|

The fruitful soil of America,

together with the prospects of a home and an independent living, was

peculiarly adapted to awaken noble aspirations in the breasts of those who

were interested in the welfare

of that class whose condition needed a radical enlargement. Among this

class of Nature’s noblemen there is no name deserving of more praise than

that of Lauchlan Campbell. Although his name, as well as the migration of

his infant colony, has gone out of Islay ken, where he was born, yet his

story has been fairly well preserved in the annals of the province of New

York. It was first publicly made known by William Smith, in

his "History of New York."

Lauchlan Campbell was possessed of a

high sense of honor and a good understanding; was active, loyal, of a

military disposition, and, withal, strong philanthropic inclinations. By

placing implicit confidence in

the royal governors of New York,

he fell a victim to their roguery, deception and heartlessness, which

ultimately crushed him and left him almost penniless. The story has been

set forth in the following memorial, prepared by his son:

"Memorial of Lieutenant Campbell to

the Lords of Trade. To the Right Honourable

the

Lords Commissioners of Trade, &c. Memorial of Lieut. Donald Campbell of

the Province of New York Plantation. Humbly Showeth,

That

in the year 1734 Colonel Cosby being

then Governor of the Province of New York by and with the advice and

assent of his Council published a printed Advertisement for encouraging

the Resort of Protestants from Europe to settle upon the Northern Frontier

of the said Province (in the route from Fort Edward to Crown Point)

promising to each family two hundred acres of unimproved land out of

100,000 acres purchased from the

Indians, without any fee or expenses whatsoever, except a very moderate

charge for surveying & liable only to the King’s Quit Rent of one shilling

and nine pence farthing per hundred acres, which settlement would at that

time have been of the utmost utility to the Province & these proposals

were looked upon as so advantageous, that they could not fail of having a

proper effect.

That these Proposals

in 1737,

falling into the hands of Captain Lauchlin Campbell of the island of Isla,

he the same year went over to North America, and passing through the

Province of Pennsilvania where he rejected many considerable offers that

were made him, he proceeded to New York, where, tho’ Governor Cosby was

deceased, George Clarke Esqr. then Governor, assured him no part of the

lands were as yet granted; importuned him & two or three persons that went

over with him to go up and visit the lands, which they did, and were very

kindly received and greatly caressed by the Indians. On his return to New

York he received the most solemn promises that he should have a thousand

acres for every family that he brought over, and that each fam ily should

have according to their number from five hundred to one hundred and fifty

acres, but declined making any Grant till the Families arrived, because,

according to the Constitution of that Government, the names of the

settlers were to be inserted in that Grant. Captain Campbell accordingly

returned to Isla, and brought from thence at a very large expense, his own

Family and Thirty other Families, making in all, one hundred and

fifty-three Souls. He went again to visit the lands, received all possible

respect and kindness,

from the Government, who proposed an old

Fort Anna to be repaired, to cover the new settlers from the French

Indians. At the same time, the People of New York proposed to maintain the

people already brought, till Captain Campbell could return and bring more,

alledging that it would be for the interest of the Infant Colony to settle

upon the lands in a large Body; that, covered by the Fort, and assisted by

the Indians, they might be less liable to the Incursions of Enemies.

That to keep up the spirit of the

undertaking, Governor Clarke, by a writing bearing date the 4th day of

December, 1738, declared his having promised Captain Campbell thirty

thousand acres of land at Wood Creek, free of charges, except the expense

of surveying & the King’s Quit Rent in consideration of his having already

brought over thirty families who according to their respective numbers in

each family, were to have from one hundred and fifty to five hundred

acres. Encouraged by this declaration, he departed

in the same month for Isla, and in August,

1739, brought over Forty Families more, and under the Faith of the said

promises made a third voyage, from which he returned in November, 1740,

bringing with him thirteen Families the whole making

eighty-three Families, composed of Four Hundred and Twenty Three Persons,

all sincere and loyal Protestants, and very capable of forming a

respectable Frontier for the security of the Province, But after all these

perilous and expensive voyages, and tho’ there wanted but Seventeen

Families to complete the number for which he had undertaken, he found no

longer the same countenance or protection but on the contrary it

was insinuated to him that he could have no land either for

himself or the people, but upon conditions in direct violation of the

Faith of Government. and detrimental to the

interests of those who upon his assurances had accompanied him into

America. The people also were reduced to demand separate Grants for

themselves, which upon large promises some of them did, yet more of them

never had so much as a foot of land, and many listed themselves to join

the Expedition to Cuba.

That Captain Campbell having disposed of his whole

Fortune in the Island of Isla, expended the far greatest part of it from

his confidence in these fallacious promises found himself at length

constrained to employ the little he had left in the

purchase of a small farm seventy miles north of New

York for the subsistence of himself and his Family consisting of three

sons and three daughters. He went over again into Scotland in 1745,

and having the command of a Company of the Argyleshire men,

served with Reputation under his Royal Highness the Duke, against the

Rebels. He went back to America in 1747 and not

longer after died of a broken heart, leaving behind him the six children

before mentioned of whom your Memoralist is the eldest, in very narrow and

distressed circumstances."

All these facts are briefly commemorated by Mr. Smith

in his History of the Colony of New York, page 179,

where are some severe, though just strictures on the behavior of those in

power towards him and the families he brought with him, and the loss the

Province sustained by such behavior towards them.

That at the Commencement of the present War, your

Memoralist and both his brothers following their Father’s principles in

hopes of better Fortune entered into the Army & served in the Forty

Second, Forty Eighth and Sixtieth Regiments of Foot during the whole War,

at the close of which your Memoralist and his brother George were reduced

as Lieutenants upon half pay, and their youngest Brother still

continues in the service ; the small Farm purchased by

their father being the sole support of themselves and three sisters till

they were able to provide for themselves in the manner before mentioned,

and their sisters are now married & settled

in the Province of New York.

That after the conclusion of the Peace, your Memoralist

considering the number of Families dispersed through the Province which

came over with his Father, and finding in them a general disposition to

settle with him on the lands originally promised them, if they could be

obtained, in the month of February, 1763, petitioned

Governor Monckton for the said lands but was able only to procure a Grant

of ten thousand acres, (for obtaining which, he disbursed in

Patent and other fees, the sum of two hundred Guineas), the

people in Power alledging that land was now at a far greater value

than at the time of your Memoralist’s Father’s coming into

the Province, and even this upon the common condition of settling ten

Families upon the said lands and paying a Quit Rent to the Crown.

Part however of the People who had promised to settle with

your Memoralist in case he had prevailed, were drawn to petition for lands

to themselves, which they obtained, tho’ they never

could get one foot of land before, which provision

of lands as your Memoralist apprehends, ought in

Equity to be considered as an obligation on the Province to perform, so

far as the number of those Families goes, the Conditions stipulated with

his Father, as those Families never had come into & consequently could not

now be remaining in the Province, if he had not persuaded them to

accompany him, & been at a very large expence in transporting them

thither.

That there are still very many of these Families who

have no land and would willingly settle with your Memoralist. That there

are numbers of non commissioned Officers and Soldiers of the Regiments

disbanded in North America who notwithstanding His Majesty’s gracious

Intentions are from many causes too long to trouble your Lordship with at

present without any settlement provided for them, and that there are also

many Families of loyal Protestants in the Islands and other parts of North

Britain which might be induced by reasonable proposals and a certainty of

their being fulfilled, to remove into the said

Province, which would add greatly to the strength, security and opulence

thereof, and be in all respects faithful and

serviceable subjects to His Majesty.

That the premisses considered,

particularly the long scene of hardships to which your Memoralist’s Family

has been exposed, for Twenty Six years, in

consideration of his own and his Brothers’ services, & the perils to which

they have been exposed during the long and fatiguing War, and the Prospect

he still has of contributing to the settlement of His Majesty’s unimproved

Country, your Memoralist humbly prays that Your Lordships would direct the

Government of New York to grant to him the said One

Hundred thousand Acres, upon his undertaking to settle One Hundred or One

Hundred and Fifty Families upon the same within the space of Three years

or such other Recompence or Relief as upon mature Deliberation on the

Hardships and Sufferings which his Father and his Family have for so many

years endured, & their merits, in respect to the Province of New York

which might be incontestably proved, if it was not universally

acknowledged, may in your great Wisdom be thought to deserve.

And your Memoralist; &c., &c., &c.* ["

Documentary and Colonial History of New York," Vol. VII, p. 630.

Should 1763 be read for 1764?]

May, 1764."

It was the policy of the home government to settle as

rapidly as possible the wild lands; not so much for the purpose of

benefiting the emigrant as it was to enhance the king’s exchequer. The

royal governors apparently held out great inducements to the settlers, but

the sequel always showed that a species of blackmail or tribute must be

paid by the purchasers before the lands were granted. The governor was one

thing to the higher authorities, but far different to those from whom he

could reap advantage. The seeming disinterested motives may be thus

illustrated:

Under date of New York, July

26, 1736, George Clarke,

lieutenant governor of New York, writes to the duke of Newcastle, in which

he says, it was principally "To augment his Majesty’s Quit rents that I

projected a Scheme to settle the Mohacks Country in this Province, which I

have the pleasure to hear from Ireland and Holland is like to succeed. The

scheme is to give grants gratis of an hundred thousand acres of land to

the first five hundred protestant familys that come from Europe in two

hundred acres to a family, these being settled will draw thousands after

them, for both the situation and quantity of the Land are much preferable

to any in Pensilvania, the only Northern Colony to which the Europeans

resort, and the Quit rents less. Governor Cosby sent home the proposals

last Summer under the Seal of the Province, and under his and the

Council’s hands, but it did not reach Dublin till the last day of March;

had it come there two months sooner I am assured by a letter which I

lately received, directed to Governor Cosby, that we should have had two

ships belonging to this place (then lying there) loaded with people but

next year we hope to have many both from thence and Germany. When the

Mohocks Country is settled we shall have nothing to fear from Canada."

The same, writing to the Lords of Trade, under date of

New York, June 15; 1739, says:

"The lands whereon the French propose to settle were

purchased from Indian proprietors (who have all along been subject to and

under the protection of the Crown of England) by one Godfrey Dellius and

granted to him by patent under the seal of this province in the year 1696,

which grant was afterwards resumed by act of Assembly whereby they became

vested in the Crown; on part of these lands I proposed to settle some

Scotch Highland familys who came hither last year, and they would have

been now actually settled there, if the Assembly would have assisted them,

for they are poor and want help; however as I have promised them lands

gratis, some of them about three weeks ago went to view that part of the

Country, and if they like the lands I hope they will accept my offer (if

the report of the French designs do not discourage them:) depending upon

the voluntary assistance of the people of Albany whose more immediate

interest it is to encourage their settlement in that part of the country."

That Captain Campbell would have secured the lands

there can be no question had he complied, with Governor Clarke’s demands,

although said demands were contrary to the agreement. Private faith and

public honor demanded the fair execution of the project, which had been so

expensive to the undertaker, and would have added greatly to the benefit

of the colony. The governor would not make the grant unless he should have

his fees and a share of the land.

The quit rent in the province of New York was fixed at

two shillings six pence for every one hundred acres. The fees for a grant

of a thousand acres were as follows: To the governor, $31.25; secretary of

state, $10; clerk of the council, $10 to $15;

receiver general, $14.37; attorney general, $7.50; making a

total of about $75, besides the cost of survey. This amount does not

appear to be large for the number of acres, yet it must be considered that

land was plenty, but money very scarce. There were thousands of

substantial men who would have found it exceedingly difficult to raise the

amount in question.

It is possible that Captain Campbell could not have

paid this extortion even if he had been so disposed; but being

high-spirited, he resolutely refused his consent. The governor, still

pretending to be very anxious to aid the emigrants, recommended the

legislature of the province to grant them assistance; but, as usual, the

latter was at war with the governor, and refused to vote money to the

Highlanders, which they suspected, with good reason, the latter would be

required to pay to the colonial officers for fees.

Not yet discouraged, Captain Campbell determined to

exhaust every resource that justice might be done to him. His next step

was to appeal to the legislature for redress, but it was in vain; then he

made an application to the Board of Trade, in England, which had the power

to rectify the wrong. Here he had so many difficulties to contend with

that he was forced to leave the colonists to themselves, who soon after

separated. But all his efforts proved abortive.

The petition of Lieutenant Donald Campbell, though

courteously expressed, and eminently just, was rejected. It was claimed

that the orders of the English government positively forbade the granting

of over a thousand acres to any one person; yet that thousand acres was

denied him.

The injustice accorded to Captain Campbell was more or

less notorious throughout the province. It was generally felt there had

been bad treatment, and there was now a disposition on the part of the

colonial authorities to give some relief to his sons and daughters.

Accordingly, on November 11, 1763, a grant of ten thousand acres, in the

present township of Greenwich, Washington county, New York, was made to

the three brothers, Donald, George and James, their three sisters and four

other persons, three of whom were also named Campbell.

The final success of the Campbell family in obtaining

redress inspired others who had belonged to the colony to petition for a

similar recompense for their hardships and losses. They succeeded in

obtaining a grant of forty-seven thousand, four hundred and fifty acres,

located in the present township of Argyle, and a small part of Fort Edward

and Greenwich, in the same county.

On March 2, 1764, Alexander McNaughton and one

hundred and six others of the original Campbell emigrants and their

descendants, petitioned for one thousand acres to be granted to each of

them:

"To be laid out in a single tract between the head of

South bay and Kingsbury, and reaching east towards New Hampshire and

westwardly to the mountains in Warren county. The committee of the council

to whom this petition was referred reported May 21, 1764, that the tract

proposed be granted, which was adopted, the council specifying the amount

of land each individual of the petitioners should receive, making two

hundred acres the least and six hundred the most that anyone should

obtain. Five men were appointed as trustees, to divide and distribute the

land as directed. The same instrument incorporated the tract into a

township, to he called Argyle, and should have a supervisor, treasurer,

collector, two assessors, two overseers of highways, two overseers of the

poor and six constables, to be elected annually by the inhabitants on the

first day of May. The patent, similar to all others of that period, was

subject to the following conditions:

An annual quit rent of two shillings and six pence

sterling on every one hundred acres, and all mines of gold and silver, and

all pine trees suitable for masts for the royal navy, namely, all which

were twenty-four inches from the ground, reserved to the crown." [On

record in library at Albany in " Patents," Vol. IV, pp. 3.17. ]

The land thus granted lies in the central part of

Washington county, with a broken surface in the west and great elevations

and ridges in the east. The soil is rich and the whole well watered.

The trustees were vested with the power to

execute title deeds to such of the grantees, should they claim the lands,

the first of which were issued during the winter and spring of 1764—5 by

Duncan Reid, of the city of Yew York,

gentleman; Peter Middleton, of same city,

physician; Archibald Campbell,

of same city, merchant Alexander

McNaughton, of Orange county, farmer: and Neil

Gillaspie, of Ulster county, farmer, of the one part, and the grantees of

the other part.

While the application for the grant was yet pending,

the petitioners greatly exalted over their future prospects, evolved a

grand scheme for the survey of the prospective lands, which should include

a stately street from the banks of the Hudson river on the east through

the tract, upon, which

each family should have a town lot, where he might not only enjoy the

protection of near neighbors, but also have that companionship of which

the Highlander is so particularly fond. In the rear of these town lots

were to be the farms, which in time were to be occupied by tenants. The

surveyors, Archibald Campbell, of Raritan, New Jersey, and Christopher

Yates, of Schenectady, who began their labors June

19, 1764, were instructed to lay off the land

as planned, the street to extend from east to west, twenty-four rods wide

and extending through the width of the grant as near the center as

practicable, and to set aside a glebe lot for the benefit of the school

master and the minister. North and south of the street, and bordering on

it, the surveyors laid off lots running back one hundred and eighty rods,

varying in width so as to contain from twenty to sixty acres. These lots

were numbered, making in all one hundred and forty-one, seventy-two being

on the south side of the street, and the remainder on the north. The farms

were also numbered, also making one hundred and forty-one.

In the plan no allowance had been made for the rugged

nature of the country, and consequently the magnificent street was located

over hills whose proportions prevented its use as a public highway, while

some of the lots were uninhabitable.

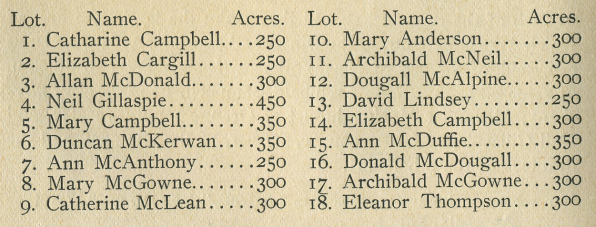

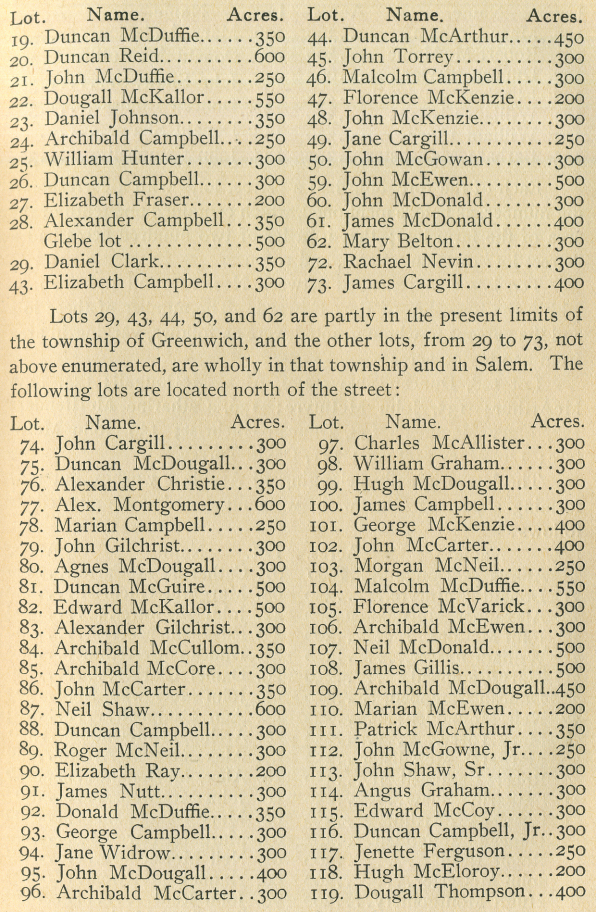

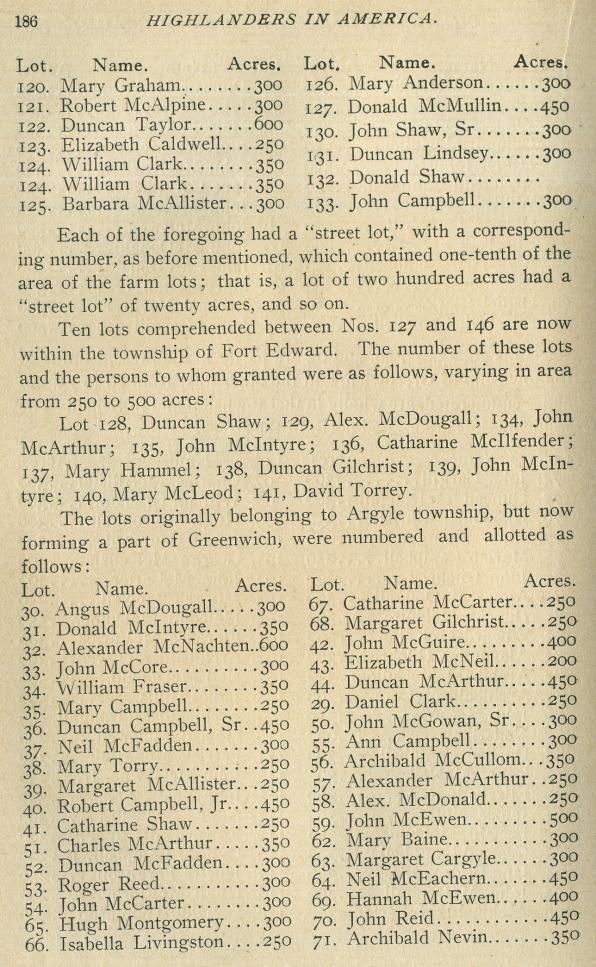

The following is a list of the grantees, the number of

the lot and its contents being set opposite the name:

Many of the grantees immediately took possession of the

lands alloted to them; but others never took advantage of their claims,

which, for a time, were left unoccupied, and then passed into the hands of

others, who generally were left in undisputed possession. This state of

affairs, in connection with the large size of the lots, had the effect of

retarding the growth of that district.

Before the arrival of the settlers, a desperado, named

Rogers, had taken possession of a part of the lands on the Batten Kill. He

warned the people off, making various threats; but the High-landers

knowing their titles were perfect, disregarded the menace, and set about

industriously clearing up their lands and erecting their houses. One day,

when Archibald Livingston was away, his wife was forcibly carried off by

Rogers, and set down outside the limits of the claim, who also proceeded

to remove the furniture from the premises. He was arrested by Roger Reid,

the constable, and brought before Alexander McNaughton, the justice, which

constituted the first civil process ever served in that county. Rogers did

not submit peaceably to be taken, but defended himself with a gun, which

Joseph McCracken seized, and in his endeavor to wrest it from the hands of

the ruffian, he burst the buttons from off the waist-bands of his

pantaloons, which, as he did not wear suspenders, slipped over his feet.

The little son of Rogers, fully taking in the situation, ran up and bit

McCracken, which, however, did not cause him to desist from his purpose.

Rogers was conveyed to Albany, after which all trace of him has been lost.

The township of Argyle, embracing what is now both

Argyle and Fort Edward, was organized in 1771. The record of the first

meeting bears date April 2, 1771, and was called for the purpose of

regulating laws and choosing officers. It was called by virtue of the

grant in the Argyle patent. The officers elected were:

supervisor, Duncan Campbell, who continued until 1781,

and was then succeeded by Roger Reid; town clerk, Archibald Brown,

succeeded in 1775 by Edward Patterson, who, in turn, was succeeded in 1778

by John McNeil, and he by Duncan Gilchrist, in 1780; collector, Roger

Reid, succeeded in 1778 by Duncan McArthur, and the latter in 1781 by

Alexander Gilchrist; assessors, Archibald Campbell and Neal Shaw;

constables, John Offery, John McNiel; poor-masters, James Gilles,

Archibald McNiel; road-masters, Duncan Lindsey, Archibald Campbell; fence

viewers, Duncan McArthur, John Gilchrist.

The following extracts from township records are not

without interest:

1772.—"All men from sixteen to sixty years old to work

on the roads this year. Fences must be four feet and a half high."

1776.—"Duncan Reid is to be constable for the south

part of the patent and Alexander Gillis for the north part; George Kilmore

and James Beatty for masters. John Johnson was chosen a justice of the

peace."

1781 .—"Alexander McDougall and Duncan Lindsey were

elected tithing men."

In order to make the laws more efficient, on March 12,

1772, the county of Charlotte was struck off from Albany, which was the

actual beginning of the present county of Washington. As Charlotte county

had been named for the consort of George III. and as his troops had

devastated it during the Revolution, the title was not an agreeable one,

so the state legislature on April 2,

1784, changed it to Washington, thus giving it the most honored

appellation known in the annals of American history.

For several years after 1764 the colony on the east,

and in what is now Hebron township, was augmented by a number of

discharged Highland soldiers, mostly of the 77th Regiment, who settled on

both sides of the line of the township. It is a noticeable fact that in

every case these settlers were Scotch Highlanders. They had in all

probability been attracted to this spot partly by the settlement of the

colony of Captain Lachlan Campbell, and partly by that of the Scotch-Irish

at New Perth (Salem), which has been noted already in its proper

connection. These additional settlers took up their claims, owing to a

proclamation made by the king, in October, 1763, offering land in America,

without fees, to all such officers and soldiers who had served on that

continent, and who desired to establish their homes there.

Nothing shows more clearly than this proclamation the

lofty position of an officer in the British service at that time as

compared with a private. A field officer received four thousand acres; a

captain three thousand; a lieutenant, or other subaltern commissioned

officer, two thousand; a non-commissioned officer, whether sergeant or

corporal, dropped to two hundred acres, while the poor private was put off

with fifty acres. Fifty acres of wild land, on the hill-sides of

Washington County, was not an extravagant reward for seven years’ service

amidst all the dangers and horrors of French and Indian warfare.

Many of these grants were sold by the soldiers to their

countrymen. Their method of exchange was very simple. The corporal and

private would meet by the roadside, or at a neighboring ale-house, and

after greeting each other, the American land would immediately be the

subject for barter. The private, who may be called Sandy, knew his fifty

acres was not worth the sea-voyage, while Corporal Donald, having already

two hundred, might find it profitable to emigrate, provided he could add

other tracts. After the preliminaries and the haggling had been gone

through with, Donald would draw out his long leather purse and count down

the amount, saying:

"There, mon; there’s your siller."

The worthy Sandy would then dive into some hidden

recess of his garments and bring forth his parchment, signed in the name

of the king by "Henry Moore, baronet, our captain-general and

governor-in-chief, in and over our province of New York, and the lands

depending thereon, in America, chancellor and vice-admiral of the same."

This document would be promptly handed to the purchaser, with the

declaration,

‘An’ there’s your land, corporal."

Many of the soldiers never claimed their lands, which

were eventually settled by squatters, some of whom remained thereon so

long that they or their heirs became the lawful owners.

The famous controversy concerning the "New Hampshire

grants," affected the Highland settlers; but the more exciting events of

the wrangle took place outside the limits of Washington County, and

consequently the Highland settlement. This controversy, which was carried

on with acrimonious and warlike contention arose over New York’s

officials’ claim to the possession of all the land north of the

Massachusetts line lying west of the Connecticut river. In 1751 both the

governors of New York and New Hampshire

presented their respective claims to the territory in dispute to the Lords

of Trade in London. The matter was finally adjusted in 1782, by New York

yielding her claim.

In 1771 there were riots near the southern boundary of

Hebron township, which commenced by the forcible expulsion of Donald

Mclntire and others from their lands, perpetrated by Robert Cochran and

his associates. On October 29th, same year, another serious riot

took place. A warrant was issued for the offenders by Alexander McNaughton,

justice of the peace, residing in Argyle. Charles Hutchison, formerly a

corporal in Montgomery’s Highlanders, testified that Ethan Allen

(afterwards famous), and eight others, on the above date, came to his

residence, situated four miles north of New Perth, and began to demolish

it. Hutchison requested them to stop, but they declared that they would

make a burnt offering to the gods of this world by burning the logs of

that house. Allen and another man held clubs over Hutchison’s head,

ordered him to leave the locality, and declared that, in case he returned,

he should be worse treated. Eight or nine other families were driven from

their homes, in that locality, at the same time, all of whom fled to New

Perth, where they were hospitably received. The lands held by these exiled

families had been wholly improved by themselves. They were driven out by

Allen and his associates because they were determined that no one should

build under a New York title east of the line they had established as the

western boundary.

Bold Ethan Allen was neither to be arrested nor

intimidated by a constable’s warrant. Governor Tryon of New York offered

twenty pounds reward for the arrest of the rioters, which was as

inefficient as esquire McNaughton’s warrant.

The county of Washington was largely settled by people

from the New England states. The breaking out of the Revolutionary War

found these people loyal to the cause of the patriots. The Highland

settlements were somewhat divided, but the greater part allied themselves

with the cause of their adopted country.

Those who espoused the cause of the king, on account of

the atrocities committed by the Indians, were forced to flee, and never

returned save in marauding bands. There were a few, however, who kept very

quiet, and were allowed to remain unmolested.

There were no distinctive Highland companies either in

the British or Continental service from this settlement. A company of

royalists was secretly formed at Fort Edwards, under David Jones

(remembered only as being the betrothed of the lovely but unfortunate Jane

McCrea), and these joined the British forces, There were five companies

from the county that formed the regiment under Colonel Williams, one of

which was commanded by Captain Charles Hutchison, the Highland corporal

whom Ethan Allen had mobbed in 1771 In this company of fifty-two men it

may be reasonably supposed that the greater number were the sons of the

emigrants of Captain Lauchlan Campbell.

The committee of Charlotte county, in September 21,

1775, recommended to the Provincial Congress, that the following named

persons, living in Argyle, should be thus commissioned:

Alexander Campbell, captain; Samuel Pain, first

lieutenant; Peter Gilchrist, second lieutenant; and John McDougall,

ensign.

Captain Joseph McCracken, on the arrival of Burgoyne,

built a fort at New Perth, which was finished on July 26th, and called

Salem Fort.

Donald, son of Captain Lauchlan Campbell, espoused the

cause of the people, but his two brothers sided with the British. Soon

after all these passed out of the district, and their whereabouts became

unknown.

The bitter feelings engendered by the war was also felt

in the Highland settlement, as may be instanced in the following

circumstance preserved by S. D. W. Bloodgood : [The

Sexagenary, p. 110.]

"When Burgoyne found that his boats were not safe, and

were in fact much nearer the main body of our army than his own, it became

necessary to land his provisions, of which he had already been short for

many weeks, in order to prevent his being actually starved into

submission. This was done under a heavy fire from our troops. On one of

these occasions a person by

name of Mr. —, well

known at Salem, and a foreigner by birth, and who

had at the very time a son in the British army,

crossed the river at De Ruyter’s, with a person by name of McNeil; they

went in a canoe, and arriving opposite to the place intended, crossed over

to the western bank, on which a redoubt called Fort Lawrence had been

placed. They crawled up the bank with their arms in their hands, and

peeping over the upper edge, they saw a man in a blanket coat loading a

cart. They instantly raised their guns to fire, an action more savage than

commendable. At the moment the man turned so as to be more plainly seen,

when bid M— said to his companion, ‘Now that’s my own son Hughy; but I’m

dom’d for a’ that if I sill not gie him a shot.’ He then actually fired at

his own son, as the person really proved to be, but happily without

effect. Having heard the noise made by their conversation and the cocking

of the pieces, which the nearness of his position rendered perfectly

practicable, he ran round the cart, and the ball lodged in the felly of

the wheel. The report drew the attention of the neighboring guards, and

the two marauders were driven from their lurking place. While retreating

with all possible speed, McNeil was wounded in the shoulder, and, if

alive, carries the wound about with him to this day. Had the ball struck

the old Scotchman, it is questionable whether any one would have

considered it more than even handed justice commending the chalice to his

own lips."

A map of Washington County would show that it was on

the war path that led to some terrible conflicts related in American

history. Occupying a part of the territory between the Hudson and the

northern lakes, it had borne the feet of warlike Hurons, Iroquois,

Canadians, New Yorkers, New Englanders, French, English, Continentals and

Hessians, who proceeded in their mission of destruction and vengeance. As

the district occupied by the Highlanders was close to the line of

Burgoyne’s march, it experienced the realities of war and the tomahawk of

the merciless savage. How terrible was the work of the ruthless savage,

and how shocking the fate of those in his pathway, has been graphically

related by Arthur Reid, a native of the township of Argyle, who received

the account from an aunt, who was fully cognizant of all the facts. The

following is a condensed account:

During the latter part of the summer of 1777, a

scouting party of Indians, consisting of eight,

received either a real or supposed injury from some white persons at New

Perth (now Salem), for which they sought revenge. While prowling around

the temporary fort, they were observed and fired upon, and one of their

number killed. In the presence of a prisoner, a white man, [Samuel

Standish, who was present at the time of the murder of Jane McCrea, and

afterwards gave the account to Jared Sparks, who records it in his "Life

of Arnold." See " Library of American

Biography," Vol. III, Chap. VII.] the remaining seven declared

their purpose to sacrifice the first white family that should come in

their way. This party belonged to a large body of Indians which had been

assembled by General Burgoyne, the British commander, then encamped not

far distant in a northerly direction from Crown Point. In order to inspire

the Indians with courage General Burgoyne considered it expedient, in

compliance with their custom, to give them a war—feast, at which they

indulged in the most extravagant manceuvres, gesticulations, and exulting

vociferations, such as lying in ambush, and displaying their rude armored

devices, and dancing, and whooping, and screaming, and brandishing their

tomahawks and scalping knives.

The particular band, above mentioned, was in command of

an Iroquois chief, who, from his bloodthirsty nature, was called Le Loup,

the wolf,—bold, fiercely revengeful, and well adapted to lead a party bent

on committing atrocities. Le Loup and his band left New Perth en route

to the place where the van of Burgoyne’s army was encamped. The family

of Duncan McArthur, consisting of himself, wife and four children, lived

on the direct route. Approaching the clearing upon which the dwelling

stood, the Indians halted in order to make preparations for their fiendish

design. Every precaution was taken, even to enhancing their naturally

ferocious appearance by painting their faces, necks and shoulders with a

thick coat of vermilion. The party next moved forward with stealthy steps

to the very edge of the forest, where again they halted in order to mature

the final plan of attack.

Fortunately for the McArthur family, on that day, two

neighbors had come for the purpose of assisting in the breaking of a

horse, and, when the Indians saw them, and also the three

buildings, which they mistook for residences, they

became disconcerted. They decided as there were three men present, and the

same number of houses, there must also be three families.

The Indians withdrew exasperated, but none the less

determined to seek vengeance. With elastic step, and in single file they

pressed forward, and an hour later came to another clearing, in the midst

of which stood a dwelling, occupied by the family of John Allen,

consisting of five persons, viz., himself and wife and three children.

Temporarily with them at the time were Mrs. Allen’s sister, two negroes

and a negress. John Allen was notoriously in sympathy with the purposes of

the British king. When the Indians steathily crept to the edge of the

clearing they observed the white men busily engaged reaping the wheat

harvest. They decided to wait until the reapers retired for dinner. Their

white prisoner begged to be spared from witnessing the scene about to be

enacted. This request was finally granted, and one of the Indians remained

with him as a guard, while the others went forward to execute their

purpose.

When the family had become seated at the table the

Indians burst upon them with a fearful yell. When the neighbors came they

found the body of John Allen a few rods from the house. Apparently he had

escaped through a back door, but had been overtaken and shot down. Nearer

the house, but in the same direction, were the bodies of Mrs. Allen, her

sister, and the youngest child, all tomahawked and scalped. The other two

children were found hidden in a bed, but also tomahawked and scalped. One

of the negroes was found in the doorway, his body gashed and mutilated in

a horrible manner. From the wounds inflicted on his body it was thought he

had made a desperate resistance. The position of the remaining two has not

been distinctly recollected.

George Kilmore, father of Mrs. Allen and owner of the

negroes, who lived three miles distant, becoming anxious on account of the

prolonged absence of his daughter and servants, on the Sunday following,

sent a negro boy on an errand of inquiry. As the boy approached the house,

the keen-scented horse, which he was riding, stopped and refused to go

farther. After much difficulty he was urged forward until his rider got a

view of the awful scene. The news brought by the boy spread rapidly, and

the terror-stricken families fled to various points for protection, many

of whom went to Fort Edward. After Burgoyne had been hemmed in, the

families cautiously returned to their former homes.

From Friday afternoon, July 25th, until Sunday

morning following, the whereabouts of Le Loup and his band cannot be

determined. But on that morning they made their appearance on the brow of

the hill north of Fort Edward, and then and there a shocking tragedy was

enacted, which thoroughly aroused the people, and formed quite an element

in the overthrow and surrender of Burgoyne’s army. It was the massacre of

Miss Jane McCrea, a lovely, amiable and intelligent lady. This tragedy at

once drew the attention of all America. She fell under the blow of the

savage Le Loup, and the next instant he flung down his gun, seized her

long, luxuriant hair with one hand, with the other passed the scalping

knife around nearly the whole head, and, with a yell of triumph, tore the

beautiful but ghastly trophy from his victim’s head.

It is a work of superogation to say that the Highland

settlers of Argyle were strongly imbued with religious sentiments. That

question has already been fully commented on. The colony early manifested

its disposition to build churches where they might worship. The first of

these houses were humble in their pretensions, but fully in keeping with a

pioneer settlement in the wilderness. Their faith was the same as that

promulgated by the Scotch-Irish in the adjoining neighborhood, and were

visited by the pastor of the older settlement. They do not appear to have

sustained a regular pastor until after the Peace of 1783. |