“Should not his care

Improve his growing stock, their kinds might fail;

Man ?night once more on roots and acorns feed."

—SOMERVILE.IT

was the jubilee of the Talladale Farmers’ Club, and the occasion was

being celebrated in a characteristic fashion. There had been a 4

P.M. heavy dinner of broth, joints, and plum pudding, to which I and

a friend had been invited. It was a somewhat solemn and silent

function, and ominously temperate. Then the tablecloths were swept

away, and rummers and glasses, with basins of lump sugar, were

placed on the table, and bottles of whisky in profusion, apparently

in the ratio of one bottle to three men, were set down, while large

black kettles of boiling water were handed round by waiting-maids

before being placed by the fire.

The loyal toasts were given and received with great heartiness;

after which pipes were stuffed and kindled, and a loud hammering and

applauding accompanied the rising of the Chairman to propose the

toast of the evening—“Prosperity to the Farmers' Club.” He spoke

with a voice clear as a cornet, and began by addressing his

expectant hearers as “Brother farmers all, high and low, that is,

hill men and low country men; few if any of you have seen the span

of years, or experienced the variety of seasons, or weathered the

severity of storms, that I have during the period of my occupancy of

the farm of Buccleuch; and few can make the boast which I can, viz.

that for two long leases, or rather for thirty-nine years, I have

never missed paying my rent punctually and in person.

“I can only touch on some few of the changed conditions during that

period. First of all, the system and practice of husbandry is kept

up to a high standard, and the most is got out of the land that it

will yield; but this only with the expenditure of much capital, with

the exercise of much skill, and through the results of oft-repeated

experience. But there has been a marked decrease in value of produce

of all kinds, the returns from all classes of farms showing a

decided falling off from the average of preceding years. This

decrease has been in greater contrast in the case of secondary and

inferior produce (good articles, whether grain or live stock, never

feel the fall so much as inferior articles), and this would seem to

point to the importance of keeping our land in good heart so as to

grow the best possible crops, and to breed and feed only the best

possible animals.

“Accompanying the fall in prices, we have had to pay more for our

working expenses, and for nothing so much as labour. The

introduction of machines has done away with some of the extra labour

formerly employed for harvesting and at odd times, and that has to

some extent caused people to move into the towns; but one of the

real and main causes of rural depopulation lies in the restless

spirit of the age, and the desire of the people themselves. I would

counsel the ploughman to pause before he gives up a house rent free,

which is kept up for him, his cow, his pig, his hens, and his money

wage, paid regularly rain or shine, and moves into the town, where,

though wages for himself and his family may be better, the expense

of living is out of all proportion higher.

"A new feature of rural life is the invasion of even the remotest

districts by so-called grocers' vans. These are very detrimental to

farming life, bringing as they do tinned meats, patent medicines,

and cheap literature; none of which are so wholesome as the oatmeal

and milk or the old books and papers. One class does not change a

great deal, and that is the shepherds, more notably the hill

shepherds. A good man who can mow, cast peats, and cut sheep drains

is always sought for.

“If, then, we breed good stock we shall yet for a while hold our

own; and if we are left freedom of contract, and if the transfer of

land is made easy and cheap, even under the many adverse conditions

we suffer from, we shall be able to keep up the good repute of

Border farming, and maintain the high standard of Border live

stock."

He gave some most interesting reminiscences of his youth, and of the

habits and customs of the hill farmers, and told some very droll

stories of sayings and doings at the annual kirns, and wound up by

again charging us to be pointed in stock-breeding, and punctual in

payment of rent.

Toast and song followed in quick succession. Pat Murray, a

jovial-looking young fellow, sang a pathetic song in a way that

nearly made us all weep; and his pal, John Fraser, a sad-looking

soul, sang one of the most comic of comic songs with the drollest

pantomimic gestures.

Then the Croupier rose to propose a toast, and my neighbour

whispered that this person had three or four long words which he

dragged into every speech he made, and offered to lay me five to

four that he would use them all to-night. “Ventilate” and

“obfuscate” had at one time been prime favourites, but had long been

discarded as being no longer impressive; and the others, which I was

soon to hear, were of a similar nature. He was a preternaturally

solemn-looking old gentleman, wise as he looked, and very outspoken;

and it was with some trepidation that I gathered he was proposing

the toast of Foxhunting, and addressing his remarks to me, as if

challenging contradiction. He was sure the present Master was not

one to desire to connect, still less amalgamate, the sport of

fox-hunting with that of horse-racing and its concomitant gambling,

for the two were diametrically dissimilar and ran counter the one to

the other; the first being a wholesome and natural recreation, and

the last being an unhealthy and artificial method of producing

excitement. He wished to promulgate his opinion far and wide that he

loved the one and abominated the other—in fact, he looked upon the

gambling element of the latter as the “incarceration” of the devil.

(Loud applause.) He wound up by hoping his hearers would homologate

his sentiments and drink to “Fox-hunting.” He apparently added

something more, but his closing remarks were drowned in a wave of

applause that swept round the table, gathering increased force as it

reached my neighbourhood, and carrying several glasses off the

table.

Two excited lads sprang to their feet, then upon their chairs, and

lastly in emulation upon the table, to second the Croupier’s toast.

The more likely-looking competitor was hauled down, along with

several bottles and decanters; and the other, a rather shy,

awkward-looking youth, was held in position and charged to “spit it

out.” A half tumbler of raw whisky was handed up to him, and this he

swallowed at a gulp without winking, and then declared the one thing

that induced him to offer for his farm, lying in the forsaken and

remote locality it did, was the fact that a pack of fox-hounds

hunted within reach. He worked hard all summer, staying at home,

while he sent his wife to Spittal-on-Tweed. Here his intimates

jeered derisively, for the lady in question was known to do exactly

as she pleased. He took his holidays in winter, on the Saturdays

with the hounds; and this relieved the monotony, enlivened the

existence, and brightened the dark days between Martinmas and

Whitsunday. He met his friends, compared notes with them as to the

condition of their stock, the stage of their farm work, and

sometimes galloped over their young grass and knocked down their

fences in return for similar compliments paid to him. He was always

pleased to see hounds and a good field, for whom he always had a fox

in his whin cover, and a cut of mutton ham and some mountain dew to

wash it down. He was applauded to the roof.

My reply was much interrupted by “Hear, hears” —the audience was in

a mood to cheer, and cheer they did; so that if there was a fox

within three miles of the Cross Keys that night, he must have

shivered in his kennel.

The company then broke into knots of three and four, and

conversation was very animated, being carried on by some in

confidential whispers, and by others in loud declamation that might

have been mistaken for quarrelling, but was only meant to emphasise

the various propositions laid down.

The fun was at its height when I noted a hard-featured hill farmer,

whom I only knew by sight, trying to fix me with his eye. When he

had caught mine, he pushed a gigantic tortoise-shell snuff-mull into

my hand. After accepting this form of hospitality, and returning the

mull, I found him alongside of me, and was puzzled by his repeating

again and again—“Will ye cummanshemenslaige, cummanshemenslaige?”

A mutual friend translated the mystic utterance, which turned out to

be “Come and see my ensilage" an invitation to inspect the contents

of a silo which he had recently established to his own satisfaction

and his neighbours’ wonder and contempt. He was very old-fashioned

and conservative in most respects; but occasionally made an outbreak

into modern experiments, and this was his latest departure.

Promising to “cummanshemenslaige” on Saturday, and being adjured to

be in good time in a manner so earnest as to draw up a picture of

the possibility of the silo going off in spontaneous combustion

before then, and being reminded that “Saturday was to-morrow, and

that to-morrow was Saturday" we made our escape about 1 A.M.

Friday was spent in kennels, which were visited by several belated

sportsmen, one or two of whom let out the fact that the jubilee

celebrations were still in progress.

The puddles were covered with a thin coating of ice as we left the

courtyard on Saturday morning, and they crackled sharply under

“Merrylass” feet as she stepped briskly away; and where the sun had

touched the road, the mud flew in thick flakes from the wheels of

the dog-cart; and all human and horse foot-marks were clear and

distinct on the slight peppering of snow that had dusted the country

overnight. My companion was a young Australian, just home from the

back blocks of Queensland, and much interested in all the signs and

symptoms of rural life, and an experienced tracker.

After leaving the village we came suddenly upon the youth, John

Fraser, one of the most hilarious of the revellers ot two nights

ago. He was leading a cob without a strap of harness on him by the

simple expedient of a muffler round its neck, and was carrying a

driving whip. He explained that the cob’s forelock had come away in

his hand, and he exhibited the tuft in confirmation, but offered no

explanation why he happened to be leading it by so frail a medium.

He evaded answering all questions as to how he came to be reduced to

this pass, merely stating that he was returning to the town. He was

grateful to the Australian for showing him a way of leading an

unwilling horse by a noose of whip-cord passed round the lip and

lower jaw under the tongue, and known to bushmen as the “humane

twitch.” He inquired, rather anxiously, what road we were taking,

and refused all offers of assistance.

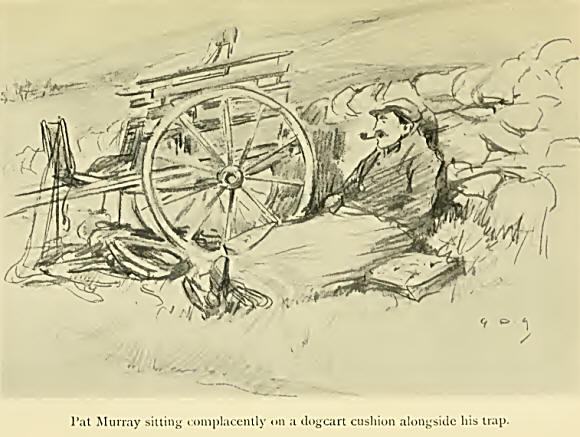

About a mile further out, on rounding a corner, we saw John’s boon

companion, Pat Murray, sitting complacently on a dog-cart cushion,

alongside his trap, with the harness piled on the ground, and a

horse-rug wrapped round his knees, smoking his pipe. Pat was as

communicative as his pal had been reticent, and cried out, in answer

to our query what was wrong, that he and John had cast out badly

over the questionable soundness of a cob that John had almost sold

to him ; that they had agreed that a continued journey in each

other’s company would be deteriorating to both; that this being

decided, John had taken out his cob and proceeded to lead him off,

when Pat reminded him that the harness was his, and he would rather

it was left with the cart. John had demurred to this, but Pat had

insisted, so there was nothing for it but to comply, and march off

with as much dignity as could be put into the action of dragging a

snorting unwilling beast along by the nose and the forelock. John

had returned to claim his whip, giving an opening for a

reconciliation, but Pat had been obdurate, and had laughed loud when

“the Mugger,” drawing back from the whip, had left his forelock in

John's hand and trotted off, nose and tail in the air; nor did he

assist in the capture of the animal, but shouted out, “We’ll see

who’ll be home first.” He, too, declined all offers of help, saying

he was all right and would soon be picked up by a passing chance.

So we continued our

journey, and the Australian exclaimed: “I have been studying the

tracks on the road, and there has been some loose driving here, and

not so long ago, for they are quite fresh;” and as we proceeded he

said, “Will you go slowly here, and let me examine them?”

Our road now branched off to the left from the main valley, and lay

across an unfenced moor, and the powdering of snow showed every mark

conspicuously, which my friend read like a book.

“Look here,” he said, “this chap has been galloping hard and swaying

from one side of the road to the other,” as he pointed out tracks

now running close to the shallow ditch close to the bank, and now

perilously near the edge, where a row of stones was all the parapet

to guard a wheel from going over the ten foot drop into a

watercourse on the other side. “It's a broad flat-tyred trap,

probably a grocer’s van, and there is another lighter trap, with

narrow round tyres. And, by Jove, the fellow has been racing—at any

rate the rear trap has been flogging and trying to pass.”

Sure enough, a whip broken through the whalebone, and marked as if

it had been run over, lay across the road, and Moncrieff's surmise

appeared to be correct, for the tracks now showed a less rapid pace

and straighter going. At the foot of a hill the sharp eyes of the

tracker picked up a cap by the side of the road, and shortly after

this the two traps seemed to have pulled up, for the road was

paddled with footmarks, and strewn with countless spent matches.

At the end of the road leading through the ford to the snug

farmhouse of Nether, or Under, Fawhope, stood Jim Peebles waiting

for us. We had barely pulled up when, anticipating the question, he

at once said: “We only got home from the dinner this morning just

before daylight, and what a job I had with my cousin, William

Peebles. We left the Cross Keys at closing time last night, but we

put in at the Doctor’s for an hour or two, leaving there about three

or four o’clock. William maintained that his pony could out-trot my

mare, giving me half a mile start, and I set off before him, and

about the crossroads he came galloping and barging behind me like at

a bumping boat race, and I had to gallop to save my dog-cart from

being crashed into. He was for coming in here, and his pony would

hardly pass the road end, and set my mare on jibbing at the ford,

and when I hit her she flung up to the dash-board, a thing I never

knew her do before. But come away, Upper Fawhope is only

three-quarters of a mile on, and we’ll just be in time for lunch.”

He strode after us with the long swinging stride of a hill shepherd,

and kept up to “Merrylass” quick walk without effort. We found

William Peebles sitting on a stone at the turn off of his road,

watching a young lad who was applying a liberal wash of whitening to

a row of large stones marking the turn.

“Good morning, gentlemen,” said he. “These stones are not easy seen

on a black night. The last time Jim Peebles was in here he drove

over most of them; I see his tracks.” And he added half

hesitatingly, “They might be useful to you going out to-night.”

“Here is your whip, William,” said his cousin, coming up. “Mr.

Moncrieff found it below the cross roads.”

“I must have dropped it when I got out to look for my cap.”

We remembered there had been an interval of about a mile between the

whip and the cap, but we said nothing.

“1 couldn’t find the second step of my trap,” he continued, “and

slipped and cut my head a bit.”

"Mr. Moncrieff here says there is a very wobbly driver in the

valley, William—a man who drives a flat-tyred broad wheel.”

“Ah, ah, Jim, that’s you; ye mind ye had your wheels new ringed by

Robbie Tamson just a fortnight since. Mine has a narrow round tyre,

and makes a track like a velocipede. But open the gig-house and

we’ll see it.”

The gig-house doors were opened, and there stood Jim Peebles’ cart,

and in the stable an unconcerned-looking boy was wiping down Jim

Peebles’ mare. William gasped and looked as if he might have

explained away the cart, but the two together, cart and mare, were

too weighty evidence against him; so producing his snuff-box,

removing his cap, and displaying a bandaged head, he said, "Well,

that accounts for the bezzom reisting on the hill and cutting across

the grass at the corner. But,” he added, with confidence, “I’ll take

my davy that I started in my own trap. We must have changed them

when I was looking for my whip, for I mind kindling a match there

and sheltering it from the wind with my cap.”

We lunched lavishly; and two more hill farmers having stepped in, we

listened attentively to the characteristics of hoggs and gimmers and

t’winters and dinmonts till it was discovered to be too dark to

inspect the silo; but Jim, the lad, was instructed to put a cut in

the dog-cart for us to carry home. This we did as far as the first

ravine, into which Moncrieff tossed it with his ungloved hands,

declaring he would never be able to taste Gorgonzola cheese for the

rest of his life. |