|

I HAVE always looked on my

appearance at the Inverness Meeting as the second era in my life,

although at the time I was hardly aware of it. Our removal to the

Highlands, our regular break-in under the governess, the partial opening

of young minds, had all gone on in company with Jane, who was in many

respects more of a woman than I who was by three years her elder. I was

now to be alone, my occupations, habits, ideas were all to be different

from, indeed repudiated by, the schoolroom. Miss Elphick thought me—and

she was right—a year too young for the trials awaiting me, for which I

was in no way prepared. She was annoyed at not having been consulted as

to the fitness of her pupil for commencing life on her own account, and

so she would neither help my inexperience nor allow me to take shelter

under my usual employments.

I felt very lonely

wandering about by myself, or seated in state in the library, with no

one to speak to. My mother was little with me, her hours were late, her

habits indolent; besides, she was busily engaged with my father

revolving several serious projects for the good of the family, none of

them proper for us to be acquainted with till they were decided on.

My father's Scotch

friends were anxious that he should return to their Bar, and the state

of his affairs, though none of us young people knew it, rendered some

such step necessary. Also my brother William had to look for a home

while he remained in college. Mrs Gordon had had another baby, and in

her small house there was no longer room for a lodger. Then there was

the beautiful daughter! The pale thin girl had blossomed into beauty,

and hopes were raised of the consequences of her being seen beyond the

wilderness she had hitherto bloomed in.

So Edinburgh was decided

on, and Grace Baillie was written to, to engage us a house.

When we went to take

leave of Mr Cameron, he followed us down to the gate at the Lochan Mor;

and there laying a hand on each young head, he bade God bless us with a

fervour we recollected afterwards, and felt that he must have considered

it as a final parting. Then wrapping his plaid round him and drawing his

bonnet down over his eyes, he turned and moved away through the birch

wood. He died during the winter, upwards of seventy-eight, young for a

Highlander. Rothiemurchus altered after all that old set were gone.

We were in great glee

over our preparations for Edinburgh, when one night we got a fright; one

of the chimneys in the old part of the house took fire, a common

occurrence-it was the way they were frequently cleaned! but on this

occasion -the flames communicated some sparks to a beam in the nearest

ceiling, and soon part of the roof was in flames. None of us being in

bed the house was soon roused, the masons sent for, and a plentiful

supply of water being at hand all danger was soon over. My mother was

exceedingly frightened, could not be persuaded to retire to her room,

and kept us all near her to be ready for whatever might befall. At last,

when calmer, we missed Miss Elphick; she was not to be found, and we

feared some mischance had happened to her. After a good search she was

discovered as far from the house as she could well get, dancing about on

the lawn in her night-dress, without a shoe or a stocking on her; by

which crazy proceeding she caught so severe a cold as was nearly the

death of her. Jane said the whole scene made a beautiful picture, and

while the rest of us were trembling for the fate of the poor old house,

she was admiring the various groups as they moved about in the

flickering light of the blazing chimney.

We had no more adventures

before we started on our journey, nor any incidents deserving of notice

during our three days' travel, save indeed one, the most splendid bow

from my odious partner, who, from the top of the Perth coach as it

passed us, almost prostrated himself before the barouche. It was cold

wretched weather, snow on the hills, :frost in the plains, a fog over

the ferry. We were none of us sorry to find ourselves within the warm

cheerful house that Miss Baillie had taken for us, No. 4 Heriot Row. The

situation was pleasant, though not at all what it is now. There were no

prettily laid-out gardens then between Heriot Row and Queen Street, only

a long strip of unsightly grass, a green, fenced by an untidy wall and

abandoned to the use of the washerwomen. It was an ugly prospect, and we

were daily indulged with it, the cleanliness of the inhabitants being so

excessive that, except on Sundays and "Saturdays at e'en," squares of

bleaching linens and lines of drying ditto were ever before our eyes.

Our arrival was notified to our acquaintance and the public by what my

father's brethren in the law called his advertisement, a large brass

plate on which in letters of suitable size were engraved the words—

MR GRANT, ADVOCATE.

My father established

himself with a clerk and a quantity of law-books in a study, where he

soon had a good deal of work to do. He went every morning to the

Parliament-house, breakfasting before nine to suit William, who was to

be at Dr Hope's chemistry class at that hour, and proceed thence to Dr

Brown's moral philosophy, and then to Mr Playfair's natural philosophy.

A tutor for Greek and Latin awaited him at home, and in the evenings he

had a good three hours' employment making notes and reading up. Six

masters were engaged for us girls, three every day; Mr Penson for the

pianoforte, M. Elouis for the harp, M. L'Espinasse for French, Signor

something for Italian, and Mr I forget who for drawing, Mr Scott for

writing and ciphering, and oh! I was near forgetting a seventh, the most

important of all, Mr Smart for dancing. I was to accompany my father and

mother occasionally to a few select parties, provided I promised

attention to this phalanx of instructors, and never omitted being up in

the morning in time to make breakfast. It was hoped that with Miss

Elphick to look after us, such progress would be made as would make this

a profitable season for everybody. An eye over all was certainly wanted.

My mother breakfasted in bed, and did not leave her room till mid-day.

As I was not welcome in the schoolroom, my studies were carried on in

the drawing-rooms, between the hours of ten, when breakfast was over,

and one, when people began to call. It was just an hour for each master,

and very little spare time at any other period of the day, invitations

flowing in quick, resulting in an eternal round of gaieties that left us

no quiet evening except Sunday.

Our visiting began with

dinners from the heads of the Bar, the Judges, some of the Professors,

and a few others, nearly all Whigs, for the two political parties mixed

very little in those days. The hour was six, the company generally

numbered sixteen, plate, fine wines, middling cookery, bad attendance

and beautiful rooms. One or two young people generally enlivened them.

They were mostly got through before the Christmas vacation. In January

began the routs and balls; they were over by Easter, and then a few more

sociable meetings were thinly spread over the remainder of the spring,

when, having little else to do, I began to profit by the lessons of our

masters. My career of dissipation was therefore but four months thrown

away. It left me, however, a wreck in more ways than one; I was never

strong, and I was quite unequal to all we went through. Mrs Macpherson,

who came up with Belleville in March for a week or two, started when she

saw me, and frightened my mother about me. She had observed no change,

as of course it had come imperceptibly. She had been surprised and

flattered by my success in our small world of fashion. I was on the list

of beauties ; it was intoxicating, but not to me, young and unformed as

I was, and unused to admiration, personal beauty being little spoken of

in the family. I owed my steadiness neither to native good sense nor to

wise council. A happy temper, a genuine love of dancing, a little

Highland pride that took every attention as due to my Grant blood, these

were my safeguards.

The intimate friends of

my father were among the cleverest of the Whigs; Lord Gillies and his

charming wife, John Clerk and his sister, Sir David and Lady

Brewster—more than suspected of Toryism, yet admitted on account of the

Belleville connection and his great reputation—Mr and Mrs Jeffrey, John

Murray, Tommy Thomson, William Clerk. There were others attached to

these brighter stars, who, judiciously mixed among them, improved the

agreeability of the dinner- parties; Lady Molesworth, her handsome

sister Mrs Munro, Mrs Stein, Lady Arbuthnot, Mrs Grant of Kilgraston,

etc. We had had the wisdom to begin the season with a ball ourselves,

before balls were plenty. All the beaux strove for tickets, because all

the belles of the season made their first appearance at it. It was a

decided hit, my mother shining in the style of her preparations, and in

her manner of receiving her company. Every one departed pleased with the

degree of attention paid to each individually.

The return to the Bar had

answered pretty well fees came in usefully. We gave dinners of course,

very pleasant ones, dishes well dressed, wines well chosen, and the

company well selected. My dress and my mother's came from London, from

the little Miss Stewarts, who covered my mother with velvet, satin, and

rich silks, and me with nets, gauzes, Roman pearl trimmings and French

wreaths, with a few substantial morning and dinner dresses. Some of the

fashions were curious. I walked out like a hussar in a dark cloth

pelisse trimmed with fur and braided like the coat of a staff-officer,

boots to match, and a fur cap set on one side, and kept on the head by

means of a cord with long tassels. This equipment was copied by half the

town, it was thought so exquisite.

We wound up our gaieties

by a large evening party, so that all received civilities were fully

repaid to the entire satisfaction of everybody.

This rout, for so these

mere card and conversation parties were called, made more stir than was

intended. It was given in the Easter holidays, or about that time, for

my father was back with us after having been in London. He had gone up

on some appeal cases, and took the opportunity of appearing in his place

in the House of Commons, speaking a little, and voting on several

occasions, particularly on the Corn Law Bill, his opinion on which made

him extremely unpopular with the Radical section of his party, and with

the lower orders throughout the country, who kept clamouring for cheap

bread, while he supported the producer, the agriculturist. His name as a

Protectionist was remarked quickly in Edinburgh where there was hardly

another member of Parliament to be had, and the mob being in its first

excitement the very evening of my mother's rout, she and her

acquaintance came in for a very unpleasant demonstration of its anger

against a former favourite.

Our first intimation of

danger was a volley of stones rattling through the windows, which had

been left with unclosed shutters on account of the heat of the crowded

rooms. A great mob had collected unknown to us, as we had music, and

much noise from the buzz of conversation. By way of improving matters, a

score of ladies fainted. Lady Matilda Wynyard, who had her senses always

about her, came up to my mother and told her not to be frightened; the

General, who had had some hint of the mischief, had given the necessary

orders, and one of the company, a Captain Macpherson, had been already

despatched for the military. A violent ringing of the door bell, and

then the heavy tread of soldiers' feet announced to us that our guard

had come. Then followed voices of command outside, ironical cheers,

groans, hisses, a sad confusion. At last came the tramp of dragoons,

under whose polite attentions the company in some haste departed. Our

guard remained all night and ate up the refreshments provided for our

dismayed guests, with the addition of a cold round of beef which was

fortunately found in the larder.

Next day quiet was

restored, the mob molested us no more, and the incident served as

conversation for a week or more.

The last large party of

the season was given by Grace Baillie in her curious apartments on the

ground floor of an old-fashioned corner house in Queen Street. The rooms

being small and ill-furnished, she hit upon a strange way of arranging

them. All the doors were taken away, all the movables carried off, the

walls were covered with evergreens, through the leaves of which peeped

the light of coloured lamps festooned about with garlands of coarse

paper flowers. Her passages, parlours, bedrooms, cupboards, were all

adorned en suite, and in odd corners were various surprises intended for

the amusement of the visitors; a cage of birds here, a stuffed figure in

a bower there, water trickling over mossy stones into an ivy-covered

basin, a shepherdess, in white muslin a wreath of roses and a crook,

offering ices, a Highland laddie in a kilt presenting lemonade, a cupid

with cake, a gipsy with fruit, intricacies contrived so that no one

might easily find a way through them, while a French horn, or a flute,

or a harp from different directions served rather to delude than to

guide the steps "in wandering mazes lost." It was very ridiculous, and

yet the effect was pretty, and the town so amused by the affair that the

wits did it all into rhyme, and half a dozen poems were written upon

this Arcadian entertainment, describing the scenes and the actors in it

in every variety of style. Sir Alexander Boswell's was the cleverest,

because so neatly sarcastic. My brother's particular friend wrote the

prettiest. In all, we beauties were enumerated with flattering

commendation, but in the friend's the encomium on me was so marked that

it drew the attention of all our acquaintance, and unluckily for me

opened my mother's eyes.

She knew enough of my

father's embarrassments to feel that my "early establishment" was of

importance to the future well-being of the rest of us. She was not sure

of the Bar and the House of Commons answering together. She feared

another winter in Edinburgh might not come, or might not be a gay one, a

second season be less glorious than the first. She had been delighted

with the crowd of admirers, but she had begun to be annoyed at no

serious result following all these attentions. She counted the admirers,

there was no scarcity of them, there were eligibles among them. How had

it come that they had all slipped away?

Poor dear mother 1 while

you were straining your eyes abroad, it never struck you to use them at

home. While you slept so quietly in the mornings you were unaware that

others were awake; while you dreamed of Sheffield gold, and Perthshire

acres, and Ross-shire principalities, the daughter you intended to

dispose of for the benefit of the family had been left to enter upon a

series of sorrows which she never during the whole of her after-life

recovered from the effects of.

It is with pain—the most

extreme pain—that I even now in my old age revert to this unhappy

passage of my youth. I was wrong; my own version of my tale will prove

my errors; but at the same time I was wronged—ay, and more sinned

against than sinning. I would pass the matter over if I could, but

unless I related it you would hardly understand my altered character;

you would see no reason for my doing and not doing much that had been

better either undone or done differently. You would wonder without

comprehending, accuse without excusing; in short, you would know me not.

Therefore, with as much fairness as can be expected from feelings deeply

wounded and ill understood, I will recall the short romance which

changed all things in life to me.

The first year William

was at college he made the acquaintance of a young man a few years older

than himself, son of one of the professors. His friend was tall, dark,

handsome, engaging in his manners, agreeable in conversation, and

considered to possess abilities worthy of the talented race to which he

belonged. The Bar was to be his profession, more by way of occupation

for him in the meanwhile than for any need he would have to practise law

for a livelihood. He was an only son, his father was rich, his mother

had been an heiress, and he was the heir of an old, nearly bedrid

bachelor uncle who possessed a landed property on the banks of the

Tweed.

Was it fair, when a

marriage was impossible, to let two young people pass day after day for

months together? My brother, introduced by his friend to the professor's

family during the first year he was at college, soon became intimate in

the house. The father was very attentive to him, the mother particularly

liked him, the three sisters, none of them quite young, treated him as a

relation. William wrote constantly of them, and talked so much about

them when at the Doune for the summer vacation that we rallied him

perpetually on his excessive partiality, my mother frequently joining in

our good-humoured quizzing. It never struck us that on these occasions

my father never entered into our pleasantry.

When we all removed to

Edinburgh William lost no time in introducing his friend to us; all took

to him; he was my constant partner, joined us in our walks, sat with us

in the morning, was invited frequently, and sometimes asked to stay for

the family dinner. It never entered my head that his serious attentions

would be disagreeable, nor did it enter my mother's, I believe, that

such would ever grow out of our brother-and-sister intimacy. I made

acquaintance with the sisters and exchanged calls as young ladies did

then in Edinburgh; and then I first thought it odd that the seniors of

each family, so particularly obliging as they were to the junior members

of each other's households, made no move towards an acquaintance on

their own parts. The gentlemen, much occupied with their affairs, were

excusable, but the ladies—what could prevent the common forms of

civility between them? I had by this time become shy of making any

remarks on them, but Jane, who had marvelled too, asked my mother the

question. My mother's answer was quite satisfactory. She was the latest

corner, it was not her place to call first on old residents. I had no

way of arriving at the reasons on the other side, but the fact of the

non- intercourse annoyed me, and caused me frequently a few moments more

of thought than I was in the habit of indulging in. Then came Miss

Baillie's fête, and the poem in which I figured so gracefully. It was in

every mouth, for in itself it was a gem. None but a lover could have

mingled so much tenderness with his admiration.

On the poet's next visit

my mother received him coldly. At our next meeting she declined his

attendance. At the next party she forbade my dancing with him: "after

the indelicate manner in which he had brought my name before the public

in connection with his own, it was necessary to meet such forwardness

with a reserve that would keep his presumption at a proper distance." I

listened in silence, utterly dismayed, and might have submitted

sorrowfully and patiently, but she went too far. She added that she was

not asking much of me, for "this disagreeable young man had no attaching

qualities; he was not good-looking, nor well-bred, nor clever, nor much

considered by persons of judgment, and certainly by birth no way the

equal of a Grant of Rothiemurchus!"

I left the room, flew to

my own little attic (what a comfort that corner all to myself was

then!), I laid my head upon my bed, vainly trying to keep back the

tears. The words darted through my brain, "all false, quite false—what

can it be? what will become of us?" Long I stayed there till a new turn

took me, the turn of unmitigated anger. Were we puppets, to be moved

about by strings? Were we supposed to have neither sense nor feeling?

Was I so poor in heart as to be able to like to-day, to loathe

to-morrow? so deficient as to be incapable of seeing with my own eyes?

This long familiar intimacy permitted, then suddenly broken upon false

pretences! "They don't know me," thought I; alas! I did not know myself.

To my mother throughout that memorable day I never articulated one

syllable. My father was in London.

My first determination

was to see my poet and inquire of him whether he were aware of any

private enmity between our houses. Fortunately he also had decided on

seeking an interview with me in order to find out what it was that my

mother had so suddenly taken amiss in him. Both so resolved, we made the

meeting out, and a pretty Romeo and Juliet business it ended in.

There was an ancient

feud, a college quarrel between our fathers which neither had ever made

a movement to forgive. It was more guessed at from some words his mother

had dropped than clearly ascertained, but so much he had too late

discovered, that a more intimate connection would be as distasteful to

the one side as to the other.

We were young, we were

very much in love, we were hopeful; life looked so fair, it had been

latterly so happy, we could conceive of no old resentments between

parents that would not yield to the welfare of their children. He

remembered that his father's own marriage had been an elopement followed

by forgiveness and a long lifetime of conjugal felicity. I recollected

my mother telling me of the Montague and Capulet feud between the

Neshams and the Ironides, how my grandfather had sped so ill for years

in his wooing, and how my grandmother's constancy had carried the day,

and how all parties had "as usual" been reconciled. Also when my father

had been reading some of the old comedies to us, and hit upon the

Clandestine Marriage, though he effected to reprobate the conduct of

Miss Fanny, his whole sympathy was with her and her friend Lord Ogleby,

so that he leaned very lightly on her error. He would laugh so merrily

too at the old ballads, "Whistle and I'll come to ye, my lad," "Low doun

i' the broom," etc. These lessons had made quite as much impression as

more moral ones. So, reassured by these arguments, we agreed to wait, to

keep up our spirits, to be true to each other, and to trust to the

chapter of accidents.

In all this there was

nothing wrong, but a secret correspondence in which we indulged was

certainly not right. We knew we should meet but seldom, never without

witnesses, and I had not the resolution to refuse the only method left

us of softening our separation. One of these stray notes from him to me

was intercepted by my mother, and some of the expressions employed were

so startling to her that in a country like Scotland, where so little

constitutes a marriage, she almost feared we had bound ourselves

sufficiently to cause considerable annoyance, to say the least of it.

She therefore consulted Lord Gillies as her confidential adviser, and he

had a conference with Lord Glenlee, the trusted lawyer on the other

side, and then the young people were spoken to, to very little purpose.

What passed in the other

house I could only guess at from after-circumstances. In ours, Lord

Gillies was left by my mother in the room with me; he was always gruff,

cold, short in manner, and no favourite with me, he was therefore ill

selected for the task of inducing a young lady to give up her lover. I

heard him respectfully, of course, the more so as he avoided all blame

of either of us, neither did he attempt to approve of the conduct of our

elders; he restricted his arguments to the inexperience of youth, the

insurmountable aversion of the two fathers, the cruelty of severing

family ties, dividing those who had hitherto lived lovingly together,

the indecorum of a woman entering a family which not only would not

welcome her, but the head of which repudiated her. He counselled me, by

every consideration of propriety, affection, and duty, to give "this

foolish matter up."

"Ah, Lord Gillies,"

thought I, "did you give up Elizabeth Carnegie? did she give you up?

When you dared not meet openly, what friend abetted you secretly?" I

wish I had had the courage to say this, but I was so abashed, so

nervous, that words would not come. I was silent.

To my mother I found

courage to say that I had heard no reasons which would move me to break

the word solemnly given, the troth plighted, and could only repeat that

we were resigned to wait.

Lord Glenlee made as

little progress ; he had had more ofa storm to encounter, indignation

having produced eloquence. Affairs therefore remained at a standstill.

The fathers kept aloof—mine indeed was still in London; but the mothers

agreed to meet and see what could be managed through their agency.

Nothing satisfactory. I would promise nothing, sign nothing, change

nothing, without an interview with my betrothed to hear from his own

lips his wishes. As if my mind had flown to meet his, he made exactly

the same reply to similar importunities. No interview would be granted,

so there we stopped again.

At length his mother

proposed to come and see me, and to bring with her a letter from him,

which I was to burn in her presence after reading, and might answer, and

she would carry the answer back on the same terms. I knew her well, for

she had been always kind to me and had encouraged my intimacy with her

daughters; she had known nothing of my greater intimacy with her son.

The letter was very lover-like, very tender to me, very indignant with

every one else, very undutiful and very devoted, less patient than we

had agreed on being, more audacious than I dared to be. I read it in

much agitation—read it, and then laid it on the fire. "And now before

you answer it, my poor dear child," said this sensible and excellent

woman, "listen to the very few words I must say to you," and then in the

gentlest manner, but rationally and truthfully, she laid before me all

the circumstances of our unhappy case, and bade me judge for myself on

what was fitting for me to do. She indeed altered all my high resolves,

annihilated all my hopes, yet she soothed while she probed, and she

called forth feelings of duty, of self-respect, of proper self-

sacrifice, in place of the mere passion that had hitherto governed me.

She told me she would have taken me to her heart as a daughter, for the

good disposition that shone through some imperfections, and for the true

love I bore her son, but her husband would never do so, nor endure an

alliance with my father's child. They had been friends, intimate

friends, in their college days; they had quarrelled, on what grounds

neither had been known to give to any human being the most distant hint;

but in proportion to their former affection was the inveteracy of their

after-dislike. All communication was over between them, they met as

strangers, and were never known to allude to each other. My father had

written to my mother that he would rather see me in the grave than the

wife of that man's son. Her husband had said to her that if that

marriage took place he would never speak to his son again, never notice

him, nor allow of his being noticed by the family. She told me her

husband had a vindictive as well as a violent temper, and that she

suspected there must be a touch of the same disposition in my father, or

so determined an enmity could not have existed. They felt that they were

wrong, as was evidenced by the extra attention each had paid the other's

children. At their age she feared there was no cure. She came to tell me

the whole truth, to show me that, with such feelings active against us,

nothing but serious unhappiness lay before us, in which distress all

connections must expect to share. She said we had been cruelly used,

most undesignedly; she blamed neither so far, but she had satisfied her

judgment that the peculiar situation of the families now demanded from

me this sacrifice; I must set free her son, he could not give me up

honourably. She added that great trials produced great characters, that

fine natures rose above difficulties, that few women, or men either,

wedded their first love, that these disappointments were salutary. She

said what she liked, for I seldom answered her; my doom was sealed; I

was not going to bring misery in my train to any family, to divide it

and humiliate myself, destroy perhaps the future of the man I loved. The

picture of the old gentleman too was far from pleasing, and may have

affected, though unconsciously, the timid nature that was now so

crushed. I told her I would write what she dictated, sign Lord Glenlee's

"renunciation," promise to hold no secret communication with her son. I

kept my word; she took back a short note in which, for the reasons his

mother would explain to him, I gave him back his troth. He wrote, and I

never opened his letter; he came and I would not speak, but as a cold

acquaintance. What pain it was to me those who have gone through the

same ordeal alone could comprehend. His angry disappointment was the

worst to bear; I felt it was unjust, and yet it could not be explained

away, or pacified. I caught a cold luckily, and kept my room awhile. I

think I should have died if I had not been left to rest a bit.

My father on his return

from London never once alluded to this heart-breaking subject; I think

he felt for me, for he was more considerate than usual. He bought a nice

pony and took me rides, sent me twice a week to Seafield for warm baths,

and used to beg me off the parties, saying I had been racketed to death,

when my mother would get angry and say such affectation was

unendurable—girls in her day did as they were bid without fancying

themselves heroines. She was very hard upon me, and I am sure I did not

provoke her; I was utterly stricken down. What weary days dragged on

till the month of July brought the change to the Highlands.

Had I been left in quiet

to time, my own sense of duty, my conviction of having acted rightly, a

natural spring of cheerfulness, with occupation, change, etc., would

have acted together to restore lost peace of mind, and the lesson,

severe as it was, would have certainly worked for good, had it done no

more than to have sobered a too sanguine disposition. Had my father's

judicious silence been observed by all, how much happier would it have

been for every one! Miss Elphick returned to us in June, and I fancy

received from my mother her version of my delinquencies, for what I had

to endure in the shape of rubs, snubs, and sneers and impertinences, no

impulsive temper such as mine could possibly have put up with. My poor

mother dealt too much in the hard-hit line herself, and she worried me

with another odious lover. Defenceless from being blamable, for I should

have entered into no engagement unsanctioned, I had only to bear in

silence this never- ending series of irritations. Between them, I think

they crazed me; my own faults slid into the shade comfortably shrouded

behind the cruelties of which I was the victim, and all my corruption

rising, I actually in sober earnest formed a deliberate plan to punish

my principal oppressor—not Miss Elphick, she could get a slap or two

very well by the way. My resolve was to wound my mother where she was

most vulnerable, to tantalise her with the hope of what she most wished

for, and then to disappoint her. I am ashamed now to think of the state

of mind I was in; I was astray indeed, with none to guide me, and I

suffered for it; but I caused suffering, and that satisfied me. It was

many a year yet before my rebellious spirit learned to kiss the rod.

In journeying to the

Highlands we were to stop at Perth. We reached this pretty town early,

and were surprised by a visit from Mr Anderson Blair, a young gentleman

possessing property in the Carse of Gowrie, with whom our family had got

very intimate during the winter. William was not with us, he had gone on

a tour through the West Highlands with a very nice person, a college

friend, an Englishman. He came to Edinburgh as Mr Shore, rather later

than was customary, for he was by no means so young as William and

others attending the classes, but being rich, having no profession, and

not college-bred, he thought a term or two under our professors—our

University was then deservedly celebrated—would be a profitable way of

passing idle time. Just before he and my brother set out in their tandem

with their servants, a second large fortune was left to this favoured

son of a mercantile race, for which, however, he had to take the

ridiculous name of Nightingale.

Mr Blair owed this

well-sounding addition to the more humble Anderson, borne by all the

other branches of his large and prosperous family, to the bequest of an

old relation. Her legacy was very inferior in amount to the one left to

Mr Nightingale, but the pretty estate of Inchyra with a good modern

house overlooking the Tay, was part of it, and old Mr John Anderson, the

father, was supposed to have died rich. He was therefore a charming

escort for my mother about the town; we had none of us ever seen so much

of Perth before. We were taken to sights of all kinds, to shops among

the rest, and Perth being famous for whips and gloves, while we admired

Mr Blair bought, and Jane and I were desired to accept each a very

pretty riding-whip, and a packet of gloves was divided between us. Of

course our gallant acquaintance was invited to dinner.

The walk had been so

agreeable, the weather was so extremely beautiful, it was proposed, I

can hardly tell by whom, to drive no farther than to Dunkeld next

morning, and spend the remainder of the day in wandering through all the

beautiful grounds along the miles and miles of walks conducted by the

river-side through the wood and up the mountains. "Have you any

objection to such an arrangement, Eli?" said my father to me. "I, papa!

none in the world." It just suited my tactics; accordingly so it was

settled, and a very enjoyable day we spent. The scenery is exquisite,

every step leads to new beauties, and after the wanderings of the

morning it was but a change of pleasure to return to the quiet inn at

Inver to dine and rest, and have Neil Gow in the evening to play the

violin. It was the last time we were there; the next time we travelled

the road the new bridge over the Tay at Dunkeld was finished, the new

inn, the Duke's Arms, opened, the ferry and the inn at Inver done up,

and Neil Gow dead.

Apropos of the Duke's

Arms, ages after, when our dear amusing uncle Ralph was visiting us in

the Highlands, he made a large party laugh, as indeed he did frcqucntly,

by his comical way of turning dry facts into fun. A coach was started by

some enterprising individual to run between Dunkeld and Blair during the

summer season, which announcement my uncle read as if from the

advertisement in the newspaper as follows: "Pleasing intelligence. The

Duchess of Athole starts every morning from the Duke's Arms at eight

o'clock. . . ." There was no need to manufacture any more of the

sentence.

Our obliging friend left

us with the consolatory information that we should meet again before the

12th of August, as a letter from Mr Nightingale had brought his

agreement to a plan for them to spend the autumn in the Highlands. They

had taken the Invereshie shootings, and were to lodge at the Dell of

Killiehuntly with John and Betty Campbell.

Our first three weeks at

home were very quiet, no company arriving, and my father being absent at

Inverness, Forres, Garmouth, etc., on business. We had all our humble

friends to see, all our favourite spots to visit. To me the repose was

delightful, and had I been spared all those unkind jibes, my irritated

feelings might have calmed down and softened my temper; exasperated as

they continually were by the most cutting allusions, the persuasion that

I had been most unjustly treated and was now suffering unjustly for the

faults of others, grew day by day stronger and stronger, and estranged

me completely from those of the family who so perpetually annoyed me.

Enough of this; so it was, blame me who will.

After this quiet

beginning our Highland autumn set in gaily. The 10th of August filled

every house in the country in preparation for the 12th. Kinrara was

full, though Lord Huntly had not come with the Marchioness; some family

business detained him in the south, or he made pretence of it, in order

that his very shy wife might have no assistance in doing the honours,

and so rub off some of the awkward reserve which so much annoyed him.

Belleville was full, the inns were full, the farm-houses attached to the

shootings let were full, the whole country was alive, and Mr

Nightingale, Mr Blair, and my brother arrived at the Doune. Other guests

succeeded them, and what with rides and walks in the mornings, dinners

and dances in the evenings, expeditions to distant lochs or glens or

other picturesque localities, the Pitmain Tryst and the Inverness

Meeting, a merrier shooting season was never passed. So every one said.

I do not remember any one person as very prominent among the crowd, nor

anything very interesting by way of conversation. The Battle of Waterloo

and its heroes did duty for all else, our Highlanders having had their

full share of its glories.

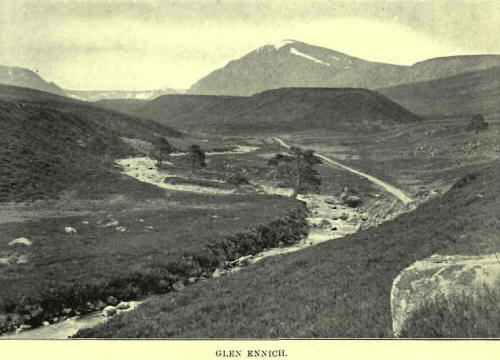

We ladies went up for the

first time this year to Glen Ennich, our shooting friends with us. The

way lay through the birch wood to Tullochgrue, past Macalpine's well and

a corner of the fir forest and a wide heath, till we reached the banks

of the Luinach, up the rapid course of which we went till the heath

narrowed to a glen, rocks and hills closed in upon us, and we came upon

a sheet of water terminating the cul de sac, fed by a cataract tumbling

down for ever over the face of the precipice at the end of it. All the

party rode on ponies caught about the country, each rider attended by a

man at the bridle-head.

A very pleasant day we

passed, many merry adventures of course taking place in so singular a

cavalcade. We halted at a fine spring to pass round a refreshing drink

of whisky and water, but did not unload our sumpterhorses till we

reached the granite-pebbled shore of the Loch. Fairy tales belong to

this beautiful wilderness; the steep rock on the one hand is the

dwelling of the Bodach of the Scarigour, and the castle- like row of

precipitous banks on the other is the domain of the Bodach of the

Corriegowanthill—titles of honour these in fairyland, whose high

condition did not however prevent their owners from quarrelling, for no

mortal ever gained the good graces of the one without offending the

other, loud laughing mockery ever filling the glen from one potentate or

the other, whenever their territories were invaded after certain hours.

Good Mr Stalker the dominic had been prevented from continuing his

fishing there by the extreme rudeness of the Corriegowanthill, although

encouraged by his opposite neighbour and fortified by several glasses of

stiff grog. We met with no opposition from either; probably the Laird

and all belonging to him were unassailable. We had a stroll and our

luncheon, and we filled our baskets with those delicious delicate char

which abound in Loch Ennich, and returned gaily home in safety.

The Inverness Meeting was

a bad one, I recollect, no new beauties, a failure of old friends, and a

dearth of the family connections. My last year's friend, the new member

for Ross-shire, Mr Mackenzie of Applecross, was at this Meeting, more

agreeable than ever, but looking extremely ill. I introduced him by

desire to my cousin Charlotte Rose, who got on with him capitally. He

was a plain man, and he had a buck tooth to which some one had called

attention, and it was soon the only topic spoken of, for an old prophecy

ran that whenever a mad Lovat, a childless--, and an Applecross with a

buck tooth met, there would be an end of Seaforth. The buck tooth all

could see, the mad Lovat was equally conspicuous, and though Mrs-- had

two handsome sons born after several years of childless wedlock, nobody

ever thought of fathering them on her husband. In the beginning of this

year Seaforth, the Chief of the Mackenzies, boasted of two promising

sons; both were gone, died within a few months of each other. The

Chieftainship went to another branch, but the lands and the old Castle

of Brahan would descend after Lord Seaforth's death to his daughter,

Lady Hood—an end of Caber-Feigh. This made every one melancholy, and the

deaths of course kept many away from the Meeting. |