|

ON reaching the Doune a

great many changes at first perplexed us. The stables in front of the

house were gone, also the old barn, the poultry-house, the duck- pond;

every appurtenance of the old farmyard was removed to the new offices at

the back of the hill; a pretty lawn extended round two sides of the

house, and the backwater was gone, the broom island existed no longer,

no thickets of beech and alder intercepted the view of the Spey. A green

field dotted over with trees stretched from the broad terrace on which

the house now stood to the river, and the washing-shed was gone. All

that scene of fun was over, pots, tubs, baskets, and kettles were

removed with the maids and their attendants to a new building, always at

the back of the hill, better adapted, I daresay, to the purposes of a

regular laundry, but not near so picturesque, although quite as merry,

as our beloved broom island. I am sure I have backwoods tastes, like my

aunt Frere, whom I never could, by letter or in conversation, interest

in the Rothiemurchus improvements. She said the whole romance of the

place was gone. She prophesied, and truly, that with the progress of

knowledge all the old feudal affections would be overwhelmed,

individuality of character would cease, manners would change, the

Highlands would become like the rest of the world, all that made life

most charming there would fade away, little would be left of the olden

time, and life there would become as uninteresting as in other

little-remarkable places. The change had not begun yet, however. There

was plenty of all in the rough as yet in and about the Doune, where we

passed a very happy summer, for though just round the house were

alterations, all else was the same. The old servants were there, and the

old relations were there, and the lakes and the burnies, and the paths

through the forest, and we enjoyed our out-of-door life more this season

than usual, for cousin James Griffith arrived shortly after ourselves

with his sketch-book and paint-boxes, and he passed the greater part of

the day wandering through all that beautiful scenery, Jane and I his

constant companions. Mary was a mere baby, but William, Jane, and I, who

rode in turns on the grey pony, thought ourselves very big little

people, and expected quite as matter of right to belong to all the

excursion trains, were they large or small. Cousin James was fond of the

Lochans with their pretty fringe of birchwood, and the peeps through it

of the Croft, Tullochgrue, and the mountains. A sheep path running along

by the side of the burn which fed these picturesque small lochs was a

favourite walk of aunt Mary's, and my father had christened it by her

name. It started from the Polchar, and followed the water to the

entrance of the forest, where, above all, we loved to lose ourselves,

wandering on among the immense roots of the fir trees, and then

scattering to gather cranberries, while our artist companion made his

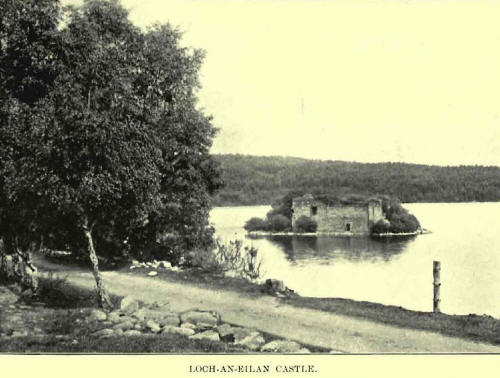

sketches. He liked best to draw the scenery round Loch-an-Eilan; he also

talked to us if we were near him, explaining the perspective and the

colouring and the lights and shadows, in a way we never forgot, and

which made these same scenes very dear to us afterwards. It was, indeed,

hardly possible to choose amiss; at every step there lay a picture. All

through the forest, which then measured in extent nearly twenty square

miles, small rivers ran with sometimes narrow strips of meadowland

beside them; many lochs of various sizes spread their tranquil waters

here and there in lonely beauty. In one of them, as its name implied,

was a small island quite covered by the ruins of a stronghold, a momento

of the days of the Bruce, for it was built by the Red Comyns, who then

owned all Strathspey and Badenoch. A low square tower at the end of the

ruin supported an eagle's nest. Often the birds rose as we were watching

their eyrie, and wheeled skimming over the loch in search of the food

required by the young eaglets, who could be seen peeping over the pile

of sticks that formed their home. Up towards the mountains the mass of

fir broke into straggling groups of trees at the entrance of the glens

which ran far up among the bare rocky crags of the Grampians. Here and

there upon the forest streams rude sawmills were constructed, where one

or at most two trees were cut up into planks at one time. The

sawmiller's hut close beside, a cleared field at hand with a slender

crop of oats growing on it, the peat- stack near the door, the cow, and

of course a pony, grazing at will among the wooding. Nearer to the Spey

the fir wood yielded to banks of lovely birch, the one small field

expanded into a farm; yet over all hung the wild charm of Nature,

mountain scenery in mountain solitude beautiful under any aspect of the

sky.

Our summer was less

crowded with company than usual, very few except connections or a

passing stranger coming to mar the sociability of the family party. Some

of the Gumming Gordons were with us, the Lady Logie, and Mrs Cooper,

with whom my mother held secret mysterious conferences. There were

Kinrara gaieties too, but we did not so frequently share in them, some

very coarse speeches of the Duchess of Manchester having too much

disgusted cousin James to make him care for such company too often

repeated. He had a very short time before been elected Head of his

college in Oxford. As Master of University with a certain position, a

good income, a fine house, and still better expectations through his

particular friends Lord Eldon the Chancellor, and his brother Sir

William Scott, he was now able to realise a long-cherished hope of

securing his cousin Mary to share his prosperous fortunes. They were

going together in middle age, very sensibly on both parts, first loves

on either side, fervent as they were, having been long forgotten, and

they were to be married and to be at home in Oxford by the gaudy day in

October. The marriage was to take place in the Episcopal chapel at

Inverness, and the whisperings with Mrs Cooper had reference to the

necessary arrangements. It was on the 19th of September, my brother

William's birthday, that the bridal party set out; a bleak day it was

for encountering Slochd Mor; that wild, lonely road could have hardly

looked more dreary. I accompanied the aunt I was so very much attached

to, in low enough spirits, having the thought of losing her for ever,

dreading many a trial she had saved me from, and Mrs Millar, who feared

her searching eye. My prospects individually were not brightened by the

happy event every one congratulated the family on. Cousin James was to

take his wife by the coast road to Edinburgh, and then to Tennochside.

Some other visits were to be paid by the way, so my aunt had packed the

newest portion of her wardrobe, much that she had been busied upon with

her own neat fingers all those summer days, and all her trinkets, in a

small trunk to take with her on the road; while her heavy boxes had

preceded us by Thomas Mathieson, the carrier, to Inverness, and were to

be sent on from thence by sea to London. We arrived at Grant's Hotel,

the carriage was unpacked, and no little trunk was forthcoming! It had

been very unwisely tied on behind, and had been cut off from under the

rumble by some exemplary Highlander in the dreary waste named from the

wild boors. My poor aunt's little treasures! for she was far from rich,

and had strained her scanty purse for her outfit. Time was short, too,

but my mother prevailed on a dressmaker—a Grant—to work. She contributed

of her own stores. The heavy trunks had luckily not sailed; they were

ransacked for linen, and on the 20th of September good Bishop Macfarlane

united as rationally happy a pair as ever undertook the chances of

matrimony together.

We all loved aunt Mary,

and soon had reason to regret her. Mrs Millar, with no eye over her,

ruled again, and as winter approached and we were more in the house,

nursery troubles were renewed. My father had to be frequently appealed

to, seventies were resumed. One day William was locked up in a small

room reserved for this pleasant purpose, the next day it was I, bread

and water the fare of both. A review of the volunteers seldom saw us all

collected on the ground, there was sure to be one naughty child in

prison and at home. We were flogged too for every error, boys and girls

alike, but my father permitted no one to strike us but himself. My

mother's occasional slaps and boxes on the ear were mere interjections

taken no notice of. It was upon this broken rule that I prepared a scene

to rid us of the horrid termagant, whom my mother with a gentle,

self-satisfied sigh announced to all her friends as such a treasure.

William was my accomplice, and this was our plan. My father's

dressing-closet was next to our sitting nursery, and he, with Raper

regularity, made use of it most methodically, dressing at certain stated

hours, continuing a certain almost fixed time at his toilet, very seldom

indeed deviating from this routine, which all in the same house were as

well aware of as we were, Mrs Millar among the rest. The nursery was

very quiet while he was our neighbour. It did sometimes happen, however,

that he ran up from his study to the dressing-room at unwonted hours,

and upon this chance our scheme was founded. William was to watch for

this opportunity; as soon as it occurred he secretly warned me, and I

immediately became naughty, did something that I knew would be

particularly disagreeable to Mrs Millar. She found fault pretty sharply,

I replied very pertly, in fact as saucily as I could, and no one could

do it better; this was followed as I expected by two or three hard slaps

on the back of my neck, upon which I set up a scream worthy of the rest

of the scene, so loud, so piercing, that in came my father to find me

crouching beneath the claws of a fury. "I have long suspected this,

Millar," said he, in the cold voice that sunk the heart of every

culprit, for the first tone uttered told them that their doom was

sealed. "Six weeks ago I warned you of what would be the consequences;

you can go and pack up your clothes without delay, in an hour you leave

this for Aviemore,"—and she did. No entreaties from my mother, no tears

from the three petted younger children, no excuses of any sort availed.

In an hour this odious woman had left us for ever. I can't remember her

wicked temper now without shuddering at all I went through under her

charge. In her character, though my father insisted on mentioning the

cause for which she was dismissed, my mother had gifted her with such a

catalogue of excellences, that the next time we heard of her she was

nurse to the young Duke of Roxburghe—that wonder long looked for, come

at last—and nearly murdered him one day, keeping him under water for

some childish fault till he was nearly drowned, quite insensible when

taken out by the footman who attended him. After this she was sent to a

lunatic asylum, where the poor creature ended her stormy days; her mind

had probably always been too unsettled to bear opposition, and we were

too old as well as too spirited to have been left so long at the mercy

of an ignorant woman, who was really a tender nurse to an infant then.

In some respects we were hardly as comfortable without her, the

good-natured Highland girl who replaced her not understanding the

neatnesses we had been accustomed to; and then I, like other patriots,

had to bear the blame of all these inconveniences; I, who for all our

sakes had borne these sharp slaps in order to secure our freedom, was

now complained of as the cause of very minor evils; my little brothers

and sisters, even William my associate, agreeing that my passionate

temper had aggravated "poor Millar," who had always been "very kind" to

them. Such ingratitude! "Kill the next tiger yourselves," said I, and

withdrew from their questionable society for half a day, by which time

Jane having referred to the story of the soldier and the Brahmin in our

Evenings at Home, and thought the matter over, made an oration which

restored outward harmony; inwardly, I remained a little longer angry—

another half-day--a long period in our estimate of time. My mother,

however, discovered that the gardener's young daughter would not do for

us undirected, so the coachman's wife, an English Anne, a very nice

person who had been nurse before she married, was raised from the

housemaid's place to be in Miliar's, and it being determined we were all

to stay over the winter in the Highlands, a very good plan was suggested

for our profitable management. We were certainly becoming not a little

wild as it was. It was arranged that a Miss Ramsay, an English girl from

Newcastle, who had been employed as a school teacher at Duthil, should

remove to the Doune, a happy change for her and a very fortunate hit for

us. She was a kind, cheerful creature, not capable of giving us much

accomplishment, but she gave us what we wanted more, habits of order.

The autumn and winter

passed very happily away, under these improved arrangements. The

following summer of 1809 was quite a gay one, a great deal of company

flocking both to the Doune and Kinrara, and at midsummer arrived William

; the little fellow, not quite eleven years old then, had travelled all

the way south after the summer holidays from Rothiemurchus to Eton, by

himself, paying his way like a man ; but they did not put his courage to

such a proof during the winter. He spent both his Christmas and his

Easter with the Freres, and so was doubly welcome to us in July. He took

care of himself as before on this long journey, starting with many

companions in a post-chaise, dropping his friends here and there as they

travelled, till it became more economical to coach it. At Perth all

coaching ended, and I don't remember how he could have got on from

thence to Dalwhinnie, where a carriage from the Doune was sent to meet

him.

During the winter my

father had been very much occupied with what we considered mere toys, a

little box full of soldiers, painted wooden figures, and tin flags

belonging to them, all which he twisted about over the table to certain

words of command, which he took the same opportunity of practising.

These represented our volunteers, about which, ever since I could

remember, my father, whilst in the Highlands, had been extremely

occupied. There was a Rothiemurchus company, his hobby, and an

Invereshie company, and I think a Strathspey company, but really I don't

know enough of warlike matters—though a Colonel's leddyto say whether

there could be as many as three. There were officers from all districts

certainly. My father was the Lieutenant-Colonel; Ballindalioch the

major; the captains, lieutenants, and ensigns were all Grants and

Macphersons, with the exception of our cousin Captain Cameron. Most of

the elders had served in the regular army, and had retired in middle

life upon their half-pay to little Highland farms in Strathspey and

Badenoch, by the names of which they were familiarly known as Sluggan,

Tullochgorm, Ballintomb, Kinchurdy, Bhealiott. Very soldierly they

looked in the drawing room in their uniforms, and very well the regiment

looked on the ground, the little active Highlander taking naturally to

the profession. There were fuglemen in those days, and I remember

hearing the inspecting general say that tall Murdoch Cameron the miller

was a superb model of a fugleman. I can see him now in his picturesque

dress, standing out in front of the lines, a head above the tallest,

directing the movements so accurately followed. My father on field days

rode a beautiful bay charger named Favourite, covered with goat-skins

and other finery, and seemingly quite proud of his housings. It was a

kilted regiment, and a fine set of smart well-set-up men they were, with

their plumed bonnets, dirks, and purses, and their low- heeled buckled

shoes. My father became his trappings well, and when, in early times, my

mother rode to the ground with him, dressed in a tartan petticoat, red

jacket gaudily laced, and just such a bonnet and feathers as he wore

himself, with the addition of a huge cairngorm on the side of it, the

old grey pony might have been proud in turn. These displays had,

however, long been given up. I recollect her always quietly in the

carriage with us bowing on all sides.

To prepare himself for

command, my father, as I have said, spent many a long evening

manoeuvring all his little figures; to some purpose, for his

Rothiemurchus men beat both Strathspey and Badenoch. I have heard my

uncle Lewis and Mr Cameron say there was little trouble in drilling the

men, they had their hearts in the work; and I have heard my father say

that the habits of cleanliness, and habits of order, and the sort of

waking up that accompanied it, had done more real good to the people

than could have been achieved by many years of less exciting progress.

So we owe Napoleon thanks. It was the terror of his expected invasion

that roused this patriotic fever amongst our mountains, where, in spite

of their distance from the coast, inaccessibility, and other advantages

of a hilly position, the alarm was so great that every preparation was

now in train for repelling the enemy. The men were to face the foe, the

women to fly for refuge to Castle Grant. My mother was all ready to

remove there, when the danger passed; but it was thought better to keep

up the volunteers. Accordingly they were periodically drilled,

exercised, and inspected till the year '13, if I remember rightly. It

was a very pretty sight, either on the moor of Tullochgorm or the

beautiful meadows of Dalnavert, to come suddenly on this fine body of

men and the gay crowd collected to look at them. Then their manuvres

with such exquisite scenery around them, and the hearty spirit of their

cheer whenever "the Leddy" appeared upon the ground; the bright sun

seldom shone upon a more exhilarating spectacle. The Laird, their

Colonel, reigned in all hearts. After the "Dismiss," bread and cheese

and whisky, sent forward in a cart for the purpose, were profusely

administered to the men, all of whom from Rothiemurchus formed a running

escort round our carriage, keeping up perfectly with the four horses in

hand, which were necessary to draw the heavy landau up and down the many

steeps of our hilly roads. The officers rode in a group round my father

to the Doune to dinner, and I recollect that it was in this year 1809

that my mother remarked that she saw some of them for the first time in

the drawing-room to tea—and sober.

Miss Ramsay occupied us

so completely this summer, we were much less with the autumn influx of

company than had been usual with us. Happy in the schoolroom, still

happier out in the forest, with a pony among us to ride and tie, and our

luncheon in a basket, we were indifferent to the more dignified parties

whom we sometimes crossed in our wanderings. To say the truth, my father

and mother did not understand the backwoods, they liked a very well

cooked dinner, with all suitable appurtenances in their own comfortable

house; neither of them could walk, she could not ride, there were no

roads for carriages, a cart was out of the question, such a vehicle as

would have answered the sort of expeditions they thus seldom went on was

never thought of, so with them it was a very melancholy attempt at the

elephant's dancing. Very different from the ways of Kinrara. There was a

boat on Loch-an-Eilan, which was regularly rowed over to the old ruined

castle, then to the pike bay to take up the floats that had fish to

them, and then back to the echo and into the carriage again ; but there

was no basket with luncheon, no ponies to ride and tie, no dreaming upon

the heather in pinafores all stained with blackberries! The little

people were a great deal merrier than their elders, and so some of

these, elders thought, for we were often joined by the "lags of the

drove," who perhaps purposely avoided the grander procession. Kinrara

was full as usual. The Duke of Manchester was there with some of his

children, the most beautiful statue-like, person that ever was seen in

flesh and blood. Poor Colonel Cadogan, afterwards killed in Spain, who

taught us to play the devil, which I wonder did not kill us; certainly

throwing that heavily-leaded bit of wood from one string to the

opposite, it might have fallen upon a head by the way, but it never did.

The Cummings of Altyre were always up in our country, some of them in

one house or the other, and a Mr Henville, an Oxford clergyman, Sir

William's tutor, who was in love with the beautiful Emilia, as was young

Charles Grant, now first seen among us, shy and plain and yet preferred;

and an Irish Mr Macklin, a clever little, flighty, ugly man, who played

the flute divinely, and wore out the patience of the laundry-maids by

the number of shirts he put on per day; for we washed for all our

guests, there was no one in all Rothiemurchus competent to earn a penny

in this way. He was a "very clean gentleman," and took a bath twice a

day, not in the river, but in a tub—a tub brought up from the

wash-house, for in those days the chamber apparatus for ablutions was

quite on the modern French scale. Grace Baillie was with us with all her

pelisses, dressing in all the finery she could muster, and in every

style; sometimes like a flower-girl, sometimes like Juno; now she was

queen-like, then Arcadian, then corps de ballet, the most amusing and

extraordinary figure stuck over with coloured glass ornaments, and by

way of being outrageously refined ; the most complete contrast to her

sister the Lady Logie. Well, Miss Baillie coming upstairs to dress for

dinner, opened the door to the left instead of the door to the right,

and came full upon short, fat, black Mr Macklin in his tub! Such a

commotion! we heard it in our schoolroom. Miss Baillie would not appear

at dinner. Mr Macklin, who was full of fun, would stay upstairs if she

did ; she insisted on his immediate departure, he insisted on their

swearing eternal friendship. Such a hubbub was never in a house before.

"If she'd been a young girl, one would almost forgive her nonsense,"

said Mrs Bird, the nurse. "If she had had common sense," said Miss

Ramsay, "she would have held her tongue; shut the door and held her

tongue, and no one would have been the wiser." We did not forget this

lesson in presence of mind, but no one having ventured on giving even an

idea of it to Miss Baillie, her adventure much annoyed the ladies, while

it furnished the gentlemen with an excuse for such roars of laughter as

might almost have brought down the ceiling of the dining-room.

Our particular friend,

Sir Robert Ainslie, was another who made a long stay with us. He brought

to my mother the first of those little red morocco cases full of needles

she had seen, where the papers were all arranged in sizes, on a slope,

which made it easy to select from them.

This was the first season

I can recollect seeing a family we all much liked, Colonel Gordon and

his tribe of fine sons. He brought them up to Glentromie in a boat set

on wheels, which after performing coach on the roads was used for

loch-fishing in the hills. He was a most agreeable and gentlemanly man,

full of amusing conversation, and always welcome to every house on the

way. He was said to be a careless father, and not a kind husband to his

very pretty wife, who certainly never accompanied him up to the Glen. He

was a natural son of the Duke of Gordon's, a great favourite with the

Duchess! much beloved by Lord Huntly whom he exceedingly resembled, and

so might have done better for himself and all belonging to him, had not

the Gordon brains been of the lightest with him. He was not so flighty,

however, as another visitor we always received for a few days, Lovat,

the Chief of the Clan Fraser, who was indeed a connection. The peerage

had been forfeited by the wicked lord in the last rebellion, the lands

and the chieftainship had been left with a cousin, the rightful heir,

who had sprung from the common stock before the attainder. He was an old

man, and his quiet, comfortable-looking wife was an old woman. They had

been at Cluny, the lady of the Macpherson chieftain being their niece,

or the laird their nephew, I don't exactly know which; and their

servants told ours they had had a hard matter to get their master away,

for he was subject to strange whims, and he had taken it into his head

when he was there that he was a turkey hen, and so he made a nest of

straw in his carriage and filled it with eggs and a large stone, and

there he sat hatching, never leaving his station but twice a day like

other fowl, and having his supplies of food brought to him. They had at

last to get Lady Cluny's henwife to watch a proper moment to throw out

all the eggs and to put some young chickens in their place, when Lovat,

satisfied he had accomplished his task, went about clucking and

strutting with wonderful pride in the midst of them. He was quite sane

in conversation generally, rather an agreeable man I heard them say, and

would be as steady as other people for a certain length of time; but

every now and then he took these strange fancies, when his wife had much

ado to bring him out of them. The fit was over when he came to us. It

was the year of the Jubilee when George III. had reigned his fifty

years. There had been great doings at Inverness, which this old man

described to us with considerable humour. His lady had brought away with

her some little ornaments prepared for the occasion, and kindly

distributed some of them among us. I long kept a silver buckle with his

Majesty's crowned head somewhere upon it, and an inscription

commemorating the event in pretty raised letters surrounding the

medallion. By the bye it was on the entrance of the old king upon his

fiftieth year of reign that the Jubilee was kept, in October I fancy

1809, for his state of health was such he was hardly expected to live to

complete it; that is, the world at large supposed him to be declining.

Those near his person must have known that it was the mind that was

diseased, not the strong body, which lasted many a long year after this,

though every now and then his death was expected, probably desired, for

he had ceased to be a popular sovereign. John Bull respected the decorum

of his domestic life, and the ministerial Tory party of course made the

best of him. All we of this day can say of him is, that he was a better

man than his son, though, at the period I am writing of, the Whigs,

among whom I was reared, were very far indeed from believing in this

truism.

It was this autumn that a

very great pleasure was given to me. I was taken on a tour of visits

with my father and mother. We went first to Inverness, where my father

had business with his agent, Mr Cooper. None of the lairds in our north

countrie managed their own affairs, all were in the hands of some little

writer body, who to judge by consequences ruined most of their clients.

One of these leeches generally sufficed for ordinary victims. My dear

father was preyed on by two or three, of which fraternity Mr Arthur

Cooper was one. He had married Miss Jenny and made her a very indulgent

husband; her few hundreds and the connection might have been her

principal attractions, but once attracted, she retained her power over

him to the end. She was plain but ladylike, she had very pretty, gentle

manners, a pleasing figure, beautiful hand, dressed neatly, kept a very

comfortable house, and possessed a clear judgment, with high principles

and a few follies; a little absurd pride, given her perhaps by my

great-aunt, the Lady Logie, who had brought her up and was very fond of

her. We were all very fond of Mrs Cooper, and she adored my father.

While we were at Inverness we paid some morning visits too

characteristic of the Highlands to be omitted in this true chronicle of

the times; they were all in the Clan. One was to the Misses Grant of

Kinchurdy, who were much patronised by all of their name, although they

had rather scandalised some of their relations by setting up as

dressmakers in the county town. Their taste was not perfect, and their

skill was not great, yet they prospered. Many a comfort earned by their

busy needles found its way to the fireside of the retired officer their

father, and their helping pounds bought the active officer, their

brother, his majority. We next called on Mrs Grant, late of Aviemore,

and her daughters, who had set up a school, no disparagement to the

family of an innkeeper although the blood they owned was gentle, and

last we took luncheon with my great-aunt, the Lady Glenmoriston, a

handsome old lady with great remains of shrewdness in her countenance. I

thought her cakes and custards excellent; my mother, who had seen them

all come out of a cupboard in the bedroom, found her appetite fail her

that morning. Not long before we had heard of her grandson our cousin

Patrick's death, the eldest of my father's wards, the Laird; she did not

appear to feel the loss, yet she did not long survive him. A clever

wife, as they say in the Highlands, she was in her worldly way. I did

not take a fancy to her.

We left Inverness nothing

loth, Mrs Cooper's small house in the narrow, dull street of that little

town not suiting my ideas of liberty; and we proceeded in the open

barouche and four to call at Nairn upon our way to Forres. At Nairn,

comfortless dreary Nairn, where no tree ever grew, we went to see a

sister of Logie's, a cousin, a Mrs Baillie, some of whose sons had found

31 Lincoln's Inn Fields a pleasant resting-place on the road to India.

Her stepson—for she was a second wife —the great Colonel Baillie of

Bundelcund and of Leys, often in his pomposity, when I knew him

afterwards, recalled to my mind the very bare plenishing of this really

nice old lady. The small, cold house chilled our first feelings. The

empty room, uncurtained, half carpeted, with a few heavy chairs stuck

formally against the walls, and one dark-coloured, well-polished table

set before the fireplace, repressed all my gay spirits. It took a great

deal of bread and marmalade, scones and currant wine, and all the kind

welcome of the little, brisk old lady to restore them; not till she

brought out her knitting did I feel at home—a hint remembered with

profit. Leaving this odious fisher place very near as quick as King

James did, we travelled on to dine at five o'clock at Burgie, a small,

shapeless square of a house, about two miles beyond Forres, one of the

prettiest of village towns, taking situation into the account. There is

a low hill with a ruin on it, round which the few streets have

clustered; trees and fields are near, wooded knolls not far distant,

gentlemen's dwellings peep up here and there; the Moray Firth, the town

and Sutors of Cromartie, and the Ross-shire hills in the distance;

between the village and the sea extends a rich flat of meadowland,

through which the Findhorn flows, and where stand the ruins of the

ancient Abbey of Kinloss, my father's late purchase. I don't know why

all this scene impressed me more than did the beautiful situation of

Inverness. In after-years I did not fail in admiration of our northern

capital, but at this period I cannot remember any feeling about

Inverness except the pleasure of getting out of it, while at Forres all

the impressions were vivid because agreeable; that is I, the perceiver,

was in a fitting frame of mind for perceiving. How many travellers, ay,

thinkers, judges, should we sift in this way, to get at the truth of

their relations. On a bilious day authors must write tragically.

The old family of Dunbar

of Burgie, said to be descended from Randolph, Earl of Moray—though all

the links of the chain of connection were far from being forthcoming—had

dwindled down rather before our day to somebody nearly as small as a

bonnet Laird; his far-away collateral heir, who must have been a most

ungainly lad, judging from his extraordinary appearance in middle age,

had gone out to the West Indies to better his fortunes, returning to

take possession of his inheritance a little before my father's marriage.

In figure something the shape of one of his own sugar hogsheads, with

two short thick feet standing out below, and a round head settled on the

top like a picture in the Penny Magazine of one of the old English

punishments, and a countenance utterly indescribable— all cheek and chin

and mouth, without half the proper quantity of teeth; dressed too like a

mountebank in a light blue silk embroidered waistcoat and buff satin

breeches, and this in Pitt and Fox days, when the dark blue coat, and

the red or the buff waistcoat, according to the wearer's party, were

indispensable. So dressed, Mr Dunbar presented himself to my father, to

be introduced by him to an Edinburgh assembly. My father, always fine,

then a beau, and to the last very nervous under ridicule! But Burgie was

a worthy man, honest and upright and kind-hearted, modest as well, for

he never fancied his own merits had won him his wealthy bride; their

estates joined, "and that," as he said himself, "was the happy

coincidence." The Lady Burgie and her elder sister, Miss Brodie of

Lethen, were co-heiresses. Coulmonie, a very picturesque little property

on the Findhorn, was the principal possession of the younger when she

gave her hand to her neighbour, but as Miss Brodie never married, all

their wide lands were united for many a year to the names and titles of

the three contracting parties, and held by Mr and Mrs Dunbar Brodie of

Burgie, Lethen, and Coulmonie during their long reign of dulness

precedence being given to the gentleman after some consideration. They

lived neither at very pretty Coulmonie, nor at very comfortable Lethen,

nor even in the remains of the fine old Castle of Burgie, one tall tower

of which rose from among the trees that sheltered its surrounding

garden, and served only as storehouse and toolhouse for that department;

they built for themselves the tea-canister-like lodge we found them in,

and placed it far from tree or shrub, or any object but the bare moor of

Macbeth's witches. My spare time at this romantic residence was spent

mostly in the tower, there being up at the top of it an apple-room,

where some little maiden belonging to the household was occupied in

wiping the apples and laying them on the floor in a bed of sand. In this

room was a large chest, made of oak with massive hasps, several

padlocks, and a chain; very heavy, very grand-looking, indeed awful,

from its being so alone, so secured, and so mysteriously hidden as it

were. It played its part in after-years, when all that it did and all

that was done to it shall take the proper place in these my memoirs, if

I live to get so far on in my chroniclings. At this time I was afraid

even to allude to it, there appeared to be something so supernatural

about the look of it.

Of course we had several

visits to pay from Burgie. In the town of Forres we had to see old Mrs

Provost Grant and her daughters, Miss Jean and Miss—I forget what—but

she, the nameless one, died. Miss Jean, always called in those parts

Miss Jean Pro, because her mother was the widow of the late Provost, was

the living frontispiece to the 'world of fashion." A plain, ungainly,

middle-aged woman, with good Scotch sense when it was wanted, occupied

every waking hour in copying the new modes in dress; no change was too

absurd for Miss Jean's imitation, and her task was not a light one, her

poor purse being scanty, and the Forres shops, besides being dear, were

ill supplied. My mother, very unwisely, had told me her appearance would

surprise me, and that I must be upon my guard and show my good breeding

by looking as little at this figure of fun as if she were like other

people; and my father repeated the story of the Duchess of Gordon, who

received at dinner at Kinrara some poor dominie, never before in such a

presence; he answered all her civil inquiries thus, "'Deed no, my Lady

Duchess; my Lady Duchess, 'deed yes," she looking all the while exactly

as if she had never been otherwise addressed—not even a side smile to

the amused circle around her, lest she might have wounded the good man's

feelings. I always liked that story, and thought of it often before and

since, and had it well on my mind on this occasion; but it did not

prevent my long gaze of surprise at Miss Pro. In fact, no one could have

avoided opening wide eyes at the caricature of the modes she exhibited;

she was fine, too, very fine, mincing her words to make them English,

and too good to be laughed at, which somehow made it the more difficult

not to laugh at her. In the early days, when her father, besides his

little shop, only kept the post-office in Forres, she, the eldest of a

whole troop of bairns, did her part well in the humble household,

helping her mother in her many cares, and to good purpose; for of the

five clever sons who out of this rude culture grew up to honour in every

profession they made choice of, three returned "belted knights" to lay

their laurels at the feet of their old mother; not in the same poor but

and ben in which she reared them; they took care to shelter her age in a

comfortable house, with a drawing-room upstairs, where we found the

family party assembled, a rather ladylike widow of the eldest son (a

Bengal civilian) forming one of it. Mrs Pro was well born of the

Arndilly Grants, and very proud she was of her lineage, though she had

made none the worse wife to the honest man she married for his failure

in this particular. In manners she could not have been his superior, the

story going that in her working days she called out loud, about the

first thing in the morning, to the servant lass to "put on the parritch

for the pigs and the bairns," the pigs as most useful coming first.

From Burgie we went back

a few miles to Moy, an old-fashioned house, very warm and very

comfortable, and very plentiful, quite a contrast, where lived a distant

connection, an old Colonel Grant, a cousin of Glenmoriston's, with a

very queer wife, whom he had brought home from the Cape of Good Hope.

This old man, unfortunately for me, always breakfasted upon porridge; my

mother, who had particular reasons for wishing to make herself agreeable

to him, informed him I always did the same, so during the three days of

this otherwise pleasant visit a little plate of porridge for me was

placed next to the big plate of porridge for him, and I had to help

myself to it in silent sadness, for I much disliked this kind of food as

it never agreed with me, and though at Moy they gave me cream with it, I

found it made me just as sick and heavy afterwards as when I had the

skimmed milk at home. They were kind old people these in their homely

way.

From Moy we went straight

to Elgin, where I remember only the immense library belonging to the

shop of Mr Grant the bookseller, and the ruins of the fine old

Cathedral. We got to Duffus to dinner, and remained there a few days

with Sir Archibald and Lady Dunbar and their tribe of children. Lady

Dunbar was one of the Cummings of Altyre—one of a dozen--and she had

about a dozen herself, all the girls handsome. The house was very full.

We went upon expeditions every morning, danced all the evenings, the

children forming quite a part of the general company, and as some of the

Altyre sisters were there, I felt perfectly at home. Ellen and Margaret

Dunbar wore sashes with their white frocks, and had each a pair of silk

stockings which they drew on for full dress, a style that much surprised

me, as I, at home or abroad, had only my pink gingham frocks for the

morning, white calico for the afternoon, cotton stockings at all times,

and not a ribbon, a curl, or an ornament about me.

One day we drove to

Gordonstown, an extraordinary palace of a house lately descended to Sir

William, along with a large property, where he had to add the Southron

Gordon to the Wolf of Badenoch's long-famed name, not that it is quite

clear that the failing clan owes allegiance to this branch particularly,

but there being no other claimant Altyre passes for the Comyn Chief. His

name is on the roll of the victors at Bannockburn as a chieftain

undoubtedly. I wonder what can have been done with Gordonstown. It was

like the side of a square in a town for extent of façade, and had

remains of rich furnishings in it, piled up in the large deserted rooms,

a delightful bit of romance to the young Dunbars and me. Another day we

went greyhound coursing along the fine bold cliffs near Peterhead, and

in a house on some bleak point or other we called on a gentleman and his

sister, who showed us coins, vases, and spear-heads found on excavating

for some purpose in their close neighbourhood at Burghead, all Roman; on

going lower the workmen came upon a bath, a spring enclosed by cut-stone

walls, a mosaic pavement surrounding the bath, steps descending to it,

and paintings on the walls. The place was known to have been a Roman

station with many others along the south side of the Moray Firth. We had

all of us great pleasure in going to see these curious remains of past

ages thus suddenly brought to light. I remember it all perfectly as if I

had visited it quite lately, and I recollect regretting that the walls

were in many parts defaced.

On leaving Duffus we

drove on to Garmouth to see Mr Steenson, my father's wood agent there;

he had charge of all the timber floated down the Spey from the forest of

Rothiemurchus where it had grown for ages, to the shore near Fochabers

where it was sorted and stacked for sale. There was a good-natured wife

who made me a present of a milk-jug in the form of a cow, which did duty

at our nursery feasts for a wonderful while, considering it was made of

crockery ware; and rather a pretty daughter, just come from the

finishing school at Elgin, and stiff and shy of course. These ladies

interested me much less than did the timber-yard, where all my old

friends the logs, the spars, and the deals and my mother's oars were

piled in such quantities as appeared to me endless. The great width of

the Spey, the bridge at Fochabers, and the peep of the towers of Gordon

Castle from amongst the cluster of trees that concealed the rest of the

building, all return to me now as a picture of beauty. The Duke lived

very disreputably in this solitude, for he was very little noticed, and,

I believe, preferred seclusion.

It was late when we

reached Leitchison, a large wandering house in a flat bare part of the

country, which the Duke had given, with a good farm attached, to his

natural son Colonel Gordon, our Glentromie friend. Bright fires were

blazing in all the large rooms, to which long passages led, and all the

merry children were jumping about the hail anxiously waiting for us.

There were five or six fine boys, and one daughter, Jane, named after

the Duchess. Mrs Gordon and her two sisters, the dark beautiful Agnes,

and fat, red-haired Charlotte, were respectably connected in Elgin, had

money, were well educated and so popular women. Mrs Gordon was pretty

and pleasing, and the Colonel in company delightful; but somehow they

did not get on harmoniously together; he was eccentric and extravagant,

she peevish, and so they lived very much asunder. I did not at all

approve of the ways of the house after Duffus, where big and little

people all associated in the family arrangements. Here at Leitchison the

children were quite by themselves, with porridge breakfasts and broth

dinners, and very cross Charlotte Ross to keep us in order. If she tried

her authority on the Colonel as well, it was no wonder if he preferred

the Highlands without her to the Lowlands with her, for I know I was not

sorry when the four bays turned their heads westward, and, after a

pleasant day's drive, on our return through Fochabers, Elgin, and Forres,

again stopped at the door at Logie.

Beautiful Logie! a few

miles up the Findhorn, on the wooded banks of that dashing river, wooded

with beech and elm and oak centuries old; a grassy holm on which the

hideous house stood, sloping hills behind, the water beneath, the

Darnaway woods beyond, and such a garden! such an orchard! well did we

know the Logie pears, large hampers of them had often found their way to

the Doune; but the Logie guignes could only be tasted at the foot of the

trees, and did not my young cousins and I help ourselves! Logie himself,

my father's first cousin, was a tall, fine-looking man, with a very ugly

Scotch face, sandy hair and huge mouth, ungainly in manner yet kindly,

very simple in character, in fact a sort of goose; much liked for his

hospitable ways, respected for his old Cumming blood (he was closely

related to Altyre), and admired for one accomplishment, his playing on

the violin. He had married rather late in life one of the cleverest

women of the age, an Ayrshire Miss Baillie, a beauty in her youth, for

she was Burns' "Bonnie Leslie," and a bit of a fortune, and she gave

herself to the militia captain before she had ever seen the Findhorn!

and they were very happy. He looked up to her without being afraid of

her, for she gave herself no superior wisdom airs, indeed she set out so

heartily on St Paul's advice to be subject to her husband, that she

actually got into a habit of thinking he had judgment; and my mother

remembered a whole room full of people hardly able to keep their

countenances, when she, giving her opinion on some disputed matter,

clenched the argument as she supposed, by adding, "It's not my

conviction only, but Mr Cumming says so." She was too Southron to call

the Laird "Logic." Logic banks and Logic braes! how very lovely ye were

on those bright autumn days, when wandering through the beech woods upon

the rocky banks of the Findhorn, we passed hours, my young cousins and

I, out in the pure air, unchecked of any one. Five sons and one fair

daughter the Lady Logic bore her Laird; they were not all born at the

time I write of. Poor Alexander and Robert, the two eldest, fine

handsome boys, were my companions in these happy days; long since

mourned for in their early graves. There was a strange mixture of the

father's simplicity and the mother's shrewdness in all the children, and

the same in their looks; only two were regularly handsome, May Anne and

Alexander, who was his mother's darling. Clever as she was she made far

too much distinction between him and the rest; he was better dressed,

better fed, more considered in every way than the younger ones, and yet

not spoiled. He never assumed and they never envied, it was natural that

the young Laird should be most considered. A tutor, very little older

than themselves, and hardly as well dressed, though plaiding was the

wear of all, taught the boys their humanities ; he ate his porridge at

the side-table with them, declining the after-cup of tea, which

Alexander alone went to the state-table to receive. At dinner it was the

same system still, broth and boiled mutton, or the kain fowl at the poor

tutor's side-table. Yet he revered the Lady; everybody did; every one

obeyed her without a word, or even, I believe, a thought, that it was

possible her orders could be incorrect. Her manner was very kind, very

simple, though she had an affected way of speaking; but it was her

strong sense, her truthful honesty, her courage—moral courage, for the

body's was weak enough—her wit, her fire, her readiness that made her

the queen of the intellect of the north countrie. Every one referred to

her in their difficulties; it was well that no winds wandered over the

reeds that grew by the side of the Lady Logie. Yet she was worldly in a

degree, no one ever more truly counselled for the times, or lived more

truly up to the times, but so as it was no reproach to her. She was with

us often at the Doune with or without the Laird, Alexander sometimes her

companion, and he would be left with us while she was over at Kinrara,

where she was a great favourite. I believe it was intended by the family

to marry Alexander to Mary, they were very like and of suitable ages,

and he was next heir of entail presumptive to Rothiemurchus after my

brothers. It had also been settled to marry first Sir William Cumming

and afterwards Charles, to me. Jane oddly enough was let alone, though

we always understood her to be the favourite with everybody.

My father had a story of

Mrs Cumming that often has come into my head since. He put her in mind

of it now, when she declined going on in the carriage with him and my

mother to dine at Relugas, where we were to remain for a few days. She

had no great faith in four-in-hands on Highland roads, at our English

coachman's rate of driving. She determined on walking that lovely mile

by the river-side, with Alexander and the "girlie "—me—as her escort;

her dress during the whole of our visit, morning, noon, and night, was a

scarlet cloth gown made in habit fashion, only without a train, braided

in black upon the breast and cuffs, and on her head a black velvet cap,

smartly set on one side, bound with scarlet cord, and having a long

scarlet tassel, which dangled merrily enough now, as my father reminded

her of what he called the "Passage of the Spey." It seemed that upon one

occasion when she was on a visit to us, they were all going together to

dine at Kinrara, and as was usual with them then, before the ford at our

offices was settled enough to use when the water was high, or the road

made passable for a heavy carriage up the bank of the boyack, they were

to cross the Spey at the ford below Kinapol close to Kinrara. The river

had risen very much after heavy rain in the hills, and the ford, never

shallow, was now so deep that the water was up above the small front

wheels and in under the doors, flooding the footboard. My mother sat

still and screamed. Mrs Cumming doubled herself up orientally upon the

seat, and in a commanding voice, though pale with terror, desired the

coachman, who could not hear her, to turn. On plunged the horses, in

rushed more water, both ladies shrieked. My father attempted the

masculine consolation of appealing to their sense of eyesight, which

would show them "returning were as tedious as going o'er," that the next

step must be into the shallows. The Lady Logie turned her head

indignantly, her body she could not move, and from her divan-like seat

she thus in tragic tones replied—"A reasonable man like you,

Rothiemurchus, to attempt to appeal to the judgment of a woman while

under the dominion of the passion of fear!"

At Relugas lived an old

Mrs Cuming, with one m, the widow of I don't know whom, her only child

her heiress daughter, and the daughter's husband, Tom Lauder. He had

some income from his father, was to have more when his father died, and

a large inheritance with a baronetcy at an uncle's death, Lord

Fountainhall. It had been a common small Scotch house, but an Italian

front had been thrown before the old building, an Italian tower had been

raised above the offices, and with neatly kept grounds it was about the

prettiest place ever lived in. The situation was beautiful, on a high

tongue of land between the Divie and the Findhorn—the wild, leaping,

rocky-bedded Divie and the broader and rapid Findhorn. All along the

banks of both were well-directed paths among the wooding, a group of

children flitting about the heathery braes, and the heartiest, merriest

welcome within. Mr and Mrs Lauder were little more than children

themselves, in manner at least; really young in years and gifted with

almost bewildering animal spirits, they did keep up a racket at Relugas!

It was one eternal carnival: up late, a plentiful Scotch breakfast, out

all day, a dinner of many courses, mumming all the evening, and a supper

at the end to please the old lady. A Colonel Somebody had a story—ages

after this, however—that having received an appointment to India, he

went to take leave of his kind friends at Relugas. It was in the

evening, and instead of finding a quiet party at tea, he got into a

crowd of popes, cardinals, jugglers, gipsies, minstrels, flower-girls,

etc., the usual amusements of the family. He spent half a lifetime in

the East, and returning to his native place thought he would not pass

that same hospitable door. He felt as in a dream, or as if his years of

military service had been a dream— there was all the crowd of

mountebanks again! The only difference was In the actors; children had

grown up to take the places of the elders, some children, for all the

elders were not gone. Sir Thomas Dick Lauder wore as full a turban, made

as much noise, and was just as thin as the Tom Lauder of twenty years

before, and his good lady, equally travestied and a little stouter, did

not look a day older with her grownup daughters round her, than she did

in her own girlish times. It was certainly a pleasant house for young

people. Sir Thomas, with all his frivolity, was a very accomplished man;

his taste was excellent, as all his improvements showed; no walks could

have been better conducted, no trees better placed, no views better

chosen, and this refinement was carried all through, to the colours of

the furniture and the arrangement of It. He drew well, sketched very

accurately from nature, was clever at puzzles, bouts-rimés, etc.—the

very man for a country neighbourhood. Her merit was in implicitly

following his lead; she thought, felt, saw, heard as he did, and if his

perceptions altered or varied, so did hers. There never was such a

patient Grizzel; and the curious part of their history was that being

early destined by their parents to go together, they detested one

another, as children did nothing but quarrel, agreed no better as they

grew, being at one on one only point, that they never would marry. How

to avoid such •a catastrophe was the single subject they discussed

amicably. They grew confidential upon it quite, and it ended in their

settlement at Relugas.

This merry visit ended

our tour. We drove home in a few hours over the long, dreary moor

between the Spey and the Findhorn, passing one of the old strongholds of

the Grants, the remains of a square tower beside a lonely lake—a very

lonely lake, for not a tree nor a shrub was near it; and resting the

horses at the Bridge of Carr, a single arch over the Dulnain, near which

had clustered a few cottages, a little inn amongst them sheltered by

trees; altogether a bit of beauty in the desert. I had been so good all

this tour, well amused, made of, and not worried, that Miss Ramsay was

extremely complimented on the improvement she had effected in my

naturally bad disposition. As if there were any naturally bad

dispositions! Don't we crook them, and stunt them, and force them, and

break them, and do everything in the world except let them alone to

expand in pure air to the sun, and nourish them healthfully?

We were now to prepare

for a journey to London. I recollect rather a tearful parting from a

companion to whom we had become much attached, Mr Peter of Duthil's

youngest son—or only son, for all I know, as I never saw any other.

Willie Grant was a fine handsome boy, a favourite with everybody and the

darling of his poor father, who had but this bright spot to cheer his

dull home horizon. All this summer Willie had come to the Doune with the

parson every third Sunday; that is, they came on the Saturday, and

generally remained over Monday. He was older than any of us, but not too

old to share all our out-of-door fun, and he was full of all good,

really and truly sterling. We were to love one another for ever, yet we

never met again. When we returned to the Highlands he was in the East

India Military College, and then he sailed, and though he lived to come

home, marry, and settle in the Highlands, neither Jane nor I ever saw

him more. How many of these fine lads did my father and Charles Grant

send out to India! Some that throve, some that only passed, some that

made a name we were all proud of, and not one that I heard of that

disgraced the homely rearing of their humbly-positioned but gentle-born

parents. The moral training of those simple times bore its fair fruits:

the history of many great men in the last age began in a cabin. Sir

Charles Forbes was the son of a small farmer in Aberdeenshire. Sir

William Grant, the Master of the Rolls, was a mere peasant—his uncles

floated my father's timber down the Spey as long as they had strength to

follow the calling. General William Grant was a footboy in my uncle

Rothie's family. Sir Coiquhoun Grant, though a woodsetter's child, was

but poorly reared, in the same fashion as Mrs Pro's fortunate boys. Sir

William Macgregor, whose history was most romantic of all, was such

another. The list could be easily lengthened did my memory serve, but

these were among the most striking examples of what the good plain

schooling of the dominie, the principles and the pride of the parents,

produced in young ardent spirits; forming characters which, however they

were acted on by the world, never forgot home feelings, although they

proved this differently. The Master of the Rolls, for instance, left all

his relations in obscurity. A small annuity rendered his parents merely

independent of hard labour; very moderate portions just secured for his

sisters decent matches in their own degree; an occasional remittance in

a bad season helped an uncle or a brother out of a difficulty. I never

heard of his going to see them, or bringing any of them out of their own

sphere to visit him. While the General shoved on his brothers, educated

his nephews and nieces, pushed the boys up, married the girls well—such

as had a wish to raise themselves—and almost resented the folly of Peter

the Pensioner, who would not part with one of his flock from the very

humble home where he chose to keep them. Which plan was wisest, or was

either quite right? Which relations were happiest—those whose feelings

were sometimes hurt, or those whose frames were sometimes over-wearied

and but scantily refreshed? I often pondered in my own young mind over

these and similar questions; but just at the time of our last journey

from the Doune to London less puzzling matters principally occupied my

sister Jane and me.

We were not sure whether

or no Miss Ramsay were to remain with us; neither were we sure whether

or no we wished it. We should have more of our own way without her, that

was certain; but whether that would be so good for us, whether we should

get on as well in all points by ourselves, we were beginning to be

suspicious of. She had taught us the value of constant employment,

regular habits, obliging manners, and we knew, though we did not allow

it, that there would be less peace as well as less industry should we be

again left to govern ourselves. However, so it was settled. Miss Ramsay

was dropped at Newcastle amongst her own friends, and for the time the

relief from restraint seemed most agreeable. |