|

The attitude of the Highlanders during the

Revolutionary War was not of such a nature as to bring them prominently

into -view in the cause of freedom. Nor was it the policy of the

American statesmen to cater to race distinctions and prejudices. They did

not regard their cause to be a race war. They fought for freedom without

regard to their origin, believing that a just Providence would smile upon

their efforts. Many nationalities were represented in the American army.

Men left their homes in the Old World, purposely to engage in the cause of

Independence, some of whom gained immortal renown, and will be remembered

with honor by generations yet unborn. As has been already noted, there

were natives of the Highlands of Scotland, who had made America their home

and imbibed the principles of political liberty, and early identified

themselves with the cause of their adopted country. The lives of some of

these patriots are herewith

imperfectly sketched.

GENERAL ALEXANDER M’DOUGALL.

There are few names in the annals of

the American Revolution upon which one

can linger with more satisfaction than that of

the gallant and true—hearted Alexander McDougall. As early as August 20,

1775, Washington wrote to General Schuyler concerning him: "his zeal is

unquestionable." Writing to General McDougall, May 23, 1777,

Washington says: I wish every officer in the army could appeal to his own

heart and find the same principles of conduct, that I am persuaded actuate

you." The same writing to Thomas Jefferson, August 1, 1786, lamented the

brave "soldier and disinterested

patriot," and exclaimed, "Thus some of the pillars of the revolution

fall."

Alexander

McDougall Alexander

McDougall was born in the island

of Islay in Scotland, in 1731, being the son of Ranald McDougall, who

emigrated to the province of New York in 1735. The father purchased a

small farm near the city of New York, and there peddled milk, in which

avocation he was assisted by his son., who never was ashamed of the

employment of his youth. Alexander was a keen observer of passing events

and took great interest in the game of politics. With vigilance he watched

the aggressive steps of the royal government; and when the Assembly, in

the winter of 1769, faltered in its opposition to the usurpations of the

crown and insulted the people by rejecting a proposition authorizing the

vote by ballot, and by entering on the favorable consideration of a bill

of supplies for troops quartered in the city to overawe the inhabitants,

he issued an address, under the title of "A Son of Liberty to the Betrayed

Inhabitants of the Colony," in which he contrasted the Assembly with the

legislative bodies in other parts of the country, and held up their

conduct to unmitigated and just indignation. The bold and deserved rebuke

was laid before the house by its speaker, and, with the exception of

Philip Schuyler, every member voted that it was "an infamous and seditious

libel." A proclamation for the discovery of the author was issued by the

governor, and it being traced to Alexander McDougall, he was arrested in

February, 1770, and refusing to give bail was committed to prison by order

of chief justice Horsmanden. As he was being carried to prison, clearly

reading in the signs about him the future of the country, he exclaimed, "I

rejoice that I am the first sufferer for liberty since the commencement of

our glorious struggle." During the two months of his confinement he was

overrun with visitors. He poured forth continued appeals to the people,

and boldly avowed his revolutionary opinions. In every circle his case was

the subject of impassioned conversation, and in an especial manner he

became the idol of the masses. A

packed jury found an indictment against him, and on December 20th he was

arraigned at the bar of the Assembly on the same charge, on which occasion

he was defended by George Clinton, afterwards the first governor of the

State of New York. In the course of the following month a writ of habeas

corpus was sued out, but without result, and he was not liberated until

March 4, 1771, when the assembly was prorogued. When the Assembly

attempted to extort from him a humiliating recantation, he undauntingly

answered their threat, that "rather than resign my rights and privileges

as a British subject, I would suffer my right hand to be cut off at the

bar of the house." When set at liberty he entered into correspondence with

the master-spirits in all parts of the country; and when the celebrated

meetings in the fields were held, on July 6, 1774, preparatory to the

election of the New York delegates to the First General Congress, he was

called to preside, and resolutions prepared by him were adopted, pointing

out the mode of choosing deputies, inveighing against the Boston Port

Bill, and urging upon the proposed congress the prohibition of all

commercial intercourse with Great Britain. In March 1775, he was a member

of the Provincial Convention, and was nominated as one of the candidates

for the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, but was not elected. In the

same year he received a commission as colonel of the 1st New York

regiment, and on August 9, 1776, was created brigadier-general. On the

evening of the 29th of the same month he was selected by Washington to

superintend the embarkation of the troops from Brooklyn; was actively

engaged on Chatterton’s Hill and in various places in New Jersey; and when

General William Heath, in the spring of 1777, left Peekskill to assume the

command of the eastern department, he succeeded that officer, but was

compelled, by a superior force under Sir William Howe, to retreat from the

town, after destroying a considerable supply of stores, on March 23rd.

After the battle of Germantown, in which he participated, Washington,

writing to the president of Congress, under date of October 7, 1777, says:

"I cannot however omit this

opportunity of recommending General McDougall to their notice. This

gentleman, from the time of his appointment as brigadier, from his

abilities, military knowledge, and approved bravery, has every claim to

promotion."

On the 20th of the same month he was

commissioned major-general. On March 16, 1778, he was directed to assume

the command of the different posts on the Hudson, and, with activity,

pursued the construction of the fortifications in the Highlands, and,

after the flight of General Arnold, was put in command of West Point,

October 5, 1780. Near the close of that year he was called upon by New

York to repair to Congress as one of their representatives. It was a

critical moment, and Washington urged his acceptance of the post;

accordingly he took his seat in the Congress the next January. Congress

having organized an executive department, in 1781, General McDougall was

appointed Minister of Marine. He did not remain long in Philadelphia, for

his habits, friendships, associations and convictions of duty recalled him

to the camp. The confidence felt in his integrity and good judgment by all

classes in the service, was such, that when the army went into winter

quarters at Newburgh, in 1783, he was chosen at the head of the delegation

to Congress to represent their grievances. The same year, after the close

of the war, he was elected to represent the Southern District in the

senate of New York and continued a member of that body until his death,

which occurred in the city of New York June 8, 1786. At the time of his

decease, General McDougall was president of the Bank of New York. In

politics he adhered to the Hamilton party.

GENERAL LACHLAN M’INTOSH.

The

history of the emigration of John Mohr McIntosh to Georgia, and the

settlement upon the Alatamaha, where now stands the city of Darien, has

already been recorded. The second son of John Mohr was Lachlan, born near

Raits in Badenoch, Scotland, March 17, 1725, and consequently was eleven

years old at the time he emigrated to America. As has been already noted

John Mohr McIntosh was captured by the Spaniards at Fort Moosa, carried to

Spain, and after several years. returned in broken health. The

history of the emigration of John Mohr McIntosh to Georgia, and the

settlement upon the Alatamaha, where now stands the city of Darien, has

already been recorded. The second son of John Mohr was Lachlan, born near

Raits in Badenoch, Scotland, March 17, 1725, and consequently was eleven

years old at the time he emigrated to America. As has been already noted

John Mohr McIntosh was captured by the Spaniards at Fort Moosa, carried to

Spain, and after several years. returned in broken health.

Both Lachlan and his elder brother

William were placed as cadets in the regiment by General Oglethorpe. When

General Oglethorpe made his final preparations for his return to England,

the two young brothers were found hid away in the hold of an— other

vessel, for they had heard of the attempts then being made by Prince

Charles to regain the throne of his ancestors, and they hoped to regain

something that the family of Borlam had lost, of which they were members.

General Oglethorpe had the two boys brought to his cabin; he spoke to them

of the friendship he had entertained for their father, of the kindness he

had shown to themselves, of the hopelessness of every attempt of the house

of Stuart, of their own folly in engaging in this wild and desperate

struggle, of his own duty as an officer of the house of Brunswick; but if

they would go ashore, their secret should be his. He received their pledge

and they never saw him again.

At that time the means of education

in Georgia were limited, yet under his mother's care Lachlan McIntosh was

well instructed in English, mathematics and other branches necessary for

future military use. Lachlan sought the promising field of enterprise in

Charleston, South Carolina, where the fame of his father’s gallantry and

misfortunes secured to him a kind reception from Henry Laurens, afterwards

president of Congress, and the first minister of the United States to

Holland. In the house of that patriot he remained several years, and

contracted friendships that lasted while he lived, with some of the

leading citizens of the southern colonies. having adopted the profession

of surveyor,

and married, he returned to Georgia,

where he acquired a wide and honorable reputation. On account of his views

concerning certain lands between the Alatamaha and St. Mary’s rivers which

did not coincide with those of Governor Wright of Georgia, it afforded the

latter a pretence, for a long and deliberate opposition to the interests

of Lachlan Mclntosh, which gradually schooled him for the approaching

conflict between England and her American colonies. When that event began

to dawn upon the people every eye in Georgia was turned to General

McIntosh as the leader of whatever force that province might bring into

the struggle. When, therefore, the revolutionary government was organized

and an order was made for raising a regiment was adopted, Lachlan McIntosh

was made colonel commandant; and when the order was issued for raising

three other regiments, in September, 1776, he was immediately appointed

brigadier-general commandant. About this time Button Gwinnett was elected

governor, who had been an unsuccessful competitor for the command of the

troops. He was a man unrestrained by any honorable principles, and used

his official authority in petty persecutions of General McIntosh and his

family. The general bore all this patiently until his opponent ceased to

be governor, when he communicated to him the opinion he entertained of his

conduct. He received a challenge, and in a duel wounded him mortally.

General McIntosh now applied, through his friend Colonel Henry Laurens,

for a place in the Continental army, which was granted, and with his staff

was invited to join the commander-in-chief. He soon won the confidence of

Washington, and for a long time was placed in his front, while watching

the superior forces of Sir William Howe in Philadelphia.

While the army was in winter

quarters at Valley Forge, the attention of the government was called to

the exposed condition of the western frontier, upon which the British was

constantly exciting the Indians to the most terrible atrocities. It was

determined that General McIntosh should command an expedition against the

Indians on the Ohio. In a letter to the President of Congress, dated May

12, 1778, Washington says:

"After much consideration upon the

subject, I have appointed General McIntosh to command at Fort Pitt, and in

the western country, for which he will set out as soon as he can

accommodate his affairs. I part with this gentleman with much reluctance,

as I esteem him an officer of great worth and merit, and as I know his

services here are and will be materially wanted. His firm disposition and

equal justice, his assiduity and good understanding, added to his being a

stranger to all parties in that quarter, pointed him out as a proper

person."

With a reinforcement of five hundred

men General McIntosh marched to Fort Pitt, of which he assumed the

command, and in a short time he gave repose to all western Pennsylvania

and Virginia. In the spring of 1779, he completed arrangements for an

expedition against Detroit, but in April was recalled by Washington to

take part in the operations proposed for the south, where his knowledge of

the country, added to his stirling qualities, promised him a useful field.

He joined General Lincoln in Charleston, and every preparation in their

power was made for the invasion of Georgia, then in possession of the

British, as soon as the French fleet under count D’Estaing should arrive

on the coast. General McIntosh marched to Augusta, took command of the

advance of the troops, and proceeding down to Savannah, drove in all the

British outposts. Expecting to be joined by the French, he marched to

Beauly, where count D’Estaing effected a landing on September 12th, 13th,

and 14th, and on the 15th was joined by General Lincoln. General McIntosh

pressed for an immediate at tack, but the French admiral refused. In the

very midst of the siege the French fleet put to sea, leaving Generals

Lincoln and Mcintosh to retreat to Charleston, where they were besieged by

an overwhelming force under Sir Henry Clinton, to whom the city was

surrendered on May 12, 1780. With this event the military life of General

McIntosh closed. He was long detained a prisoner of war, and when finally

released, retired with his family to Virginia, where he remained until the

British troops were driven from Savannah. Upon his return to Georgia, he

found his personal property wasted and his real estate much diminished in

value. From that time to the close of his life, in a great measurer he

lived in retirement and comparative poverty until his death, which took

place at Savannah, February 20, 1806.

GENERAL ARTHUR ST. CLAIR.

The

life of Major General Arthur St. Clair was a stormy one, full of

disappointments, shattered hopes, and yet honored and revered for the

distinguished and disinterested services he performed. He was a near

relative of the then earl of Roslin, and was born in 1734, in the town of

Thurso, Caithness in Scotland. He inherited the fine personal appearance

and manly traits of the St. Clairs. After graduating at the University of

Edinburgh, he entered upon the study of medicine under the celebrated

Doctor William Hunter of London; but receiving a large sum of money from

his mother’s estate in 1757, he changed

his purpose and sought adventures in a military life, and the same year

entered the service of the king of Great Britain, as ensign in the 60th or

Royal American Regiment of Foot. In May of the succeeding year he was with

General Amherst before Louisburg. Gathered there were men soon to become

famous among whom were Wolfe, Montcalm, Murray and Lawrence. For gallant

conduct Arthur St. Clair received a lieutenant’s commission, April

17, 1759, and was with General Wolfe in that brilliant

struggle before Quebec, in September of the same year, and soon after was

made a captain. In 1760 he married at Boston, Miss Phoebe Bayard, with a

fortune of £40,000, which added to his own made him a man of wealth. On

April 16, 1762, he resigned his commission in the army, and soon after led

a colony of Scotch settlers to the Ligonier Valley, in Pennsylvania, where

he purchased for himself one thousand acres of land. Improvements

everywhere sprang up under his guiding genius. He held various offices,

among which was member of the Proprietory Council of Pennsylvania, and

colonel of militia. The mutterings which preceded the American Revolution

were early heard in the beautiful valley of the Ligonier. Colonel St.

Clair was not slow to take action, and espoused the cause of the patriots

with all the intensity of his character, and never, even for a moment,

swerved in the cause. He was destined to receive the enduring friendship

of Washington, La Fayette, Hamilton, Schuyler, Wilson, Reed, and others of

the most distinguished patriots of the Revolution. Early in the year 1776,

he resigned his civil offices, and led the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment in

the invasion of Canada, and on account of the remarkable skill there

displayed in saving from capture the army of General Sullivan, he received

the rank of brigadier-general, August 6, 1776. He claimed to have pointed

out the Quaker road to Washington on the night before the battle of

Princeton. On account of his meritorious services in that battle, he was

made a major-general, February 19, 1777. On the advance of General

Burgoyne, who now threatened the great avenue from the north, General St.

Clair was placed in command of Ticonderoga. Discovering that he could not

hold the position, with great reluctance he ordered the fort evacuated. A

great clamor was raised against him, especially in the New England States,

and on account of this he was suspended, and a court-martial ordered.

Retaining the confidence of Washington he was a volunteer aid to that

commander at the battle of Brandywine. In September 1778, the

court-martial acquited him of all the charges. He was on the court-martial

that condemned Major John Andre, adjutant-general of the British army, as

a spy, who had been actively implicated in the treason of Benedict Arnold,

and soon after was placed in command of West Point. He assisted in

quelling the mutiny of the Pennsylvania line, and shared in the crowning

glory of the Revolution, the capture of the British army under lord

Cornwallis at Yorktown. Soon afterwards General St. Clair retired to

private life, but his fellow-citizens soon determined otherwise. In 1783

he was on the board of censors for Pennsylvania, and afterwards chosen

vendue—master of Philadelphia; in 1786 was elected a member of Congress,

and in 1787 was president of that body, which at that time, was the

highest office in America. In 1788 he was elected governor of the North

West Territory, which imposed upon him the duty of governing, organizing,

and bringing order out of chaos, over that region of country. In 1791,

Washington made him commander—in—chief of the army, and in the autumn,

with an ill—appointed force, set out, under the direct orders from Henry

Knox, then Secretary of War, on an expedition against the Indians, but met

with an overwhelming defeat on November 4th. The disaster was investigated

by Congress, and the general was justly exonerated from all blame. He

resigned his commission as general in 1792, but continued in office as

governor until 1802, when he was summarily dismissed by Thomas Jefferson,

then president. In poverty he retired to a log-house which overlooked the

valley he had once owned. In vain he pressed his claims against the

government for the expenditures he had made during the Revolution, in aid

of the cause. In 1812 he published his "Narrative." In 1813 the

legislature of Pennsylvania granted him an annuity of $400, and finally

the general government gave him a pension of $60 per month. He died at

Laural Hill, Pennsylvania, August 31, 1818, from injuries received by

being thrown from a wagon. The

life of Major General Arthur St. Clair was a stormy one, full of

disappointments, shattered hopes, and yet honored and revered for the

distinguished and disinterested services he performed. He was a near

relative of the then earl of Roslin, and was born in 1734, in the town of

Thurso, Caithness in Scotland. He inherited the fine personal appearance

and manly traits of the St. Clairs. After graduating at the University of

Edinburgh, he entered upon the study of medicine under the celebrated

Doctor William Hunter of London; but receiving a large sum of money from

his mother’s estate in 1757, he changed

his purpose and sought adventures in a military life, and the same year

entered the service of the king of Great Britain, as ensign in the 60th or

Royal American Regiment of Foot. In May of the succeeding year he was with

General Amherst before Louisburg. Gathered there were men soon to become

famous among whom were Wolfe, Montcalm, Murray and Lawrence. For gallant

conduct Arthur St. Clair received a lieutenant’s commission, April

17, 1759, and was with General Wolfe in that brilliant

struggle before Quebec, in September of the same year, and soon after was

made a captain. In 1760 he married at Boston, Miss Phoebe Bayard, with a

fortune of £40,000, which added to his own made him a man of wealth. On

April 16, 1762, he resigned his commission in the army, and soon after led

a colony of Scotch settlers to the Ligonier Valley, in Pennsylvania, where

he purchased for himself one thousand acres of land. Improvements

everywhere sprang up under his guiding genius. He held various offices,

among which was member of the Proprietory Council of Pennsylvania, and

colonel of militia. The mutterings which preceded the American Revolution

were early heard in the beautiful valley of the Ligonier. Colonel St.

Clair was not slow to take action, and espoused the cause of the patriots

with all the intensity of his character, and never, even for a moment,

swerved in the cause. He was destined to receive the enduring friendship

of Washington, La Fayette, Hamilton, Schuyler, Wilson, Reed, and others of

the most distinguished patriots of the Revolution. Early in the year 1776,

he resigned his civil offices, and led the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment in

the invasion of Canada, and on account of the remarkable skill there

displayed in saving from capture the army of General Sullivan, he received

the rank of brigadier-general, August 6, 1776. He claimed to have pointed

out the Quaker road to Washington on the night before the battle of

Princeton. On account of his meritorious services in that battle, he was

made a major-general, February 19, 1777. On the advance of General

Burgoyne, who now threatened the great avenue from the north, General St.

Clair was placed in command of Ticonderoga. Discovering that he could not

hold the position, with great reluctance he ordered the fort evacuated. A

great clamor was raised against him, especially in the New England States,

and on account of this he was suspended, and a court-martial ordered.

Retaining the confidence of Washington he was a volunteer aid to that

commander at the battle of Brandywine. In September 1778, the

court-martial acquited him of all the charges. He was on the court-martial

that condemned Major John Andre, adjutant-general of the British army, as

a spy, who had been actively implicated in the treason of Benedict Arnold,

and soon after was placed in command of West Point. He assisted in

quelling the mutiny of the Pennsylvania line, and shared in the crowning

glory of the Revolution, the capture of the British army under lord

Cornwallis at Yorktown. Soon afterwards General St. Clair retired to

private life, but his fellow-citizens soon determined otherwise. In 1783

he was on the board of censors for Pennsylvania, and afterwards chosen

vendue—master of Philadelphia; in 1786 was elected a member of Congress,

and in 1787 was president of that body, which at that time, was the

highest office in America. In 1788 he was elected governor of the North

West Territory, which imposed upon him the duty of governing, organizing,

and bringing order out of chaos, over that region of country. In 1791,

Washington made him commander—in—chief of the army, and in the autumn,

with an ill—appointed force, set out, under the direct orders from Henry

Knox, then Secretary of War, on an expedition against the Indians, but met

with an overwhelming defeat on November 4th. The disaster was investigated

by Congress, and the general was justly exonerated from all blame. He

resigned his commission as general in 1792, but continued in office as

governor until 1802, when he was summarily dismissed by Thomas Jefferson,

then president. In poverty he retired to a log-house which overlooked the

valley he had once owned. In vain he pressed his claims against the

government for the expenditures he had made during the Revolution, in aid

of the cause. In 1812 he published his "Narrative." In 1813 the

legislature of Pennsylvania granted him an annuity of $400, and finally

the general government gave him a pension of $60 per month. He died at

Laural Hill, Pennsylvania, August 31, 1818, from injuries received by

being thrown from a wagon.

Years afterwards Judge Burnet wrote,

declaring him to have been "unquestionably a man of superior talents, of

extensive information, and of great uprightness of purpose, as well as

suavity of manners. * * * He had been accustomed from infancy to mingle in

the circles of taste and refinement, and had acquired a polish of manners,

and a habitual respect for the feelings of others, which might be cited as

a specimen of genuine politeness." [Notes on the North-Western Territory,

p. 378.]

In 1870 the State of Ohio purchased

the papers of General St. Clair, and in 1882 these were published in two

volumes, containing twelve hundred and seventy pages.

SERGEANT DONALD M ‘DONALD.

The lives of men who have won a

great name on the field of battle throw a glamor over themselves which is

both interesting and fascinating: and those treading the same path but cut

off in their career are forgotten. However, the American Revolution

affords many acts of heroism performed by those who did not command

armies, some of whom performed many acts worthy of record. Perhaps, among

the minor officers none had such a successful run of brilliant exploits as

Sergeant Macdonald, many of which are sufficiently well authenticated.

Unfortunately the essential particulars relating to him have not been

preserved. The warlike deeds which he exhibited are recorded in the "Life

of General Francis Marion" by General Horry, of Marion’s brigade, and

Weems. Just how far Weems romanced may never be known, but in all

probability what is related concerning Sergeant Macdonald is practically

true, save the shaping up of the story.

Sergeant Macdonald is represented to

have been a son of General Donald Macdonald, who headed the Highlanders in

North Carolina, and met with an overwhelming defeat at Moore’s Creek

Bridge. The son was a remarkably stout, red-haired young Scotsman, cool

under the most trying difficulties, and brave without a fault. Soon after

the defeat and capture of his father he joined the American troops and

served under General Horry. One day General Horrv asked him why he had

entered the service of the patriots. In substance he made the following

reply:

"Immediately on the misfortune of my

father and his friends at the Great Bridge, I fell to thinking what could

be the cause; and then it struck me that it must have been owing to their

own monstrous ingratitude. ‘Here now,’ said I to myself, ‘is a parcel of

people, meaning my poor father and his friends, who tied from the

murderous swords of the English after the massacre at Culloden. Well, they

came to America, with hardly anything but their poverty and mournful

looks. But among this friendly people that was enough. Every eve that saw

us, had pity: and every hand was reached out to assist. They received us

in their houses as though we had been their own unfortunate brothers. They

kindled high their hospitable fires for us, and spread their feasts, and

bid us eat and drink and banish our sorrows, for that we were in a land of

friends. And so indeed, we found it; for whenever we told of the woeful

battle of Culloden, and how the English gave no quarter to our unfortunate

countrymen, but butchered all they could overtake, these generous people

often gave us their tears, and said, ‘O! that we had been there to aid

with our rifles, then should many of these monsters have bit the ground.’

They received us into the bosoms of their peaceful forests, and gave us

their lands and their beauteous daughters in marriage, and we became rich.

And yet, after all, soon as the English came to America, to murder this

innocent people, merely for refusing to be their slaves, then my father

and friends, forgetting all that the Americans had done for them, went and

joined the British, to assist them to cut the throats of their best

friends! Now,’ said I to myself, ‘if ever there was a time for God to

stand up to punish ingratitude, this was the time.’ And God did stand up;

for he enabled the Americans to defeat my father and his friends most

completely. But, instead of murdering the prisoners as the English had

done at Culloden, they treated us with their usual generosity. And now

these are the people I love and will fight for as long as I live."

The first notice given of the

sergeant was the trick which he played on a royalist. As soon as he heard

that Colonel Tarleton was encamped at Monk’s Corner, he went the next

morning to a wealthy old royalist of that neighborhood, and passing

himself for a sergeant in the British corps, presented Colonel Tarleton’s

compliments with the request that he would send him one of his best horses

for a charger, and that he should not lose by the gift.

"Send him one of my finest horses !"

cried the old traitor with eyes sparkling with joy. "Yes, Mr. Sergeant,

that I will, by gad! and would send him one of my finest daughters too,

had he but said the word. A good friend of the king, did he call me, Mr.

Sergeant? yes, God save his sacred majesty, a good friend I am indeed, and

a true. And, faith, I am glad too, Mr. Sergeant, that colonel knows it.

Send him a charger to drive the rebels, hey? Yes, egad will I send him

one, and as proper a one too as ever a soldier straddled. Dick! Dick! I

say you Dick !"

"Here, massa, here! here Dick !"

"Oh, you plaguey dog! so I must

always split my throat with bawling, before I can get you to answer hey ?"

"High, massa, sure Dick always

answer when he hear massa hallo !"

"You do, you villian, do you? Well

then run! jump, fly, you rascal, fly to the stable, and bring me out Selim,

my young Selim! do you hear? you villiam, do you hear?"

"Yes, massa, be sure !"

Then turning to the sergeant he went

on:

Well, Mr. Sergeant, you have made me

confounded glad this morning, you may depend. And now suppose you take a

glass of peach; of good old peach, Mr. Sergeant? do you think it would do

you any harm ?"

"Why, they say it is good of a rainy

morning, sir," replied the sergeant.

"O yes, famous of a rainy morning,

Mr. Sergeant! a mighty antifogmatic. It prevents you the ague, Mr.

Sergeant; and clears a man’s throat of the cobwebs, sir."

God bless your honor !" said the

sergeant as he turned off a bumper.

Scarcely had this conversation

passed when Dick paraded Selim; a proud, full-blooded, stately steed, that

stepped as though he were too lofty to walk upon the earth. Here the old

man brightening up, broke out again:

"Aye! there, Mr. Sergeant, there is

a horse for you! isn’t he, my boy?"

"Faith, a noble animal, sir,"

replied the sergeant.

"Yes, egad! a noble animal indeed; a

charger for a king, Mr. Sergeant! Well, my compliments to Colonel

Tarleton; tell him I’ve sent him a horse, my young Selim, my grand Turk,

do you hear, my son of thunder? And say to the colonel that I don’t grudge

him either, for egad! he’s too noble for me, Mr. Sergeant. I’ve no work

that’s fit for him, sir; no sir, if there’s any work in all this country

that’s good enough for him but just that which he is now going on; the

driving the rebels out of the land."

He had Selim caparisoned with his

elegant new saddle and holsters, with his silver-mounted pistols. Then

giving Sergeant Macdonald a warm breakfast, and loaning him his great

coat, he sent him off, with the promise that he would, the next morning,

come and see how Colonel Tarleton was pleased with Selim. Accordingly he

waited on the English colonel, told him his name with a smiling

countenance; but, to his mortification received no special notice. After

partially recovering from his embarrassment he asked Colonel Tarleton how

he liked his charger.

"Charger, sir ?" said the colonel.

"Yes, sir, the elegant horse I sent

you yesterday."

"The elegant horse you sent me,

sir?"

"Yes, sir, and by your sergeant,

sir, as he called himself."

"An elegant horse! and by my

sergeant? Why really, sir, I—I—I don't understand all this."

"Why, my dear, good sir, did you not

send a sergeant yester— day with your compliments to me, and a request

that I would send you my very best horse for a charger, which I did ?"

"No, sir, never! replied the

colonel; "I never sent a sergeant on any such errand. Nor till this moment

did I ever know that there existed on earth such a being as you."

The old man turned black in the

face; he shook throughout; and as soon as he could recover breath and

power of speech, he broke out into a torrent of curses, enough to make one

shudder at his blasphemy. Nor was Colonel Tarleton much behind him when he

learned what a valuable animal had slipped through his hands.

When Sergeant Macdonald was asked

how he could reconcile the taking of the horse he replied:

"Why, sir, as to that matter, people

will think differently; but for my part I hold that all is fair in war;

and besides, sir, if I had not taken him Colonel Tarleton, no doubt, would

have got him. And then, with such a swift strong charger as this he might

do us as much harm as I hope to do them."

Harm he did with a vengeance; for he

had no sense of fear; and for strength he could easily drive his sword

through cap and skull of an enemy with irresistible force. He was fond of

Selim, and kept him to the top of his metal; Selim was not much his

debtor; for, at the first glimpse of a red-coat, he would paw, and champ

his iron bit with rage; and the moment of command, he was off among them

like a thunderbolt. The gallant Highlander never stopped to count the

number, but would dash into the thickest of the fight, and fall to hewing

and cutting down like an uncontrollable giant.

General Horry, when lamenting the

death of his favorite sergeant said that the first time he saw him fight

was when the British held Georgetown; and with the sergeant the two set

out alone to reconnoitre. The two concealed themselves in a clump of pines

near the road, with the enemy’s lines in full view. About sunrise five

dragoons left the town and dashed up the road towards the place where the

heroes were concealed. The face of Sergeant Macdonald kindled up with the

joy of battle. "Zounds, Macdonald," said General Horry, "here’s an odds

against us, five to two." "By my soul now captain," he replied, "and let

‘em come on. Three are welcome to the sword of Macdonald." When the

dragoons were fairly opposite, the two, with drawn sabres broke in upon

them like a tornado. The panic was complete; two were immediately

overthrown, and the remaining three wheeled about and dashed for the town,

applying the whip and spur to their steeds. The sergeant mounted upon the

swift-footed Selim out-distanced his companion, and single-handed cut down

two of the foe. The remaining one would have met a like fate had not the

guns of the fort protected him. Although quickly pursued by the relief,

the sergeant had the address to bring off an elegant horse of one of the

dragoons whom he had killed.

A day or two after the victory of

General Marion over Colonel Tynes, near the Black river, General Horry

took Captain Baxter, Lieutenant Postell and Sergeant Macdonald, with

thirty privates, to see if some advantage could not be gained over the

enemy near the lines of Georgetown. While partaking of a meal at the house

of a planter, a British troop attempted to surprise them. The party leaped

to their saddles and were soon in hot pursuit of the foe. While all were

excellently mounted, yet no horse could keep pace with Selim. He was the

hindmost when the race began, but with widespread nostrils, long extended

neck, and glaring eyeballs, he seemed to fly over the course. Coming up

with the enemy Sergeant Macdonald drew his claymore, and rising on his

stirrups, with high-uplifted arm, he waved it three times in circles over

his head, and then with terrific force brought it down upon the fleeing

dragoon. One of the British officers snapped his pistol at him, but before

he could try another the sergeant cut him down. Immediately after, at a

blow apiece, three more dragoons were brought to the earth by the

resistless clay-more. Of the twenty-five, not a man escaped, save one

officer, who struck off at right angles, for a swamp, which he gained and

so cleared himself. So frightened was Captain Meriot, the British officer,

that his hair, from a bright auburn, before night, had turned gray.

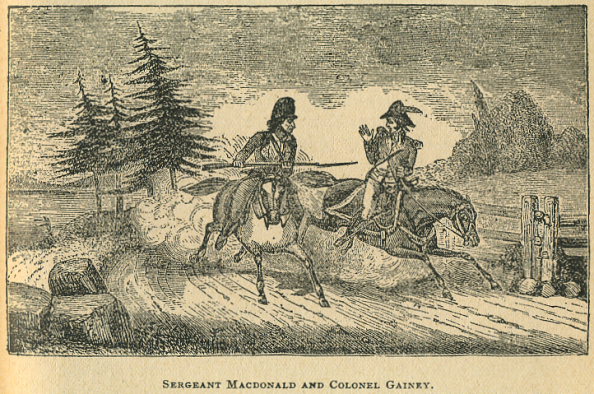

On the following day General Horry

encountered one third of Colonel Gainey’s men, and in the encounter the

latter lost one half his men who were in the action. In the conflict, as

usual the sergeant performed prodigies of valor. Later in the day Colonel

Gainey’s regiment again commenced the attack, when Sergeant Macdonald made

a dash for the leader, in full confidence of getting a gallant charger.

Colonel Gainey proved to have been well mounted; but the sergeant,

regarding but the one enemy passed all others. He afterwards said he could

have slain several in the charge, but wished for no meaner object than

their leader. Only one, who threw himself in the way, became his victim,

whom he shot down as they went at full speed along the Black river road.

When they reached the corner of Richmond fence, the sergeant had gained so

far upon his enemy, as to be able to plunge his bayonet into his back. The

steel parted from the gun, and, with no time to extricate it, Colonel

Gainey rushed into Georgetown, with the weapon still conspicuously showing

how close and eager had been the charge, and how narrow the escape. The

wound was not fatal.

On another occasion General Marion

ordered Captain Withers to take Sergeant Macdonald, with four volunteers,

and search out the intentions of the enemy in Georgetown. On the way they

stopped at a wayside house and drank too much brandy. Sergeant Macdonald,

feeling the effects of the potion, with a red face, reined up Selim, and

drawing his claymore, began to pitch and prance about, cutting and

slashing the empty air, and cried out, "Huzza, boys! let’s charge !" Then

clapping spurs to their steeds these six men, huzzaing and flourishing

their swords, charged at full tilt into a town garrisoned by three hundred

British. The enemy supposing this was the advance guard of General Marion,

fled to their redoubts; but all were not fortunate enough to reach that

haven, for several were overtaken and cut down in the streets, among whom

was a sergeant-major, who fell from a back-handed stroke of a claymore

dealt by Sergeant Macdonald. Out of the town the young men galloped

without receiving any injury.

Not long after the above incident,

the sergeant, as usual employing himself in watching the movements of the

British, climbed up into a bushy tree, and thence, with a musket loaded

with pistol bullets, fired at the guard as they passed by; of whom he

killed one man and badly wounded Lieutenant Torquano; then sliding down

the tree, mounted Selim, and was soon out of harm’s way. Repassing the

Black river he left his clothes behind him, which were seized by the

enemy. He sent word to Colonel Watson if he did not immediately send back

his clothes, he would kill eight of his men to compensate for them. He

felt it was a point of honor that he should recover his clothes. Colonel

Watson greatly irritated by a late defeat, was furious at the audacious

message. He contemptuously ordered the messenger to return; but some of

his officers, aware of the character of the sergeant, urged that the

clothes might be returned to the partisan, as he would positively keep his

word. Colonel Watson yielded, and when the messenger returned to the

sergeant, he said, "You may now tell Colonel Watson that I will kill but

four of his men."

The last relation of Sergeant

Macdonald, as given by General Peter Horry, is in reference to Captains

Snipes and McCauley, with the sergeant and forty men, having surprised and

cut to pieces a large party of the enemy near Charleston.

Sergeant Macdonald did not live to

reap the fruit of his labors, or even to see his country free. He was

killed at the siege of Fort Motte, May 12, 1781. In this fort was

stationed a British garrison of one hundred and fifty men under Captain

McPherson, which had been reinforced by a small force of dragoons sent

from Charleston with dispatches for lord Rawdon. General Marion, with the

assistance of Colonel Henry Lee, laid siege to the fortress, which was

compelled to surrender, owing to the burning of the mansion in the center

of the works. Mrs. Rebecca Motte, the lady that owned the mansion,

furnished the bow and arrows used to carry the fire to the roof of the

building. Nathan Savage, a private in the ranks of General Marion’s men,

winged the arrow with the lighted torch. The British did not lose a man,

and General Marion lost two of his bravest,—Lieutenant Cruger and Sergeant

Macdonald. His resting place is unknown. No monument has been erected to

his memory; but his name will endure so long as men shall pay respect to

heroism and devotion to country. |