|

Ferns and Tree Ferns

The earliest traces of

vegetable life yet discovered in the most ancient fossiliferous rocks,

consist of fragments of sea-weed, accompanying graptolites, or sea-pens,

in the anthracite beds of the Silurian system, which in all probability

owed their origin to the decomposition of plants of this description, once

forming submarine meadows, where zoophytes nestled and trilobites swam. So

far as geological investigation has yet gone, it does not appear that a

terrestrial flora flourished on the shores of the primeval sea till the

age of the old red sandstone, when fishes of singular conformation,such as

the pterichthys, with its wing-like arms, disported in the waters. The

first indications of land plants are found in the lower beds of that

series of rocks, and consist of the remains of lycopodiums or club -

mosses, of tree-ferns, and the wood of coniferous trees, resembling the

modern araucaria, or Norfolk Island pine. The deposits of this era, both

in Ireland and Scotland, have yielded fragments of the fronds or leaves of

a tree-fern named Cyclopteris Hibernica, which disappeared before the dawn

of the carboniferous period, when, as we have seen, ferns and their allies

prevailed over a great portion of the surface of the earth, laying up, for

the use of distant ages, beds of coal, deriving their carbon from the

carbonic acid gas floating in the then existing atmosphere, and their

hydrogen from the decomposition of water, which, descending in rain,

mottled, with its drops, the yielding sand; while, upon the same shores,

the ripple of the rising and receding tide was tracing the curving and

anastomosing lines now so frequently observable on slabs of building and

paving stones. We thus learn, from the traces of life-history in the

ancient rocks, that, however varied the forms of animals and plants

existing in successive geological epochs, the conditions of life have been

uniform in all ages. Geology teaches us, to use the words of Professor

Owen, that "the globe allotted to man has revolved in its orbit through a

period of time so vast, that the mind, in the endeavour to realise it, is

strained by an effort like that by which it strives to conceive the space

dividing the solar system from the most distant nebulae." The pages of the

rocky science bear evidence not less equivocal to the conditions in which

organised beings existed upon the earth's surface during all the different

eras which it is the province of the geologist to investigate and define.

The light and heat of the sun reached the earth through an atmosphere not

different from that by which the surface of the globe at present receives

the same vivifying influences. The eye of the trilobite was constructed

upon the same optical principles, and adapted to the same conditions of

light and vision, as the eye of the existing crustacean and insect.

Vaporised moisture ascended from earth and sea, and became condensed in

the atmosphere, whence it was precipitated in fertilising showers of rain.

These showers have not only left, in the strata of successive systems, the

casts of rain-marks, indicating by their slope or shape the direction from

which they were blown by the wind; but the little rills formed by the

gathering drops, as they rolled along the surface of the sand or mud, have

also had their traces preserved—a phenomenon which has been detected in

Lower Canada in rocks so early as those of the old red sandstone,

contemporaneous with the first vestiges of terrestrial vegetation, and

recording the most ancient showers of rain of which we have any geological

memorial. The study of fossil botany shews, in like manner, that the

extinct vegetables of the palćozoic flora must have existed in conditions

of the air and earth, such as are still essential to the growth and

development of the plant. But while we thus derive from the rocks

incontestable proofs of the uniformity of the laws of nature throughout

prolonged and successive epochs, we are called to contemplate an

astonishing variety in the productions existing at different times in the

organised world. Entire races of animals and plants were again and again

extinguished, and replaced by new tribes, which have no specific

representatives in our present flora and fauna. Yet amidst boundless

diversity of form and function in the animal and vegetable kingdoms,

viewed along the entire course of creation, we are able to discover an

undeviating adherence to typical unity in the glorious plan of the

Almighty's handiwork. In evolving this great central principle of the

organic creation, science occupies its true position as the handmaid of

religion. From the realms of living nature, and the records of past

creations, it brings, as a tribute to the altar of the Christian faith, a

confirmation of the personal unity of the adorable " I AM," revealed in

the pages of eternal truth ; and in demonstrating the unity of the

Creator, by tracing through creation the archetypical idea which must have

dwelt for ever in the Divine Mind, it has also enriched natural theology

with fresh and vivid illustrations of the wisdom and goodness of God, in

adapting the typical forms of animals and plants to an endless diversity

of benevolent purposes. The science of geology is a history of successive

miracles of creation. The subtle sceptic who demanded the testimony of

experience to convince him of the possibility of a miracle, lived before

geology had borne evidence on the subject such as no rational man will be

hardy enough to gainsay. It was a shrewd remark of Hugh Miller's —"Hume is

at length answered by the severe truths of the stony science. He was not,

according to Job, in league with the stones of the field,' and they have

risen in irresistible warfare against him in the Creator's behalf."

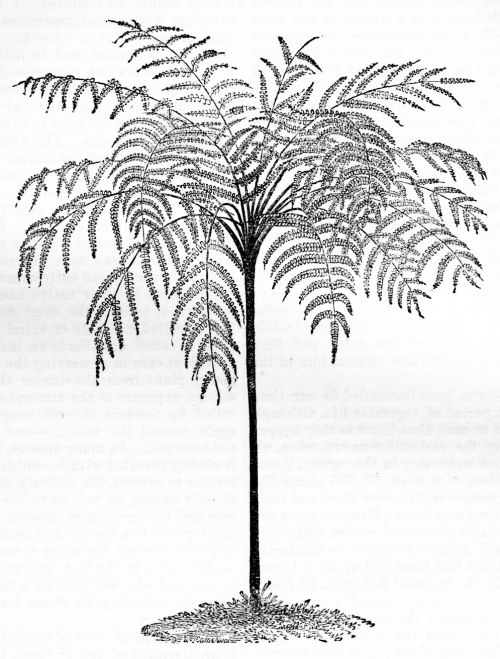

Ferns, and tree-ferns, have

descended to our time from the remotest period of vegetable life, although

they nowhere exist in such abundance as they appear to have done during

the carboniferous era, when, although the vegetation was scanty in the

variety, it was profuse in the number, of species. Of 500 plants

discovered in the coal measures, 346 were ferns and their allies, nearly

300 being true ferns. Many of these are preserved in the shales of the

coal mines, with their fossilised fronds and minute venation as distinctly

defined as if the plants had been laid up in a botanist's herbarium. In

the mines of Bohemia, Dr Buck-land found the ferns and other vegetable

remains of the coal exceeding in beauty the most elaborate imitations of

living" foliage upon the painted ceilings of Italian palaces. The roofs of

the mines were covered as with a canopy of gorgeous tapestry, enriched

with festoons of most graceful foliage, flung in wild, irregular profusion

over every portion of the surface, the effect being heightened by the

contrast between the shining black colour of the coal plants and the light

hues of the rocks to which they were attached. The ferns of the English

coal-fields number about 140. The existing British species of ferns,

including varieties raised to the rank of species, are under 50. In

tropical countries, especially those having an insular climate, such as St

Helena and the Society Islands, ferns preponderate over flowering plants.

The extra-tropical island of New Zealand is preeminently the region of

ferns, many of them arborescent, and of their allies the club-mosses,

which give a luxuriant aspect to the vegetation, where flowering plants

are comparatively rare. Within an area of a few acres, Dr Joseph Hooker

observed thirty-six kinds of ferns, while the same space produced scarcely

twelve flowering plants and trees. Hence, New Zealand is supposed to

possess a climate somewhat resembling that of the carboniferous period,

which is believed to have been humid, mild, and equable.

The lowly ferns of this

country, whose graceful fronds adorn our hillsides and valleys, and fringe

the shady banks of burn and rivulet with their luxuriant verdure, are

characterised by having a creeping stem, or rhizome, running along or

under the surface of the ground. The stem of the tree-fern of other lands

rises into the air, in the form of a slender but stately trunk, surmounted

by a crown of elegant drooping fronds, and resembles a palm in its

appearance and habit of growth. When fully formed, the trunk is hollow,

and is marked on the outside with the scars or cicatrices left by the

falling fronds, which, along with the peculiar appearance of the cellular

tissue and vascular bundles of the interior, enable the botanist to

identify their fossilised remains in the rocks. The stem is formed by the

union of the bases of the leaves, which carry up with them the growing

point; and as the fern-stem, whether horizontal or vertical, increases

only by additions to the summit, this family of plants is called acrogens,

or summit-growers. In the young state, the fronds are rolled up in a

crosier-like manner, familiar to all who have observed the development of

ferns in spring and early summer; and the fronds of tree-ferns, in their

native haunts and in our conservatories, exhibit the same curious

arrangement. The so-called circinate or spiral mode in which the frond is

coiled up, affords an instructive example of provident care in preserving

the tender parts of the young plant from the danger they would incur by

sudden exposure to the atmosphere. Each leaflet is rolled up towards the

rib supporting it,—the rib again toward the midrib,—and the midrib toward

the footstalk. In many species, the crosier-like coil is closely invested

with brownish scales, serving still further to protect the delicate frond

from the chills of early spring, as well as to bar the access of moisture

and the invasion of insects. The whole arrangement presents a beautiful

instance of the "packing" of plants, during the stage of venation, or when

the tender leaf is in the bud; and may readily be studied by any one who

will pick up a fern frond, while it is leisurely unfolding its green

leaflets to the genial airs of spring.

In the tropical zone of

vegetation, tree-ferns grow at an elevation of two or three thousand feet

above the level of the sea, and in favourable circumstances their trunks

attain a height of forty or fifty feet. They can only be imported into

this country in their young state, and then not without difficulty; but

even in their most developed form, they exhibit, on a diminished scale, in

the conservatory, the majesty and grace of their structure and habits in

the warm and humid climate of tropical regions, and even the more

temperate parts of the southern hemisphere, where they give a marked

character to the physiognomy of vegetation. Humboldt describes the

arborescent ferns growing in the shaded clefts on the slopes of the

Cordilleras, as standing out in bold relief against the azure of the sky,

with their thick cylindrical trunks, and delicate lace-like foliage, and

where they are associated with the cinchona tree, yielding the Peruvian

bark. The Cyathea arborea, known in our collections, is a native of the

West Indies, where it grows to a height of twenty-five feet. St Helena

produces the Dicksonia arborescens, which has been observed nowhere else

in the world. One of the most magnificent is Alsophylla excelsa, a native

of Norfolk Island, where it attains to a height of fifty to eighty feet,

with a trunk scarcely a foot in diameter, and a coronet of long pensile

fronds. Speaking of tree-ferns in Australia, twenty feet high, Captain

Mundy remarks:—"When I left England, some of my friends were fern-mad, and

were nursing microscopic varieties with vast anxiety. Would that I could

place them for a minute beneath the patulous umbrella of this magnificent

species of cryptogamia." One familiar arborescent species (Aspidium

baromez), the barometz, or baranetz, called also the Scythian lamb,

possesses a woolly rhizome; and when the fronds are cut off, leaving a

small portion of the stalk, and the specimen is turned upside down,

credulous people have been persuaded, by its appearance, that in the

deserts of Scythia there existed creatures half-animal, half-plant. Sir

Hans Sloane, who founded the British Museum, described and figured it, in

the Philosophical Transactions, under the name of the Tartarian Lamb.

Darwin introduces this fantastic fiction into the "Loves of the Plants:"—

"Cradled in snow, and fann'd

by arctic air,

Shines, gentle Barometz! thy golden hair;

Rooted in earth, each cloven hoof descends,

And round and round her flexile neck she bends;

Crops the gray coral moss and hoary thyme,

Or laps with rosy tongue the melting rime;

Eyes with mute tenderness her distant dam,

Or seems to bleat, a Vegetable Lamb." |