|

Sir William Johnson thoroughly gained the good graces

of the Iroquois Indians, and by the part he took against the French at

Crown Point and Lake George, in 1755, added to his reputation at home and

abroad. For his services to the Crown he was made a baronet and voted

£5000 by the British parliament, besides being paid £600 per annum as

Indian agent, which he retained, until his death in 1774.

He also received a grant of one hundred

thousand acres of land north of the Mohawk. In 1743 he built Fort Johnson,

a stone dwelling, on the same side of the river, in what is now Montgomery

county. A few miles farther north, in 1764, he built Johnson Hall, a

wooden structure, and there entertained his Indian bands and white

tenants, with rude magnificence, surrounded by his mistresses, both white

and red. He had dreams of feudal power, and set about to realize it. The

land granted to him by the king, he had previously secured from the

Mohawks, over whom he had gained an influence greater than that ever

possessed heretofore or since by a white man over an Indian tribe. The

tract of land thus gained was long known as "Kingsland," or the "Royal

Grant." The king had bound Sir William to him by a feudal tenure of a

yearly rental of two shillings and six pence for each and every one

hundred acres. In the same manner Sir William bound to himself his tenants

to whom he granted leases. In order to secure the greatest obedience he

deemed it necessary to secure such tenants as differed from the people

near him in manners, language, and religion, and that class trained to

whom the strictest personal dependence was perfectly familiar. In all this

he was highly favored. He turned his eyes to the Highlands of Scotland,

and without trouble, owing to the dissatisfied condition of the people and

their desire to emigrate, he secured as many colonists as he desired, all

of whom were of the Roman Catholic faith. The agents having secured the

requisite number, embarked, during the month of August,

1773,

for America.

A journal of the period states that

"three gentlemen of the name of Macdonell, with their families, and

400 Highlanders from the counties

(1) of Glengarry, Glenmorison,

Urquhart, and Strathglass lately embarked for America, having obtained a

grant of land in Albany." [Gentleman's Magazine, Sept. 30, 1773.]

This extract appears to have been

copied from the Courant

of August 28th, which stated they

had "lately embarked for America." This would place their arrival on the

Mohawk some time during the latter part of the following September, or

first of October. The three gentlemen above referred to were Macdonell of

Aberchalder, Leek, and Collachie, and also another, Macdonell of Scotas.

Their fortunes had been shattered in "the 45," and in order to mend them

were willing to settle in America. They made their homes in what was then

Tryon county, about thirty miles from Albany, then called Kingsborough,

where now is the thriving town of Gloversville. To certain families tracts

were allotted varying from one hundred to five hundred acres, all

subjected to the feudal system.

Having reached the places assigned

them the Highlanders first felled the trees and made their rude huts of

logs. Then the forest was cleared and the crops planted amid the stumps.

The country was rough, but the people did not murmur. Their wants were few

and simple. The grain they reaped was carried on horseback along Indian

trails to the landlord’s mills. Their women became accustomed to severe

outdoor employment, but they possessed an indomitable spirit, and bore

their hardships bravely, as became their race. The quiet life of the

people promised to become permanent. They became deeply attached to the

interests of Sir William Johnson, who, by consummate tact soon gained a

mastery over them. He would have them assemble at Johnson Hall that they

might make merry; encourage them in Highland games, and invite them to

Indian councils. Their methods of farming were improved under his

supervision; superior breeds of stock sought for, and fruit trees planted.

But Sir William, in reality, was not with them long; for, in the autumn of

1773, he visited England, returning in the succeeding spring, and dying

suddenly at Johnson Hall on June 24th, following.

Troubles were rising beneath all the

peaceful circumstances enjoyed by the Highlanders, destined to become

severe and oppressive under the attitude of Johnson’s son and son-in-law

who were men of far less ability and tact than their father. The spirit of

democracy penetrated the valley of the Mohawk, and open threats of

opposition began to be heard. The Acts of the Albany Congress of 1774

opened the eyes of the people to the possibilities of strength by united

efforts. Just as the spirit of independence reached bold utterance Sir

William died. He was succeeded in his title, and a part of his estates by

his son John. The dreams of Sir William vanished, and his plans failed in

the hands of his weak, arrogant, degenerate son. Sir John hesitated,

temporized, broke his parole, fled to Canada, returned to ravage the lands

of his countrymen, and ended by being driven across the border.

The death of Sir William made Sir

John commandant of the militia of the Province of New York. Colonel Guy

Johnson became superintendent of Indian affairs, with Colonel Daniel

Claus, Sir William’s son-in-law, for assistant. The notorious

Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) became secretary to Guy Johnson. Nothing but

evil could be predicated of such a combination; and Sir John was not slow

to take advantage of his position, when the war cloud was ready to burst.

As early as March 16, 1775, decisive action was taken, when the grand

jury, judges, justices, and others of Tryon county, to the number of

thirty-three, among whom was Sir John, signed a document, expressive of

their disapprobation of the act of the people of Boston for the

"outrageous and unjustifiable act on the private property of the India

Company," and of their resolution "to bear faith and true allegiance to

their lawful Sovereign King George the Third." [Am. Archives, Fourth

Series, Vol. II. p. 151.] It is a noticeable feature that not one of the

names of Highlanders appears on the paper. This would indicate that they

were not a factor in the civil government of the county.

On May 18, 1775, the

Committee of Palatine District, Tryon county, addressed the Albany

Committee of Safety, in which they affirm:

"This County has,. for a series of

years, been ruled by one family, the different branches of which are still

strenuous in dissuading people from coming into Congressional measures,

and even have, last week, at a numerous meeting of the Mohawk District,

appeared with all their dependants armed to oppose the people considering

of their grievances; their number being so large, and the people unarmed,

struck terror into most of them, and they dispersed. We are informed that

Johnson-Hall is fortifying by placing a parcel of swivel-guns round the

same, and that Colonel Johnson has had parts of his regiment of Militia

under arms yesterday, no doubt with a design to prevent the friends of

liberty from publishing their attachment to the cause to the world.

Besides which we are told that about one hundred and fifty Highlanders,

(Roman Catholicks) in and about Johnstown, are armed and ready to march

upon the like occasion."

In order to allay the feelings

engendered against them Guy Johnson, on May 18th, wrote to the Committee

of Schenectady declaring "my duty is to promote peace," and on the 20th to

the Magistrates of Palatine, making the covert threat "that if the Indians

find their council fire disturbed, and their superintendent insulted, they

will take a dreadful revenge. The last letter thoroughly aroused the

Committee of Tryon county, and on the 21st stated, among other things:

"That Colonel Johnson’s conduct in

raising fortifications round his house, keeping a number of Indians and

armed men constantly about him, and stopping and searching travelers upon

the King’s highway, and stopping our communication with Albany, is very

alarming to this County, and is highly arbitrary, illegal, oppressive, and

unwarrantable; and confirms us in our fears, that his design is to keep us

in awe, and oblige us to submit to a state of Slavery."

On the 23rd the Albany Committee warned Guy Johnson

that his interference with the rights of travelers would no longer

be tolerated. So flagrant had been the conduct of the

John-sons that a sub-committee of the city and

county of Albany addressed a communication on the subject to the

Provincial Congress of New York. On June 2nd

the Tryon County Committee addressed Guy Johnson, in which they affirm "it

is no more our duty than inclination to protect you in the discharge of

. your province," but will not "pass

over in silence the interruption which the people of the Mohawk District

met in their meeting," "and the inhuman treatment of a man whose only

crime was being faithful to his employers." The tension became still more

strained between the Johnsons and patriots during the summer.

The Dutch and German population was chiefly in sympathy

with the cause of America, as were the people generally, in that region,

who did not come under the direct influence of the John-sons. The

inhabitants deposed Alexander White, the Sheriff of Tryon county, who had,

from the first, made himself obnoxious. The first shot, in the war west of

the Hudson, was fired by Alexander White. On some trifling pretext he

arrested a patriot by the name of John Fonda, and committed him to prison.

His friends, to the number of fifty, went to the jail and released him;

and from the prison they proceeded to the sheriff’s lodgings and demanded

his surrender. He discharged a pistol at the leader, but without effect.

Immediately some forty muskets were discharged at the sheriff, with the

effect only to cause a slight wound in the breast. The doors of the house

were broken open, and just then Sir John Johnson fired a gun at the hall,

which was the signal for his retainers and Highland partisans to rally in

arms. As they could muster a force of five hundred men in a short time,

the party deemed it prudent to disperse.

The royalists became more open and bolder in their

course, throwing every impediment in the way of the Safety Committee of

Tryon county, and causing embarrassments in every way their ingenuity

could devise. They called public meetings themselves, as well as to

interfere with those of their neighbors; all of which caused mutual

exasperation, and the engendering of hostile feelings between friends, who

now ranged themselves with the opposing parties.

On October 26th the Tryon County Committee submitted a

series of questions for Sir John Johnson to answer. [Am. Archives, Fourth

Series, Vol. III. p. 1194.] These questions, with Sir John’s answers, were

embodied by the Committee in a letter to the Provincial Congress of New

York, under date of October 28th, as follows:

"As we found our duty and particular reasons to inquire

or rather desire Sir John Jolmson’s absolute opinion and intention of the

three following articles, viz:

1. Whether he would allow that his tenants may form

themselves into Companies, according to the regulations of our Continental

Congress, to the defence of our Country’s cause;

2. Whether he would be willing himself also to

assist personally in the same purpose;

3. Whether he pretendeth a prerogative to our County

Court-House and Jail, and would hinder or interrupt the Committee of our

County to make use of the said publick houses for our want and service in

our common cause;

We have, therefore, from our meeting held yesterday,

sent three members of our Committee with the afore-mentioned questions

contained in a letter to him directed, and received of Sir John,

thereupon, the following answer:

1. That he thinks our requests very unreasonable, as he

never had denied the use of either Court-House or Jail to anybody, nor

would yet deny it for the use which these houses have been built for; but

he looks upon the Court-House and Jail at Johnstown to be his property

till he is paid seven hundred Pounds—which being out of his pocket for the

building of the same.

2. In regard of embodying his tenants into

Companies, he never did forbid them, neither should do it, as they may use

their pleasure; but we might save ourselves that trouble, he being sure

they would not.

3. Concerning himself he declared, that before he would

sign any association, or would lift his hand up against his King, he would

rather suffer that his head shall be cut off. Further, he replied, that if

we would make any unlawful use of the Jail, he would oppose it; and also

mentions that there have many unfair means been used for signing the

Association, and uniting the peo

ple; for he was informed by credible gentlemen in

New-York, that they were obliged to unite, otherwise they could not live

there. And that he was also informed, by good authority, that likewise

two-thirds of the Canajoharie and German Flatts people have been forced to

sign; and, by his opinion, the Boston people are open rebels, and, the

other Colonies have joined them.

Our Deputies replied to his expressions of forcing the

people to sign in our County; that his authority spared the truth, and

it appears by itself rediculous that one-third

should have forced two-thirds to sign. On the contrary, they would prove

that it was offered to any one, after signing, that the regretters could

any time have their names crossed, upon their

requests.

We thought proper to refer these particular inimical

declarations to your House, and would be very glad to get your opinion and

advice, for our further directions. Please, also, to remember what we

mentioned, to you in our former letters, of the inimical and provoking

behaviour of the tenants of said Sir John, which they still continue,

under the authority of said Sir John."

The attitude of Sir John had become such that the

Continental Congress deemed it best, on December 30th

to order General Schuyler "to take the most speedy and effective

measures, for securing the said Arms and Military Stores, and for

disarming the said Tories, and apprehending their chiefs." The action of

Congress was none too hasty; for in a letter from Governor William Trvon

of New York to the earl of Dartmouth, under date of January 5, 1776, he

encloses the following addressed to himself:

"Sir: I hope the occasion and intention of this letter

will plead my excuse for the liberty I take in introducing to your

Excellency the bearer hereof Captain Allen McDonell who will inform you of

many particulars that cannot at this time with safety be committed to

writing. The distracted & convulsed State this unhappy country is now

worked up to, and the situation that I am in here, together with the many

Obligations our family owe to the best of Sovereigns induces me to fall

upon a plan that may I hope be of service to my country, the propriety of

which I entirely submit to Your Excellency’s better judgment, depending on

that friendship which you have been pleased to honour me with for your

advice on and Representation to his Majesty of what we propose. Having

consulted with all my friends in

this quarter, among whom are many old and good Officers, most of whom have

a good deal of interests in their respective neighborhoods, and have now a

great number of men ready to compleat the plan—We must however not think

of stirring till we have a support, & supply of money, necessaries to

enable us to carry our design into execution, all of which Mr. McDonell

who will inform you of everything that has been done in Canada that has

come to our knowledge. As I find by the papers you are soon to sail for

England I despair of having the pleasure to pay my respect to you but most

sincerely wish you an Agreeable Voyage and a happy sight of Your family &

friends. I am.

Your Excellency’s most obedient

humble Servant,

John Johnson."

General Schuvler immediately took active steps to carry

out the orders of Congress, and on January 23, 1776, made a very lengthy

and detailed report to that body. Although he had no troops to carry into

execution the orders of Congress, he asked for seven hundred militia, yet

by the time he reached Caughnawaga, there were nearly three thousand men,

including the Tryon county militia. Arriving at Schenectady, he addressed,

on January 16th, a letter to Sir John Johnson, requesting him to meet him

on the next day, promising safe conduct for him and such person as might

attend him. They met at the time appointed sixteen miles beyond

Schenectady, Sir John being accompanied by some of the leading Highlanders

and two or three others, to whom General Schuyler delivered his terms.

After some difficulty, in which the Mohawk Indians figured as peacemakers,

Sir John Johnson and Allan McDonell (Collachie) signed a paper agreeing

"upon his word and honor immediately deliver up all cannon, arms, and

other military stores, of what kind soever, which may be in his own

possession," or that he may have delivered to others, or that he knows to

be concealed; that "having given his parole of honour not to take up arms

against America," he consents not to go to the westward of the

German-Flats and Kingsland (Highlanders’) District," but to every other

part to the southward he expects the privilege of going; agreed that the

Highlanders shall, "without any kind of exception,

immediately deliver up all arms in their possession, of what kind soever,"

and from among them any six prisoners may be taken, but the same must be

maintained agreeable to their respective rank.

On Friday the 19th General Schulyer marched to

Johnstown, and in the afternoon the arms and military

stores in Sir John’s possession were delivered up. On the next day, at

noon, General Schuyler drew his men up in the street, "and the

Highlanders, between two and three hundred, marched to the front, where

they grounded their arms ;"

when they were dismissed "with an exhortation, pointing out

the only conduct which could insure them protection." On the 21st,

at Cagnhage, General Schuyler wrote to Sir John as follows:

"Although it is a well known fact that all the Scotch

(Highlanders) people that yesterday surrendered arms, had not broad-swords

when they came to the country, yet many of them had, and most of them were

possessed of dirks; and as none have been given up of either, I will

charitably believe that it was rather inattention than a wilful omission.

Whether it was the former or the latter must be ascertained by their

immediate compliance with that part of the treaty which requires that all

arms, of what kind soever, shall be delivered up.

After having been informed by you, at our first

interview, that the Scotch people meant to defend themselves, I was not a

little surprised that no ammunition was delivered up, and that you had

none to furnish them with. These observations were immediately

made by others as well as me. I was too apprehensive of the consequences

which might have been fatal to those people, to take notice of it on the

spot. I shall, however, expect an eclaircissement on this subject, and beg

that you and Mr. McDonell will give it me as soon as may be."

Governor Tryon reported to the earl of Dartmouth,

February 7th that General Schuyler "marched to Johnson Hall the

24th of last month, where Sr John had mustered near Six

hundred men, from his Tenants and neighbours, the majority Highlanders,

after disarming them and taking four pieces of artillery, ammunition and

many Prisoners, with 360 Guineas from Sr John’s Desk, they compelled him

to enter into a Bond in 1600 pound Sterling not to aid the King’s Service,

or to remove within a limited district from his house."

The six of the chiefs of the Highland clan of the

McDonells made prisoners were, Allan McDonell, sen. (Collachie), Allan

McDonell, Jnr., Alexander McDonell, Ronald McDonell, Archibald McDonell,

and John McDonell, all of whom were sent to Reading,

Pennsylvania, with their three servants, and later to Lancaster.

Had Sir John obeyed his parole, it would have saved him

his vast estates, the Highlanders their homes, the effusion of blood, and

the savage cruelty which his leadership engendered. Being incapable of

forecasting the future, he broke his parole of honor, plunged headlong

into the conflict, and dragged his followers into the horrors of war.

General Schuyler wrote him, March 12, 1776, stating that the evidence had

been placed in his hands that he had been exciting the Indians to

hostility, and promising to defer taking steps until a more minute inquiry

could be made he begged Sir John "to be present when it was made," which

would be on the following Monday.

Sir John’s actions were such that it became necessary

to use stringent measures. General Schuyler, on May 14th, issued his

instructions to Colonel Elias Dayton, who was to proceed to Johnstown,

"and give notice to the Highlanders, who live in the vicinity of the town,

to repair to it; and when any number are collected there,

you will send off their baggage, infirm women and children, in wagons."

Sir John was to be taken prisoner, carefully guarded and brought to

Albany, but "he is by no means to experience the least ill-treatment in

his own person, or those of his family." General Schuyler had previously

written (May 10th) to Sir John intimating that he had "acted contrary to

the sacred engagements you lay under to me, and through me to the publick,"

and have "ordered you a close prisoner, and sent down to Albany."

The reason assigned for the removal of the Highlanders as stated by

General Schuyler to Sir John was that "the elder Mr. McDonald (Allan of

Collachie), a chief of that part of the clan of his name now in Tryon

County, has applied to Congress that those people with their families may

be moved from thence and subsisted." To this Sir John replied as follows:

"Johnson Hall, May 18, 1776.

Sir: On my return from Fort Hunter yesterday, I

received your letter by express acquainting me that the elder Mr. McDonald

had desired to have all the clan of his name in the County of Tryon,

removed and subsisted. I know none of that clan but such as are my

tenants, and have been, for near two years supported by me with every

necessary, by which means they have contracted a debt of near two thousand

pounds, which they are in a likely way to discharge, if left in peace. As

they are under no obligations to Mr. McDonald, they refuse to comply with

his extraordinarv request; therefore beg there may be no troops sent to

conduct them to Albany, otherwise they will look upon it as a total breach

of the treaty agreed to at Johnstown. Mrs. McDonald showed me a letter

from her husband, written since he applied to the Congress for leave to

return to their families, in which he mentions that he was told by the

Congress that it depended entirely upon you; he then desired that their

families might be brought down to them, but never mentioned anything with

regard to moving my tenants from hence, as matters he had no right to

treat of. Mrs. McDonald requested that I would inform you that neither

herself nor any of the other families would choose to go down.

I am, sir, your very humble servant,

John Johnson."

Colonel Dayton arrived at Johnstown May 19th,

and as he says, in his report to General John Sullivan, he

immediately sent "a letter to Sir John Johnson, informing him that I had

arrived with a body of troops to guard the Highlanders to Albany, and

desired that he would fix a time for their assembling. When these

gentlemen came to Johnson Hall they were informed by Lady Johnson that Sir

John Johnson had received General Schuyler’s letter by the express; that

he had consulted the Highlanders upon the contents, and that they had

unanimously resolved not to deliver themselves as prisoners, but to go

another way, and that Sir John Johnson had determined to go with them. She

added that, that if they were pursued they were determined to make an

opposition, and had it in their power, in some measure."

The approach of Colonel Dayton’s command caused great

commotion among the inhabitants of Johnstown and vicinity. Sir John

determined to decamp, take with him as many followers as possible, and

travel through the woods to Canada. Lieutenant James Gray, of the 42nd

Highlanders, helped to raise the faithful bodyguard, and all having

assembled at the house of Allen McDonell of Collachie started through the

woods. The party consisted of three Indians from an adjacent village to

serve as guides, one hundred and thirty Highlanders, and one hundred and

twenty others. The appearance of Colonel Dayton was more sudden than Sir

John anticipated. Having but a brief period for their preparation, the

party was but illy prepared for their flight. He did not know whether or

not the royalists were in possession of Lake Champlain, therefore the

fugitives did not dare to venture on that route to Montreal; so they were

obliged to strike deeper into the forests between the headwaters of the

Hudson and the St. Lawrence. Their provisions soon were exhausted; their

feet soon became sore from the rough travelling; and several were left in

the wilderness to be picked up and brought in by the Indians who were

afterwards sent out for that purpose. After nineteen days of great

hardships the party arrived in Montreal in a pitiable condition, having

endured as much suffering as seemed possible for human nature to undergo.

Sir John Johnson and his Highlanders, unwittingly, paid

the highest possible compliment to the kindness and good intentions of the

patriots, when they deserted their families and left them to face the foe.

When the flight was brought to the attention of General Schuyler, he wrote

to Colonel Dayton, May 27, in which he says:

"I am favored with a letter from Mr. Caldwell, in which

he suggests the propriety of suffering such Highlanders to remain at their

habitations as have not fled. I enter fully into his idea; but prudence

dictates that this should be done under certain restrictions. These people

have been taught to consider us in politicks in the same light that

Papists consider Protestants in a religious relation, viz: that no faith

is to be kept with either. I do not, therefore, think it prudent to suffer

any of the men to remain, unless a competent number of hostages are given,

at least five out of a hundred, on condition of being put to death if

those that remain should take up arms, or in any wise assist the enemies

of our country. A small body of troops * * may keep them in awe;

but if an equal body of the enemy should appear, the balance as to

numbers, by the junction of those left, would be against us. I am,

however, so well aware of the absurdity of judging with precision in these

matters at the distance we are from one another, that prudence obliges me

to leave these matters to your judgment, to act as circumstances may

occur."

Lady Johnson, wife of Sir John, was taken to Albany and

there held as a hostage until the following December when she was

permitted to go to New York, then in the hands of the British. Nothing is

related of any of the Highlanders being taken at that time to Albany, but

appear to have been left in peaceable possession of their lands.

As might have been, and perhaps was, anticipated, the

Highland settlement became the source of information and the base of

supplies for the enemy. Spies and messengers came and went, finding there

a welcome reception. The trail leading from there and along the Sacandaga

and through the Adirondack woods, soon became a beaten path from its

constant use. The Highland women gave unstintingly of their supplies, and

opened their houses as places of retreat. Here were planned the swift

attacks upon the unwary settlers farther to the south and west. Agents of

the king were active everywhere, and the Highland homes became one of the

resting places for refugees on their way to Canada. This state of affairs

could not be concealed from the Americans, who, none too soon, came to

view the whole neighborhood as a nest of treason. Military force could not

be employed against women and children (for from time to time nearly all

the men had left), but they could be removed where they would do but

little harm. General Schuyler discussed the matter with General Herkimer

and the Tryon County Committee, when it was decided to remove of those who

remained "to the number of four hundred." A movement of this description

could not be kept a secret, especially when the troops were put in motion.

In March, 1777, General Schuyler had permitted both Alexander and John

MacDonald to visit their families. Taking the alarm, on the approach of

the troops, in May, they ran off to Canada, taking with them the residue

of the Highlanders, together with a few of the German neighbors. The

journey was a very long and tedious one, and very painful for the aged,

the women, and the children. They were used to hardships and bore their

sufferings without Complaint. It was an exodus of a people, whose very

existence was almost forgotten, and on the very lands they cleared and

cultivated there is not a single tradition concerning them.

From papers still in existence, preserved in Series B,

Vol. 158, p. 351, of the Haldeman Papers, it would appear that some of the

families, previous to the exodus, had been secured, as noted in the two

following petitions, both written in either 1779 or 1780, date not given

although first is simply dated "27th July," and second endorsed "27th

July":

"To His Excellency General Haldimand, General and

Commander in Chief of all His Majesty’s Forces in Canada and the Frontiers

thereof,

The memorial of John and Alexander Macdonell, Captains

in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York, humbly sheweth,

That your Memorialist, John Macdonell’s, family are at

present detained by the rebels in the County of Tryon, within the Province

of New York, destitute of every support but such as they may receive from

the few friends to Government in said quarters, in which situation they

have been since 1777.

And your Memorialist, Alexander Macdonell, on behalf of

his brother, Captain Allan Macdonell, of the Eighty-Fourth Regiment: that

the family of his said brother have been detained by the Rebels in and

about Albany since the year 1775, and that unless it was for the

assistance they have met with from Mr. James Ellice, of Schenectady,

merchant, they must have perished.

Your Memorialists therefore humbly pray Your Excellency

will be graciously pleased to take the distressed situation of said

families into consideration, and to grant that a flag be sent to demand

them in exchange, or otherwise direct towards obtaining their releasement,

as Your Excellency in your wisdom shall see fit, and your

Memorialists will ever pray as in duty bound.

John Macdonell,

Alexander Macdonell."

"To the Honourable Sir John Johnson, Lieutenant-Colonel

Commander of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York. The humbel petition of

sundry soldiers of said Regiment sheweth,— That your humble petitioners,

whose names are hereunto subscribed, have families in different places of

the Counties of Albany and Tryon, who have been and are daily ill-treated

by the enemies of Government. Therefore we do humbly pray that Your Honour

would be pleased to procure permission for them to come to Canada,

And your petitioners will ever pray.

John McGlenny, Thomas Ross, Alexander Cameron,

Frederick Goose, Wm. Urchad (Urquhart?), Duncan Mclntire, Andrew

Mileross, Donald McCarter, Allen Grant, Hugh Chisholm, Angus Grant, John

McDonald, Alex. Ferguson, Thomas Taylor, William Cameron, George Murdoff,

William Chession (Chisholm), John Christy, Daniel Campbell, Donald Ross,

Donald Chissem, Roderick McDonald, Alexander Grant.

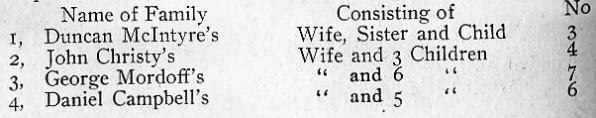

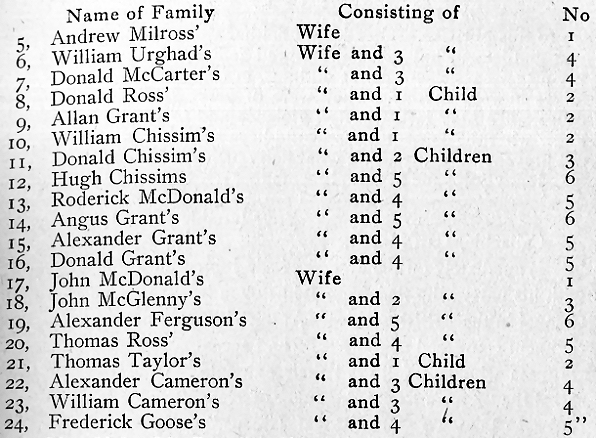

The names and number of each family intended in the

written petition :—

Mrs. Helen MacDonell, wife of Allan, the chief, was

apprehended and sent to Schenectady ,and in 1780 managed to escape, and

made her way to New York. Before she was taken, and while her husband was

still a prisoner of war, she appears to have been the chief person who had

charge of the settlement, after the men had fled with Sir John Johnson. A

letter of hers has been preserved, which is not only interesting, but

throws some light on the action of the Highlanders. It is addressed to

Major Jellis Fonda, at Caughnawaga.

"Sir: Some time ago I wrote you a letter, much to this

purpose, concerning the inhabitants of this Bush being made prisoners.

There was no such thing then in agitation as you was pleased to observe in

your letter to me this morning. Mr. Billie Laird came amongst the people

to give them warning to go in to sign, and swear. To this they will never

consent, being already prisoners of General Schuyler. His Excellency was

pleased by your proclamation, directing every one of them to return to

their farms, and that they should be no more troubled nor molested during

the war. To this they agreed, and have not done anything against the

country, nor intend to, if let alone. If not, they will lose their lives

before being taken prisoners again. They begged the favour of me to write

to Major Fonda and the gentlemen of the committee to this purpose. They

blame neither the one nor the other of you gentlemen, but those

ill—natured fellows amongst them that get up an excitement about nothing,

in order to ingratiate themselves in your favour. They were of very great

hurt to your cause since May last, through violence and ignorance. I do

not know what the consequences would have been to them long ago, if not

prevented. Only think what daily provocation does.

Jenny joins me in compliments to Mrs. Fonda.

I am, Sir,

Your humble servant,

Callachie, 15th March, 1777. Helen McDonell."

Immediately on the arrival of Sir John Johnson in

Montreal, with his party who fled from Johnstown, he was commissioned a

Colonel in the British service. At once he set about to organize a

regiment composed of those who had accompanied him, and other refugees who

had followed their example. This regiment was called the "King’s Royal

Regiment of New York," but by Americans was known as "The Royal Greens,"

probably because the facings of their uniforms were of that color. In the

formation of the regiment he was instructed that the officers of the corps

were to be divided in such a manner as to assist those who were distressed

by the war; but there were to be no pluralities of officers,— a practice

then common in the British army.

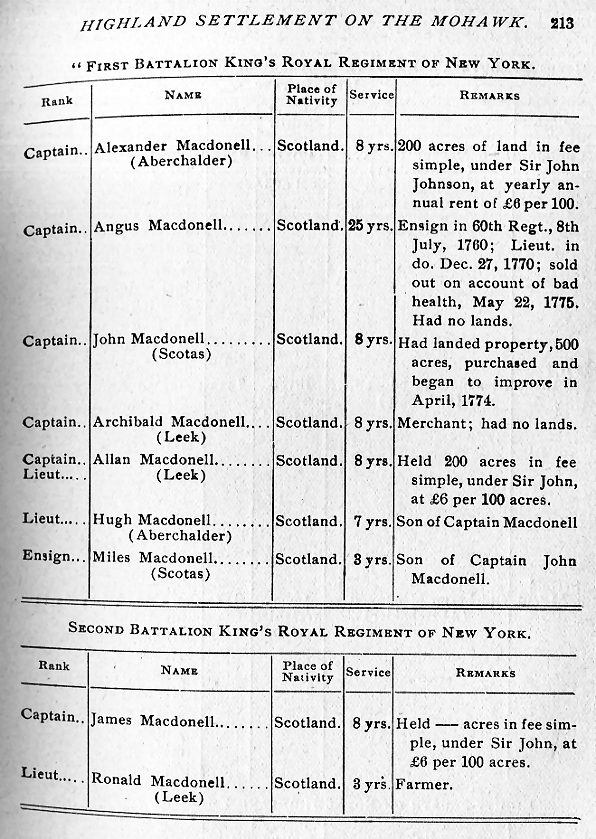

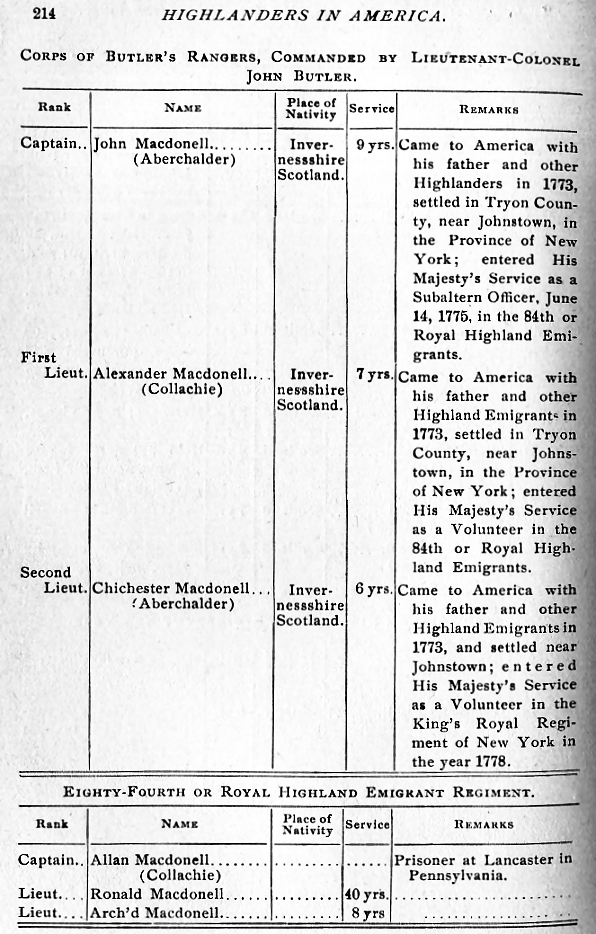

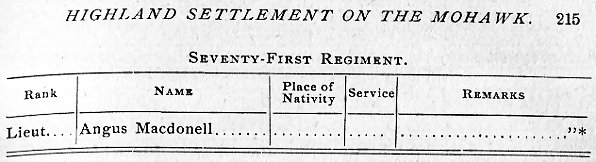

In this regiment, Butler’s Rangers, and the

Eighty-Fourth, or Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment also then raised, the

Highland gentlemen who had, in 1773, emigrated to Tryon county, received

commissions, as well as those who had previously had joined the ranks.

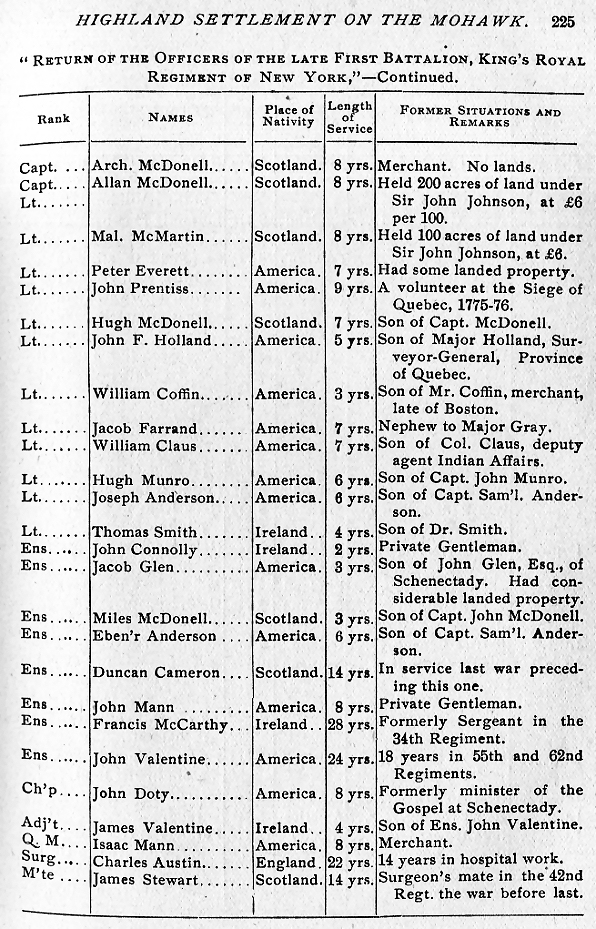

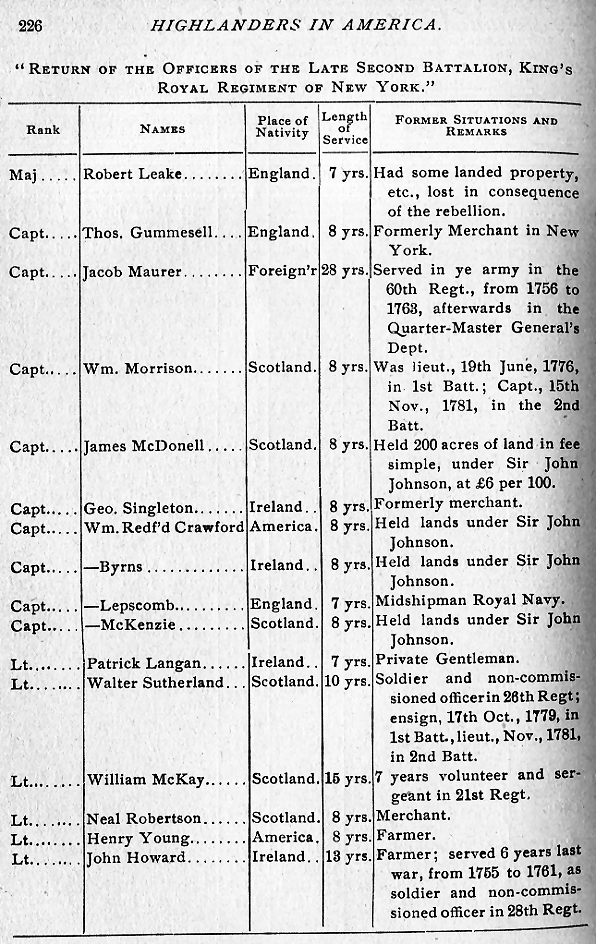

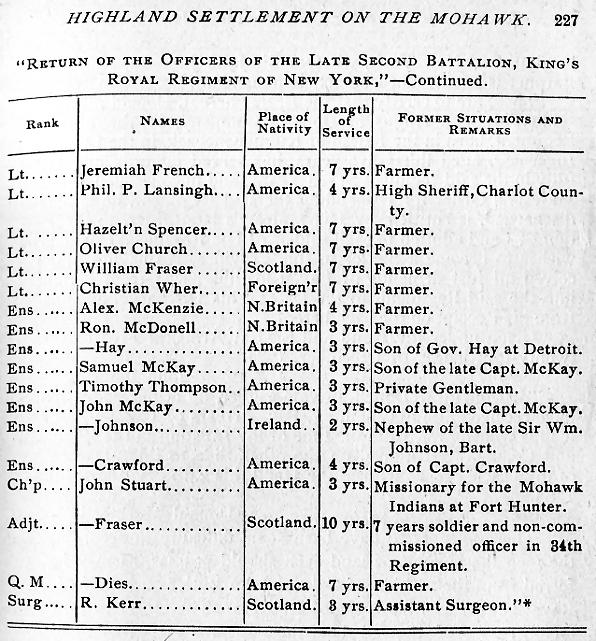

After the war proper returns of the officers were made, and from these the

following tables have been extracted. The number of private soldiers of

the same name are in proportion.

In the month of January, following his flight into

Canada, Sir John Johnson found his way into the city of New York.

From that time he became one of the most bitter and virulent foes of his

countrymen engaged in the contest, and repeatedly became the scourge of

his former neighbors-in all of which his Highland retainers bore a

prominent part. In savage cruelty, together with Butler’s Rangers,

they outrivalled their Indian allies. The aged, the infirm, helpless

women, and the innocent babe in the cradle, alike perished before them. In

all this the MacDonells were among the foremost. Such warfare met the

approval of the British Cabinet, and officers felt no compunction in

relating their achievements. Colonel Guy Johnson writing to lord George

Ger- main, November 11, 1779, not only speaks of the result of his

conference with Sir John Johnson, but further remarks that "there appeared

little prospect of effecting anything beyond harrassing the frontiers with

detached partys. " In all probability none of the official reports related

the atrocities perpetrated under the direction of the minor officers.

Although "The Royal Greens" were largely composed of

the Mohawk Highlanders, and especially all who decamped from Johnstown

with Sir John Johnson, and Butler’s Rangers had a fair percentage of the

same, it is not necessary to enter into a detailed account of their

achievements because neither was essentially Highlanders. Their movements

were not always in a body, and the essential share borne by the

Highlanders have not been recorded in the papers that have been preserved.

Individual deeds have been narrated, some of which are here given.

The Royal Greens and Butler’s Rangers formed a part of

the expedition under Colonel Barry St. Leger that was sent against Fort

Schuyler in order to create a diversion in favor of General Burgoyne’s

army then on its march towards Albany. In order to relieve Fort Schuyler (Stanwix)

General Herkimer with a force of eight hundred was dispatched and, on the

way, met the army of St. Leger near Oriskany, August 6, 1777. On the 3rd

St. Leger encamped before Fort Stanwix, his force numbering sixteen

hundred, eight hundred of whom were Indians. Proper precautions were not

taken by General Herkimer, while every advantage was enforced by his wary

enemy. He fell into an ambuscade, and a desperate conflict ensued. During

the conflict Colonel Butler attempted a ruse-de guerre, by sending,

from the direction of the fort, a detachment of The Royal Greens,

disguised as American troops, in expectation that they might be received

as reenforcements from the garrison. They were first noticed by Lieutenant

Jacob Sammons, who at once notified Captain Jacob Gardenier; but the quick

eye of the latter had detected the ruse. The Greens continued to advance

until hailed by Gardenier, at which moment one of his own men observing an

acquaintance in the opposing ranks, and supposing them to be friends, ran

to meet him, and presented his hand. The credulous fellow was dragged into

their lines and notified that he was a prisoner.

"He did not yield without a struggle; during which

Garde-nier, watching the action and the result, sprang forward, and with a

blow from his spear levelled the captor to the dust and liberated his man.

Others of the foe instantly set upon him, of whom he slew the second and

wounded the third. Three of the disguised Greens now sprang upon him, and

one of his spurs becoming entangled in their clothes, he was thrown to the

ground. Still, contending, however, with almost super-human strength, both

of his thighs were transfixed to the earth by the bayonets of two of his

assailants, while the third presented a bayonet to his breast, as if to

thrust him through. Seizing the bayonet with his left hand, by a sudden

wrench he brought its owner down upon himself, where he held him as a

shield against the arms of the others, until one of his own men, Adam

Miller, observing the struggle, flew to the rescue. As the assailants

turned upon their new adversary, Gardenier rose upon his seat; and

although his hand was severely lacerated by grasping the bayonet which had

been drawn through it, he seized his spear lying by his side, and quick as

lightning planted it to the barb in the side of the assailant with whom he

had been clenched. The man fell and expired—proving to be Lieutenant

McDonald, one of the loyalist officers from Tryon county.

This was John McDonald, who had been held as a hostage

by General Schuyler, and when permitted to return home, helped run off

the remainder of the Highianclers to Canada, as previously noticed.

June 19, 1777, he was appointed captain Lieutenant in The Royal Greens.

During the engagement thirty of The Royal Greens fell near the body of

McDonald. The loss of Herkimer was two hundred killed, exclusive of the

wounded and prisoners. The royalist loss was never given, but known to be

heavy. The Indians lost nearly a hundred warriors among whom were sachems

held in great favor. The Americans retained possession of the field owing

to the sortie made by the garrison of Fort Schuyler on the camp of St.

Leger. On the 22nd St. Leger receiving alarming reports of the advance of

General Arnold suddenly clecamped from before Fort Schuyler, leaving his

baggage behind him. Indians, belonging to the expedition followed in the

rear, tomahawking and scalping the stragglers; and when the army did not

run fast enough, they accelerated the speed by giving their war cries and

fresh alarms, thus adding increased terror to the demoralized troops. Of

all the men that Butler took with him, when he arrived in Quebec he could

muster but fifty. The Royal Greens also showed their numbers greatly

decimated.

Among the prisoners taken by the Americans was Captain

Angus McDonell of The Royal Greens. For greater security he was

transferred to the southern portion of the State. On October 12th

following, at Kingston, he gave the following parole to the authorities:

"1. Angus McDoiiell, lieutenant in the 60th or Royal

American regiment, now a prisoner to the United States of America and

enlarged on my parole, do promise upon my word of honor that I will

continue within one mile of the house of Jacobus Harden— burgh, and in the

town of Hurley, in the county of Ulster; and that I will not do any act,

matter or thing whatsoever against the interests of America; and further,

that I will remove hereafter to such place as the governor of the state of

New York or the president of the Council of Safety of the said state shall

direct, and that I will observe this my parole until released, exchanged

or otherwise ordered.

Angus McDonell."

The following year Captain Angus McDonald and Allen

McDonald, ensign in the same company were transferred to Reading,

Pennsylvania. The former was probably released or exchanged for he was

with the regiment when it was disbanded at the close of the War. What

became of the latter is unknown. Probably neither of them were Sir John

Johnson’s tenants.

The next movement of special importance relates to the

melancholy story of Wyoming, immortalized in verse by Thomas Campbell in

his "Gertrude of Wyoming." Towards the close of

June 1778 the British officers at

Niagara determined to strike a blow at Wyoming, in Pennsylvania. For this

purpose an expedition of about three hundred white men under Colonel John

Butler, together with about five hundred Indians, marched for the scene of

action. Just what part the McDonells took in the Massacre of Wyoming is

not known, nor is it positive any were present.; but belonging to Butler’s

Rangers it is fair to assume that all such participated in those

heartrending scenes which have been so often related. It was a terrible

day and night for that lovely valley, and its beauty was suddenly changed

into horror and desolation. The Massacre of Wyoming stands out in bold

relief as one of the darkest pictures in the whole panorama of the

Revolution.

While this scene was being enacted, active preparations

were pushed by Alexander McDonald for a descent on the New York frontiers.

It was the same Alexander who has been previously mentioned as having been

permitted to return to the Johnstown settlement, and then assisted in

helping the remaining Highland families escape to Canada. He was a man of

enterprise and activity, and by his energy he collected three hundred

royalists and Indians and fell with great fury upon the frontiers, Houses

were burned, and such of the people as fell into his hands were either

killed or made prisoners. One example of the blood thirsty character of

this man is given by Sims, in his "Trappers of New York," as follows:

"On the morning of October 25, 1781, a large body of

the enemy under Maj. Ross, entered Johnstown with several prisoners, and

not a little plunder; among which was a number of human scalps taken the

afternoon and night previous, in settlements in and adjoining the Mohawk

valley; to which was added the scalp of Hugh McMonts, a constable, who was

surprised and killed as they entered Johnstown. In the course of the day

the troops from the garrisons near and militia from the surrounding

country, rallied under the active and daring Willett, and gave the enemy

battle on the Hall farm, in which the latter were finally defeated with

loss, and made good their retreat into Canada. Young Scarsborough was then

in the nine months’ service, and while the action was going on, himself

and one Crosset left the Johnstown fort, where they were on garrison duty,

to join in the fight, less than two miles distant. Between the Hall

and woods they soon found themselves engaged. Crosset after shooting down

one or two, received a bullet through one hand, but winding a handkerchief

around it he continued the fight under cover of a hemlock

stump. He was shot down and killed there, and his

companion surrounded and made

prisoner by a party of Scotch (Highlanders) troops commanded by Captain

McDonald. When Scarsborough was captured, Capt. McDonald was not present,

but the moment he saw him he ordered his men

to shoot him down. Several refused; but three, shall I call them men?

obeyed the dastardly order, and yet he possibly would have survived his

wounds, had not the miscreant in authority cut him down with his own

broad— sword. The sword was caught in its first descent, and the valiant

captain drew it out, cutting the hand nearly in two."

This was the same McDonald who, in 1779, figured in the

battle of the Chemung, together with Sir John and Guy Johnson and Walter

N. Butler.

Just what part the Mohawk Highlanders, if any, had in

the Massacre of Cherry Valley on October 11, 1778, may not be known. The

leaders were Walter N. Butler, son of Colonel John Butler, who was captain

of a company of Rangers, and the monster Brant.

Owing to the frequent depredations made by the Indians,

the Royal Greens, Butler’s Rangers, and the independent company of

Alexander McDonald, upon the frontiers, destroying the innocent and

helpless as well as those who might be found in arms, Congress voted that

an expedition should he sent into the Indian country. Washington detached

a division from the army under General John Sullivan to lay waste that

country. The instructions were obeyed, and Sullivan did not cease until he

found no more to lay waste. The only resistance he met with that was of

any moment was on August 29, 1779, when the enemy hoping to ambuscade the

army of Sullivan, brought on the battle of Chemung, near the present site

of Elmira. There were about three hundred royalists under Colonel John

Butler and Captain Alexander McDonald, assisting Joseph Brant who

commanded the Indians. The defeat was so overwhelming that the royalists

and Indians, in a demoralized condition sought shelter under the walls of

Fort Niagara.

The lower Mohawk Valley having experienced the

calamities of border wars was yet to feel the full measures of suffering.

On Sunday, May 21, 1780, Sir John Johnson with some British troops, a

detachment of Royal Greens, and about two hundred Indians and Tories, at

dead of night fell unexpectedly on Johnstown, the home of his youth.

Families were killed and scalped, the houses pillaged and then burned.

Instances of daring and heroism in withstanding the invaders have been

recorded.

Sir John’s next achievement was in the fall of the same

year, when he descended with fire and sword into the rich settlements

along the Schoharie. He was overtaken by the American force at Klock’s

Field and put to flight.

Sir John Johnson with the Royal Greens, principally his

former tenants and retainers, appear to have been especially stimulated

with hate against the people of their former homes who did not sympathize

with their views. In the summer of 1781 another expedition was secretly

planned against Johnstown, and executed with silent celerity. The

expedition consisted of four companies of the Second battalion of Sir

John’s regiment of Royal Greens, Butler’s Rangers and two hundred Indians,

numbering in all about one thousand men, under the command of Major Ross.

He was defeated at the battle of Johnstown on October 25th. The army of

Major Ross, for four days in the wilderness, on their advance had been

living on only a half pound of horse flesh per man per day; yet they were

so hotly pursued by the Americans that they were forced to trot off a

distance of thirty miles before they stopped,—during a part of the

distance they were compelled to sustain a running fight. They crossed

Canada Creek late in the afternoon, where Walter N. Butler attempted to

rally the men. He was shot through the head by an Oneida Indian, who was

with the Americans. When Captain Butler fell his troops fled in the utmost

confusion, and continued their flight through the night. Without food and

even without blankets they had eighty miles to traverse through the dreary

and pathless wilderness.

On August 6, 1781, Donald McDonald, one of the

Highlanders who had fled from Johnstown, made an attempt upon Shell’s Bush

about four miles north of the present village of Herkimer, at the head of

sixty-six Indians and Tories. John Christian Shell had built a block-house

of his own, which was large and substantial, and well calculated to

withstand a seige. The first story had no windows, but furnished with

loopholes which could be used to shoot through by muskets. The second

story projected over the first, so that the garrison could fire upon an

advancing enemy, or cast missiles upon their heads. The owner had a family

of six sons, the youngest two were twins, and only eight years old. Most

of his neighbors had taken refuge in Fort Dayton; but this settler refused

to leave his home. When Donald McDonald and his party arrived at Shell’s

Bush his brother with his sons were at work in the field; and the

children, unfortunately were so widely separated from their father, as to

fall into the hands of the enemy.

"Shell and his other boys succeeded in reaching their

castle, and barricading the ponderous door. And then commenced the battle.

The beseiged were well armed, and all behaved with admirable bravery; but

none more bravely than Shell’s wife, who loaded the pieces as her husband

and sons discharged them. The battle commenced at two o’clock, and

continued until dark. Several attempts were made by McDonald to set fire

to the castle, but without success; and his forces were repeatedly driven

back by the galling fire they received. McDonald at length procured a

crow-bar and attempted to force the door; but while thus engaged he

received a shot in the leg from Shell’s Blunderbuss, which put him hors

du combat. None of his men being sufficiently near at the moment to

rescue him, Shell, quick as lightning, opened the door, and drew him

within the walls a prisoner. The misfortune of Shell and his garrison was,

that their ammunition began to run low; but McDonald was very amply

provided, and to save his own life, he surrendered his cartridges to the

garrison to fire upon his comrades. Several of the enemy having been

killed and others wounded, they now drew off for a respite. Shell and his

troops, moreover, needed a little breathing time; and feeling assured

that, so long as he had the commanding officer of the beseigers in his

possession, the enemy would hardly attempt to burn the citadel, he ceased

firing. He then went up stairs, and sang the hymn which was a favorite of

Luther during the perils and afflictions of the Great Reformer in his

controversies with the Pope. While thus engaged the enemy likewise ceased

firing. But they soon after rallied again to the fight, and made a

desperate effort to carry the fortress by assault. Rushing up to the

walls, five of them thrust the muzzles of their guns through the

loop-holes, but had no sooner done so, than Mrs. Shell, seizing an axe, by

quick and well directed blows ruined every musket thus thrust through the

walls, by bending the barrels. A few more well-directed shots by Shell and

his sons once more drove the assailants back. Shell thereupon ran up to

the second story, just in the twilight, and calling out to his wife with a

loud voice, informed her that Captain Small was approaching from Fort

Dayton with succors. In yet louder notes he then exclaimed—’Captain Small

march your company round upon this side of the house. Captain Getman, you

had better wheel your men off to the left, and come up upon that side.’

There were of course no troops approaching; but the directions of Shell

were given with such precision, and such apparent earnestness and

sincerity, that the stratagem succeeded, and the enemy immediately fled to

the woods, taking away the twin-lads as prisoners. Setting the best

provisions they had before their reluctant guest, Shell and his family

lost no time in repairing to Fort Dayton, which they reached in

safety—leaving McDonald in the quiet possession of the castle he had been

striving to capture in vain. Some two or three of McDonald’s Indians

lingered about the premises to ascertain the fate of their leader; and

finding that Shell and his family had evacuated the post, ventured in to

visit him. Not being able to remove him, however, on taking themselves

off, they charged their wounded leader to inform Shell, that if he would

be kind to him, (McDonald,) they would take good care of his (Shell’s)

captive boys. McDonald was the next day removed to the fort by Captain

Small, where his leg was amputated; but the blood could not be stanched,

and he died within a few hours. The lads were carried away into Canada.

The loss of the enemy on the ground was eleven killed and six wounded. The

boys, who were rescued after the war, reported that they took twelve of

their wounded away with them, nine of whom died before they arrived in

Canada. McDonald wore a silver-mounted tomahawk, which was taken from him

by Shell. It was marked by thirty scalp-notches, showing that few Indians

could have been more industrious than himself in gathering that

description of military trophies."

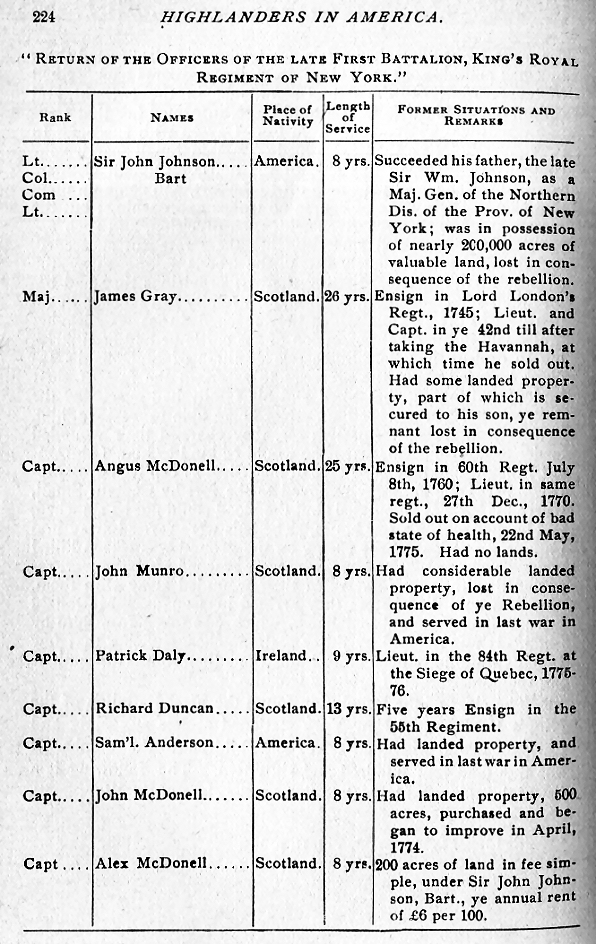

The close of the Revolution found the First Battalion

of the King’s Regiment of New York stationed at Isle aux Noix and Carleton

Island with their wives and children to the number of one thousand four

hundred and sixty-two. The following is a list of the officers of both

Battalions at the close of the War:

The officers and men of the First Battalion, with their

families, settled in a body in the first five townships west of the

boundary line of the Province of Quebec, being the present townships of

Lancaster, Charlottenburgh, Cornwall, Osnabruck and Williamsburgh; while

those of the Second Battalion went farther west to

the Bay of Quinte, in the counties of

Lennox and Prince Edward. Each soldier received a certificate entitling

him to land; of which the following is a copy:

"His Majesty’s Provincial Regiment, called the King’s

Royal

Regiment of New York, whereof Sir John Johnson, Knight

and Baronet is Lieutenant-Colonel, Commandant.

These are to certify that the Bearer hereof, Donald

McDonell, soldier in Capt. Angus McDonell’s Company, of the aforesaid

Regiment, born in the Parish of Killmoneneoack, in the County of

Inverness, aged thirty-five years, has served honestly and faithfully in

the said regiment Seven Years; and in consequence of His Majesty’s Order

for Disbanding the said Regiment, he is hereby discharged, is entitled, by

His Majesty’s late Order, to the Portion of Land allotted to each soldier

of His Provincial Corps, who wishes to become a Settler in this Province,

He having first received all just demands of Pay, Cloathing, &c., from his

entry into the said Regiment, to the Date of his Discharge, as appears

from his Receipt on the back hereof. Given under my Hand and Seal at Arms,

at Montreal, this twenty-fourth Day of December, 1783.

John Johnson."

"I, Donald McDonell, private soldier, do acknowledge

that I have received all my Cloathing, Pay, Arrears of Pay, and all

Demands whatsoever, from the time of my Inlisting in the Regiment and

Company mentioned on the other Side to this present Day of my Discharge,

as witness my Hand this 24th day of December, 1783.

Donald McDonell."

There appears to have been some difficulty in according

to the men the amount of land each, should possess, as may be inferred

from the petition of Colonel John Butler on behalf of The Royal Greens and

his corps of Rangers. The Order in Council, October 22 1788 allowed them

the same as that allotted to the members of the Royal Highland Emigrants.

Ultimately each soldier received one hundred acres on the river front,

besides two hundred at a remote distance. If married he was entitled to

fifty acres more, an additional fifty for every child, Each child, on

coming of age, was entitled to a further grant of two hundred acres.

It is not the purpose to follow these people into their

future homes, for this would be later than the Peace of 1783. Let it

suffice to say that their lands were divided by lot, and into the

wilderness they went, and there cleared the forests, erected their

shanties out of round logs, to a height of eight feet, with a room not

exceeding twenty by fifteen feet.

These people were pre-eminently social and attached to

the manners and customs of their fathers. In Scotland the people would

gather in one of their huts during the long winter nights and listen to

the tales of Ossian and Fingal. So also they would gather in their huts

and listen to the best reciter of tales. Often the long nights would be

turned into a recital of the sufferings they endured during their flight

into Canada from Johnstown; and also of their privations during the long

course of the war. It required no imagination to picture their hardships,

nor was it necessary to indulge in exaggeration. Many of the women,

through the wilderness, carried their children on their backs, the greater

part of the distance, while the men were burdened with their arms and such

goods as were deemed necessary. They endured perils by land and by water;

and their food often consisted of the flesh of dogs and horses, and the

roots of trees. Gradually some of these story tellers varied their tale,

and, perhaps, believed in the glosses.

A good story has gained extensive currency, and has

been variously told, on Donald Grant. He was born at Crasky, Glenmoriston,

Scotland, and was one of the heroes who sheltered prince Charles in the

cave of Corombian, when wandering about, life in hand, after the battle of

Culloden, before he succeeded in effecting his escape to the Outer

Hebrides. Donald, with others, settled in Glengarry, a thousand acres

having been allotted to him. This old warrior, having seen much service,

knew well the country between Johnstown and Canada. He took charge of one

of the parties of refugees in their journey from Schenectady to Canada.

Donald lived to a good old age and was treated with much consideration by

all, especially those whom he had led to their new homes. It was well

known that he could spin a good story equal to the best. As years went on,

the number of Donald’s party rapidly increased, as he told it to

open-mouthed listeners, constantly enlarging on the perils and hardships

of the journey. A Highland officer, who had served in Canada for some

years, was returning home ,and, passing through Glengarry, spent a few

days with Alexander Macdonell, priest at St. Raphael’s. Having expressed

his desire to meet some of the veterans of the war, so that he might hear

their tales and rehearse them in Scotland, that they might know how their

kinsmen in Canada had fought and suffered for the Crown,

the priest, amongst others, took him to see old Donald Grant. The

opportunity was too good to be lost, and Donald told the general in Gaelic

the whole story, omitting no details; giving an account of the number of

men, women and children he had brought with him,

their perils and their escapes, their hardships borne

with heroic devotion; how, when on the verge of starvation, they

had boiled their moccassins and eaten them; how they

had encountered the enemy, the wild beasts and Indians, beaten all off and

landed the multitude safely in Glengarry. The General listened with

respectful attention, and at the termination of the narrative, wishing to

say something pleasant, observed:

"Why, dear me, Donald, your exploits seem almost to

have equalled even those of Moses himself when leading the children of

Israel through the Wilderness from Egypt to the Land of Promise." Up

jumped old Donald. "Moses," exclaimed the veteran with an unmistakable air

of contempt, and adding a double expletive that need not here be repeated,

"Compare ME to Moses! Why, Moses took forty years in

his vain attempts to lead his men over a much shorter distance, and

through a mere trifling wilder-ness in comparison with mine, and he never

did reach his destination, and lost half his army in

the Red Sea. I brought my people here without the loss of a single man."

It has been noted that the Highlanders who settled on

the Mohawk, on the lands of Sir William Johnson, were

Roman Catholics. Sir William, nor his son and successor, Sir John

Johnson, took any steps to procure them a religious teacher in the

principles of their faith. They were not so provided until after the

Revolution, and then only when they were settled on the lands that had

been allotted to them. In 1785, the people themselves took the proper

steps to secure such an one,—and one who was able to speak the Gaelic, for

many of them were ignorant of the English language. In the month of

September, 1786, the ship "McDonald," from Greenock, brought Reverend

Alexander McDonell, Scotus, with five hundred emigrants from Knoydart, who

settled with their kinsfolk in Glengarry, Canada. |