|

The great Pitt, in his famous eulogy

on the Highland regiments, delivered in 1766, in Parliament, said: "I

sought for merit wherever it could be found. It is my boast that I was the

first minister who looked for it, and found it, in the mountains of the

north. I called it forth, and drew into your service a hardy and intrepid

race of men; men who, when left by your jealousy, became a prey to the

artifices of your enemies, and had gone nigh to have overturned the State,

in the war before the last. These men, in the last war, were brought to

combat on your side; they served with fidelity, as they fought with valor,

and conquered for you in every quarter of the world."

ROYAL HIGHLAND EMIGRANT

REGIMENT.

These same men were destined to be brought from their

homes and help swell the ranks of the oppressors of America. The first

attempt made was to organize the Highland regiments in America. The

MacDonald fiasco in North Carolina and the Highlanders of Sir John Johnson

have already been noticed. But there were other Highlanders throughout the

inhabited districts of America, who had emigrated, or else had belonged to

the 42nd, Fraser’s or Montgomery’s Highlanders. It was desired to collect

these, in so far as it was possible, and organize them into a distinct

regiment. The supervision of this work was given to Colonel Allan MacLean

of Torloisk, Mull, an experienced officer who had seen hard service in

previous wars. The secret instructions given by George III. to William

Tryon, governor of New York, is dated April 3, 1775:

"Whereas an humble application hath been made

to us by Allen McLean Eqre’late Major to our

114th

Regiment, and Lieut-Col: in our Army setting forth, that a considerable

number of our subjects, who have, at different times, emigrated from the

North West parts of North Britain, and have transported themselves, with

their families, to New York, have expressed a desire, to take up Lands

within our said Province, to be held of us, our heirs and successors, in

fee simple; and whereas it may be of public advantage to grant lands in

manner aforesaid to such of the said Emigrants now residing within our

said province as may be desirous of settling together upon some convenient

spot within the same. It is therefore our Will and pleasure, that upon

application to you by the said Allen McLean, and upon his producing to you

an Association of the said Emigrants to the effect of the form hereunto

annexed, subscribed by the heads of the several families of which such

Emigrants shall consist, you do cause a proper spot to be located and

surveyed in one contiguous Tract within our said Province of New York,

sufficient in quantity for the accommodation of such Emigrants, allowing

100 acres to each head of a family, and 500 acres for every other person

of which the said family shall consist; and it is our further will and

pleasure that when the said Lands shall have been located as aforesaid,

you do grant the same by letters patent under the seal of our said

Province unto the said Allen Maclean, in trust, and upon the conditions,

to make allotments thereof in Fee Simple to the heads of Families, whose

names, together with the number of persons in each family, shall have been

delivered in by him as aforesaid, accompanied with the said association,

and it is Our further will and pleasure that it be expressed in the said

letters patent, that the lands so to be granted shall be exempt from the

payment of quit-rents for 20

years from the date thereof, with a

proviso however that all such parts of the said Tracts as shall not be

settled in manner aforesaid within two years from the date of the grant

shall revert to us, and be disposed of in such manner as we shall think

fit; and it is our further will and pleasure, that neither yourself, nor

any other of our Officers, within our said Province, to whose duty it may

appertain to carry these our orders into execution do take any Fee or

reward for the same, and that the expense of surveying and locating any

Tract of Land in the manner and for the purpose above mentioned be

defrayed out of our Revenue of Quit rents and charged to the account

thereof. And we do hereby, declare it to be our further will and pleasure,

that in case the whole or any part of the said Colonists, fit to bear

Arms, shall be hereafter embodied and employed in Our service in America,

either as Commission or non Commissioned Officers or private Men, they

shall respectively receive further grants of Land from us within our said

province, free of all charges, and exempt from the payment of quit rents

for 20 years, in the same proportion to their respective Ranks, as is

directed and prescribed by our Royal Proclamation of the 7th of October

1763. in regard to such officers and soldiers as were employed in our

service during the last War."

This paltry scheme concocted to

raise men for the royal cause could have but very little effect. The

Highlanders, it proposed to reach, were scattered, and the work proposed

must be done secretly and with expedition. To raise the Highlanders

required address, a number of agents, and necessary hardships. Armed with

the warrant Colonel Maclean and some followers proceeded to New York and

from there to Boston, where the object of the visit became known through a

sergeant by name of McDonald who was trying to enlist "men to join the

King’s Troops; they seized him, and on his examination found that he had

been employed by Major Small for this Purpose; they sent him a Prisoner

into Connecticut. This has raised a violent suspicion against the Scots

and Highlanders and will make the execution of Coll Maclean’s Plan more

difficult." [Governor Colderi to Earl of Dartmouth. New York Docs.

Relating to Colonial History, Vol. VIII, p. 588.]

The principal agents engaged with

Colonel Maclean in raising the new regiment were Major John Small and

Captain Alexander McDonald. The latter met with much discouragement and

several escapes. His "Letter-Book" is a mine of information pertaining to

the regiment. As early as November 15, 1775, he draws a gloomy picture of

the straits of the Macdonalds on whom so much was relied by the English

government. "As for all the McDonalds in America they may Curse the day

that was born as being the means of Leading them to ruin from my Zeal and

attachment for government poor Glanaldall I am afraid is Lost as there is

no account of him since a small Schooner Arrived which brought an account

of his having Six & thirty men then and if he should Not be Lost he is

unavoidably ruined in his Means all those up the Mohawk river will be tore

to pieces and those in North Carolina the same so that if Government will

Not Consider them when Matters are Settled I think they are ill treated"

[Letter Book, p. 221.]

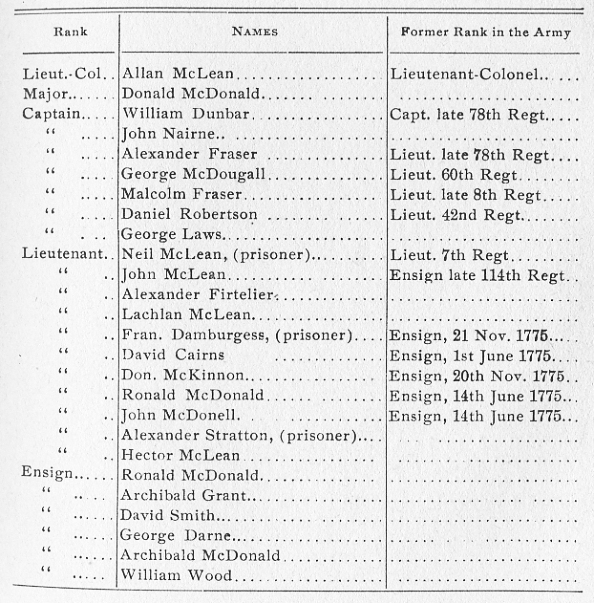

The commissions of Colonel Maclean,

Major John Small and Captain William Dunbar bear date of June 13, 1775,

and all the other captains one day later.

The regiment raised was known as the

Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment and was composed of two battalions, the

first of which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Allan Maclean, and was

composed of Highland emigrants in Canada, and the discharged men of the

42nd, of Fraser’s and Montgomery’s High-landers who had settled in North

America after the peace of 1763. Great difficulty was experienced in

conveying the troops who had been raised in the back settlements to their

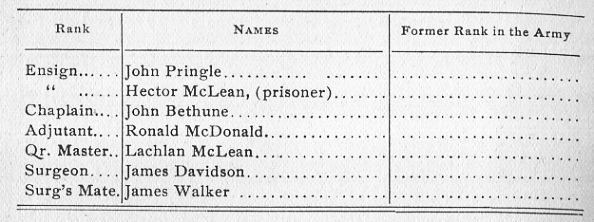

respective destinations. This battalion made the following return of its

officers:

Isle Aux Noix, 15th April, 1778.

The second battalion was commanded

by Major John Small, formerly of the 42nd, and then of the 21st regiment,

which was raised from emigrants arriving in the colonies and discharged

Highland soldiers who had settled in Nova Scotia. Each battalion was to

consist of seven hundred and fifty men, with officers in proportion. In

speaking of the raising of the men Captain Alexander McDonald, in a letter

to General Sir William Howe, under date of Halifax, November 30, 1775,

says:

"Last October was a year when I

found the people of America were determind on Rebellion, I wrote to Major

Small desiring he would acquaint General Gage that I was ready to join the

Army with a hundred as good men as any in America, the General was pleased

to order the Major to write and return his Excellency’s thanks to me for

my Loyalty and spirited offers of Service, but that he had not power at

that time to grant Commissions or raise any troops; however the hint was

improved and A proposal was Sent home to Government to raise five

Companies and I was in the meantime ordered to ingeage as many men as I

possibly Could, Accordingly I Left my own house on Staten Island this same

day year and travelled through frost snow & Ice all the way to the Mohawk

river, where there was two hundred Men of my own Name, who had fled from

the Severity of their Landlords in the Highlands of Scotland, the Leading

men of whom most Chearfully agreed to be ready at a Call, but the affair

was obliged to be kept a profound Secret till it was Known whether the

government approved of the Scheme and otherwise I could have inlisted five

hundred men in a months time, from thence I proceeded straight to Boston

to know for Certain what was done in the affair when General Gage asur’d

me that he had recommended it to the Ministry and did not doubt of its

Meeting with approbation. I Left Boston and went home to my own house and

was ingeaging as Many men as I Could of those that I thought I could

intrust but it was not possible to keep the thing Long a Secret when we

had to make proposals to five hundred men; in the Mean time Coll McLean

arrived with full power from. Government to Collect all the Highlanders

who had Emigrated to America Into one place and to give Every man the

hundred Acres of Land and if need required to give Arms to as many men as

were Capable of bearing them for His Majesty’s Service. Coll McLean and I

Came from New York to Boston to know how Matters would be Settled by Genl

Gage: it was then proposed and Agreed upon to raise twenty Companies or

two Battalions Consisting of one Lt Colonl Commandant two Majors and

Seventeen Captains, of which I was to be the first or oldest Captain and

was confirmed by Coll McLean under his hand Writeing."

At the time of the beginning of

hostilities a large number of Highlanders were on their way from Scotland

to settle in the colonies. In some instances the vessels on which were the

emigrants, were boarded from a man-of-war before their arrival. In some

families there is a tradition that they were captured by a war vessel

Those who did arrive were induced partly by threats and partly by

persuasion to enlist for the war, which they were assured would be of

short duration. These people were not only in poverty, but many were in

debt for their passage, and they were now promised that by enlisting their

debts should be paid, they should have plenty of food as well as full pay

for their services, besides receiving for each head of a family two

hundred acres of land and fifty more for each child, while, in the event

of refusal, there was presented the alternative of going to jail to pay

their debts. The result of the artifices used can be no mystery. Under

such conditions most of the able-bodied men enlisted, in some instances

father and son serving together. Their wives and children were sent to

Halifax, hearing the cannon of Bunker Hill on their passage.

These enlistments formed a part of

the Battalion under Major Small,—five companies of which remained in Nova

Scotia during the war, and the remaining five joining Sir Henry Clinton

and Lord Cornwallis to the southward. That portion of which remained in

Nova Scotia, was stationed at Halifax, Windsor, and Cumberland, and were

distinguished by their uniform good behavior.

The men belonging to the first

battalion were assembled at Quebec. On the approach of the American army

by Lake Champlain, Colonel Maclean was ordered to St. Johns with a party

of militia, but got only as far as St. Denis, where he was deserted by his

men. When Quebec was threatened by the American army under Colonel Arnold,

Colonel Maclean with his regiment consisting of three hundred and fifty

men, was at Sorel, and being forced to decamp from that place, by great

celerity of movement, evaded the army of Colonel Arnold and passed into

Quebec with one hundred of his regiment. He arrived just in time, for the

citizens were about to surrender the city to the Americans. On Colonel

Maclean’s arrival, November 13, 1775, the garrison consisted only of fifty

men of the Fusiliers and seven hundred militia and seamen. There had also

just landed one hundred recruits of Colonel Maclean’s corps from

Newfoundland, which had been raised by Malcolm Fraser and Captain

Campbell. Also, at the same time, there arrived the frigate Lizard, with

£20,000 cash, all of which put new spirits into the garrison. The arrival

of the veteran Maclean greatly diminished the chances of Colonel Arnold.

Colonel Maclean now bent his energies towards saving the town;

strengthened every point; enthused the lukewarm, and by emulation kept up

a good spirit among them all. When General Carleton, leaving his army

behind him, arrived in Quebec he found that Colonel Maclean had not only

withstood the assaults of the Americans but had brought order and system

out of chaos. In the final assault on the last day of the year, when the

brave General Montgomery fell, the Highlanders were in the midst of the

fray.

Many of the Americans were captured

at this storming of Quebec. One of them narrates that "January 4th, on the

next day, we were visited by Colonel Maclean, an old man, attended by

other officers, for a peculiar purpose, that is, to ascertain who among us

were born in Europe. We had many Irishmen and some Englishmen. The

question was put to each; those who admitted a British birth, were told

they must serve his majesty in Colonel Maclean’s regiment, a new corps,

called the emigrants. Our poor fellows, under the fearful penalty of being

carried to Britain, there to be tried for treason, were compelled by

necessity, and many of them did enlist." [Henry's Campaign Against Quebec,

1775, p. 136.]

Such men could hardly prove to be

reliable, and it can be no astonishment to read what Major Henry Caldwell,

one of the defenders of Quebec says of it:

"Of the prisoners we took, about 100

of them were Europeans, chiefly from Ireland; the greatest part of them

engaged voluntarily in Col. McLean’s corps, but about a dozen of them

deserting in the course of a month, the rest were again confined, and not

released till the arrival of the Isis, when they were again taken into the

corps." [Invasion of Canada 1775, p. 14.]

Colonel Arnold despairing of

capturing the town by assault, established himself on the Heights of

Abraham, with the intention of cutting off supplies and blockading the

town. In this situation he reduced the garrison to great straits, all

communication with the country being cut off. He erected batteries and

made several attempts to get possession of the lower town, but was foiled

at every point by the vigilance of Colonel Maclean. On the approach of

spring, Colonel Arnold, despairing of success, raised the siege.

The battalion remained in the

province of Canada during the war, and was principally employed in small,

but harrassing enterprises. In one of these, Captain Daniel Robertson,

Lieutenant Hector Maclean, and Ensign Archibald Grant, with the grenadier

company, marched twenty days through the woods with no other direction

than the compass, and an Indian guide. The object being to surprise a

small post in the interior, which was successful and attained without

loss. By long practice in the woods the men had become very intelligent

and expert in this kind of warfare.

The reason why this regiment was not

with the army of General Burgoyne, and thus escaped the humiliation of the

surrender at Saratoga, has been stated by that officer in the following

language: that he proposed to leave in Canada "Maclean’s Corps, because I

very much apprehend desertions from such parts of it as are composed of

Americans, should they come near the enemy. In Canada, whatsoever may be

their disposition, it is not so easy to effect it." [State of the

Expedition, p. VI.]

Notwithstanding the conduct of

Colonel Allan Maclean at the siege of Quebec and his great zeal in behalf

of Britain his corps was not yet recognized, though he had at the outset

been promised establishment and rank for it. He therefore returned to

England where he arrived on September 1, 1776, to seek justice for himself

and men. They were not received until the close of 1778, when the regiment

was numbered the 84th, at which time Sir Henry Clinton was appointed its

Colonel, and the battalions ordered to be augmented to one thousand men

each. The uniform was the full Highland garb, with purses made of

raccoons’ instead of badger’s skins. The officers wore the broad sword and

dirk, and the men a half basket sword.

"On a St. Andrew’s day a ball was

given by the officers of the garrison in which they were quartered to the

ladies in the vicinity. When one of the ladies entered the ball-room, and

saw officers in the Highland dress, her sensitive delicacy revolted at

what she though an indecency, declaring she would quit the room if these

were to be her company. This occasioned some little embarrassment. An

Indian lady, sister of the Chief Joseph Brant, who was present with her

daughters, observing the bustle, inquired what was the matter, and being

informed, she cried out, ‘This must be a very indelicate lady to think of

such a thing; she shows her own arms and elbows to all the men, and she

pretends she cannot look at these officers’ bear legs, although she will

look at my husband’s bare thighs for hours together; she must think of

other things, or she would see no more shame in a man showing his legs,

than she does in showing her neck and breast.’ These remarks turned the

laugh against the lady’s squeamish delicacy, and the ball was permitted to

Proceed without the officers being obliged to retire." [Stewart’s Sketches

of the Highlanders, Vol. II, p. 186.]

With every opportunity offered the

first battalion to desert, in consequence of offers of land and other

inducements held out by the Americans, not one native Highlander deserted

and only one Highlander was brought to the halberts during the time they

were embodied.

The history of the formation of the

two battalions is dissimilar: that of the second was not attended with so

great difficulties. In the formation of the first all manner of devices

were entered into, and various disguises were resorted to in order to

escape detection. Even this did not always protect them.

"It is beyond the power of

Expression to give an Idea of the expence & trouble our Officers have

Undergone in these expeditions into the Rebellious provinces. Some of them

have been fortunate enough to get off Undiscovered—But Many have been

taken abused by Mobs in an Outragious manner & cast into prisons with

felons, where they have Suffered all the Evils that revengeful Rage

ignorance Bigotry & Inhumanity could inflict— There has been even

Skirmishes on such Occasions.*****It was an uncommon Exertion in one of

our Offrs. to make his Escape with forty highlanders from the Mohawk river

to Montreal havg. had nothing to eat for ten days but their Dogs & herbs &

in another to have on his private Credit & indeed ruin, Victualled a

Considerable Number of Soldiers he had engaged in hopes of getting off

with them to Canada, but being at last taken & kept in hard imprisonmt for

near a year by the Rebels to have effected his escape & Collecting his

hundred men to have brot them thro’ the Woods lately from near Abany to

Canada." [LetterBook, p. 856.]

Difficulties in the formation of the

regiment and placing it on the establishment grew out of the opposition of

Governor Legge, and from him, through General Gage transmitted to the

ministry, when all enlistments, for the time being were prohibited. The

officers, from the start had been assured that the regiment should be

placed on the establishment, and each should be entitled to his rank and

in case of reduction should go on half pay. The officers should consist of

those on half pay who had served in the last war, and had settled in

America. When the regiment had been established and numbered, through the

exertions of Colonel Maclean the ranks were rapidly filled, and the

previous difficulties overcome.

The winter of 1775-1776, was very

severe on the second battalion. Although stationed in Halifax they were

without sufficient clothing or proper food, or pay, and the officer in

charge—. Captain Alexander McDonald—without authority to draw money, or a

regular warrant to receive it. In January "the men were almost stark naked

for want of clothing," and even barefooted. The plaids and Kilmarnocks

could not be had. As late as March 1st there was "not a shoe nor a bit of

leather to be had in Halifax for either love or money," and men were

suffering from their frosted feet. "The men made a horrid and scandalous

appearance on duty, insulted and despised by the soldiers of the other

corps." In April 1778, clothing that was designed for the first battalion,

having been consigned to Halifax, was taken by Captain McDonald and

distributed to the men of the second. Out of this grew an acrimonious

correspondence. Of the food, Captain McDonald writes:

"We are served Served Since prior to

September last with Flower that is Rank poison at lest Bread made of Such

flower— The Men of our Regiment that are in Command at the East Battery

brought me a Sample of the fflower they received for a Months provision,

it was exactly like Chalk & as Sower as Vinegarr I asked the Doctors

opinion of it who told me it was Sufficient to Destroy all the Regiment to

eatt Bread made of Such fflower; it is hard when Mens Lives are So

precious and so much wanted for the Service of their King and country,

that they Should thus wantonly be Sported with to put money in the pocket

of any individuall."

It appears to have been the policy

to break up the second battalion and have it serve on detached duty. Hence

a detachment was sent to Newfoundland, another to Annapolis, at

Cumberland, Fort Howe, Fort Edward, Fort Sackville and Windsor, but

rallying at Halifax as the headquarters—to say nothing of those sent to

the Southern States. No wonder Captain McDonald complains, "We have

absolutely been worse used than any one Regiment in America and has done

more duty and Drudgery of all kinds than any other Bn. in America these

thre Years past and it is but reasonable Just and Equitable that we should

now be Suffered to Join together at least as early as possible in the

Spring and let some Other Regimt relieve the difft. posts we at present

Occupy."

But it was not all garrison duty.

Writing from Halifax, under date of July 13th, 1777, Captain McDonald

says:

"Another Attempt has been made from

New England to invade this province wch. is also defeated by a detachmt

from our Regt & the Marines on board of Captn Hawker. Our Detachmt went on

board of him here & he having a Quick passage to the River St John’s wch.

divides Nova Scotia from New England & where the Rebells were going to

take post & Rebuild the old fort that was there the last War. Immediately

on Captn Hawker’s Arrival there Our men under the Commd. of Ensn. Jno

McDonald & the Marines under that of a Lieut were landed & Engaged the

Enemy who were abt. a hundred Strong & after a Smart firing & some killed

& wounded on both Sides the Rebells ran with the greatest precipitation &

Confusion to their boats. Some of our light Armed vessells pursued them &

I hope before this time they are either taken or starving in the Woods."

Whatever may be said of the good

behavior of the men of the second battalion, there were three at least

whom Captain McDonaid describes as "rascales." He also gives the following

severe rebuke to one of the officers:

"Halifax 16th Febry 1777

Mr. Jas. McDonald.

I am sorry to inform you that every

Accot I receive from Windsor is very unfavorable in regard to you. Your

Cursed Carelessness & slovenlyness about your own Body and your dress

Nothing going on but drinking Calybogus Schewing Tobacco & playing Cards

in Place of that decentness & Cleanliness that all Gentlemen who has the

least Regard for themselves & Character must & does observe. I am afraid

from your Conduct that you will be no Credit or honor to the Memories of

those Worthies from whom you are descended & if you have no regard for

them or your self I need not expect you’ll be at any pains to be of Any

Credit to me for anything I can do for you. I am about Giving you Rank

agreeable to Col. McLean’s plan & on Accot. of your having bro’t more men

to the Regimt. than either Mr. Fitz Gerd. or Campbell You are to be the

Second in Command at that post Lt. Fitz Ger’d. the third & Campbell the

fourth. And I hope I shall never have Occasion to write to you in this

Manner again. I beg you will begin now to mend your hand to write & learn

to keep Accots. that you may be able to do Some thing like an officer if

ever you expect to make a figure in the Army You must Change your plan &

lay yr. money out to Acquire such Accomplishm’ts. befitting an officer

rather than Tobacco, Calybogus and the Devil knows what. I am tired of

Scolding of you, so will say no more."

But little has been recorded of the

five companies of the second battalion that joined Sir Henry Clinton and

lord Cornwallis. The company called grenadiers was in the battle of Eutaw

Springs, South Carolina, fought September 8, 1781. This was one of the

most closely contested battles of the Revolution, in which the grenadier

company was in the thickest and severest of the fight. The British army,

under Colonel Alexander Stuart, of the 3rd regiment was drawn up in a line

extending from Eutaw creek to an eighth of a mile southward. The Irish

Buffs (third regiment) formed the right; Lieutenant Colonel Cruger’s

Loyalists the center; and the 63rd and 64th regiments the left. Near the

creek was a flank battalion of infantry and the grenadiers, under

Major Majoribanks, partially covered and concealed by a thicket on the

bank of the stream. The Americans, under General Greene, having routed two

advanced detachments, fell with great spirit on the main body. After the

battle had been stubbornly contested for some time, Major Majoribank’s

command was ordered up, and terribly galled the American flanks. In

attempting to dislodge them, the Americans received a terrible volley from

behind the thicket. Soon the entire British line fell back, Major

Majoribanks covering the movement. They abandoned their camp, destroyed

their stores and many fled precipitately towards Charleston, while Major

Majoribanks halted behind the palisades of a brick house. The American

soldiers, in spite of the orders of General Greene and the efforts of

their officers began to pillage the camp, instead of attempting to

dislodge Major Majoribanks. A heavy fire was poured upon the Americans who

were in the British camp, from the force that had taken refuge in the

brick house, while Major Majoribanks moved from his covert on the

right. The light horse or legion of

Colonel Henry Lee, remaining under the control of that officer, followed

so closely upon those who, had fled to the house that the fugitives in

closing the doors shut out two or three of their own officers. Those of

the legion who had followed to the door seized each a prisoner, and

interposing him as a shield retreated beyond the fire from the windows.

Among those captured was Captain Barre, a brother of the celebrated

Colonel Barre of the British parliament, having been seized by Captain

Manning. In the terror of the moment Barre began to recite solemnly his

titles: "I am Sir Henry Barre deputy adjutant general of the British army,

captain of the 52d regiment, secretary of the commandant at Charleston—"

Are you indeed ?" interrupted Captain Manning; "you are my prisoner now,

and the very man I was looking for; come along with me." He then placed

his titled prisoner between him and the fire of the enemy, and retreated.

The arrest of the Americans by Major

Majoribanks and the party that had fled into the brick house, gave Colonel

Stuart an opportunity to rally his forces, and while advancing, Major

Majoribanks poured a murderous fire into the legion of Colonel Lee, which

threw them into confusion. Perceiving this, he sallied out seized the two

field pieces and ran them under the windows of the house. Owing to the

crippled condition of his army, and the shattering of his cavalry by the

force of Major Majoribanks, General Greene ordered a retreat, after a

conflict of four hours. The British repossessed the camp, but on the

following day decamped, abandoning seventy-two of their wounded.

Considering the numbers engaged, both parties lost heavily. The Americans

had one hundred and thirty rank and file killed, three hundred and

eighty-five wounded, and forty missing. The loss of the British, according

to their own report, was six hundred and ninety-three men, of whom

eighty-five were killed.

At the conclusion of the war the

transports bearing the companies were ordered to Halifax, where the men

were discharged; but, owing to the violence of the weather, and a

consequent loss of reckoning, they made the island of Nevis and St. Kitt’s

instead of Halifax. This delayed the final reduction till 1784. In the

distant quarters of the first battalion, they were forgotten. By their

agreement they should have been discharged in April 1783, but orders were

not sent until July 1784.

It is possible that a roll of the

officers of the second battalion may be in existence. The following names

of the officers are preserved in McDonald’s "Letter-Book":

Major John Small, commandant:

Captains Alexander McDonald, Duncan Campbell. Ronald McKinnon, Murdoch

McLean, Alexander Campbell, John McDonald and Allan McDonaid; Lieutenants

Gerald Fitzgerald, Robert Campbell. James McDonald and Lachlan McLean;

Ensign John Day chaplain, Doctor Boynton.

The uniform of the Royal Highland

Emigrant regiment was the full Highland garb, with purses made of

raccoon’s instead of badger’s skins. The officers wore the broad sword and

dirk, and the men a half basket sword, as previously stated.

At the conclusion of the war grants

of land were given to the officers and men, in the proportion of five

thousand acres to a field officer, three thousand to a captain, five

hundred to a subaltern, two hundred to a serjeant and one hundred to each

soldier. All those who had settled in America previous to the war,

remained, and took possession of their lands, but many of the others

returned to Scotland. The men of Major Small’s battalion went to Nova

Scotia, where they settled a township, and gave it the name of Douglas, in

Hants County; but a number settled on East River.

The first to come to East River. of

the 84th, was big James Fraser, in company with Donald McKay and fifteen

of his comrades, and took up a tract of three thousand four hundred acres

extending along both sides of the river. Their discharges are dated April

10, 1784, but the grant November 3, 1785. About the same time of the

occupation of the East River, in Picton County, the West Branch was

occupied by men of the same regiment; the first of whom were David McLean

and John Fraser.

The settlers of East Branch, or

River, of the 84th, on the East side were Donald Cameron, a native of

Urquhart, Scotland; served eight years; possessed one hundred and fifty

acres; his son Duncan served two years as a drummer boy in the regiment.

Alexander Cameron, one hundred acres. Robert Clark, one hundred acres.

Finlay Cameron, four hundred. Samuel Cameron, one hundred acres. James

Fraser, a native of Strathglass, three hundred and fifty acres. Peter

Grant, James McDonald, Hugh McDonald, one hundred acres.

On the west side of same river:

James Fraser, one hundred acres. Duncan McDonald, one hundred acres. John

McDonald, two hundred and fifty acres. Samuel Cameron, three hundred

acres. John Chisholm, sen., three hundred acres. John Chisholm, jun., two

hundred acres. John McDonald, two hundred and fifty acres.

Those who settled at West Branch and

other places on East River were, William Fraser, from Inverness, three

hundred and fifty acres. John McKay. three hundred acres. John Robertson,

four hundred and fifty. William Robertson, two hundred acres. John

Fraser, from Inverness, three hundred acres. Thomas Fraser, from

Inverness, two hundred acres. Thomas McKinzie, one hundred acres. David

McLean, a sergeant in the army, five hundred acres. Alexander Cameron,

three hundred acres. Hector McLean, four hundred acres. John Forbes, from

Inverness, four hundred acres. Alexander McLean, five hundred acres.

Thomas Fraser, Jun., one hundred acres. James McLellan, from Inverness,

five hundred acres. Donald Chisholm, from Strathglass, three hundred and

fifty acres. Robert Dundas (four hundred and fifty acres), Alexander

Dunbar (two hundred acres), and William Dunbar, (three hundred acres), all

three brothers, from Inverness, and of the 84th regiment. James Cameron,

84th regiment, three hundred acres. John McDougall, two hundred and fifty

acres. John Chisholm, three hundred acres. Donald Chisholm, Jun., from

Inverness, four hundred acres. Robert Clark, 84th, one hundred acres.

Donald Shaw, from Inverness, three hundred acres. Alexander McIntosh, from

Inverness, five hundred acres, and John McLellan, from Inverness, one

hundred acres. Of the grantees of the West Branch, those designated from

Inverness, were from the parish of Urquhart and served in the 84th, as did

also those so specified. It is more than probable that all the others were

not in the Royal Highland Emigrant regiment, or even served in the war.

The members of the first, or Colonel

MacLean’s battalion settled in Canada, many of whom at Montreal, where

they rallied around their chaplain, John Bethune. This gentleman acted as

chaplain of the Highlanders in North Carolina, and was taken prisoner at

the battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge. After remaining a prisoner for about a

year, he was released, and made his way to Nova Scotia and for some time

resided at Halifax. He received the appointment of chaplain in the Royal

Highland Emigrant regiment. He received a grant of three thousand acres,

located in Glengarry, and having a growing family to provide for, each of

whom was entitled to two hundred acres, he removed to Williamstown, then

the principal settlement in Glengarry. Besides his allotment of land, he

retired from the army on half pay. In his new home he ever maintained an

honorable life.

FORTY-SECOND OR ROYAL HIGHLAND

REGIMENT.

The 42nd or Black Watch, or Royal

Highlanders, left America in 1767, and sailed direct for Cork, Ireland. In

1775 the regiment embarked at Donaghadee, and landed at Port Patrick,

after an absence of thirty-two years from Scotland. From Port Patrick it

marched to Glasgow. Shortly after its arrival in Glasgow two companies

were added, and all the companies were augmented to one hundred rank and

file, and when completed numbered one thousand and seventy-five men,

including serjeants and drummers.

Hitherto the officers had been

entirely Highlanders and Scotch. Contrary to the remonstrances of lord

John Murray, the lord lieutenant of Ireland succeeded in admitting three

English officers into the regiment, Lieutenants Crammond, Littleton, and

Franklin, thus cancelling the commissions of Lieutenants Grant and

Mackenzie. Of the soldiers nine hundred and thirty-one were Highlanders,

seventy-four Lowland Scotch, five English, one Welsh and two Irish.

On account of the breaking out of

hostilities the regiment was ordered to embark for America. The recruits

were instructed in the use of the firelock, and, from the shortness of the

time allowed, were even drilled by candle-light. New arms and

accoutrements were supplied to the men, and the Colonel, at his own

expense, furnished them with broad swords and pistols.

April 14, 1776, the Royal

Highlanders, in conjunction with Fraser’s Highlanders, embarked at

Greenock to join an expedition under General Howe against the Americans.

After some delay, both regiments sailed on May 1st under the convoy of the

Flora, of thirty-two guns, and a fleet of thirty-two ships, the Royal

Highlanders being commanded by Colonel Thomas Stirling of Ardoch. Four

days after they had sailed, the transports separated in a gale of wind.

Some of the scattered transports of both regiments fell in with General

Howe’s army on their voyage from Halifax; and others, having received

information of this movement, followed the main body and joined the army

at Staten Island.

When Washington took possession of

Dorchester heights, on the night of March 4, 1776, the situation of

General Howe, in Boston, became critical, and he was forced to evacuate

the city with precipitation. He left no cruisers in Boston bay to warn

expected ships from England that the city was no longer in his possession.

This was very fortunate for the Americans, for a few days later several

store-ships sailed into the harbor and were captured. The Scotch fleet

also headed that way, and some of the transports, not having received

warning, were also taken in the harbor, but principally of Fraser’s

Highlanders. By the last of June, about seven hundred and fifty

Highlanders belonging to the Scotch fleet, were prisoners in the hands of

the Americans.

The Royal Highlanders lost but one

of their transports, the Oxford, and at the same time another transport in

company with her, having on board recruits for Fraser’s Highlanders, in

all two hundred and twenty men. They were made prizes of by the Congress

privateer, and all the officers, arms and ammunition were taken from the

Oxford, and all the soldiers were placed on board that vessel with a prize

crew of ten men to carry her into port. In a gale of wind the vessels

became separated, and then the carpenter of the Oxford formed a party and

retook her, and sailed for the Chesapeake. On June 20th, they sighted

Commodore James Barron’s vessel, and dispatched a boat with a sergeant,

one private and one of the men who were put on board by the Congress to

make inquiry. The latter finding a convenient opportunity, informed

Commodore Barron of their situation, upon which he boarded and took

possession of the Oxford, and brought her to Jamestown. The men were

marched to Williamsburgh, Virginia, where every inducement was held out to

them to join the American cause. When the promise of military promotion

failed to have an effect, they were then informed that they would have

grants of fertile land, upon which they could live in happiness and

freedom. They declared they would take no land save what they deserved by

supporting the king. They were then separated into small parties and sent

into the back settlements; and were not exchanged until 1778, when they

rejoined their regiments.

Before General Sir William Howe’s

army arrived, or even any vessels of his fleet, the transport Crawford

touched at Long Island. Under date of June 24, 1776, General Greene

notified Washington that "the Scotch prisoners, with their baggage, have

arrived at my Quarters." The list of prisoners are thus given: "Forty

second or Royal Highland Regiment: Captain John Smith and Lieutenant

Robert Franklin. Seventy-first Regiment: Captain Norman McLeod and lady

and maid; Lieutenant Roder- ick McLeod; Ensign Colin Campbell and lady;

Surgeon’s Mate, Robert Boyce; John McAlister, Master of the Crawford

transport; Norman McCullock, a passenger; two boys, servants; McDonald,

servant to Robert Boyce; Shaw, servant to Captain McLeod. Three boys,

servants, came over in the evening." [Am. Archives, Fourth Series, Vol.

VI, p. 1055.]

General Howe, on board the frigate

Greyhound, arrived in the Narrows, from Halifax, on June 25th,

accompanied by two other ships-of-war. He came in advance of the fleet

that bore his army, in order to consult with Governor Tryon and ascertain

the position of affairs at New York. For three or four days after his

arrival armed vessels kept coming, and on the twenty-ninth the main body

of the fleet arrived, and the troops were immediately landed on Staten

Island. General Howe was soon after reinforced by English regulars and

German mercenaries, and at about the same time Sir Henry Clinton and

Admiral Parker, with their broken forces came from the south and joined

them. Before the middle of August all the British reinforcements had

arrived at Staten Island and General Howe’s army was raised to a force of

thirty thousand men. On August 22nd, a large body of troops, under

cover of the guns of the Rainbow, landed upon Long Island. Soon after five

thousand British and Hessian troops poured over the sides of the English

ships and transports and in small boats and galleys were rowed to the Long

Island shore, covered by the guns of the Phoenix, Rose and Greyhound. The

invading force on Long Island numbered fifteen thousand, well armed and

equipped, and having forty heavy cannon.

The three Highland battalions were

first landed on Staten island, and immediately a grenadier battalion was

formed by Maor Charles Stuart. The staff appointments were taken from the

Royal Highlanders. The three light companies also formed a battalion in

the brigade under Lieutenant-Colonel Abercromby. The grenadiers were

remarkable for strength and height, and considered equal to any company in

the army. The eight battalion companies were formed into two temporary

battalions, the command of one was given to Major William Murray, and that

of the other to Major William Grant. These small battalions were brigaded

under Sir William Erskine, and placed in the reserve, with the grenadiers

and light infantry of the army, under command of lord Cornwallis.

Lieutenant—Colonel Stirling, from

the moment of landing, was active in drilling the 42d in the methods of

fighting practiced in the French and Indian war, in which he was well

versed. The Highlanders made rapid progress in this discipline, being, in

general, excellent marksmen.

It was about this time that the

broadswords and pistols received at Glasgow were laid aside. The pistols

were considered unnecessary, except in the field. The broadswords retarded

the men when marching by getting entangled in the brushwood.

The reserve of Howe’s army was

landed first at Gravesend Bay, and being moved immediatelv forward to Flat

Bush, the Highlanders and a corps of Hessians were detached to a little

distance, where they encamped. The whole army encamped in front of the

villages of Gravesend and Utrecht. A woody range of hills, which

intersected the country from east to west, divided the opposing armies.

General Howe resolved to bring on a

general action and make the attack in three divisions. The right wing

under General Clinton seized, on the night of August 26th, a pass on the

heights, about three miles from Bedford. The main body pushed into the

level country which lay between the hills and the lines of General Israel

Putnam. Whilst these movements were in process, Major-General Grant of

Ballindalloch, with his brigade, supported by the Royal Highlanders from

the reserve, was directed to march from the left along the coast to the

Narrows, and make an attack in that quarter. At nine o’clock, on the

morning of the 22nd, the right wing having reached Bedford, attacked the

left of the American army, which, after a short resistance, quitted the

woody grounds, and in confusion retired to their lines, pursued by the

British troops, Colonel Stuart leading with his battalion of Highland

grenadiers. When the firing at Bedford was heard at Flat Bush, the

Hessians advanced, and, attacking the center of the American army, drove

them through the woods, capturing three cannon. Previously, General Grant,

with the left of the army, commenced the attack with a cannonade against

the Americans under lord Stirling. The object of lord Stirling was to

defend the pass and keep General Grant in check. He was in the British

parliament when Grant made his speech against the Americans, and

addressing his soldiers said, in allusion to the boasting Grant that he

would "undertake to march from one end of the continent to the other, with

five thousand men." "He may have his five thousand men with him now—we are

not so many—but I think we are enough to prevent his advancing further on

his march over the continent, than that mill-pond," pointing to the head

of Gowanus bay. This little speech had a powerful effect, and in the

action showed how keenly they felt the insult. General Grant had been

instructed not to press an attack until informed by signal-guns from the

right wing. These signals were not given until eleven o’clock, at which

time lord Stirling was hemmed in. When the truth flashed upon him he

hurled a few of his men against lord Cornwallis, in order to keep him at

bay while a part of his army might escape. Lord Cornwallis yielded, and

when on the point of retreating received large reinforcements which turned

the fortunes of the day against the Americans. General Grant drove the

remains of lord Stirling’s army before him, which escaped across Gowanus

creek, by wading and swimming.

The victorious troops, made hot and

sanguinary by the fatigues and triumphs of the morning, rushed upon the

American lines, eager to carry them by storm. But the day was not wholly

lost. Behind the entrechments were three thousand determined men who met

the advancing British army by a severe cannonade and volleys of musketry.

Preferring to win the remainder of the conquest with less bloodshed,

General Howe called back his troops to a secure place in front of the

American lines, beyond musket shot, and encamped for the night.

During the action Washington

hastened over from New York to Brooklyn and galloped up to the works. He

arrived there in time to witness the catastrophe. All night he was engaged

in strengthening his position; and troops were ordered from New York. When

the morning dawned heavy masses of vapor rolled in from the sea. At ten

o’clock the British opened a cannonade on the American works, with

frequent skirmishes throughout the day. Rain fell copiously all the

afternoon and the main body of the British kept their tents, but when the

storm abated towards evening, they commenced regular approaches within

five hundred yards of the American works. That night Washington drew off

his army of nine thousand men, with their munitions of war, transported

them over a broad ferry to New York, using such consummate skill that the

British were not aware of his intention until next morning, when the last

boats of the rear guard were seen out of danger.

The American loss in the battle of

Long Island did not exceed sixteen hundred and fifty, of whom eleven

hundred were prisoners General Howe stated his own loss to have been, in

killed, wounded, and prisoners, three hundred and sixty-seven. The loss of

the Highlanders was, Lieutenant Crammond and nine rank and file wounded,

of the 42d; and three rank and filed killed, and two sergeants and nine

rank and file wounded, of the 71st regiment.

In a letter to lord George Germaine,

under date of September 4, 1776, lord Dunmore says:

I was with the Highlanders and

Hessians the whole day, and it is with the utmost pleasure I can assure

your lordship that the ardour of both these corps on that day must have

exceeded his Majesty’s most sanguine wish."

Active operations were not resumed

until September 15th, when the British reserve, which the Royal

Highlanders had rejoined after the action at Brooklyn, crossed the river

in flat boats from Newtown creek, and landed at Kip’s bay covered by a

severe cannonade from the ships-of-war, whose guns played briskly upon the

American batteries. Washington, hearing the firing, rode with speed

towards the scene of action. To him a most alarming spectacle was

presented. The militia had fled, and the Connecticut troops had caught the

panic, and ran without firing a gun, when only fifty of the British had

landed. Meeting the fugitives he used every endeavor to stop their flight.

In vain their generals tried to rally them; but they continued to flee in

the greatest confusion, leaving Washington alone within eighty yards of

the foe. So incensed was he at their conduct that he cast his chapeau to

the ground, snapped his pistols at several of the fugitives, and

threatened others with his sword. So utterly unconscious was he of danger,

that he probably would have fallen had not his attendants seized the

bridle of his horse and hurried him away to a place of safety. Immediately

he took measures to protect his imperilled army. He retreated to Harlem

heights, and sent an order to General Putnam to evacuate the city

instantly. This was fortunately accomplished, through the connivance of

Mrs. Robert Murray. General Sir William Howe, instead of pushing forward

and capturing the four thousand troops under General Putnam, immediately

took up his quarters with his general officers at the mansion of Robert

Murray, and sat down for refreshments and rest. Mrs. Murray knowing the

value of time to the veteran Putnam, now in jeopardy, used all her art to

detain her uninvited guests. With smiles and pleasant conversation, and a

profusion of cakes and wine, she regaled them for almost two hours.

General Putnam meanwhile receiving his orders, immed— iately obeyed, and a

greater portion of his troops, concealed by the woods, escaped along the

Bloomingdale road, and before being discovered had passed the encampment

upon the Ineleberg. The rear-guard was attacked by the Highlanders and

Hessians, just as a heavy rain began to fall; and the drenched army, after

losing fifteen men killed, and three hundred made prisoners, reached

Harlem heights.

"This night Major Murray was nearly

carried off by the enemy, but saved himself by his strength of arm and

presence of mind. As he was crossing to his regiment from the battalion

which he commanded, he was attacked by an American officer and two

soldiers, against whom he defended himself for some time with his fusil,

keeping them at a respectful distance. At last, however, they closed upon

him, when unluckily his dirk slipped behind, and he could not, owing to

his corpulence, reach it. Observing that the rebel (American) officer had

a sword in his hand, he snatched it from him, and made so good use of it,

that he compelled them to fly, before some men of the regiment, who had

heard the noise, could come up to his assistance. He wore the sword as a

trophy during the campaign." [Stewart's Sketches, Vol. I, p. 360.]

On the 16th the light infantry was

sent out to dislodge a party of Americans who had taken possession of a

wood facing the left of the British. Adjutant-General Reed brought

information to Washington that the British General Leslie was pushing

forward and had attacked Colonel Knowlton and his rangers. Colonel

Knowlton retreated, and the British appeared in full view and sounded

their bugles. Washington ordered three companies of Colonel Weedon’s

Virginia regiment, under Major Leitch, to join Knowlton's rangers, and

gain the British rear, while a feigned attack should be made in front. The

vigilant General Leslie perceived this, and made a rapid movement to gain

an advantageous position upon Harlem plains, where he was attacked upon

the flank by Knowlton and Leitch. A part of Leslie’s force, consisting of

Highlanders, that had been concealed upon the wooded hills, now came down,

and the entire British body changing front, fell upon the Americans with

vigor. A short but severe conflict ensued. Major Leitch, pierced by three

balls, was borne from the field, and soon after Colonel Knowlton was

brought to the ground by a musket ball. Their men fought on bravely,

contesting every foot of the ground, as they fell back towards the

American camp. Being reinforced by a part of the Maryland regiments of

Griffiths and Richardson, the tide of battle changed. The British were

driven back across the plain, hotly pursued by the Americans, till

Washington, fearing an ambush, ordered a retreat.

In the battle of Harlem the British

loss was fourteen killed, and fifty officers and seventy men wounded. The

42nd, or Royal Highlanders lost one sergeant and three privates killed,

and Captains Duncan Macpherson and John Mackintosh, Ensign Alexander

Mackenzie (who died of his wounds), and three sergeants, one piper, two

drummers, and forty-seven privates wounded.

This engagement caused a temporary

pause in the movements of the British, which gave Washington an

opportunity to strengthen both his camp and army. The respite was not of

long duration for on October 12th, General Howe embarked his army in

flat-bottomed boats, and on the evening of the same day landed at

Frogsneck, near Westchester; but on the next day he re-embarked his troops

and landed at Fell’s Point, at the mouth of the Hudson. On the 14th he

reached the White Plains in front of Washington’s position. General Howe’s

next determination was to capture Fort Washington, which cut off the

communication between New York and the continent, to the eastward and

northward of Hudson river, and prevented supplies being sent him by way of

Kings-bridge. The garrison consisted of over two thousand men under

Colonel Magaw. A deserter informed General Howe of the real condition of

the garrison and the works on Harlem Heights. General Howe was agreeably

surprised by the information, and immediately summoned Colonel Magaw to

surrender within an hour, intimating that a refusal might subject the

garrison to massacre. Promptly refusing compliance, he further added: "I

rather think it a mistake than a settled resolution in General Howe, to

act a part so unworthy of himself and the Dritish nation." On November

16th the Hessians, under General Knyphausen, supported by the whole of the

reserve under earl Percy, with the exception of the 42nd, who were to make

a feint on the east side of the fort, were to make the principal attack.

Before daylight the Royal Highlanders embarked in boats, and landed in a

small creek at the foot of the rock, in the face of a severe fire.

Although the Highlanders had discharged the duties which had been assigned

them, still determined to have a full share in the honors of the day,

resolved upon an assault, and assisted by each other, and by the brushwood

and shrubs which grew out of the crevices of the rocks, scrambled up the

precipice. On gaining the summit, they rushed forward, and drove back the

Americans with such rapidity, that upwards of two hundred, who had no time

to escape, threw down their arms. Pursuing their advantage, the

Highlanders penetrated across the table of the hill, and met lord Percy as

he was coming up on the other side. By turning their feint into an

assault, the Highlanders facilitated the success of the day. The result

was that the Americans surrendered at discretion. They lost in killed and

wounded one hundred and about twenty-seven hundred prisoners. The loss of

the British was twenty killed and one hundred and one wounded; that of the

Royal Highlanders being one sergeant and ten privates killed, and

Lieutenants Patrick Graeme, Norman Macleod, and Alexander Grant, and for

sergeants and sixty-six rank and file, wounded.

The hill, up which the Highlanders

charged, was so steep, that the ball which wounded Lieutenant Macleod,

entering the posterior part of his neck, ran down on the outside of his

ribs, and lodged in the lower part of his back. One of the pipers, who

began to play when he reached the point of a rock on the summit of the

hill, was immediately shot, and tumbled from one piece of rock to another

till he reached the bottom. Major Murray, being a large and corpulent man,

could not attempt the steep assent without assistance. The soldiers eager

to get to the point of duty, scrambled up, forgetting the position of

Major Murray, when he, in a supplicating tone cried, "Oh soldiers, will

you leave me !" A party leaped down instantly and brought him up,

supporting him from one ledge of rocks to another till they got him to the

top.

The next object of General Howe was

to possess Fort Lee. Lord Cornwallis, with the grenadiers, light infantry,

33rd regiment and Royal Highlanders, was ordered to attack this post. But

on their approach the fort was hastily abandoned. Lord Cornwallis,

re-enforced by the two battalions of Fraser’s Highlanders, pursued the

retreating Americans, into the Jerseys, through Elizabethtown, Neward and

Brunswick. In the latter town he was ordered to halt, where he remained

for eight days, when General Howe, with the army, moved forward, and

reached Princeton in the afternoon of November 17th.

The army now went into winter

quarters. The Royal Highlanders were stationed at Brunswick, and Fraser’s

Highlanders quartered at Amboy. Afterwards the Royal Highlanders were

ordered to the advanced posts, being the only British regiment in the

front, and forming the line of defence at Mt. Holly. After the disaster to

the Hessians at Trenton, the Royal Highlanders were ordered to fall back

on the light infantry at Princeton.

Lord Cornwallis, who was in New York

at the time of the defeat of the Hessians, returned to the army and moved

forward with a force consisting of the grenadiers, two brigades of the

line, and the two Highland regiments. After much skirmishing in advance he

found Washington posted on some high ground beyond Trenton. Lord

Cornwallis declaring "the fox cannot escape me," planned to assault

Washington on the following morning, but while he slept the American

commander, marched to his rear and fell upon that part of the army left at

Princeton. Owing to the suddenness of Washington’s attacks upon Trenton

and Princeton and the vigilance he manifested the British outposts were

withdrawn and concentrated at Brunswick where lord Cornwallis established

his headquarters.

The Royar Highlanders, on January 6,

1777 were sent to the village of Pisquatua on the line of communication

between New York and Brunswick by Amboy. This was a post of great

importance, for it kept open the route by which provisions were sent for

the forces at Brunswick. The duty was severe and the winter rigorous. As

the homes could not accommodate half the men, officers and soldiers sought

shelter in barns and sheds, always sleeping in their body—clothes, for the

Americans gave them but little quietude. The Americans, however, did not

make any regular attack on the post till May 10th, when, at four in the

morning, the divisions of Generals Maxwell and Stephens, attempted to

surprise the Highlanders. Advancing with great caution they were not

preceived until they rushed upon the pickets. Although the Highlanders

were surprised, they held their position until the reserve pickets came to

their assistance, when they retired disputing every foot, to afford the

regiment time to form, and come to their relief. Then the Americans were

driven back with precipitation, leaving upwards of two hundred men, in

killed and wounded, The Highlanders, pursuing with eagerness, were

recalled with great difficulty. On this occasion the Royal Highlanders had

three sergeants and nine privates killed: and Captain Duncan Macpherson,

Lieutenant William Stewart, three sergeants, and thirty-five privates

wounded.

"On this occasion, Sergeant

Macgregor, whose company was immediately in the rear of the picquet,

rushed forward to their support, with a few men who happened to have their

arms in their hands, when the enemy commenced the attack. Being severely

wounded, he was left insensible on the ground. When the picquet was

overpowered, and the few survivors forced to retire, Macgregor, who had

that day put on a new jacket with silver lace, having besides, large

silver buckles in his shoes, and a watch, attracted the notice of an

American soldier, who deemed him a good prize. The retreat of his friends

not allowing him time to strip the sergeant on the spot, he thought the

shortest way was to take him on his back to a more convenient distance. By

this time Macgregor began to recover; and, perceiving whither the man was

carrying him, drew his dirk, and, grasping him by the throat, swore that

he would run him through the breast, if he did not turn back and carry him

to the camp. The American, finding this argument irresistible, complied

with the request, and, meeting Lord Cornwallis (who had come up to the

support of the regiment when he heard the firing) and Colonel Stirling,

was thanked for his care of the sergeant; but he honestly told him, that

he only conveyed him thither to save his own life. Lord Cornwallis gave

him liberty to go whithersoever he chose."

Summer being well advanced, Sir

William Howe made preparations for taking the field. The Royal

Highlanders, along with the 13th, 17th, and 44th regiments were put under

the command of General Charles Gray. Failing to draw Washington from his

secure position at Middlebrook, General Howe resolved to change the seat

of war, and accordingly embarked thirty-six battalions of British and

Hessians, and sailed for the Chesapeake. Before the embarkation, the Royal

Highlanders received one hundred and seventy recruits from Scotland, who,

as they were all of the best description, more than supplied the loss that

had been sustained.

After a tedious voyage the army, on

August 24th, landed at Elk Ferry. It did not begin the march until

September 3rd, for Philadelphia. In the meantime Washington marched across

the country and took up a position at Red Clay Creek, but having his

headquarters at Wilmington. His effective force was about eleven thousand

men while that of General Howe was eighteen thousand strong.

The two armies met on September

11th, and fought the battle of Brandywine. During the battle, lord

Cornwallis, with four battalions of British grenadiers and light infantry,

the Hessian grenadiers, a party of the 71st Highlanders, and the third and

fourth brigades, made a circuit of some miles, crossed Jefferis’ Ford

without opposition, and turned short down the river to attack the American

right. Washington, being apprised of this movement, detached General

Sullivan, with all the force he could spare, to thwart the design. General

Sullivan, having advantageously posted his men, lord Cornwallis was

obliged to consume some time in forming a line of battle. An action then

took place, when the Americans were driven through the woods towards the

main army. Meanwhile General Knyphausen, with his division, made

demonstrations for crossing at Chad’s Ford, and as soon as he knew from

the firing of cannon that lord Cornwallis had succeeded, he crossed the

river and carried the works of the Amercans. The approach of night ended

the conflict. The Amercans rendezvoused at Chester, and the next day

retreated towards Philadelphia, and encamped near Germantown.

The British had fifty officers

killed and wounded and four hundred and thirty-eight rank and file. The

battalion companies of the 42nd being in the reserve, sustained no loss,

as they were not brought into action; but of the light company, which

formed part of the light brigade, six privates were killed, and one

sergeant and fifteen privates wounded.

On the night of September 20th,

General Gray was detached with the 2nd light infantry and the 42nd and

44th regiments to cut off and destroy the corps of General Wayne. They

marched with great secrecy and came upon the camp at midnight, when all

were asleep save the pickets and guards, who were overpowered without

causing an alarm. The troops then rushed forward, bayoneted three hundred

and took one hundred Americans prisoners. The British loss was three

killed and several wounded.

On the 26th the British army took

peaceable possession of Philadelphia. In the battle of Germantown, fought

on the morning of October 4, 1777, the Highlanders did not participate.

The next enterprise in which the

42nd was engaged was under General Gray, who embarked with that regiment,

the grenadiers and the light infantry brigade, for the purpose of

destroying a number of privateers, with their prizes at New Plymouth. On

September 5, 1778, the troops landed on the banks of the Acushnet river,

and having destroyed seventy vessels, with all the cargoes, stores,

wharfs, and buildings, along the whole extent of the river, the whole were

re-embarked the following day and returned to New York.

The British army during the

Revolutionary struggle took the winter season for a period of rest,

although engaging more or less in marauding expeditions. On February 25,

1779, Colonel Stirling, with a detachment consisting of the light infantry

of the Guards and the 42nd, was ordered to attack a post at Elizabethtown,

in New Jersey, which was taken without opposition.

In April following the

Highland regiment was employed on an expedition to the Chesapeake, to

destroy the stores and merchandise at Portsmouth, in Virginia. They were

again employed with the Guards and a corps of Hessians in another

expedition under General Mathews, which sailed on the 30th, under the

convoy of Sir George Collier, in the Reasonable, and several ships of war,

and reached their destination on May 10th, when the troops landed on the

glebe on the western bank of Elizabeth. After fulfilling the object of the

expedition they returned to New York in good time for the opening of the

campaign, which commenced by the capture, on the part of the British, of

Verplanks and Stony Point. A garrison of six hundred men, among whom were

two companies of Fraser’s Highlanders, took possession of Stony Point.

Washington planned its capture which was executed by General Wayne. Soon

after General Wayne moved against Verplanks, which held out till the

approach of the light infantry and the 42nd, then withdrew his forces and

evacuated Stony Point. Shortly after, Colonel Stirling was appointed

aide-de-camp to the king, when the command of the 42nd devolved on Major

Charles Graham, to whom was entrusted the command of the posts of Stony

Point and Verplanks, together with his own regiment, and a detachment of

Fraser’s Highlanders, under Major Ferguson. This duty was the more

important, as the Americans surrounded the posts in great numbers, and

desertion had become so frequent among a corps of provincials, sent as a

reinforcement, that they could not be trusted on any military duty,

particularly on those duties which were most harassing. In the month of

October these posts were withdrawn and the regiment sent to Greenwich,

near New York.

The winter of 1779 was the

coldest that had been known for forty years; and the troops, although in

quarters, suffered more from that circumstance than in the preceding

winter when in huts. But the Highianders met with a misfortune that

greatly grieved them, and which tended to deteriorate, for several years,

the heretofore irreproachable character of the Royal Highland Regiment. In

the autumn of this year a draft of one hundred and fifty men, recruits

raised principally from the refuse of the streets of London and Dublin,

was embarked for the regiment by orders from the inspector-general at

Chatham. These men were of the most depraved character, and of such

dissolute habits, that one-half of them were unfit for service; fifteen

died in the passage, and seventy-five were sent to the hospital from the

transport as soon as they disembarked. The infusion of such immoral

ingredients must necessarily have a deleterious effect. General Stirling

made a strong remonstrance to the commander-in-chief, in consequence of

which these men were removed to the 26th regiment, in exchange for the

same number of Scotchmen. The introduction of these men into the regiment

dissolved the charm which, for nearly forty years, had preserved the

Highlanders from contamination. During that long period there were but few

courts-martial, and, for many years, no instance of corporal punishment

occurred.

With the intention of

pushing the war with vigor, the new commander-in-chief. Sir Henry Clinton,

who had succeeded Sir William Howe, in May, 1778, resolved to attack

Charleston, the capital of South Carolina. Having left General Knyphausen

in command at New York, General Clinton with his army set sail December

26, 1779. Such was the severity of the weather, however, that, although

the voyage might have been accomplished in ten days, it was February 11,

1780, before the troops disembarked on John’s Island, thirty miles from

Charleston. So great were the impediments to be overcome, and so cautious

was the advance of the general, that it was March 29th before they crossed

the Ashley river. The following day they encamped opposite the American

lines. Ground was broken in front of Charleston on April 1st. General

Lincoln, who commanded the American forces, had strengthened the place in

all its defences, both by land and water, in such a manner as to threaten

a siege that would be both tedious and difficult. When General Clinton,

anticipating the nature of the works he desired to capture, sent for the

Royal Highlanders and Queen’s Rangers to join him, which they did on April

18th, having sailed from New York on March 31st. The siege proceeded in

the usual way until May 12th, when the garrison surrendered prisoners of

war. The loss of the British forces on this occasion consisted of

seventy-six killed and one hundred

and eighty—nine wounded; and that of the 42nd,

Lieutenant Macleod and nine privates killed, and Lieutenant Alexander

Grant and fourteen privates wounded.

After Sir

Henry Clinton had taken possession of

Charleston, the 42nd and light infantry were ordered to Monck’s Corner as

a foraging party, and, returning on the 2nd, they embarked June 4th for

New York, along with the Grenadiers and Elessians. After being stationed

for a time on Staten Island, Valentine’s Hill, and other stations in New

York, went into winter quarters in the city. About this time one hundred

recruits were received from Scotland, all young men, in

the full vigor of health, and ready for

immediate service. From this period, as the regiment was not engaged in

any active service during the war, the changes in encampments are too

trifling to require notice.

On April 28, 1782, Major Graham

succeeded to the

lieutenant-colonelcy of the Royal

Highland Regiment, and Captain Walter Home of the fusileers became major.

While the regiment was stationed at

Paulus Hook several of the men deserted to the Americans. This

unprecedented and unlooked for

event occasioned much surprise and various causes were ascribed for it but

the prevalent opinion was that the men had received from the 26th

regiment, and who had been made prisoners at Saratoga, had been promised

lands and other indulgences while prisoners to the Americans. One of these

deserters, a man named Anderson, was soon afterwards taken, tried by

court—martial, and shot. This was the first instance of an execution in

the regiment since the mutiny of 1743. The regiment remained at Paulus

Hook till the conclusion of the war, when the establishment was reduced to

eight companies of fifty men each. The officers of the ninth and tenth

companies were not put on half-pay, but kept as supernumeraries to fill up

vacancies as they occurred in the regiment. A number of the men were

discharged at their own request, and their places supplied by those who

wished to remain in the country, instead of going home with their

regiments. These were taken from Fraser’s and Macdonald

Highlanders, and from the Edinburgh and

duke of Hamilton’s regiments.

The

42nd left New York for Halifax, Nova Scotia,

on October 22, 1783, where they remained till the year 1786, when

the battalion embarked and sailed for Cape Breton, two companies being

detached to tile island of St. John. In the month of August, 1789. the

regiment embarked for England, and landed in Portsmouth in October. In

May, 1790, they arrived in

Glasgow.

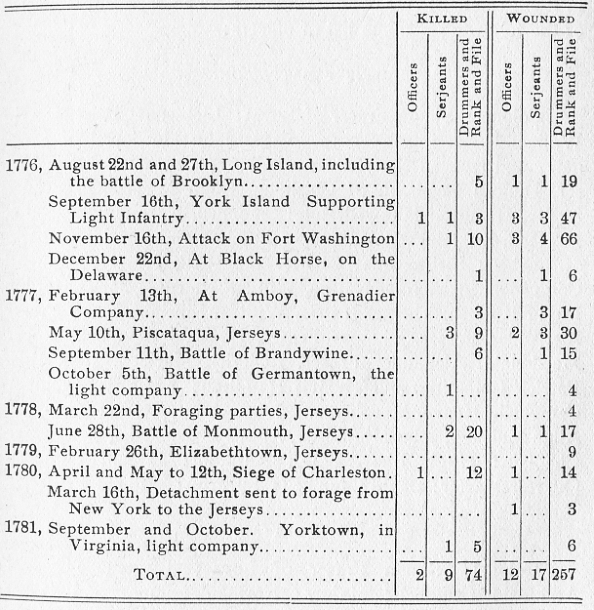

During

the American Revolutionary War the loss

of the Royal Highlanders was as follows:

FRASER’S HIGHLANDERS.

The breaking

out of hostilities in America in 1775

determined the English government to revive Fraser’s Highlanders.

Although disinherited of his estates

Colonel Fraser, through the influence of clan feeling, was enabled to

raise twelve hundred and fifty men

in 1757, it was believed, since his estates

had been restored in 1772, he could readily raise a strong

regiment. So, in 1775, Colonel Fraser received letters for raising a

Highland regiment of two battalions. With ease he raised two thousand

three hundred and forty Highlanders, who were marched up to Stirling, and

thence to Glasgow in April, 1776.

This corps had in it six chiefs of clans besides himself. The regiment

consisted of the following nominal list of officers:

FIRST BATTALION.

Colonel: Simon Fraser of Lovat;

Lieutenant-Colonel: Sir William Erskine of Torry; Majors: John Macdonell

of Lochgarry and Duncan Macpherson of Cluny; Captains: Simon Fraser,

Duncan Chisholm of Chisholm, Colin Mackenzie, Francis Skelly, Hamilton

Maxwell, John Campbell, Norman Macleod of Macleod, Sir James Baird of