|

The earliest, largest and most important settlement of

Highlanders in America, prior to the Peace of 1783, was in North Carolina,

along Cape Fear River, about one hundred miles from its mouth, and in what

was then Bladen, but now Cumberland County. The time when the Highlanders

began to occupy this territory is not definitely known; but some were

located there in 1729, at

the time of the separation of the province into North and. South Carolina.

It is not known what motive caused the first set-tiers to select that

region. There was no leading clan in this movement, for various ones were

well represented. At the head-waters of navigation these pioneers

literally pitched their tent in the wilderness, for there were but few

human abodes to offer them shelter. The chief occupants of the soil were

the wild deer, turkeys, wolves, raccoons, opossums, with huge rattlesnakes

to contest the intrusion. Fortunately for the homeless immigrant the

climate was genial, and the stately tree would afford him shelter while he

constructed a house out of logs proffered by the forest. Soon they began

to fell the primeval forest, grub, drain, and clear the rich alluvial

lands bordering on the river, and plant such vegetables as were to give

them subsistence.

In course of time a town was formed,

called Campbellton, then Cross Creek, and after the Revolution, in honor

of the great Frenchman, who was so truly loyal to Washington, it was per

manently changed to Fayetteville.

The immigration to North Carolina

was accelerated, not only by the accounts sent back to the Highlanders of

Scotland by the first settlers, but particularly under the patronage of

Gabriel Johnston, governor of the province from

1734 until his death in 1752.

He was born in Scotland, educated at the

University of St. Andrews, where he became professor of Oriental

languages, and still later a political writer in London. He bears the

reputation of having done more to promote the prosperity of North Carolina

than all its other colonial governors combined. However, he was often

arbitrary and unwise with his power, besides having the usual misfortune

of colonial governors of being at variance with the legislature. He was

very partial to the people of his native country, and sought to better

their condition by inducing them to emigrate to North Carolina. Among the

charges brought against him, in 1748, was his inordinate fondness for

Scotchmen, and even Scotch rebels. So great, it was alleged, was his

partiality for the latter that he showed no joy over the king’s "glorious

victory of Culloden;" and "that he had appointed one William McGregor, who

had been in the Rebellion in the year

1715, a Justice of the Peace

during the late Rebellion (1745) and was not himself without suspicion of

disaffection to His Majesty’s Government." [North

Carolina Colonial Records, Vol. IV, p. 931.]

The "Colonial Records of North

Carolina" contain many distinctively Highland names, most of which refer

to persons whose nativity was in the Scottish Highlands; but these furnish

no certain criterion, for doubtless some of the parties, though of

Highland parents, were born in the older provinces, while in later

colonial history others belong to the Scotch-Irish, who came in that great

wave of migration from Ulster, and found a lodgment upon the headwaters of

the Cape Fear, Pee Dee and Neuse. Many of the early Highland emigrants

were very prominent in the annals of the colony, among whom none were more

so than Colonel James Innes, who was born about the year

1700 at Cannisbay, a town the extreme northern

point of the coast of Scotland. He was a personal friend of Governor

Dinwiddie of Virginia, who in 1754 appointed him commander-in-chief of all

the forces in the expedition to the Ohio,—George Washington being the

colonel commanding the Virginia regiment. He had previously seen some

service as a captain in the unsuccessful expedition against Carthagenia.

The real impetus of the Highland emigration to North

Carolina was the arrival, in 1739, of

a "shipload," under the guidance of Neil McNeill, of Kintyre, Scotland,

who settled also on the Cape Fear, amongst those who had preceded him.

Here he found Hector McNeill, called "Bluff Hector," from his residence

near the bluffs above Cross Creek.

Neil McNeill, with his countrymen, landed on the Cape

Fear during the month of September. They numbered three hundred and fifty

souls, principally from Argyleshire. At the ensuing session of the

legislature they made application for substantial encouragement, that they

might thereby be able to induce the rest of their friends and

acquaintances to settle in the country. While this petition was pending,

in order to encourage them and others and also to show his good will, the

governor appointed, by the council of the province, a certain number of

them justices of the peace, the commissions bearing date of February

28, 1740. The proceedings show that it was

"ordered that a new commission of peace for Bladen directed to the

following persons: Mathew Rowan, Wm Forbes, Hugh Blaning, John Clayton,

Robert Hamilton, Griffeth Jones, James Lyon, Duncan Campbel, Dugold

McNeil, Dan McNeil, Wm. Bartram and Samuel Baker hereby constituting and

appointing them Justices of the Peace for the said county." [Ibid,

p. 447.]

These were the first so appointed.. The petition was

first heard in the upper house of the legislature, at Newbern, and on

January 26, 1740, the following action was

taken:

"Resolved, that the Persons mentioned in said Petition,

shall be free from payment of any Publick or County tax for Ten

years next ensuing their Arrival.

"Resolved, that towards their subsistence the sum of

one thousand pounds be paid out of the Publick money, by His Excellency’s

warrant to be lodged with Duncan Campbell, Dugald McNeal, Daniel McNeal,

Coll. McAlister and Neal McNeal Esqrs., to be by them distributed among

the several families in the said Petition mentioned.

"Resolved, that as an encouragement for Protestants to

remove from Europe into this Province, to settle themselves in bodys or

Townships, That all such as shall so remove into this

province, provided they exceed forty persons in one body or Company, they

shall be exempted from payment of any Publick or County tax for the space

of Ten years, next ensuing their Arrival.

"Resolved, that an address be presented to his

Excellency the Governor to desire him to use his Interest, in such manner,

as he shall think most proper to obtain an Instruction for giveing encouragement

to Protestants from foreign parts, to settle in Townships within this

Province, to be set apart for that purpose after the manner, and with such

priviledges and advantages, as is practised in South Carolina." [p.

490. Ibid, p.533.]

The petition was concurred in by the lower house on

February 21st, and on the 26th, after reciting the

action of the upper house in relation to the petition, passed the

following:

"Resolved, That this House concurs with the several

Resolves of the Upper House in the abovesd Message Except that relateing

to the thousand pounds which this House refers till next Session of

Assembly for Consideration."

At a meeting of the council held at Wilmington, June 4,

1740, there were presented petitions for patents of

lands, by the following persons, giving acres and location, as granted:

Name. Acres. County.

Thos Clarks 320 N. Hanover

James McLachlan 160 Bladen H

ector McNeil 300

Duncan Campbell 150

James McAlister 640

James McDugald 640

Duncan Campbell 75

Hugh McCraine 500

Duncan Campbell 320

Gilbert Pattison 640

Rich Lovett 855

Tyrrel

Rd Earl 108 N. Hanover

Jno McFerson 320 Bladen

Duncan Campbell 300

Neil McNeil 150

Duncan Campbell 140

Jno Clark 320

Malcolm McNeil 320

Neil McNeil 400

Arch Bug 320

Duncan Campbel 640 Bladen

Jas McLachlen 320

Murdock McBraine 320

Jas Campbel 640

Patric Stewart 320

Arch Campley 320

Dan McNeil 105 (400) 400

Neil McNeil 400

Duncan Campbel 320

Jno Martileer 160

Daniel McNeil 320

Wm Stevens 300

Dan McNeil 400

Jas McLachlen 320

Wm Speir i6o Edgecombe

Jno Clayton 100 Bladen

Sam Portevint 640 N. Hanover

Charles Harrison 320

Robt Walker 640

Jas Smalwood 640

Wm Faris 400 640 640

Richd Canton 180 Craven

Duncan Campbel 150 Bladen

Neil McNeil 321

Alex McKey 320

Henry Skibley 320

Jno Owen 200

Duncan Campbel 400

Dougal Stewart 640

Arch Douglass 200 N. Hanover

James Murray 320

Robt Clark 200

Duncan Campbel 148 Bladen

James McLachlen 320

Arch McGill 500

Jno Speir 100 Edgecombe

James Fergus 640

Rufus Marsden 640

Hugh Blaning 320 (surplus land) Bladen

Robt Hardy 400 Beaufort

Wm Jones 354 350

All the above names, by no means are Highland; but as

they occur in the same list, in all probability, came on the same ship,

and were probably connected by kindred ties with the Gaels.

The colony was destined soon to receive a great influx

from the Highlands of Scotland, due to the frightful oppression and

persecution which immediately followed the battle of Culloden. Not

satisfied with the merciless harrying of the Highlands, the English army

on its return into England carried with it a large number of prisoners,

and after a hasty military trial many were publicly executed. Twenty-two

suffered death in Yorkshire; seventeen were put to death in Cumberland;

and seventeen at Kennington Common, near London. When the king’s vengeance

had been fully glutted, he pardoned a large number, on condition of their

leaving the British Isles and emigrating to the plantations, after having

first taken the oath of allegiance.

The collapsing of the romantic scheme to re-establish

the Stuart dynasty, in which so many brave and generous mountaineers were

enlisted, also brought an indiscriminate national punishment upon the

Scottish Gaels, for a blow was struck not only at those "who were out"

with prince Charles, but also those who fought for the reigning dynasty.

Left without chief, or protector, clanship broken up, homes destroyed and

kindred murdered, dispirited, outlawed, insulted and without hope of

palliation or redress, the only ray of light pointed across the Atlantic

where peace and rest were to be found in the unbroken forests of North

Carolina. Hence, during the years 1746 and 1747,

great numbers of Highlanders, with their families and the families of

their friends, removed to North Carolina and settled along the Cape Fear

river, covering a great space of country, of which Cross Creek, or

Campbelton, now Fayetteville, was the common center. This region received

shipload after shipload of the harassed, down-trodden and maligned people.

The emigration, forced by royal persecution and authority, was carried on

by those who desired to improve their condition, by owning the land they

tilled. In a few years large companies of Highlanders joined their

countrymen in Bladen County, which has since been subdivided into the

Counties of Anson, Bladen, Cumberland, Moore, Richmond,

Robeson and Sampson, but the greater portion

established themselves within the present limits of Cumberland, with

Fayetteville the seat of justice. There was in fact a Carolina mania which

was not broken until the beginning of the Revolution. [See

Appendix, Note C.] The flame of enthusiasm passed like wildfire

through the Highland glens and Western Isles. It pervaded all classes,

from the poorest crofter to the well-to-do farmer, and even men of easy

competence, who were according to the appropriate song of the day,

"Dol a dh’iarruidh an fhortain do North Carolina."

Large ocean crafts, from several of the Western Lochs,

laden with hundreds of passengers sailed direct for the far west. In that

day this was a great undertaking, fraught with perils of the sea, and a

long, comfortless voyage. Yet all this was preferable than the homes they

loved so well; but no longer homes to them! They carried with them their

language, their religion, their manners, their customs and costumes. In

short, it was a Highland community transplanted to more hospitable shores.

The numbers of Highlanders at any given period can only

relatively be known. In 1753 it was estimated that in Cumber- land County

there were one thousand Highlanders capable of bearing arms, which would

make the whole number between four and five thousand,—to say nothing of

those in the adjoining districts, besides those scattered in the other

counties of the province.

The people at once settled quietly and devoted their

energies to improving their lands. The country rapidly developed and

wealth began to drop into the lap of the industrious. The social claims

were not forgotten, and the political demands were attended to. It is

recorded that in 1758 Hector McNeil was sheriff of Cumberland

County, and as his salary was but £10, it indicates his services were not

in demand, and there was a healthy condition of affairs.

Hector McNeil and Alexander McCollister represented

Cumberland County in the legislature that assembled at Wilmington April

13, 1762. In 1764 the members were Farquhar

Campbell and Walter Gibson,—the former being also a member in 1769, 1770,

and 1775, and during this period one of the leading men not only of the

county, but also of the legislature. Had he, during the Revolution, taken

a consistent position in harmony with his former acts, he would have been

one of the foremost patriots of his adopted state; but owing to his

vacillating character, his course of conduct inured to his discomfiture

and reputation.

The legislative body was clothed with sufficient powers

to ameliorate individual distress, and was frequently appealed to for

relief. In quite a list of names, seeking relief from "Public duties and

Taxes," April 16, 1762, is that of Hugh McClean, of Cumberland

county. The relief was granted. This would indicate that there was more or

less of a struggle in attaining an independent home, which the legislative

body desired to assist in as much as possible, in justice to the

commonwealth.

The Peace of 1763 not only saw the American Colonies

prosperous, but they so continued, making great strides in development and

growth. England began to look towards them as a source for additional

revenue towards filling her depleted exchequer; and, in order to realize

this, in March, 1765, her parliament passed, by great majorities,

the celebrated act for imposing stamp duties in America. All America was

soon in a foment. The people of North Carolina had always asserted their

liberties on the subject of taxation. As early as 1716, when the province,

all told, contained only eight thousand inhabitants, they entered upon the

journal of their assembly the formal declaration "that the impressing of

the inhabitants or their property under pretence of its being for the

public service without authority of the Assembly, was unwarrantable and a

great infringement upon the liberty of the subject." In 1760 the Assembly

declared its indubitable right to frame and model every bill whereby an

aid was granted to the king. In 1764 it entered upon its journal a

peremptory order that the treasurer should not pay out any money by order

of the governor and council without the concurrence of the assembly.

William Tryon assumed the duties of governor March 28,

1765, and immediately after he took charge of affairs the assembly was

called, but within two weeks he prorogued it; said to have been done in

consequence of an interview with the speaker of the assembly, Mr. Ashe,

who, in answer to a question by the governor on the Stamp Act, replied,

"We will fight it to the death." The North Carolina records show it was

fought even to "the death."

The prevalent excitement seized the Highlanders along

the Cape Fear. A letter appeared in "The North Carolina Gazette," dated at

Cross Creek, January 30, 1766, in which the writer urges the people by

every consideration, in the name of "dear Liberty" to rise in their might

and put a stop to the seizures then in pro- gress. He asks the people if

they have "lost their senses and their souls, and are they determined

tamely to submit to slavery." Nor did the matter end here, for, the people

of Cross Creek gave vent to their resentment by burning lord Bute in

effigy.

Just how far statistics represent the wealth of a

people may not be wholly determined At this period of the history,

referring to a return of the counties, in 1767, it is stated that Anson

county, called also parish of St George, had six hundred and ninety-six

white taxables, that the people were in general poor and unable to support

a minister Bladen county, or St Martin’s parish, had seven hundred and

ninety-one taxable whites, and the inhabitants in middling circumstances.

Cumberland, or St David’s parish, had eight hundred and ninety-nine

taxable whites, "mostly Scotch—Support a Presbyterian Minister."

The Colonial Records of North Carolina do not exhibit a

list of the emigrants, and seldom refer to the ship by name. Occasionally,

however, a list has been preserved in the minutes of the official

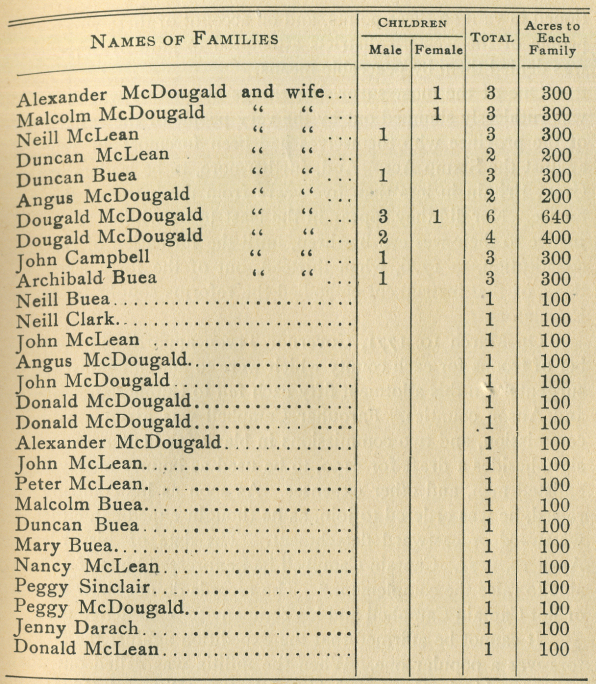

proceedings. Hence it may be read that on November 4,

1767, there landed at Brunswick, from the Isle of Jura, Argyle-shire,

Scotland, the following names of families and persons, to whom were

allotted vacant lands, clear of all fees, to be taken up in Cumberland or

Mecklenburgh counties, at their option:

These names show they were from Argyleshire, and

probably from the Isle of Mull, and the immediate vicinity of the present

city of Oban.

The year 1771 witnessed civil strife in North Carolina.

The War of the Regulators was caused by oppression in disproportionate

taxation; no method for payment of taxes in produce, as in other counties;

unfairness in transactions of business by officials; the privilege

exercised by lawyers to commence suits in any court they pleased, and

unlawful fees extorted. The assembly was peti

tioned in vain on these points, and on account of these

wrongs the people of the western districts attempted to gain by force what

was denied them by peaceable means.

One of the most surprising things about this war is

that it was ruthlessly stamped out by the very people of the eastern part

of the province who themselves had been foremost in rebellion against the

Stamp Act. And, furthermore, to be leaders against Great Britain in less

than five years from the battle of the Alamance. Nor did they appear in

the least to be willing to concede justice to their western brethren,

until the formation of the state constitution, in 1776, when thirteen, out

of the forty-seven sections, of that instrument embodied the reforms

sought for by the Regulators.

On March 10, 1771, Governor Tryon apportioned the

number of troops for each county which were to march against the

insurgents In this allotment fifty each fell to Cumberland, Bladen,

and Anson counties. Farquhar Campbell was given a

captain’s commission, and two commissions in blank for lieutenant and

ensign, besides a draft for £150, to be used as bounty money to the

enlisted men, and other expenses. As soon as his company was raised, he

was ordered to join, as he thought expedient, either the westward or

eastward detachment. The date of his orders is April 18, 1771. Captain

Campbell had expressed himself as being able to raise the complement. The

records do not show whether or not Captain Campbell and his company took

an active part.

It cannot be affirmed that the expedition against the

Regulators was a popular one. When the militia was called out, there arose

trouble in Craven, Dobbs, Johnston, Pitt and Edgecombe counties, with no

troops from the Albemarle section. In Bute county where there was a

regiment eight hundred strong, when called upon for fifty volunteers, all

broke rank, without orders, declaring that they were in sympathy with the

Regulators.

The freeholders living near Campbelton on March 13,

1772, petitioned Governor Martin for a change in the charter of their

town, alleging that as Campbelton was a trading town persons

temporarily residing there voted, and thus the power of election was

thrown into their hands, because the property owners were fewer in

numbers. They desired "a new Charter impowering all persons, being

Freeholders within two miles of the Courthouse of Campbelton or seized of

an Estate for their own, or the life of any other person in any

dwelling-house (such house having a stone or brick Chimney thereunto

belonging and appendent) to elect a Member to represent them in General

Assembly. Whereby we humbly conceive that the right of election will be

lodged with those who only have right to Claim it and the purposes for

which the Charter was granted to encourage Merchants of property to settle

there fully answered."

Among the names signed to this petition are those of

Neill MacArther, Alexr. MacArther, James McDonald, Benja. McNatt, Ferqd.

Campbell, and A. Macline. The charter was granted.

The people of Cumberland county had a care for their

own interests, and fully appreciated the value of public buildings. Partly

by their efforts, the upper legislative house, on February 24,

1773, passed a bill for laying out a public road from the Dan through the

counties of Guilford, Chatham and Cumberland to Campbelton. On the 26th

same month, the same house passed a bill for regulating the borough of

Campbelton, and erecting public buildings therein, consisting of court

house, gaol, pillory and stocks, naming the following persons to be

commissioners: Alexander McAlister, Farquhard Campbell, Richard Lyon,

Robert Nelson, and Robert Cochran. The same year Cumberland county paid in

quit-rents, fines and forfeitures the sum of £206.

In September, 1773, a boy named Reynold McDugal

was condemned for murder. His youthful appearance, looking to be but

thirteen, though really eighteen years of age, enlisted the sympathy of a

great many, who petitioned for clemency, which was granted. To this

petition were attached such Highland names as, Angus Camel, Alexr.

McKlarty, James McKlarty, Malcolm McBride, Neil McCoulskey, Donald

McKeithen, Duncan McKeithen, Gilbert McKeithen, Archibald McKeithen,

Daniel Mc-Farther, John McFarther, Daniel Graham, Malcolm Graham, Malcolm

McFarland, Murdock Graham, Michael Graham, John McKown, Robert McKown,

William McKown, Daniel Campbell, John Campbell, Iver McKay, John McLeod,

Alexr. Graham, Evin McMullan, John McDuffie, William McNeil, Andw.

McCleland, John McCleland, Wm. McRei, Archd. McCoulsky, James McCoulsky,

Chas. McNaughton, Jno. McLason.

The Highland clans were fairly represented, with a

preponderance in favor of the McNeils. They still wore their distinctive

costume, the plaid, the kilt, and the sporan,—and mingled together, as

though they constituted but one family. A change now began to take place

and rapidly took on mammoth proportions. The MacDonalds of Raasay and Skye

became impatient under coersion and set out in great numbers for North

Carolina. Among them was. Allan MacDonald of Kingsborough, and his famous

wife, the heroine Flora, who arrived in 1774. Allan MacDonald succeeded to

the estate of Kingsburgh in 1772, on the death of his father, but

finding it incumbered with debt, and embarrassed in his affairs, he

resolved in 1773 to go to North Carolina, and there hoped to mend his

fortunes. He settled in Anson county. Although somewhat aged, he had the

graceful mein and manly looks of a gallant Highlander. He had jet black

hair tied behind, and was a large, stately man, with a steady, sensible

countenance. He wore his tartan thrown about him, a large blue bonnet with

a knot of black ribbon like a cockade, a brown short coat, a tartan

waist-coat with gold buttons and gold button holes, a bluish philabeg, and

tartan hose. At once he took precedence among his countrymen, becoming

their leader and adviser The Macdonalds, by 1775, were so numerous in

Cumberland county as to be called the "Clan Donald," and the insurrection

of February, 1776, is still known as the "Insurrection of the Clan

MacDonald."

Little did the late comers know or realize the

gathering storm. The people of the West Highlands, so remote from the

outside world,, could not apprehend the spirit of liberty that was being

awakened in the Thirteen Colonies. Or, if they heard of it, the report

found no special lodgement. In short, there were but few capable of

realizing what the outcome would be. Up to the very breaking out of

hostilities the clans poured forth emigrants into North Carolina.

Matters long brewing now began to culminate and evil

days grew apace. The ruling powers of England refused to understand the

rights of America, and their king rushed headlong into war. The colonists

had suffered long and patiently, but when the overt act came they appealed

to arms. Long they bore misrule. An English king, of his own whim, or the

favoritism of a minister, or the caprice of a woman good or bad, or for

money in hand paid, selected the governor, chief justice, secretary,

receiver-general, and attorney-general for the province. The governor

selected the members of the council, the associate judges, the

magistrates, and the sheriffs. The clerks of the county courts and the

register of deeds were selected by the clerk of pleas, who having bought

his office in England came to North Carolina and peddled out "county

rights" at prices ranging from £4 to £40 annual rent per county.

Scandalous abuses accumulated, especially under such governors as were

usually chosen. The people were still loyal to England, even after the

first clash of arms, but the open rupture rapidly prepared them for

independence. The open revolt needed only the match. When that was

applied, a continent was soon ablaze, controlled by a lofty patriotism.

The steps taken by the leaders of public sentiment in

America were prudent and statesmanlike. Continental and Provincial

Congresses were created. The first in North Carolina convened at Newbern,

August 25, 1774. Cumberland county was represented by Farquhard

Campbell and Thomas Rutherford. The Second Congress convened at the same

place April 30, 1775. Again the same parties represented Cumberland

county, with an additional one for Campbelton in the person of Robert

Rowan. At this time the Highlanders were in sympathy with the people of

their adopted country. But not all, for on July 3rd, Allan MacDonald of

Kingsborough went to Fort Johnson, and concerted with Governor Martin the

raising of a battalion of "the good and faithful Highlanders." He fully

calculated on the recently settled MacDonalds and MacLeods. All who took

part in the Second Congress were not prepared to take or realize the logic

of their position, and what would be the final result.

The Highlanders soon became an object of consideration

to the leaders on both sides of the controversy. They were numerically

strong, increasing in numbers, and their military qualities beyond

question. Active efforts were put forth in order to induce them to throw

the weight of their decision both to the patriot cause and also to that of

the king. Consequently emissaries were sent amongst them. The prevalent

impression was that they had a strong inclination towards the royalist

cause, and that party took every precaution to cement their loyalty. Even

the religious side of their natures was wrought upon.

The Americans early saw the advantage of decisive

steps. In a letter from Joseph Hewes, John Penn, and William Hooper, the

North Carolina delegates to the Continental Congress, to the members of

the Provincial Congress, under date of December 1, 1775, occurs the

admission that "in our attention to military preparations we have not lost

sight of a means of safety to be effected by the power of the pulpit,

reasoning and persuasion. We know the respect which the Regulators and

Highlanders entertain for the clergy, they still feel the impressions of a

religious education, and truths to them come with irresistible influence

from the mouths of their spiritual pastors. * * * The Continental Congress

have thought proper to direct us to employ two pious clergymen to make a

tour through North Carolina in order to remove the prejudices which the

minds of the Regulators and Highlanders may labor under with respect to

the justice of the American controversy, and to obviate the religious

scruples which Governor Tryon’s heart-rending oath has implanted in their

tender consciences We are employed at present in quest of some persons who

may be equal to this undertaking "

The Regulators were divided in their sympathies, and it

was impossible to find a Gaelic-speaking minister, clothed with authority,

to go among the Highlanders. Even if such a personage could have been

found, the effort would have been counteracted by the influence of John

McLeod, their own minister. His sympathies, though not boldly expressed,

were against the interests of the Thirteen Colonies, and on account of his

suspicious actions was placed under arrest, but discharged May 11, 1776,

by the Provincial Congress, in the following order:

"That the Rev. John McLeod, who was brought to this

Congress on suspicion of his having acted inimical to the rights of

America, be discharged from his further attendance."

August 23, 1775, the Provincial Congress

appointed, from among its members, Archibald Maclaine, Alexander

McAlister, Farquhard Campbell, Robert Rowan, Thomas Wade, Alexander McKay,

John Ashe, Samuel Spencer, Walter Gibson, William Kennon, and James

Hepburn, "a committee to confer with the Gentlemen who have lately arrived

from the Highlands in Scotland to settle in this Province, and to explain

to them the Nature of our Unhappy Controversy with Great Britain, and to

advise and urge them to unite with the other Inhabitants of America in

defence of those rights which they derive from God and the Constitution."

No steps appear to have been taken by the Americans to

organize the Highianders into military companies, but rather their efforts

were to enlist their sympathies. On the other hand, the royal governor,

Josiah Martin, took steps towards enrolling them into active British

service. In a letter to the earl of Dartmouth, under date of June 30,

1775, Martin declares he "could collect immediately among the emigrants

from the Highlands of Scotland, who were settled here, and immoveably

attached to His Majesty and His Government, that I am assured by the best

authority I may compute at 3000 effective men," and begs permission "to

raise a Battalion of a Thousand Highlanders here," and "I would most

humbly beg leave to recommend Mr. Allen McDonald of Kingsborough to be

Major, and Captain Alexd. McLeod of the Marines now on half pay to be

first Captain, who be-sides being men of great worth, and good character,

have most extensive influence over the Highlanders here, great part of

which are of their own names and familys, and I should flatter myself that

His Majesty would be graciously pleased to permit me to nominate some of

the Subalterns of such a Battalion, not for pecuniary consideration, but

for encouragement to some active and deserving young Highland Gentlemen

who might be usefully employed in the speedy raising the proposed

Battalion. Indeed I cannot help observing My Lord, that there are three of

four Gentlemen of consideration here, of the name of McDonald, and a

Lieutenant Alexd. McLean late of the Regiment now on

half pay whom I should be happy to see appointed Captains in such a

Battalion, being persuaded they would heartily promote and do credit to

His Majesty’s Service."

November 12, 1775, the governor farther reports to the

same that he can assure "your Lordship that the Scotch Highlanders here

are generally and almost without exception staunch to Government," and

that "Captain Alexr. McLeod, a Gentleman from the Highlands of Scotland

and late an Officer in the Marines who has been settled in this Province

about a year and is one of the Gentlemen I had the honor to recommend to

your Lordship to be appointed a Captain in the Battalion of Highlanders, I

proposed with his Majesty’s permission to raise here found his way down to

me at this place about three weeks ago and I learn from him that he is as

well as his father in law, Mr. Allan McDonald, proposed by me for Major of

the intended Corps moved by my encouragements have each raised a company

of Highlanders since which a Major McDonald who came here some time ago

from Boston under the orders from General Gage to raise Highlanders to

form a Battalion to be commanded by Lieut Coll. Allan McLean has made them

proposals of being appointed Captains in that corps, which they have

accepted on the Condition that his Majesty does not approve my proposal of

raising a Batallion of Highlanders and reserving to themselves the choice

of appointments therein in case it shall meet with his Majesty’s

approbation in support of that measure. I shall now only presume to add

that the taking away those Gentlemen from this Province will in a great

measure if not totally dissolve the union of the Highlanders in it now

held together by their influence, that those people in their absence may

fall under the guidance of some person not attached like them to

Government in this Colony at present but it will ever be maintained by

such a regular military force as this established in it that will

constantly reunite itself with the utmost facility and consequently may be

always maintained upon the most respectable footing."

The year 1775 witnessed the North Carolina patriots

very alert. There were committees of safety in the various counties; and

the Provincial Congress began its session at Hillsborough August 21st.

Cumberland County was represented by Farquhard Campbell, Thomas

Rutherford, Alexander McKay, Alexander McAlister and David Smith,

Campbelton sent Joseph Hepburn. Among the members of this Congress having

distinctly Highland names, the majority of whom doubtless were born in the

Highlands, if not all, besides those already mentioned, were John Campbell

and John Johnston from Bertie, Samuel Johnston of Chowan, Duncan Lamon of

Edgecombe, John McNitt Alexander of Mecklenburg, Kenneth McKinzie of

Martin, Jeremiah Frazier or Tyrell, William Graham of Tryon, and Archibald

Maclaine of Wilmington. One of the acts of this Congress was to divide the

state into military districts, and the appointment of field officers of

the Minute Men. For Cumberland county Thomas Rutherford was appointed

colonel; Alexander McAlister, lieutenant colonel; Duncan McNeill, first

major; Alexander McDonald, second major. One company of Minute Men was to

be raised. This Act was passed on September 9th.

As the name of Farquhard Campbell often occurs in

connection with the early stages of the Revolution, and quite frequently

in the Colonial Records from 1771 to 1776, a brief notice of him may be of

some interest. He was a gentleman of wealth, education and influence, and,

at first, appeared to be warmly attached to the cause of liberty. As has

been noticed he was a member of the Provincial Congress, and evinced much

zeal in promoting the popular movement, and, as a visiting member from

Cumberland county attended the meeting of the Safety Committee at

Wilmington, on July 20, 1776. When Governor Martin abandoned

his palace and retreated to Fort Johnston, and thence to an armed ship, it

was ascertained that he visited Campbell at his residence. Not long

afterwards the governor’s secretary asked the Provincial Congress "to give

Sanction and Safe Conduct to the removal of the most valuable Effects of

Governor Martin on Board the Man of War and his Coach and Horses to Mr.

Farquard Campbell’s." When the request was submitted to that body, Mr.

Campbell "expressed a sincere desire that the Coach and Horses should not

be sent to his House in Cumberland and is amazed that such a proposal

should have been made without his approbation or privity."

On account of his positive disclaimer the Congress, by

resolution exonerated him from any improper conduct, and that he had

"conducted himself as an honest member of Society and a friend to the

American Cause."

He dealt treacherously with the governor as well as

with Congress. The former, in a letter to the earl of Dartmouth, October

16, 1775, says:

"I have heard too My Lord with infinitely greater

surprise and concern that the Scotch Highlanders on whom I had such firm

reliance have declared themselves for neutrality, which I am informed is

to be attributed to the influence of a certain Mr. Farquhard Campbell an

ignorant man who has been settled from childhood in this Country, is an

old Member of the Assembly and has imbibed all the American popular

principles and prejudices. By the advice of some of his Countrymen I was

induced after the receipt of your Lordship’s letter No. 16 to communicate

with this man on the alarming state of the Country and to sound his

disposition in case of matters coming to extremity here, and he expressed

to me such abhorence of the violences that had been done at Fort Johnston

and in other instances and discovered so much jealousy and apprehension of

the ill designs of the Leaders in Sedition here, giving me at the same

time so strong assurances of his own loyalty and the good dispositions of

his Countrymen that I unsuspecting his dissimulation and treachery was led

to impart to him the encouragements I was authorized to hold out to his

Majesty’s loyal Subjects in this Colony who should stand forth in support

of Government which he received with much seeming approbation and

repeatedly assured me he would consult with the principles among his

Countrymen without whose concurrence he could promise nothing of himself,

and would acquaint me with their determinations. From the time of this

conversation between us in July I heard nothing of Mr. Campbell until

since the late Convention at Hillsborough, where he appeared in the

character of a delegate from the County of Cumberland and there, according

to my information, unasked and unsolicited and without provocation of any

sort was guilty of the base Treachery of promulgating all I had said to

him in confidential secrecy, which he had promised sacredly and inviolably

to observe, and of the aggravating crime of falsehood in making additions

of his own invention and declaring that he had rejected all my

propositions."

The governor again refers to him in his letter to the

same,. dated November 12, 1775:

"From Capt. McLeod, who seems to be a man of

observation and intelligence, I gather that the inconsistency of Farquhard

Campbell’s conduct * * * has proceeded as much

from jealousy of the Superior consequence of this Gentleman and his father

in law with the Highlanders here as from any other motive. This schism is

to be lamented from whatsoever cause arising, but I have no doubt that I

shall be able to reconcile the interests of the parties whenever I have

power to act and can meet them together."

Finally he threw off the mask, or else had changed his

views, and openly espoused the cause of his country’s enemies. He was

seized at his own house, while entertaining a party of royalists, and

thrown into Halifax gaol: A committee of the Provincial Congress, on April

20, 1776, reported "that Farquhard Campbell disregarding the sacred

Obligations he had voluntarily entered into to support the Liberty of

America against all usurpations has Traitorously and insiduously

endeavored to excite the Inhabitants of this Colony to take arms and levy

war in order to assist the avowed enemies thereof. That when a prisoner on

his parole of honor he gave intelligence of the force and intention of the

American Army under Col. Caswell to the Enemy and advised them in what

manner they might elude them."

He was sent, with other prisoners, to Baltimore, and

thence, on parole, to Fredericktown, where he behaved "with much

resentment and haughtiness." On March 3, 1777, he appealed to Governor

Caswell to be permitted to return home, offering to mortgage his estate

for his good behavior. Several years after the Revolution he was a member

of the Senate of North Carolina.

The stormy days of discussion, excitement, and

extensive Preparations for war, in 1775, did not deter the Highlanders in

Scotland from seeking a home in America. On October 21st, a body of one

hundred and seventy-two Highlanders, including men, women and children

arrived in the Cape Fear river, on board the George, and made application

for lands near those already located by their relatives. The governor took

his usual precautions with them for in a letter to the earl of Dartmouth,

dated November 12th, he says:

"On the most solemn assurances of their firm and

unalterable loyalty and attachment to the King, and their readiness to lay

down their lives in the support and defence of his Majesty’s Government, I

was induced to Grant their request on the Terms of their taking such lands

in the proportions allowed by his Majesty’s Royal Instructions, and

subject to all the conditions prescribed by them whenever grants may be

passed in due form, thinking it were advisable to attach these people to

Government by granting as matter of favor and courtesy to them what I had

not power to prevent than to leave them to possess themselves by violence

of the King’s lands, without owing or acknowledging any obligation for

them, as it was only the means of securing these People against the

seditions of the Rebels, but gaining so much strength to Government that

is equally important at this time, without making any concessions

injurious to the rights and interests of the Crown, or that it has

effectual power to withhold."

In the same letter is the further information that "a

ship is this moment arrived from Scotland with upwards of one hundred and

thirty Emigrants Men, Women and Children to whom I shall think it proper

(after administering the Oath of Allegiance to the Men) to give permission

to settle on the vacant lands of the Crown here on the same principles and

conditions that I granted that indulgence to the Emigrants lately imported

in the ship George."

Many of the emigrants appear to have been seized with

the idea that all that was necessary was to land in America, and the

avenues of affluence would be opened to them Hence there were those who

landed in a distressed condition. Such was the state of the last party

that arrived before the Peace of 1783. There was "a Petition from sundry

distressed Highianders, lately arrived from Scotland, praying that they

might be permitted to go to Cape Fear, in North Carolina, the place where

they intended to settle," laid before the Virginia convention then being

held at Williamsburgh, December 14, 1775. On the same day the convention

gave orders to Colonel Woodford to "take the distressed High-landers, with

their families, under his protection, permit them to pass by land

unmolested to Carolina, and supply them with such provisions as they may

be in immediate want of."

The early days of 1776 saw the culmination of the

intrigues with the Scotch-Highlanders. The Americans realized that the war

party was in the ascendant, and consequently every movement was carefully

watched. That the Americans felt bitterly towards them came from the fact

that they were not only precipitating themselves into a quarrel of which

they were not interested parties, but also exhibited ingratitude to their

benefactors. Many of them came to the country not only poor and needy, but

in actual distress. They were helped with an open hand, and cared for with

kindness and brotherly aid. Then they had not been long in the land, and

the trouble so far had been to seek redress. Hence the Americans felt

keenly the position taken by the Highlanders. On the other hand the

Highlanders had viewed the matter from a different standpoint. They did

not realize the craftiness of Governor Martin in compelling them to take

the oath of allegiance, and they felt bound by what they considered was a

voluntary act, and binding with all the sacredness of religion. They had

ever been taught to keep their promises, and a liar was a greater criminal

than a thief. Still they had every opportunity afforded them to learn the

true status of affairs; independence had not yet been proclaimed;

Washington was still beseiging Boston, and the Americans continued to

petition the British throne for a redress of grievances.

That the action of the Highlanders was ill-advised, at

that time, admits of no discussion. They failed to realize the condition

of the country and the insuperable difficulties to overcome before making

a junction with Sir Henry Clinton. What they

expected to gain by their conduct is uncertain,

and why they should march away a distance of one hundred miles, and then

be transported by ships to a place they knew not where, thus leaving their

wives and children to the mercies of those, whom they had offended and

driven to arms, made bitter enemies of, must ever remain unfathomable. It

shows they were blinded and exhibited the want of even ordinary foresight.

It also exhibited the reckless indifference of the responsible parties to

the welfare of those they so successfully duped. It is no wonder that

although nearly a century and a quarter have elapsed since the Highlanders

unsheathed the claymore in the pine forests of North Carolina, not

a single person has shown the hardihood to applaud

their action. On the other hand, although treated with the utmost charity,

their bravery applauded, they have been condemned for their rude

precipitancy, besides failing to see the changed condition of affairs, and

resenting the injuries they had received from the House of Hanover that

had harried their country and hanged their relatives on the murderous

gallows-tree. Their course, however, in the end proved advantageous to

them; for, after their disastrous defeat, they took an oath to remain

peaceable, which the majority kept, and thus prevented them from being

harrassed by the Americans, and, as loyal subjects of king George, the

English army must respect their rights.

Agents were busily at work among the people preparing

them for war. The most important of all was Allan MacDonald of

Kingsborough. Early he came under the suspicion of the Committee of Safety

at Wilmington. On the very day, July 3, 1775, he was in consultation with

Governor Martin, its chairman was directed to write to him "to know from

himself respecting the reports that circulate of his having an intention

to raise Troops to support the arbitrary measures of the ministry against

the Americans in this Colony, and whether he had not made an offer of his

services to Governor Martin for that purpose."

The influence of Kingsborough was supplemented by that

of Major Donald MacDonald, who was sent direct from the army in Boston. He

was then in his sixty-fifth year, had an extended experience in the army

He was in the Rising of 1745, and headed many of his own name. He now

found many of these former companions who readily listened to his

persuasions All the emissaries sent represented they were only visiting

their friends and relatives. They were all British officers, in the active

service.

Partially in confirmation of the above may be cited a

letter from Samuel Johnston of Edenton, dated July 21, 1775, written to

the Committee at Wilmington:

"A vessel from New York to this place brought over two

officers who left at the Bar to go to New Bern, they are both High-landers,

one named McDonnel the other McCloud. They pretend they are on a visit to

some of their countrymen on your river, but

I think there is reason to suspect their errand of a

base nature. The Committee of this town have wrote to New Bern to have

them secured. Should they escape there I hope you will keep a good lookout

for them."

The vigorous campaign for 1776, in the Carolinas was

determined upon in the fall of 1775, in deference to the oft repeated and

urgent solicitations of the royal governors, and on account of the appeals

made by Martin, the brunt of it fell upon North Carolina. He assured the

home government that large numbers of the Highlanders and Regulators were

ready to take up arms for the king.

The program, as arranged, was for Sir Henry Clinton,

with a fleet of ships and seven corps of Irish Regulars, to be at the

mouth of the Cape Fear early in the year 1776, and there form a junction

with the Highlanders and other disaffected persons from the interior.

Believing that Sir Henry Clinton’s armament would arrive in January or

early in February Martin made preparations for the revolt; for his

"unwearied, persevering agent," Alexander MacLean brought written

assurances from the principal persons to whom he had been directed, that

between two and three thousand men would take the field at the governor’s

summons. Under this encouragement MacLean was sent again into the back

country, with a commission dated January 10, 1776, authorizing Allan

McDonald, Donald McDonald, Alexander McLeod, Donald McLeod, Alexander

McLean, Allen Stewart, William Campbell, Alexander McDonald and Neal

McArthur, of Cumberland and Anson counties, and seventeen other persons

who resided in a belt of counties in middle Carolina, to raise and array

all the king’s loyal subjects, and to march them in a body to Brunswick by

February I5th.

Donald MacDonald was placed in command of this array

and of all other forces in North Carolina with the rank of brigadier

general, with Donald MacLeod next in rank. Upon receiving his orders,

General MacDonald issued the following:

"By His Excellency Brigadier-General Donald McDonald,

Commander of His Majesty’s Forces for the time being, in North Carolina:

A MANIFESTO.

Whereas, I have received information that many of His

Majesty’s faithful subjects have been so far overcome by apprehension of

danger, as to fly before His Majesty’s Army as from the most inveterate

enemy; to remove which, as far as lies in my power, I have thought it

proper to publish this Manifesto, declaring that I shall take the proper

steps to prevent any injury being done, either to the person or properties

of His Majesty’s subjects; and I do further declare it to be my determined

resolution, that no violence shall be used to women and children, as

viewing such outrages to be inconsistent with humanity, and as tending, in

their consequences, to sully the arms of Britons and of Soldiers.

I, therefore, in His Majesty’s name, generally invite

every well-wisher to that form of Government under which they have so

happily lived, and which, if justly considered, ought to be esteemed the

best birth-right of Britons and Americans, to repair to His Majesty’s

Royal Standard, erected at Cross Creek, where they will meet with every

possible civilty, and be ranked in the list of friends and

fellow-Soldiers, engaged in the best and most glorious of all causes,

supporting the rights and Constitution of their country. Those, therefore,

who have been under the unhappy necessity of submitting to the mandates of

Congress and Committees—those lawless, usurped, and arbitrary

tribunals—will have an opportunity, (by joining the King’s Army) to

restore peace and tranquility to this distracted land—to open again the

glorious streams of commerce—to partake of the blessings of inseparable

from a regular administration of justice, and be again,. reinstated in the

favorable opinion of their Sovereign.

Donald McDonald.

By His Excellency’s command:

Kenn. McDonald, P. S."

On February 5th General MacDonald issued another

manifesto in which he declares it to be his "intention that no violation

whatever shall be offered to women, children, or private property, to

sully the arms of Britons or freemen, employed in the glorious,. and

righteous cause of rescuing and delivering this country from the

usurpation of rebellion, and that no cruelty whatever be offered against

the laws of humanity, but what resistance shall make necessary; and that

whatever provisions and other necessaries be taken for the troops, shall

be paid for immediately; and in case any person, or persons, shall offer

the least violence to the families of such as will join the Royal

Standard, such persons or persons may depend that retaliation will be

made; the horrors of such proceedings, it is hoped, will be avoided by all

true Christians.

Manifestos being the order of the day, Thomas

Rutherford, erstwhile patriot, deriving his commission from the Provincial

congress, though having alienated himself, but signing himself colonel,

also issues one in which he declares that this is "to command, enjoin,

beseech, and require all His Majesty’s faithful subjects within the County

of Cumberland to repair to the King’s Royal standard, at Cross Creek, on

or before the 16th present, in order to join the King’s army; otherwise,

they must expect to fall under the melancholy consequences of a declared

rebellion, and expose themselves to the just resentment of an injured,

though gracious Sovereign."

On February 1st General MacDonald set up the Royal

Standard at Cross Creek, in the Public Square, and in order to cause the

Highlanders all to respond with alacrity manifestos were issued and other

means resorted to in order that the "loyal subjects of His Majesty" might

take up arms, among which nightly balls were given, and the military

spirit freely inculcated. When the day came the Highlanders were seen

coming from near and from far, from the wide plantations on the river

bottoms, and from the rude cabins in the depths of the lonely pine

forests, with broad-swords at their side, in tartan garments and feathered

bonnet, and keeping step to the shrill music of the bag-pipe. There came,

first of all, Clan MacDonald with Clan MacLeod near at hand, with lesser

numbers of Clan MacKenzie, Clan MacRae, Clan MacLean, Clan MacKay, Clan

MacLachlan, and still others,—variously estimated at from fifteen hundred

to three thousand, including about two hundred others, principally

Regulators. However, all who were capable of bearing arms did not respond

to the summons, for some would not engage in a cause where their

traditions and affections had no part. Many of them hid in the swamps and

in the forests. On February 18th the Highland army took up its line of

march for Wilmington and at evening encamped on the Cape Fear, four miles

below Cross Creek.

The assembling of the Highland army aroused the entire

country. The patriots, fully cognizant of what was transpiring, flew to

arms, determined to crush the insurrection, and in less than a fortnight

nearly nine thousand men had risen against the enemy, and almost all the

rest were ready to turn out at a moment’s notice. At the very first menace

of danger, Brigadier General James Moore took the field at the head of his

regiment, and on the 15th secured possession of Rockfish bridge, seven

miles from Cross Creek, where he was joined by a recruit of sixty from the

latter place.

On the 19th the royalists were paraded with a view to

assail Moore on the following night; but he was thoroughly entrenched, and

the bare suspicion of such a project was contemplated caused two

companions of Cotton’s corps to run off with their arms. On that day

General MacDonald sent the following letter to General

Moore:

"Sir: I herewith send the bearer, Donald Morrison, by

advice of the Commissioners appointed by his Excellency Josiah Martin, and

in behalf of the army now under my command, to propose terms to you as

friends and countrymen. I must suppose you unacquainted with the

Governor’s proclamation, commanding all his Majesty’s loyal subject to

repair to the King’s royal standard, else I should have imagined you would

ere this have joined the King’s army now engaged in his Majesty’s service.

I have therefore thought it proper to intimate to you, that in case you do

not, by 12 o’clock to-morrow, join the royal standard, I must consider you

as enemies, and take the necessary steps for the support of legal

authority.

I beg leave to remind you of his Majesty’s speech to

his Parliament, wherein he offers to receive the misled with tenderness

and mercy, from motives of humanity. 1 again beg of you to accept the

proffered clemency. I make no doubt, but you will show the gentleman sent

on this message every possible civilty; and you may depend in return, that

all your officers and men, which may fall into our hands shall be treated

with an equal degree of respect. I have the honor to be, in behalf of the

army, Sir, Your most obedient humble servant,

Don. McDonald.

Head Quarters, Feb. 19, 1776.

His Excellency’s Proclamation is herewith enclosed."

Brigadier General Moore’s answer:

"Sir: Yours of this day I have received, in answer to

which, I must inform you that the terms which you are pleased to say, in

behalf of the army under your command, are offered to us as friends and

countrymen, are such as neither my duty or inclination will permit me to

accept, and which I must presume you too much of an officer to accept of

me. You were very right when you supposed me unacquainted with the

Governor’s proclamation, but as the terms therein proposed are such as I

hold incompatible with the freedom of Americans, it can be no rule of

conduct for me. However, should I not hear farther from you before twelve

o’clock to-morrow by which time I shall have an opportunity of consulting

my officers here, and perhaps Col. Martin, who is in the neighborhood of

Cross Creek, you may expect a more particular answer; meantime you. may be

assured that the feelings of humanity will induce me to shew that civility

to such of your people as may fall into our hands, as I am desirous should

be observed towards those of ours, who may be unfortunate enough to fall

into yours. I am, Sir, your most obedient and very humble servant,

James Moore.

Camp at Rockfish, Feb. 19, 1776."

General Moore, on the succeeding day sent the following

to General MacDonald:

"Sir: Agreeable to my promise of yesterday, I have

consulted the officers under my command respecting your letter, and am

happy in finding them unanimous in opinion with me. We consider ourselves

engaged in a cause the most glorious and honourable in the world, the

defense of the liberties of mankind, in support of which we are determined

to hazard everything dear and valuable and in tenderness to the deluded

people under your command, permit me, Sir, through you to inform them,

before it is too late, of the dangerous and destructive precipice on which

they stand, and to remind them of the ungrateful return they are about to

make for their favorable reception in this country. If this is not

sufficient to recall them to the duty which they owe themselves and their

posterity inform them that they are engaged in a cause in which they

cannot succeed as not only the whole force of this Country, but that of

our neighboring provinces, is exerting and now actually in motion to

suppress them, and which much end in their utter destruction. Desirous,

however, of avoiding the effusion of human blood, I have thought proper to

send you a test recommended by the Continental Congress, which if they

will yet subscribe we are willing to receive them as friends and country-

men. Should this offer be rejected, I shall consider

them as enemies to the constitutional liberties of America, and treat them

accordingly.

I cannot conclude without reminding you, Sir, of the

oath which you and some of your officers took at Newbern on your arrival

to this country, which I imagine you will find is difficult to reconcile

to your present conduct. I have no doubt that the bearer, Capt. James

Walker, will be treated with proper civilty and respect in your camp.

I am, Sir, your most obedient and very humble servant,

James Moore.

Camp at Rockfish, Feb.

20, 1776."

General MacDonald returned the following reply:

"Sir: I received your favor by Captain James Walker,

and observed your declared sentiments of revolt, hostility and rebel-,

lion to the King, and to what I understand to be the constitution of the

country. If I am mistaken future consequences must determine; but while I

continue in my present sentiment, I shall consider myself embarked in a

cause which must, in its consequences, extricate this country from anarchy

and licentiousness. I cannot conceive that the Scottish emigrants, to whom

I imagine you allude, can be under greater obligations to this country

than to the King, under whose gracious and merciful government they alone

could have been enabled to visit this western region: And I trust, Sir, it

is in the womb of time to say, that they are not that deluded and

ungrateful people which you would represent them to be. As a soldier in

his Majesty’s service, I must inform you, if you are to learn, that it is

my duty to conquer, if I cannot reclaim, all those who may be hardy enough

to take up arms against the best of masters, as of Kings. I have the honor

to be, in behalf of the army under my command,

Sir, your most obedient servant,

Don. McDonald.

To the Commanding Officer at Rockfish."

MacDonald realized that he was unable to put his threat

into execution, for he was informed that the minute-men were gathering in

swarms all around him; that Colonel Caswell, at the head of the minute men

of Newbern, nearly eight hundred strong, was marching through Duplin

county, to effect a junction with Moore, and that his communication with

the war ships had been cut off.

Realizing the extremity of his danger, he resolved to

avoid an engagement, and leave the army at Rockfish in his rear, and by

celerity of movement, and crossing rivers at unsuspected places, to

disengage himself from the larger bodies and fall upon the cornmand of

Caswell. Before marching he exhorted his men to fidelity expressed bitter

scorn for the "base cravens who had deserted the night before," and

continued by saying:

"If any amongst you is so faint-hearted as not to serve

with the resolution of conquering or dying, this is the time for such to

declare themselves."

The speech was answered by a general huzza for the

king; but from Cotton’s corps about twenty laid down their arms. He

decamped, with his army at midnight, crossed the Cape Fear, sunk his

boats, and sent a party fifteen miles in advance to secure the bridge over

South river, from Bladen into Hanover, pushing with rapid pace over

swollen streams, rough hills, and deep morasses, hotly pursued by General

Moore. Perceiving the purpose of the enemy General Moore detached Colonels

Lillington and Ashe to reinforce Colonel Caswell, or if that could not be

effected, then they were to occupy Widow Moore’s Creek bridge.

Colonel Caswell designing the purpose of MacDonald

changed his own course in order to intercept his march. On the 23rd the

Highlanders thought to overtake him, and arrayed themselves in the order

of battle, with eighty able-bodied men, armed with broad-swords, forming

the center of the army; but Colonel Caswell being posted at Corbett’s

Ferry could not be reached for want of boats. The royalists were again in

extreme danger; but at a point six miles higher up the Black river they

succeeded in Crossing in a broad shallow boat while MacLean and Fraser,

left with a few men and a drum and a pipe, amused the corps of Caswell.

Colonel Lillington, on the 25th took post on the east

side of Moore’s Creek bridge; and on the next day Colonel Caswell reached

the west side, threw up a slight embankment, and de stroyed a part of the

bridge. A royalist, who had been sent into his camp under pretext of

summoning him to return to his allegiance, brought back the information

that he had halted on the

same side of the river as themselves, and could be

assaulted with advantage. Colonel Caswell was not only a good woodman, but

also a man of superior ability, and believing he had misled the enemy,

marched his column to the east side of the stream, removed the planks from

the bridge, and placed his men behind trees and such embankments as could

be thrown up during the night. His force now amounted to a thousand men,

consisting of the New-bern minute-men, the militia of Craven, Dobbs,

Johnston, and:

Wake counties, and the detachment under Colonel

Lillington. The men of the Neuse region, their officers wearing silver

crescents upon their hats, inscribed with the words, "Liberty or Death,"

were in front. The situation of General MacDonald was again perilous, for

while facing this army, General Moore, with his regulars was close upon

his rear.

The royalists, expecting an easy victory, decided upon

an immediate attack. General MacDonald was confined to his tent by

sickness, and the command devolved upon Major Donald MacLeod, who began

the march at one o’clock on the morning of the 27th, but owing to the time

lost in passing an intervening morass, it was within an hour of daylight

when they reached the west bank of the creek They entered the ground

without resistance. See- ing Colonel Caswell was on the opposite side they

reduced their

columns and formed their line of battle in the woods.

Their rallying cry was, "King George and broadswords," and the signal for

attack was three cheers, the drum to beat and the pipes to play.

While it was still dark Major MacLeod, with a party of

about forty advanced, and at the bridge was challenged by the sentinel,

asking, "Who goes there ?" He answered, "A friend." "A friend to whom ?"

"To the king." Upon this the sentinels bent their faces down to the

ground. Major MacLeod thinking they might be some of his own command who

had crossed the bridge, challenged them in Gaelic; but receiving no reply,

fired his own piece, and ordered his party to fire also. All that remained

of the bridge were the two logs, which had served for sleepers, permitting

only two persons to pass at a time. Donald MacLeod and Captain John

Campbell rushed forward and succeeded in getting over. The Highlanders who

followed were shot down on the logs and

fell into the muddy stream below. Major MacLeod was

mortally wounded, but was seen to rise repeatedly from the ground, waving

his sword and encouraging his men to come on, till twentysix balls

penetrated his body. Captain Campbell also was shot dead, and at that

moment a party of militia, under Lieutenant Slocum, who had forded the

creek and penetrated a swamp on its western bank, fell suddenly upon the

rear of the royalists. The loss of their leader and the unexpected attack

upon their rear threw them into confusion, when they broke and fled. The

battle lasted but ten minutes. The royalists lost seventy killed and

wounded, while the patriots had but two wounded, one of whom recovered.

The victory was lasting and complete. The Highland power was thoroughly

broken. There fell into the hands of the Americans besides eight hundred

and fifty prisoners, fifteen hundred rifles, all of them excellent pieces,

three hundred and fifty guns and short bags, one hundred and fifty swords

and dirks, two medicine chests, immediately from England, one valued at

£300 sterling, thirteen wagons with horses, a box of Johannes and English

guineas, amounting to about $75,000.

Some of the Highlanders escaped from the battlefield by

breaking down their wagons and riding away, three upon a horse. Many who

were taken confessed that they were forced and persuaded contrary to their

inclinations into the service. The soldiers taken were disarmed, and

dismissed to their homes.

On the following day General MacDonald and nearly all

the chief men were taken prisoners, amongst whom was MacDonald of

Kingsborough and his son Alexander. A partial list of those apprehended is

given in a report of the Committee of the Provincial Congress, reported

April 20th and May 10th on the guilt of the Highland and Regulator

officers then confined in Halifax gaol, finding the prisoners were of four

different classes, viz.:

First, Prisoners who had served in Congress.

Second, Prisoners who had signed Tests or Associations.

Third, Prisoners who had been in arms without such circumstances

Fourth, Prisoners under suspicious circumstances.

The Highlanders coming under the one or the other of

these classes are given in the following order:

Farquhard Campbell, Cumberland county.

Alexander McKay, Capt. of 38 men, Cumberland county.

Alexander McDonald (Condrach), Major of a regiment.

Alexander Morrison, Captain of a company of 35 men.

Alexander MacDonald, son of Kingsborough, a volunteer, Anson county.

James MacDonald, Captain of a company of 25 men.

Alexander McLeod, Captain of a company of 32 men.

John MacDonald, Captain of a company of 40 men.

Alexander McLeod, Captain of a company of 16 men.

Murdoch McAskell, Captain of a company of 34 men.

Alexander McLeod, Captain of a company of 16 men.

Angus McDonald, Captain of a company of 30 men.

Neill McArthur, Freeholder of Cross Creek, Captain of a company of 55 men.

Francis Frazier, Adjutant to General MacDonald’s Army John McLeod,. of

Cumberland county, Captain of company of 35 men.

John McKinzie, of Cumberland county, Captain of company of 43 men.

Kennith Macdonald, Aid-de-camp to General Macdonald.

Murdoch McLeod, of Anson county, Surgeon to General Macdonald’s Army

Donald McLeod, of Anson county, Lieutenant in Captain Morrison’s Company.

Norman McLeod, of Anson county, Ensign in James McDonald’s company.

John McLeod, of Anson county, Lieutenant in James McDonald’s company.

Laughlin McKinnon, freeholder in Cumberland county, Lieutenant in Col.

Rutherford’s corps.

James Munroe, freeholder in Cumberland county, Lieutenant in Capt. McRay’s

company.

Donald Morrison, Ensign to Capt. Morrison’s company.

John McLeod, Ensign to Capt. Morrison’s company. -

Archibald McEachern, Bladen county, Lieutenant to Capt. McArthur’s

company.

Rory McKinnen, freeholder Anson county, volunteer.

Donald McLeod, freeholder Cumberland county, Master to two Regiments,

General McDonald’s Army.

Donald Stuart, Quarter Master to Col. Rutherford’s Regiment.

Allen Macdonald of Kingsborough, freeholder of Anson county, Col.

Regiment.

Duncan St. Clair.

Daniel McDaniel, Lieutenant in Seymore York’s company.

Alexander McRaw, freeholder Anson county, Capt. company 47 men.

Kenneth Stuart, Lieutenant Capt Stuart’s company

Collin Mclver, Lieutenant Capt. Leggate’s company.

Alexander Maclaine, Commissary to General Macdonald’s Army.

Angus Campbell, Captain company 30 men.

Alexander Stuart, Captain company 30 men.

Hugh McDonald, Anson county, volunteer.

John McDonald, common soldier.

Daniel Cameron, common soldier.

Daniel McLean, freeholder, Cumberland county, Lieutenant to Angus

Campbell’s company.

Malcolm McNeill, recruiting agent for General Macdonald’s Army, accused of

using compulsion.

The following is a list of the prisoners sent from

North Carolina to Philadelphia, enclosed in a letter of April 22,

1776:

1 His Excellency Donald McDonald Esqr Brigadier General of the Tory

Army and Commander in Chief in North Carolina.

2 Colonel Allen McDonald (of Kingsborough) first in Commission of

Array and second in Command

3 Alexander McDonald son of Kingsborough

4 Major Alexander McDonald (Condrack)

5 Capt Alexander McRay

6 Capt John Leggate

7 Capt James McDonald

8 Capt Alexr. McLeod

9 Capt Alexr. Morrison

10 Capt John McDonald

11 Capt A1exr. McLeod

12 Capt Murdoch McAskell

13 Capt Alexander McLeod

14 Capt Angus McDonald

15 Capt Neil McArthur

16 Capt James Mens of the light horse.

17 Capt John McLeod

18 Capt Thos. Wier

19 Capt John McKenzie

20 Lieut John Murchison

21 Kennith McDonald, Aid de Camp to Genl McDonald

22 Murdock McLeod, Surgeon

23 Adjutant General John Smith

24 Donald McLeod Quarter Master

25 John Bethune Chaplain

26 Farquhard Campbell late a delegate in the provincial Congress—Spy and

Confidential Emissary of Governor Martin."

Some of the prisoners were discharged soon after their

arrest, by making and signing the proper oath, of which the following is

taken from the Records:

"Oath of Malcolm McNeill and Joseph Smith. We Malcolm

McNeil and Joseph Smith do Solemly Swear on the Holy Evangelists of

Almighty God that we will not on any pretence whatsoever take up or bear

Arms against the Inhabitants of the United States of America and that we

will not disclose or make known any matters within our knowledge now

carrying on within the United States and that we will not carry out more

than fifty pounds of Gold & Silver in value to fifty pounds Carolina

Currency. So help us God.

Malcolm McNeill,

Joseph Smith.

Halifax, 13th Augt., 1776.

The North Carolina Provincial Congress on March 5,

1776, "Resolved, That Colonel Richard Caswell send, under a sufficient

guard, Brigadier General Donald McDonald, taken at the battle of Moore’s

Creek Bridge, to the Town of Halifax, and there to have him committed a

close prisoner in the jail of the said Town, until further orders."

The same Congress, held in Halifax April 5th,

"Resolved, That General McDonald be admitted to his parole upon the

following conditions: That he does not go without the limits of the Town

of Halifax; that he does not directly or indirectly, while a prisoner,