|

A range of mountains forming a lofty

and somewhat shattered rampart, commencing in the county of Aberdeen,

north of the river Don, and extending in a south-west course across the

country, till it terminates beyond Ardmore, in the county of Dumbarton,

divides Scotland into two distinct parts. The southern face of these

mountains is bold, rocky, dark and precipitous. The land south of this

line is called the Lowlands, and that to the north, including the range,

the Highlands. The maritime outline of the Highlands is also bold and

rocky, and in many places deeply indented by arms of the sea. The northern

and western coasts are fringed with groups of islands. The general surface

of the country is mountainous, yet capable of supporting innumerable

cattle, sheep and deer. The scenery is nowhere excelled for various forms

of beauty and sublimity. The lochs and bens have wrought upon the

imaginations of historians, poets and novel ists.

The inhabitants living within these

boundaries were as unique as their bens and glens. From the middle of the

thirteenth century they have been distinctly marked from those inhabiting

the low countries, in consequence of which they exhibit a civilization

peculiarly their own. By their Lowland neighbors they were imperfectly

known, being generally regarded as a horde of savage thieves, and their

country as an impenetrable wilderness. From this judgment they made no

effort to free themselves, but rather inclined to confirm it. The language

spoken by the two races greatly varied which had a tendency to establish a

marked characteristic difference between them. For a period of seven

centuries the entrances or passes into the Grampians constituted a

boundary between both the people

and

their language. At the south the Saxon language was universally spoken,

while beyond the range the Gaelic formed the mother tongue, accompanied by

the plaid, the claymore and other specialties which accompanied Highland

characteristics. Their language was one of the oldest and least mongrel

types of the great Aryan family of speech.

The country in which the Gaelic was

in common use among all classes of people may be defined by a line drawn

from the western opening of the Pentland Frith, sweeping around St. Kilda,

from thence embracing the entire cluster of islands to the east and south,

as far as Arran; thence to the Mull of Kintyre, re-entering the mainland

at Ardmore, in Dumbartonshire, following the southern face of the

Grampians to Aberdeenshire, and ending on the north-east point of

Caithness.

For a period of nearly two hundred

years the Highlander has been an object of study by strangers. Travellers

have written concerning them, but dwelt upon such points as struck their

fancy. A people cannot be judged by the jottings of those who have not

studied the question with candor and sufficient information. Fortunately

the Highlands, during the present century, have produced men who have

carefuly set forth their history, manners and customs. These men have

fully weighed the questions of isolation, mode of life, habits of thought,

and wild surroundings, which developed in the Highlander firmness of

decision, fertility in resource, ardor in friendship, love of country, and

a generous enthusiasum, as well as a system of government.

The Highlanders were tall, robust,

well formed and hardy. Early marriages were unknown among them, and it was

rare for a female of puny stature and delicate constitution to be honored

with a husband. They were not obliged by art in forming their bodies, for

Nature acted her part bountifully to them, and among them there are but

few bodily imperfections.

The division of the people into

clans, tribes or families, under separate chiefs, constituted the most

remarkable circumstance in their political condition, which ultimately

resulted in many of their peculiar sentiments, customs and institutions.

For the most part the monarchs of Scotland had left the people alone, and,

therefore, had but little to do in the working out of their destiny. Under

little or no restraint from the State, the patriarchal form of government

became universal.

It is a singular fact that although

English ships had navigated the known seas and transplanted colonies, yet

the Highlanders were but little known in London, even as late as the

beginning of the eighteenth century. To the people of England it would

have been a matter of surprise to learn that in the north of Great

Britain, and at a distance of less than five hundred miles from their

metropolis, there were many miniature courts, in each of which there was a

hereditary ruler, attended by guards, armor-bearers, musicians, an orator,

a poet, and who kept a rude state, dispensed justice, exacted tribute,

waged war, and contracted treaties.

The ruler of each clan was called a

chief, who was really the chief man of his family. Each clan was divided

into branches who had chieftains over them. The members of the clan

claimed consanguinity to the chief. The idea never entered into the mind

of a Highlander that the chief was anything more than the head of the

clan. The relation he sustained was subordinate to the will of the people.

Sometimes his sway was unlimited, but necessarily paternal. The tribesmen

were strongly attached to the person of their chief. He stood in the light

of a protector, who must defend them and right their wrongs. They rallied

to his support, and in defense they had a contempt for danger. The sway of

the chief was of such a nature as to cultivate an imperishable love of

independence, which was probably strengthened by an exceptional hardiness

of character.

The chief generally resided among

his clansmen, and his castle was the court where rewards were distributed

and distinctions conferred. All disputes were settled by his decision.

They followed his standard in war, attended him in the chase, supplied his

table and harvested the products of his fields. His nearest kinsmen became

sub-chiefs, or chieftains, held their lands and properties from him, over

which they exercised a subordinate jurisdiction. These became counsellors

and assistants in all emergencies. One chief was distinguished from

another by having a greater number of attendants, and by the exercise of

general hospitality, kindness and condescension. At the castle everyone

was made welcome, and treated according to his station, with a degree of

courtesy and regard for his feelings. This courtesy not only raised the

clansman in his own estimation, but drew the ties closer that bound him to

his chief.

While the position of chief was

hereditary, yet the heir was obliged in honor to give a specimen of his

valor, before he was assumed or declared leader of his people. Usually he

made an incursion upon some chief with whom his clan had a feud. He

gathered around him a retinue of young men who were ambitious to signalize

themselves. They were obliged to bring, by open force, the cattle they

found in the land they attacked, or else die in the attempt. If successful

the youthful chief was ever after reputed valiant and worthy of the

government. This custom being reciprocally used among them, was not

reputed robbery; for the damage which one tribe sustained would receive

compensation at the inauguration of its chief.

Living in a climate, severe in

winter, the people inured themselves to the frosts and snows, and cared

not for the exposure to the severest storms or fiercest blasts. They were

content to lie down, for a night’s rest, among the heather on the

hillside, in snow or rain, covered only by their plaid. It is related that

the laird of Keppoch, chieftain of a branch of the MacDonalds, in a winter

campaign against a neighboring clan, with whom he was at war, gave orders

for a snow-ball to lay under his head in the night; whereupon, his

followers objected, saying, "Now we despair of victory, since our leader

has become so effeminate he can’t sleep without a pillow."

The high sense of honor cultivated

by the relationship sustained to the chief was reflected by the most

obscure inhabitant. Instances of theft from the dwelling houses seldom

ever occurred, and highway robbery was never known. In the interior all

property was safe without the security of locks, bolts and bars. In summer

time the common receptacle for clothes, cheese, and everything that

required air, was an open barn or shed. On account of wars, and raids from

the neighboring clans, it was found necessary to protect the gates of

castles.

The Highlanders were a brave and

high-spirited people, and living under a turbulent monarchy, and having

neighbors, not the most peaceable, a warlike character was either

developed or else sustained. Inured to poverty they acquired a hardihood

which enabled them to sustain severe privations. In their school of life

it was taught to consider courage an honorable virtue and cowardice the

most disgraceful failing. Loving their native glen, they were ever ready

to defend it to the last extremity. Their own good name and devotion to

the clan emulated and held them to deeds of daring.

it was hazardous for a chief to

engage in war without the consent of his people; nor could deception be

practiced successfully. Lord Murray raised a thousand men on his father’s

and lord Lovat’s estates, under the assurance that they were to serve king

James, but in reality for the service of king William. This was discovered

while Murray was in the act of reviewing them; immediately they broke

ranks, ran to an adjoining brook, and, filling their bonnets with water,

drank to king James’ health, and then marched off with pipes playing to

join Dundee.

The clan was raised within an

incredibly short time. When a sudden or important emergency demanded the

clansmen the chief slew a goat, and making a cross of light wood, seared

its extremities with fire, and extinguished them in the blood of the

animal. This was called the Fiery

Cross, or Cross

of Shame, because disobedience to what the symbol implied inferred infamy.

It was delivered to a swift trusty runner, who with the utmost speed

carried it to the first hamlet and delivered it to the principal person

with the word of rendezvous. The one receiving it sent it with the utmost

despatch to the next village; and thus with the utmost celerity it passed

through all the district which owed allegiance to the chief, and if the

danger was common, also among his neighbors and allies. Every man between

the ages of sixteen and sixty, capable of bearing arms, must immediately

repair to the place of rendezvous, in his best arms and accountrements. In

extreme cases childhood and old age obeyed it. He who failed to appear

suffered the penalties of fire and sword, which were emblematically

denounced to the disobedient by the bloody and burnt marks upon this

warlike signal.

In the camp, on the march, or in

battle, the clan was commanded by the chief. If the chief was absent, then

some responsible chieftain of the clan took the lead. In both their slogan

guided them, for every clan had its own war-cry. Before commencing an

attack the warriors generally took off their jackets and shoes. It was

long remembered in Lochabar, that at the battle of Killiecrankie, Sir Ewen

Cameron, at the head of his clan, just before engaging in the conflict,

took from his feet, what was probably the only pair of shoes, among his

tribesmen. Thus freed from everything that might impede their movements,

they advanced to the assault, on a double-quick, and when within a few

yards of the enemy, would pour in a volley of musketry and then rush

forward with claymore in hand, reserving the pistol and dirk for close

action. When in close quarters the bayonets of the enemy were received on

their targets; thrusting them aside, they resorted to the pistol and dirk

to complete the confusion made by the musket and claymore. In a close

engagement they could not be withstood by regular troops.

Another kind of warfare to which the

Highlander was prone, is called Creach, or foray, but really the

lifting of cattle. The Creach received the approbation of the clan,

and was planned by some responsible individual. Their predatory raids were

not made for the mere pleasure of plundering their neighbors. To them it

was legitimate warfare, and generally in retaliation for recent injuries,

or in revenge of former wrongs. They were strict in not offending those

with whom they were in amity. They had high notions of the duty of

observing faith to allies and hospitality to guests. They were warriors

receiving the lawful prize of war, and when driving the herds of the

Lowland farmers up the pass which led to their native glen considered it

just as legitimate as did the Raleighs and Drakes when they divided the

spoils of Spanish galleons. They were not always the aggressors. Every

evidence proves that they submitted to grievances before resorting to

arms. When retaliating it was with the knowledge that their own lands

would be exposed to rapine. As an illustration of the view in which the

Creach was held, the case of Donald Cameron may be taken, who was

tried in 1752, for cattle stealing, and executed at Kinloch Rannoch. At

his execution he dwelt with surprise and indignation on his fate. He had

never committed murder, nor robbed man or house, nor taken anything but

cattle, and only then when on the grass, from one with whom he was at

feud; why then should he be punished for doing that which was a common

prey to all?

After a successful expedition the

chief gave a great entertainment, to which all the country around was

invited. On such an occasion whole deer and beeves were roasted and laid

on boards or hurdles of rods placed on the rough trunks of trees, so

arranged as to form an extended table. During the feast spirituous liquors

went round in plenteous libations. Meanwhile the pipers played, after

which the women danced, and, when they retired, the harpers were

introduced.

Great feasting accompanied a

wedding, and also the burial of a great personage. At the burial of one of

the Lords of the Isles, in Iona, nine hundred cows were consumed.

The true condition of a people may

be known by the regard held for woman. The beauty of their women was

extolled in song. Small eye-brows was considered as a mark of beauty, and

names were bestowed upon the owners from this feature. No country in

Europe held woman in so great esteem as in the Highlands of Scotland. An

unfaithful, unkind, or even careless husband was looked upon as a monster.

The parents gave dowers according to their means, consisting of cattle,

provisions, farm stocking, etc. Where the parents were unable to provide

sufficiently, then it was customary for a newly-married couple to collect

from their neighbors enough to serve the first year.

The marriage vow was sacredly kept.

Whoever violated it, whether male or female, which seldom ever occurred,

was made to stand in a barrel of cold water at the church door, after

which the delinquent, clad in a wet canvas shirt, was made to stand before

the congregation, and at the close of service, the minister explained the

nature of the offense. A separation of a married couple among the common

people was almost unknown. However disagreeable the wife might be, the

husband rarely contemplated putting her away. Being his wife, he bore with

her failings; as the mother of his children he continued to support her; a

separation would have entailed reproach upon his posterity.

Young married women never wore any

close head-dress. The hair, with a slight ornament was tied with ribbons;

but if she lost her virtue then she was obliged to wear a cap, and never

appear again with her head uncovered.

Honesty and fidelity were sacredly

inculcated, and held to be virtues which all should be careful to

practice. Honesty and fair dealing were enforced by custom, which had a

more powerful influence, in their mutual transactions, than the legal

enactments of later periods. Insolvency was considered disgraceful, and

prima facie a crime. Bankrupts surrendered their all, and then clad in

a party colored clouted garment, with hose of different sets, had their

hips dashed against a stone in presence of the people, by four men, each

seizing an arm or a leg. Instances of faithfulness and attachment are

innumerable. The one most frequently referred to occurred during the

battle of Inverkeithing, between the Royalists and the troops of Cromwell,

during which seven hundred and fifty of the Mac Leans, led by their chief,

Sir Hector, fell upon the field. In the heat of the conflict, eight

brothers of the clan sacrificed their lives in defense of their chief.

Being hard pressed by the enemy, and stoutly refusing to change his

position, he was supported and covered by these intrepid brothers. As each

brother fell another rushed forward, covering his chief with his body,

crying Fear eil airson Eachainn (Another for Hector). This phrase

has continued ever since as a proverb or watch-word when a man encounters

any sudden danger that requires instant succor.

The Highlands of Scotland is the

only country of Europe that has never been distracted by religious

controversy, or suffered from religious persecution. This possibly may

have been due to their patriarchal form of government. The principles of

the Christian religion were warmly accepted by the people, and cherished

with a strong feeling. In their religious convictions they were peaceable

and unobtrusive, never arming themselves with Scriptural texts in order to

carry on offensive operations. Never being perplexed by doubt, they

desired no one to corroborate their faith, and no inducement could

persuade them to strut about in the garb of piety in order to attract

respect. The reverence for the Creator was in the heart, rather than upon

the lips. In that land papists and protestants lived together in charity

and brotherhood, earnest and devoted in their churches, and in contact

with the world, humane and charitable. The pulpit administrations were

clear and simple, and blended with an impressive and captivating spirit.

All ranks were influenced by the belief that cruelty, oppression, or other

misconduct, descended to the children, even to the third and fourth

generations.

To a certain extent the religion of

the Highlander was blended with a belief in ghosts, dreams and visions.

The superstitions of the Gael were distinctly marked, and entirely too

important to be overlooked. These beliefs may have been largely due to an

uncultivated imagination and the narrow sphere in which he moved. His

tales were adorned with the miraculous and his poetry contained as many

shadowy as substantial personages. In numerable were the stories of

fairies, kelpies, urisks, witches and prophets or seers. Over him watched

the Daoine Shi’, or men of peace. In the glens and corries were heard the

eerie sounds during the watches of the night. Strange emotions were

aroused in the hearts of those who heard the raging of the tempest, the

roaring of the swollen rivers and dashing of the water-fall, the thunder

peals echoing from crag to crag, and the lightning rending rocks and

shivering to pieces the trees. When a reasonable cause could not be

assigned for a calamity it was ascribed to the operations of evil spirits.

The evil one had power to make compacts, but against these was the virtue

of the charmed circle. One of the most dangerous and malignant of beings

was the Water-kelpie, which allured women and children into its element,

where they were drowned, and then became its prey. It could skim along the

surface of the water, and browse by its side, or even suddenly swell a

river or loch, which it inhabited, until an unwary traveller might be

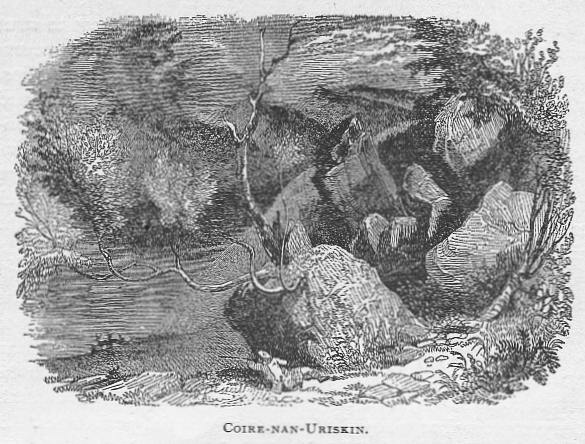

engulfed. The Urisks were half-men, half-spirits, who, by kind treatment,

could be induced to do a good turn, even to the drudgeries of a farm.

Although scattered over the whole Highlands, they assembled in the

celebrated cave— Coire- nanUriskin -

situated near the base of Ben Venue, in Aberfoyle.

"By many a bard, in Celtic tongue,

Has Coir-nan-Uriskin been sung:

A softer name the Saxons gave,

And call’d the grot the Goblin-cave,

* * * * *

Gray Superstition’s whisper dread

Debarr’d the spot to vulgar tread;

For there, she said, did fays resort,

And satyrs hold their sylvan court."

— Lady of the Lake.

The Daoine Shi’ were believed to be

a peevish, repining race of beings, who, possessing but a scant portion of

happiness, envied mankind their more complete and substantial enjoyments.

They had a sort of a shadowy happiness, a tinsel grandeur, in their

subterranean abodes. Many persons had been entertained in their secret

retreats, where they were received into the most splendid apartments, and

regaled with sumptuous banquets and delicious wines. Should a mortal,

however, partake of their dainties, then he was forever doomed to the

condition of shi’ick, or Man of

Peace. These banquets and all the

paraphernalia of their homes were but deceptions. They dressed in green,

and took offense at any mortal who ventured to assume their favorite

color. Hence, in some parts of Scotland, green was held to be unlucky to

certain tribes and counties. The men of Caithness alleged that their bands

that wore this color were cut off at the battle of Flodden; and for this

reason they avoided the crossing of the Ord on a Monday, that being the

day of the week on which the ill-omened array set forth. This color was

disliked by both those of the name of Ogilvy and Graham. The greatest

precautions had to be taken against the Daoine Shi’ in order to prevent

them from spiriting away mothers and their newly-born children. Witches

and prophets or seers, were frequently consulted, especially before going

into battle. The warnings were not always received with attention. Indeed,

as a rule, the chiefs were seldom deterred from their purpose by the

warnings of the oracles they consulted.

It has been advocated that the

superstitions of the Highlanders, on the whole, were elevating and

ennobling, which plea cannot well be sustained. It is admitted that in

some of these superstitions there were lessons taught which warned against

dishonorable acts, and impressed what to them were attached disgrace both

to themselves and also to their kindred; and that oppression, treachery,

or any other wickedness would be punished alike in their own persons and

in those of their descendants. Still, on the other hand, it must not be

forgotten that the doctrines of rewards and punishments had for

generations been taught them from the pulpit. How far these teachings had

been interwoven with their superstitions would be an impossible problem to

solve.

The Highlanders were poetical. Their

poets, or bards, were legion, and possessed a marked influence over the

imaginations of the people. They excited the Gael to deeds of valor. Their

compositions were all set to music,—many of them composing the airs to

which their verses were adapted. Every chief had his bard. The aged

minstrel was in attendance on all important occasions: at birth, marriage

and death; at succession, victory, and defeat. He stimulated the warriors

in battle by chanting the glorious deeds of their ancestors; exhorted them

to emulate those distinguished

examples, and, if possible, shed a still greater lustre on the warlike

reputation of the clan. These addresses were delivered with great

vehemence of manner, and never failed to raise the feelings of the

listeners to the highest pitch of enthusiasm. When the voice of the bard

was lost in the din of battle then the piper raised the inspiring sound of

the pibroch. When the conflict was over the bard and the piper were again

called into service—the former to honor the memory of those who had

fallen, to celebrate the actions of the survivors, and excite them to

further deeds of valor. The piper played the mournful Coronach for the

slain, and by his notes reminded the survivors how honorable was the

conduct of the dead.

The bards were the

senachies or historians of the clans, and were recognized as a very

important factor in society. They represented the literature of their

times. In the absence of books they constituted the library and learning

of the tribe. They were the living chronicles of past events, and the

depositories of popular poetry. Tales and old poems were known to special

reciters. When collected around their evening fires, a favorite pastime

was a recital of traditional tales and poetry. The most acceptable guest

was the one who could rehearse the longest poem or most interesting tale.

Living in the land of Ossian, it was natural to ask a stranger, "Can you

speak of the days of Fingal ?" If the answer was in the affirmative, then

the neighbors were summoned, and poems and old tales would be the order

until the hour of midnight. The reciter threw into the recitation all the

powers of his soul and gave vent to the sentiment. Both sexes always

participated in these meetings.

The poetry was not always

of the same cast. It varied as greatly as were the moods of the composer.

The sublimity of Ossian had its opposite in the biting sarcasm and

trenchant ridicule of some of the minor poets.

Martin, who travelled in

the Western Isles, about 1695, remarks: "They are a very sagacious people,

quick of apprehension, and even the vulgar exceed all those of their rank

and education I ever yet saw in any other country. They have a great

genius for music and mechanics. I have observed several of their children

that before they could speak were capable to distinguish and make choice

of one tune before another upon a violin; for they appeared always uneasy

until the tune which they fancied best was played, and then they expressed

their satisfaction by the motions of their head and hands. There are

several of them who invent tunes already taking in the South of Scotland

and elsewhere. Some musicians have endeavored to pass for first inventors

of them by changing their name, but this has been impracticable; for

whatever language gives the modern name, the tune still continues to speak

its true original. * * * Some of both sexes have a quick vein of poetry,

and in their language— which is very emphatic—they compose rhyme and

verse, both which powerfully affect the fancy. And in my judgment (which

is not singular in this matter) with as great force as that of any ancient

or modern poet I ever read. They have generally very retentive memories;

they see things at a great distance. The unhappiness of their education,

and their want of converse with foreign nations, deprives them of the

opportunity to cultivate and beautify their genius, which seems to have

been formed by nature for great attainments." ["Description of the Western

Islands," pp. 199, 200.]

The piper was an important

factor in Highland society. From the earliest period the Highlanders were

fond of music and dancing, and the notes of the bagpipe moved them as no

other instrument could. The piper performed his duty in peace as well, as

in war. At harvest homes, Hallowe’en christenings, weddings, and evenings

spent in dancing, he was the hero for the occasion. The people took

delight in the high-toned warlike notes to which they danced, and were

charmed with the solemn and melancholy airs which filled up the pauses.

Withal the piper was a humorous fellow and was full of stories.

The harp was a very ancient

musical instrument, and was called clarsach. It had thirty strings, with

the peculiarity that the front arm was not perpendicular to the sounding

board, but turned considerably towards the left, to afford a greater

opening for the voice of the performer, and this construction showed that

the accompaniment of the voice was a chief province of the harper. Some

harps had but four strings. Great pains were taken to decorate the

instrument. One of the last harpers was Roderick Morrison, usually called

Rory Dali. He served the chief of Mac Leod. He flourished about 1650.

Referring again to Gaelic

music it may be stated that its air

can easily be detected. It is quaint and pathetic,

moving one with intervals singular in their irregularity. When compared

with the common airs among the English, the two are found to be quite

distinct. The airs to which "Scots wha hae," "Auld Langsyne," "Roy’s

Wife," "O a’ the Airts," and "Ye Banks and Braes" are written, are such

that nothing similar can be found in England. They are Scottish. Airs of

precisely the same character are, however, found among all Keltic races.

No portraiture of a Highlander would

be complete without a description of his garb. His costume was as

picturesque as his native hills. It was well adapted to his mode of life.

By its lightness and freedom he

was enabled to use his limbs and handle

his arms with ease and dexterity. He moved with great swiftness. Every

clan had a plaid of its own, differing in the combination of its colors

from all others. Thus a Cameron, a Mac Donald, a Mac Kenzie, etc., was

known by his plaid; and in like manner the Athole, Glenorchy, and other

colors of different districts were easily discernible.. Besides those of

tribal designations, industrious housewives had patterns, distinguished by

the set, superior quality, and fineness of the cloth, or brightness and

variety of the colors. The removal of tenants rarely occurred, and

consequently, it was easy to preserve and perpetuate any particular set,

or pattern, even among the lower orders. The plaid was made of fine wool,

with much ingenuity in sorting the colors. In order to give exact patterns

the women had before them a piece of wood with every thread of the stripe

upon it. Until quite recently it was believed that the plaid, philibeg and

bonnet formed the ancient garb. The philibeg or kilt, as distinct from the

plaid, in all probability, is comparatively modern. The truis, consisting

of breeches and stockings, is one piece and made to fit closely to the

limbs, was an old costume. The belted plaid was a piece of tartan two

yards in breadth, and four in length. It surrounded the waist in great

folds, being firmly bound round the loins with a leathern belt, and in

such manner that the lower side fell down to the middle of the knee joint.

The upper part was fastened to the left shoulder with a large brooch or

pin, leaving the right arm uncovered and at full liberty. In wet weather

the plaid was thrown loose, covering both shoulders and body. When the use

of both arms was required, it was fastened across the breast by a large

bodkin or circular brooch. The sporan, a large purse of goat or badger’s

skin, usually ornamented, was hung before. The bonnet completed the garb.

The garters were broad and of rich colors, forming a close texture which

was not liable to wrinkle. The kilted-plaid was generally double, and when

let down enveloped the whole person, thus forming a shelter from the

storm. Shoes and stockings are of comparatively recent times. In lieu of

the shoe untanned leather was tied with thongs around the feet. Burt,

writing about the year 1727, when some

innovations had been made, says: "The Highland dress consists of a bonnet

made of thrum without a brim, a short coat, a waistcoat longer by five or

six inches, short stockings, and brogues or pumps without heels * * *

Few besides gentlemen wear the

truis, that is, the breeches and stockings all of one piece and drawn on

together; over this habit they wear a plaid, which is usually three yards

long and two breadths wide, and the whole garb is made of checkered tartan

or plaiding; this with the sword and pistol, is called a full dress,

and to a well proportioned man with any tolerable air, it makes an

agreeable figure." ["Letters

from the North," Vol. II., p. 167.]

The plaid was the undress of the ladies, and to a woman who adjusted it

with an important air, it proved to be a becoming veil. It was made of

silk or fine worsted, checkered with various lively colors, two breadths

wide and three yards in length. It was brought over the head and made to

hide or discover the face, according to the occasion, or the wearer’s

fancy; it reached to the waist behind; one corner dropped as low as the

ankle on one side, and the other part, in folds hung down from the

opposite arm. The sleeves were of scarlet cloth, closed at the ends as

man’s vests, with gold lace round them, having plate buttons set with fine

stones. The head-dress was a fine kerchief of linen, straight about the

head. The plaid was tied before on the breast, with a buckle of silver or

brass, according to the quality of the person. The plaid was tied round

the waist with a belt of leather.

The Highlanders bore their part in

all of Scotland’s wars. An appeal, or order, to them never was made in

vain. Only a brief notice must here suffice. Almost at the very dawn of

Scotland’s history we find the inhabitants beyond the Grampians taking a

bold stand in behalf of their liberties. The Romans early triumphed over

England and the southern limits of Scotland. In the year 78 A. D.,

Agricola, an able and vigorous commander, was appointed over the forces in

Britain. During the years 80, 81, and 82, he subdued that part of Scotland

south of the friths of Forth and Clyde. Learning that a confederacy had

been formed to resist him at the north, during the summer of 83, he opened

the campaign beyond the friths. His movements did not escape the keen eyes

of the mountaineers, for in the night time they suddenly fell upon the

Ninth Legion at Loch Ore, and were only repulsed after a desperate

resistance. The Roman army receiving auxiliaries from the south, Agricola,

in the summer of 84, took up his line of march towards the Grampians. The

northern tribes, in the meantime, had united under a powerful leader whom

the Romans called Galgacus. They fully realized that their liberties were

in danger. They sent their wives and children into places of safety, and,

thirty thousand strong, waited the advance of the enemy. The two armies

came together at Mons Grampius. The field presented a dreadful

spectacle of carnage and destruction; for ten thousand of the tribesmen

fell in the engagement. The Roman army elated by its success passed the

night in exultation. The victory was barren of results, for, after three

years of persevering warfare, the Romans were forced to relinquish the

object of the expedition. In the year 183 the Highlanders broke through

the northern Roman wall. In 207 the irrepressible people again

broke over their limits, which brought the emperor Severus, although old

and in bad health, into the field. Exasperated by their resistance the

emperor sought to extirpate them because they had prevented his nation

from becoming the conquerors of Europe. Collecting a large body of troops

he directed them into the mountains, and marched from the wall of

Antoninus even to the very extremity of the island; but this year, 208,

was also barren of fruits. Fifty thousand Romans fell a prey to

fatigue, the climate, and the desultory assaults of the natives. Soon

after the entire country north of the Antonine wall, was given up, for it

was found that while it was necessary for one legion to keep the southern

parts in subjection two were required to repel the incursions of the Gael.

Incursions from the north again broke out during the year 306, when the

restless tribes were repelled by Constantius Chlorus. In the year they

were again repelled by Constans. During all these years the Highlanders

were learning the art of war by their contact with the Romans. They no

longer feared the invaders, for about the year 360, they advanced into the

Roman territories and committed many depredations. There was another

outbreak about the year 398. Finally, about the year 446, the Romans

abandoned Britain, and advised the inhabitants, who had suffered from the

northern tribes, to protect themselves by retiring behind and keeping in

repair the wall of Severus.

The people were gradually forming

for themselves distinct characteristics, as well as a separate kingdom

confined within the Grampian boundaries. This has been known as the

kingdom of the Scots; but to the Highlander as that of the Gael, or

Albanich. The epithets, Scots and English, are totally unknown in Gaelic.

They call the English Sassanachs, the Lowlanders are Gauls, and their own

country Gaeldach.

Passing over several centuries and

paying no attention to the rapines of the Danes and the Norse, we find

that the power of the Norwegians, under king Haco, was broken at the

battle of the Largs, fought October 2d, 1263 . King Alexander III.

summoned the Highlanders, who rallied to the defence of their Country and

rendered such assistance as was required. The right wing of the Scottish

army was composed of the men of Argyle, Lennox, Athole, and Galloway,

while the left wing was constituted by those from Fife, Stirling, Berwick,

and Lothian. The Center, commanded by the king in person, was composed of

the men of Ross, Perth, Angus, Mar, Mearns, Moray, Inverness, and

Caithness.

The conquest of Scotland, undertaken

by the English Edwards, culminated in the battle of Bannockhurn, fought

Monday, June 24, 1314, when the invaders met with a crushing

defeat, leaving thirty thousand of their number dead upon the field, or

two-thirds as many as there were Scots on the field. In this battle the

reserve, composed of the men of Argyle, Carrick, Kintyre, and the Isles,

formed the fourth line, was commanded by Bruce in person. The following

clans, commanded in person by their respective chiefs, had the

distinguished honor of fighting nobly: Stewart, Macdonald, Mackay,

Machintosh, Macpherson, Cameron, Sinclair Drummond, Campbell, Menzies,

Maclean, Sutherland, Robertson, Grant, Fraser, Macfarlane, Ross,

Macgregor, Munro, Mackenzie, and Macquarrie. or twenty-one in all.

In the year 1513, James IV.

determined on an invasion of England, and summoned the whole array of his

kingdom to meet him on the common moor of Edinburgh. One hundred thousand

men assembled in obedience to the command. This great host met the English

on the field of Flodden, September 9th. The right divisions of James’ army

were chiefly composed of Highlanders. The shock of the mountaineers, as

they poured upon the English pikemen, was terrible; but the force of the

onslaught once sustained became spent with its own violence. The

consequence was a total rout of the right wing accompanied by great

slaughter. Of this host there perished on the field fifteen lords and

chiefs of clans.

During the year 1547, the English,

under the duke of Somerset, invaded Scotland. The hostile armies came

together at Pinkie, September 18th. The right and left wings of the

Scottish army were composed of Highlanders. During the conflict the

Highlanders could not resist the temptation to plunder, and, while thus

engaged, saw the division of Angus falling back, though in good order;

mistaking this retrograde movement for a flight, they were suddenly seized

with a panic and ran off in all directions. Their terror was communicated

to other troops, who immediately threw away their arms and followed the

Highlanders. Everything was now lost; the ground over which the fight lay

was as thickly strewed with pikes as a floor with rushes; helmets,

bucklers, swords, daggers, and steel caps lay scattered on every side; and

the chase beginning at one o’clock, continued till six in the evening with

extraordinary slaughter.

During the reign of Charles I. civil

commotions broke out which shook the kingdom with great violence. The

Scots were courted by king and parliament alike. The Highlanders were

devoted to the royal government. In the year 1644 Montrose made a

diversion in the Highlands. With dazzling rapacity, at first only

supported by a handful of followers, but gathering numbers with success,

he erected the royal standard at Dumfries. The clans obeyed his summons,

and on September 1st, at Tippermuir, he defeated the Covenanters, and

again on the 12th at the Bridge of Dee. On February 2nd, 1645, at

Inverlochy, he crushed the Argyle Campbells, who had taken up the sword on

behalf of Cromwell. In rapid succession other victories were won at

Auldearn, Alford and Kilsyth. All Scotland now appeared to be recovered

for Charles, but the fruit of all these victories was lost by the defeat

at Philiphaugh, September 13th, 1645.

Within the brief space of three

years, James II., of England, succeeded in fanning the revolutionary

elements both in England and Scotland into a flame which he was powerless

to quench. The Highlanders chiefly adhered to the party of James which

received the name of Jacobites. Dundee hastened to the Highlands and

around him gathered the Highland chiefs at Lochabar. The army of William,

under Hugh Mackay, met the forces of Dundee at Killiecrankie, July 29th,

1689, where, under the spirited leadership of the latter, and the

irresistible torrent of the Highland charge, the forces of the former were

almost annihilated; but at the moment of victory Bonnie Dundee was killed

by a bullet. No one was left who was equal to the occasion, or who could

hold the clans together, and hence the victory was in reality a defeat.

The exiled Stuarts looked with a

longing eye to that crown which their stupid folly had forfeited. They

seemed fated to bring countless woes upon the loyal hearted, brave,

self-sacrificing Highlanders, and were ever eager to take advantage of any

circumstance that might lead to their restoration. The accession of George

I, in 1714, was an unhappy event for Great Britain. Discontent soon

pervaded the kingdom. All he appeared to care about was to secure for

himself and his family a high position, which he scarcely knew how to

occupy; to fill the pockets of his German attendants and his German

mistresses; to get away as often as possible from his uncongenial

islanders whose language he did not understand, and to use the strength of

Great Britain to obtain petty advantages for his German principality. At

once the new king exhibited violent predjuces against some of the chief

men of the nation, and irritated without a cause a large part of his

subjects. Some believed it was a favorable opportunity to reinstate the

Stuart dynasty. John Erskine, eleventh earl of Mar, stung by studied and

unprovoked insults, on the part of the king, proceeded to the Highlands

and placed himself at the head of the forces of the house of Stuart, or

Jacobites, as they were called. On September 6, 1715, Mar assembled at

Aboyne the noblemen, chiefs of clans, gentlemen, and others, with such

followers as could be brought together, and proclaimed James, king of

Great Britain. The insurrection, both in England and Scotland, began to

grow in popularity, and would have been a success had there been at the

head of affairs a strong military man. Nearly all the principal chiefs of

the clans were drawn into the movement. At Sheriffmuir, the contending

forces met, Sunday, November 13, 1715. The victory was with the

Highlanders, but Mar’s military talents were not equal to the occasion.

The army was finally disbanded at Aberdeen, in February, 1716.

The rebellion of 1745, headed by

prince Charles Stuart, was the grandest exhibition of chivalry, on the

part of the Highlanders, that the world has ever seen. They were actuated

by an exalted sense of devotion to that family, which for generations,

they had been taught should reign over them. At first victory crowned

their efforts, but all was lost on the disastrous field of Culloden,

fought April 16, 1746.

Were it possible it would be an unspeakable pleasure to

drop a veil over the scene, at the close of the battle of Culloden.

Language fails to depict the horrors that ensued. It is scarcely within

the bounds of belief that human beings could perpetrate such atrocities

upon the helpless, the feeble, and the innocent, without regard to sex or

age, as followed in the wake of the victors. Highland historians have made

the facts known. It must suffice here to give a moderate statement from an

English writer:

"Quarter was seldom given to the

stragglers and fugitives, except to a few considerately reserved for

public execution. No care or compassion was shown to their wounded; nay

more, on the following day most of these were put to death in cold blood,

with a cruelty such as never perhaps before or since has disgraced a

British army. Some were dragged from the thickets or cabins where they had

sought refuge, drawn out in line and shot, while others were dispatched by

the soldiers with the stocks of their muskets. One farm—building, into

which some twenty disabled Highlanders had crawled, was deliberately set

on fire the next day, and burnt with them to the ground. The native

prisoners were scarcely better treated; and even sufficient water was not

vouchsafed to their thirst. * * * * Every kind of havoc and outrage was

not only permitted, but, I fear, we must add, encouraged. Military license

usurped the place of law, and a fierce and exasperated soldiery were at

once judge—jury-—executioner. * * * * The rebels’ country was laid waste,

the houses plundered, the cabins burnt, the cattle driven away. The men

had fled to the mountains, but such as could be found were frequently

shot; nor was mercy always granted even to their helpless families. In

many cases the women and children, expelled from their homes and seeking

shelter in the clefts of the rocks, miserably perished of cold and hunger:

others were reduced to follow the track of the marauders, humbly imploring

for the blood and offal of their own cattle which had been slaughtered for

the soldiers’ food! Such is the avowal which historical justice demands.

But let me turn from further details of these painful and irritating

scenes, or of the ribald frolics and revelry with which they were

intermingled—races of naked women on horseback for the amusement of the

camp at Fort Augustus." [Lord Mahon’s "History of England," Vàl. III, pp.

308-311.]

The author and abettor of these

atrocities was the son of the reigning monarch.

Not satisfied with the destruction

which was carried into the very homes of this gallant, brave and generous

race of people, the British parliament, with a refined cruelty, passed an

act that, on and after August 1, 1747, any person, man, or boy, in

Scotland, who should on any pretense whatever wear any part of the

Highland garb, should be imprisoned not less than six months; and on

conviction of second offense, transportation abroad for seven years. The

soldiers had instructions to shoot upon the spot any one seen wearing the

Highland garb, and this as late as September, 1750. This law and other

laws made at the same time were unnecessarily severe.

However impartial or fair a

traveller may be his statements are not to be accepted without due

caution. He narrates that which most forcibly attracts his attention,

being ever careful to search out that which he desires. Yet, to a certain

extent, dependence must be placed in his observations. From certain

travellers are gleaned fearful pictures of the Highlanders during the

eighteenth century, written without a due consideration of the underlying

causes. The power of the chiefs had been weakened, while the law was still

impotent, many of them were in exile and their estates forfeited, and

landlords, in not a few instances, placed over the clansmen, who were

inimical to their best interests. As has been noticed, in 1746 the country

was ravaged and pitiless oppression followed. Destruction and misery

everywhere abounded. To judge a former condition of a people by their

present extremity affords a distorted view of the picture.

Fire and sword, war and rapine,

desolation and atrocity, perpetrated upon a high-spirited and generous

people, cannot conduce to the best moral condition. Left in poverty and

galled by outrage, wrongs will be resorted to which otherwise would be

foreign to a natural disposition. If the influences of a more refined age

had not penetrated the remote glens, then a rougher reprisal must be

expected. The coarseness, vice, rapacity, and inhumanity of the oppressor

must of necessity have a corresponding influence on their better natures.

If to this it be added that some of the chiefs were naturally fierce, the

origin of the sad features could readily be determined. Whatever vices

practiced or wrongs perpetrated, the example was set before them by their

more powerful and better conditioned neighbors. Among the crimes

enumerated is that some of the chiefs increased their scanty incomes by

kidnapping boys or men, whom they sold as slaves to the American planters.

If this be true, and in all probability it was, there must have been

confederates engaged in maritime pursuits. But they did not have far to go

for this lesson, for this nefarious trade was taught them, at their very

doors, by the merchants of Aberdeen, who were noted for a scandalous

system of decoying young boys from the country and selling them as slaves

to the planters in Virginia. It was a trade which in the early part of the

eighteenth century, was carried on to a considerable extent through the

Highlands; and a case which took place about 1742 attracted much notice a

few years later, when one of the victims having escaped from servitude,

returned to Aberdeen, and published a narrative of his sufferings,

seriously implicating some of the magistracy of the town. He was

prosecuted and condemned for libel by the local authorities, but the case

was afterwards carried to Edinburgh. The iniquitous system of kidnapping

was fully exposed, and the judges of the supreme court unanimously

reversed the verdict of the Aberdeen authorities and imposed a heavy fine

upon the provost, the four bailies, and the dean of guild. * * * An

atrocious case of this kind, which shows clearly the state of the

Highlands, occurred in 1739. Nearly one hundred men, women and children

were seized in the dead of night on the islands of Skye and Harris,

pinioned, horribly beaten, and stowed away in a ship bound for America, in

order to be sold to the planters. Fortunately the ship touched at

Donaghadee in Ireland, and the prisoners, after undergoing the most

frightful sufferings, succeeded in escaping. [ Lecky’s "History of

England," Vol. II, p. 274.]

Under existing circumstances it was

but natural that the more enterprising, and especially that intelligent

portion who had lost their heritable jurisdiction, should turn with

longing eyes to another country. America offered the most inviting asylum.

Although there was some emigration to America during the first half of the

eighteenth century, yet it did not fairly set in until about 1760. Between

the years 1763 and 1775 over twenty thousand Highlanders left their homes

to seek a better retreat in the forests of America. |