slaps

in the face from its enemy the milker, who thought she was getting less

than her share of the spoil; and then calfy was dragged to the wicket

and thrust out, and perhaps Smeorach's (Thrush's) calf halloaed for

next. This uproar lasted from six till nine, when justice having been

dispensed to all concerned, Donald and company drove the cows away to

their pastures, and the junior helpers removed the very discontented

calves to their quarters till near 6 p.m., when the same operation was

repeated.

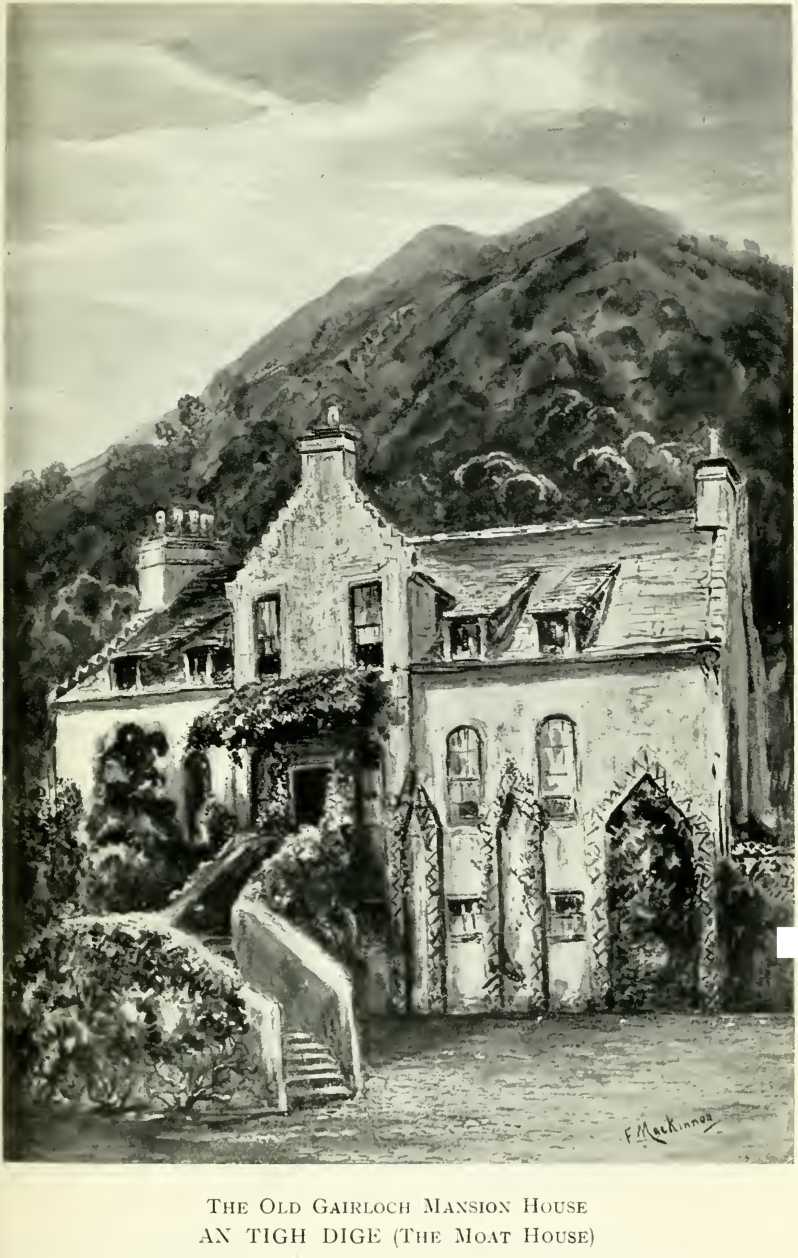

“And then the procession

of milkmaids stepped away to the dairy, which was a projecting wing of

the Tigh Dige and is now part of the garden, carrying the milk in small

casks open at the top with a pole through the rope-handle of the cask,

the two milkers having the pole ends on their shoulders. And now as to

the dairy. No finery of china or glass or even coarse earthenware was

ever seen in those days; instead of these, there were very many flat,

shallow, wooden dishes and a multitude of churns and casks and kegs,

needing great cleansing, otherwise the milk would have gone bad. And big

boilers being also unknown, how was the disinfecting done, and how was

hot water produced ? Few modern folk would ever guess. Well, the empty

wooden dishes of every shape and size were placed on the stone floor,

and after being first rinsed out with cold water and scrubbed with

little heather brushes, they were filled up again, and red hot dornagan

(stones as large as a man's fist), chosen from the seashore and

thoroughly polished by the waves of centuries, which had been placed by

the hundred in a huge glowing furnace of peat, were gripped by long and

strong pairs of tongs and dropped into the vessels. Three or four

red-hot stones would make the cold water boil instantly right over, and

the work was then accomplished. But oh, the time it took, and the amount

of good Gaelic that had to be expended,

and more or less wasted,

before the great dairy could be finally locked till evening came round

again!”

In my grandfather’s day

no colour was considered right for Highland cattle but black. The great

thing then was to have a fold of black cows. No one would' look at the

reds and yellows and cream and duns, which are all the rage nowadays.

Though the blacks have since become unpopular, I have been told by the

very best old judges of Highland cattle that there is nothing to beat

the blacks for hardiness, and that the new strains of fancy-coloured

cattle are much softer, and have not the same constitutions.

The Tigh Dige (pronounced

Ty digue), or Moat House, was so called because the original house

belonging to us, which was down in the hollow below the present mansion,

was surrounded by a moat and a drawbridge. The first Sir Alexander, my

grandfather’s grandfather, the Tighearna Crubach (the Lame Laird),

finding it inconvenient, started building the present house about 1738,

and as it was the very first instance in all the country round of a

slated house, the old name Tigh Dige was continued, with the addition

given to it of nam gorm Leac (of the Blue Slabs). I believe iron nails

were used. But I remember the late Dowager Lady Middleton telling me

that when they bought Applecross and had to take off a part of the old

roof of the house they found that the original slates had been fixed to

the sarking with pegs of heather root. She had been told that a man had

been employed a whole summer making heather pegs with his knife, right

up in Corry Attadale, in the heart of the Applecross deer forest. This

shows the difficulty of getting nails in those days!

It was long after this

that some English tourists, finding the lovely Baile Mor Glen peculiarly

rich in wild-flowers, proposed to my ancestor that it should be named

Flowerdale! I am thankful to say I have never once in the course of my

whole long life heard the house called otherwise in Gaelic than the Tigh

Dige and the place am Baile Mor (the Great Town or Home). The cause of

the flowers being so plentiful in the good old times was that neither my

grandfather nor his forbears would ever hear of a sheep coming near the

place, except on a rope to the slaughter-house. The stock consisted of

sixty Highland milk cows and their sixty calves, besides all their

followers of different ages. These were continually shifted from place

to place, and this gave the plants and bulbs a chance of growing. I

never saw the black cattle on the Baile Mor home farm, but my mother,

who was married some years before I was born, saw the whole system in

full swing, and has often told me all about it. |