IT is a curious fact that the

means of producing artificial excitation, or a pleasing flow of animal

spirits, is one of the earliest objects of human solicitude. No sooner

have herds been domesticated and the land brought into cultivation, than

the invention of man discovers the art of preparing an exhilarating

beverage. To the people of the east and the southern countries of Europe,

the vine afforded a delicious treat, the want of which the Gauls and

Britons supplied from grain, and the liquor prepared from it they named

Curmi, a word retained in close resemblance by the Welsh, whose term for

beer is Cwrw; the Gaël have lost this word, but they retain Cuirm, a

feast, and call ale Loinn, the Llyn, or liquor of the former.

It was reserved for the northern

descendants of the Celtic race to improve on the process of fermentation,

and by distilling the Brathleis, or wort, they became the noted preparers

of Uisge beatha. This term is literally "the water of life," corresponding

to Aqua vitae, Eau de vie, &c., and it is from the first portion of the

word that ‘Whiskey’ is derived. It is otherwise called Poit du’, or the

black pot, in the slang vocabulary of the smuggler, the Irish Poteen, or

the little pot, being of similar import.

The superiority of small still

spirits to that which is usually produced in large licensed distilleries,

is supposed to arise from the more equable coolness of the pipe, a regular

supply of spring water being introduced for the condensation of the steam

and the Braich, or malt, is also believed to be of a better quality, being

made in small quantities, and very carefully attended to. As the

preparation of malt for private distillation is illegal, it must be

managed with great secrecy, and the writer has seen the process carried on

in the Eird houses, often found on the muirs, which, being subterraneous,

were very suitable for the manufacture. These rude constructions had been

the store—houses for the grain, to be used in another form, of the

original inhabitants. Whiskey may be sometimes of inferior quality; but

where the people are generally so good judges of its worth it is not

likely that a bad article will be produced, and it may be observed that

the empyreumatic taste, vulgarly called ‘peat reek,’ is a great defect.

Tarruing dubailt is double distilled, Treasturruing, three times, and when

it is wanted to be still stronger, it is "put four times through," and

called Uisge bea’a ba’ol.

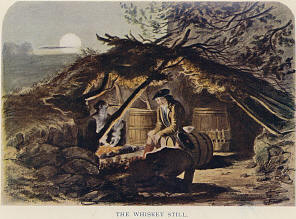

From the nature of the traffic, the

most secluded spot is selected for the plantation of the simple

distillery. Caves in the mountains, coiries or hollows in the upland

heaths, and recesses in the glens, are chosen for the purpose, and they

are, from fear of detection, often abandoned after the first ‘brewst.’ The

print exhibits a Whiskey Still at work in a moonlit night, attended by two

gillean, or youths, and the primitive construction of the apparatus is

sufficiently made out. Into the tub, or vessel, through which the ‘worm,’

or condensing pipe is conveyed, although not seen in the picture, there is

a small rill conducted, which, running through, affords a constant supply

of the cold stream.

National as the love of whiskey

appears to be, it is matter of doubt whether it has been long known to the

Highlanders. Some writers seem to have no doubt that the ancient

Caledonians possessed the art of preparing alcohol; but to arrive at the

distillation of spirits an acquaintance with chemistry is requisite, and

society must be in an advanced state of improvement ere such a manufacture

could be attempted. Writers who have directed their attention to the

subject, maintain that no satisfactory proof can be found of whiskey

having been in use at an earlier period than the beginning of the

fifteenth century. Certain it is, that malt liquor formed the chief

beverage of the old Highlanders, who do not seem to have had so fond a

relish for uisge beatha as their successors, and however useful a dram of

good Glenlivet may be in a northern climate, it does not appear that the

present race are more healthy and hardy than their fathers. General

Stewart gives the evidence of a person who died in 1791, at the age of

that lionn-laidir, strong ale, was the Highland beverage in his youth,

whiskey being procured in scanty portions from the low country; yet Prince

Charles, at Coireairg, in 1745, elated to hear that Cope had declined

battle, ordered whiskey for the common soldiers, to drink the general’s

health, which would prove it to have been then plentiful.

Illicit distillation was at one time

perseveringly carried on throughout Scotland, and whiskey was indeed a

staple commodity. Many depended for payment of their rents upon what they

could make by this means, and landlords had obvious reasons to wink at the

smuggling which prevailed with their knowledge to such an extent among

their tenants; some years ago several justices of the peace in

Aberdeenshire were deprived of their commissions, for stating it as

impossible to carry into effect the stringent acts passed for the

suppression of the illegal practice.

In the fastnesses of the Highland

districts it was difficult to discover the bothies, where the work was

carried on, and prudence often forbade the gauger from attempting a

seizure; but in more accessible parts of the country, his keen search

could only be evaded by the utmost vigilance. In Strathdon, Strathspey,

and neighbouring localities, where a mutual bond of protection exists, it

is the practice, when the exciseman is seen approaching, to display

immediately from the house-top, or a conspicuous eminence, a white sheet,

which being seen by the people of the next ‘town,’ or farm steading, a

similar signal is hoisted, and thus the alarm passes rapidly up the glen,

and before the officer can reach the transgressors of the law, everything

has been carefully removed and so well concealed, that even when positive

information has been given, it frequently happens that no trace of the

work can be found.

The life of a smuggler is harassing,

and the system has a demoralising tendency; from the time he commences

malting he is full of anxiety, and the risk he runs of having the proceeds

of his painful labour captured in its transit to the customer is not the

least of his troubles. Sometimes the low-country people will meet the

Highlanders, and purchase the article at their own risk; but it is

generally taken by the latter to the towns, and they travel frequently in

bodies with horses and carts. Information is often obtained of these

expeditions, and the exciseman intercepts it, taking, if necessary, a

party of soldiers; but sometimes, after a severe encounter, the smugglers

have got off, carrying back a portion of the spirits, and, mayhap, leaving

wounded or dead on both sides. When the party reaches the vicinity of a

town the greatest caution must be observed in going about with the sample

of "the dew," and all sorts of expedients are adopted to convey it, when

sold, to the premises of the buyer.