A Christian thinker and worker of the last century

set himself one day to consider the probable order in which the gospel

of Christ would spread throughout the world, and he put on record the

result of his thoughts. He looked at the promise, "The earth shall be

full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea," and

then at the actual condition of Christian and heathen countries; and,

after weighing probabilities, he judged that there would be first a

fuller setting up of the kingdom of God in the hearts of English and

American Christians, whence it would spread from house to house, from

town to town, and from one kingdom to another. Thus, he contemplated the

triumph of the gospel throughout Europe, till all Papists should forsake

their superstitions; and thence to Asia, till Mohammedans should own the

truth; and thence to such heathens as, living near Christian nations,

are in habits of intercourse with them—to the various tribes of Tartars,

to the dwellers in the East Indies and in Africa, till at last the

gospel should find its way into the very heart of China and Japan. Yet,

after this survey, one grand difficulty remained. By what arrangements

of Providence were the dwellers in the South Seas to be Christianised ?

How should these outcasts, peopling insignificant ocean-girt rocks, or

low-lying and scattered coral islets, be taught the way to the Saviour?

Here reason was baffled; but faith, remembering how Ezekiel was "taken

by the Spirit," and Philip led on his desert route by an angel,

confidently affirmed that, in God's own way, this least likely work

should yet be accomplished.

Eighty years have passed since then, and how

different has been the course of events. Japan as firmly closed against

Scripture-teaching as ever; Romanism and Mohammedanism still shutting

out the light; the interior of Africa barely touched by the hand of

Christian enterprise; while, to almost every group and island of the

vast and thickly-studded Pacific Ocean, the Word of God has come in

power, and from their Christian assemblies the incense of many prayers

is day by day ascending to heaven. Surely, if John Wesley could now look

at the work in the Harvey Islands and in Tahiti; in Samoa, in Tonga, and

Fiji, he would rejoice like those who at Jerusalem heard Peter's

story—"held their peace and glorified God, saying, Then hath God also to

the Gentiles granted repentance unto life;" only with this difference—

their doubt had relation to God's willingness to save; his, to the mode

and order in which the Divine wisdom would choose to act.

The South Sea missions generally have attracted the

attention of English Christians of all Churches, and many a pleasant

book has told the interesting story of the first missionaries in the

Duff, and of their successors. But the Fiji group is less known than

most, and on many grounds it has a claim on our Good Words. The

fact that the present lord of Fiji, Thakombau, offers its sovereignty to

our queen, leads statesmen and cotton-manufacturers to inquiry. Within

the last few weeks a man of science has left England to study its flora;

and no true Christian can fail to regard with deep interest the scene of

one of the most wonderful triumphs of modern Christian missions. While

angels, with their piercing intellects, desire to look into the blessed

truths of Christian doctrine, surely we, wayfarers and simple ones,

plain and practical, placed where we can, for a little while, so well

investigate the effects of that doctrine, should never grow weary in

gathering new facts illustrative of its power unto salvation.

The Fiji islands are a group numbering two hundred

and eleven, spreading over about 40,000 square miles of the Pacific

Ocean, and situated about 1000 miles from New Zealand. Many of them are

surrounded by "the white reef, that," according to one of the latest and

happiest descriptions, "in Pacific islands encircles their inner

lakelets, and shuts them from the surf and sound of sea. Clear and calm

they rest, reflecting fringed shadows of the palm-trees, and the passing

of fretted clouds across their own sweet circle of blue sky; while

beyond, and round and round their coral bar, lies the blue of sea and

heaven together—blue of eternal deep." Some of the islands are very

small and flat; others raise their peaked summits to the height of four

or five thousand feet, and the two largest are from three to four

hundred miles in circumference. They are beautiful of aspect, and rich

in productive soil. They are covered with a luxuriant growth of tropical

plants and trees, from lowest coral reef to highest peak, save where the

hand of native cultivation has cleared away large tracts of wood by

fire, in order to prepare planting-ground for yams, bananas, and taro.

Where this has been done one must rise to the level of a thousand feet

before reaching masses of forest growth.

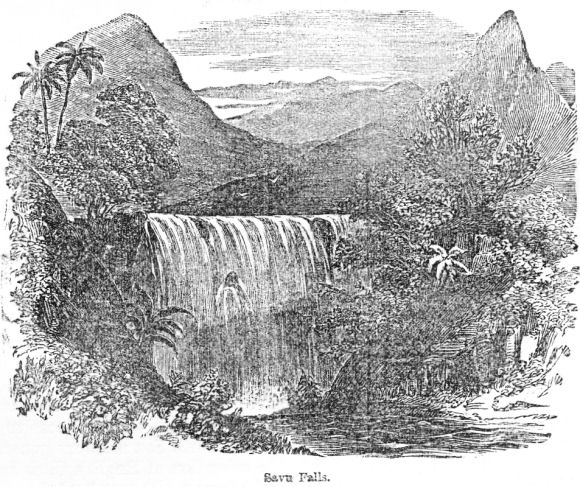

After passing these, and nearing the summit of the

hills, trees are found to be sparsely scattered; but ferns of many

kinds, with orchids and mosses, abound. Lower down, and following the

course of the pleasant and fertilising rivulets, is an interlacing

undergrowth of bushes and climbing plants. The mangrove seeks low and

swampy places near the sea, pushes its way along muddy creeks, creeps

over tracts of coral reef, and flourishes even where its young offshoots

are covered three or four feet, at high tide, with salt water. Nature is

here prodigal of her varied tints and forms; indeed, so favourable to

vegetable life are the climate and soil of these islands, that turnip,

radish, and mustard-seed, planted by Mr Brackenridge, (an American

horticulturist who accompanied the United States exploring expedition,)

shewed their cotyledon leaves in twenty-four hours; melons, cucumbers,

and pumpkins sprang up in three days; beans and peas in four. In four

weeks from the time of planting, radishes and lettuces were fit for use,

and in five weeks marrow-fat peas. There is a difference here, as in all

the large Polynesian islands, between the two sides of the islands. On

the weather side showers are frequent, and vegetation knows no check; to

leeward droughts are common, and the sultry sun sets his scorching mark

upon the land. Though this is true, and though there are rocky places

hopelessly barren, yet it is said that two-thirds of the entire surface

of the islands is available for cultivation.

A small traffic with European ships was begun in the

year 1806, sandalwood being then the chief article of barter. That

supply has ceased; but the Fijians now trade with America, England, and

Hamburgh, the principal exports being cocoa-nut oil, tortoise-shell, and

beche-de-mer. Of all tropical trees the cocoa-nut seems to meet the

largest number of demands from those who live among its groves; and to

exaggerate its value is scarcely possible. Food, and light, and

clothing; drinking-cups, cordage, fishing-tackle, carpeting; wood for

building, and oil for lubrication are all supplied by this ever-ready

friend. Home consumption being great, cocoa-nut oil is not likely to be

very largely exported; yet in 1.859 seven hundred tons were sent to

America.

The search for tortoise-shell gives occupation to

many of the natives, and some of the small uninhabited islands are

visited, at certain seasons, for this express purpose. From December to

March, fishermen remain in the haunts of the turtle, and intercept the

slow travellers as they return from feeding or from laying their eggs.

The female turtle is most prized. Sometimes they are caught in nets of

strong cocoa-nut sinnet, with meshes of seven or eight inches square;

but, after they become entangled, the difficulty of actual capture

remains. The Fijians will dive and seize the turtle, overcoming him in

his own element, not without a severe struggle. Should the resistance

offered be unusually vigorous, his captor tries to insert his finger and

thumb in the creature's eye-socket, and this done, the turtle owns

himself vanquished by rising to the surface. He is then dragged to the

boat and laid on his back. Pour or five men will sometimes be engaged in

securing one such prize. Live turtle are kept in pens, by the chiefs,

ready for sale. The thirteen plates that cover the back and sides of the

turtle (the tortoise-shell of commerce) are called "a head," and weigh

from one to seven pounds.

Those who have lived in Fiji tell us that, as they

walk along the shore or near the reefs, they often see, through clear

and shallow water, numbers of sea-slugs, some black, and some brown,

others of a dark yellow colour. These are different species of

holothuria, sought after by the natives, not so much for home, as

for foreign consumption. They are not unsightly as they creep along

their light-coloured sea-floor of sand and corals, all unconscious of

impending destiny. Some even praise their beauty. But one cannot look at

them without remembering that thousands and tens of thousands are taken

every year, drained, and split, and boiled and dried, till they become

as hard as chips; and then sent to China to be softened, and swallowed

in the rich soup of mandarin gourmands. Traders make an agreement with

some willing chief, paying him so much a hogshead for the beche-de-mer,

just as they are taken on the reef; then he sets his dependants to find

them, and to prepare suitable houses for the curing process, which keeps

many hands employed for many days.

Fijian exports, in American vessels alone, amount to

,£32,000 per annum. Those in British ships are said to be of equal

value, and Hamburgh vessels do a considerable trade.

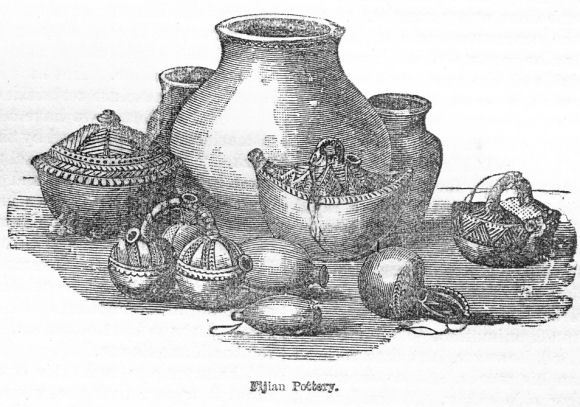

These particulars fail to give a correct idea of the

industrial produce of Fiji, which far exceeds that of other Polynesian

islands. There is an interesting chapter in the first volume of a

recently-published work, [Fiji and the Fijians. Vol. I. The Islands and

their Inhabitants. By Thomas Williams. Edited by George Stringer Rowe.

London: Hamilton and Adams.—The Editor acknowledges his obligations to

the proprietors of this work for the use of the above illustrations, and

others to appear in the continuation of this article.] which raises our

respect for the capacity and activity of the people, and shews that they

are resorted to by the Tongans and other neighbours for articles of

manufacture, pottery especially, wherein their excellence is confessed.

What has been said makes it plain that any who should

expect to find in Fiji a low type of humanity, an approach to the

physical weakness and mental incapacity of the wandering aborigines of

Australia, men whose building and cooking powers are undeveloped, would

make a great mistake. The Fijian native is a finely made man, muscular

and energetic. His house is carefully constructed, often thirty feet in

height, and from sixty to ninety feet in length, strong in posts and

rafters; its walls made of reeds neatly arranged, and adorned with

coloured sinnet-work; its thatch of long grass, or leaves of the

sugar-cane and stone-palm; with a fireplace sunk a foot below

the floor, and guarded by a kerb of hard wood; a dais serving as

a divan and sleeping-place, and a shelf for the owner's property. Many

houses, thus large and handsome, with others of inferior form and size,

are grouped into villages, intersected by narrow lanes, and protected by

reed fences. The Fijian canoe is built on so good a model that the

Tongans have adopted it in place of their own old-fashioned Togiaki.

The spears and clubs of Fiji display much skill in carving, and

speak well for the habit of patient continuance in tedious labour. In

cookery, the Fijians avail themselves of many methods; they bake, boil,

roast, and fry their food. They have twelve kinds of bread, nearly

thirty kinds of puddings, and many sorts of broths and soups, including

turtle-soup.

The language of the islands is probably richer in

radical terms than that of many other Oceanic tongues. "Whatever belongs

to their religion, their political constitution, their wars, their

social and domestic habits, their occupation and handicrafts, their

amusements, they not only express with propriety and ease, but, in many

instances, with a minuteness of representation, and a nicety of

colouring, which it is hard to reproduce in a foreign language. Thus the

Fijians can express by different words the motion of a snake and that of

a caterpillar, with the clapping of the boat lengthwise, crosswise, or

in almost any other way. For the verb 'to think' it has two words; for

'to pluck' four; for 'to carry, command, entice, lie, raise,' it has

five each; for 'to make, place, push, turn,' eight each; with fourteen

for 'to cut,' and sixteen for 'to strike.' The Greek and other

cultivated tongues have different words for 'to wash,' according as the

word has reference to the body, or to clothes and the like ; and when

the body is spoken of, their synonyms will sometimes define the limb or

part which is the subject of the action. The Fijian leaves those

languages far behind; for it can avail itself of separate terms to

express the washing process, according as it may happen to affect the

head, face, hands, feet, and body of an individual, or his apparel, his

dishes, or his floor." The people excel in conversation; and Mr Hadley,

cited by Dr Pickering, says, "In the course of much experience, the

Fijians are the only savage people I have ever met with who can give

reasons, and with whom it is possible to hold a connected conversation."

They are particular as to many points of etiquette, especially as it

regards the recognition of rank. They have an aristocratic dialect,

which hyperbolises every member of the chief's body, and the commonest

acts of his life. An armed man, when he meets a chief, lowers his arms,

takes the outside of the road, and crouches down. Should he wish to

cross the path of his superior, he must pass before and not behind him.

They have a singular custom, called bale muri, "follow in

falling." Mr Williams says—"One day I came to a long bridge, formed of a

single cocoa-nut tree, which was thrown across a rapid stream, the

opposite bank of which was two or three feet lower, so that the

declivity was too steep to be comfortable. The pole was also wet and

slippery, and thus my crossing was very doubtful. Just as I had

commenced the experiment, a heathen said, with much animation, 'To-day I

shall have a musket.' I had, however, just then to heed my steps more

than his words, and so succeeded in reaching the other side safely. When

I asked him why he spoke of a musket, the man replied, ' I felt certain

you would fall in attempting to go over, and I should have fallen after

you;' (that is, appeared to be clumsy;) ' and as the bridge is high, the

water rapid, and you a gentleman, you would not have thought of giving

me less than a musket." In their intercourse with strangers they are

almost as polite and as self-depreciating as the Chinese. They will

bring a handsome present, and say, "I have nothing fit to offer you, but

these fowls are an expression of my love for your children;" or, laying

down a valuable lot of yams —"A matter of little importance, but given

to help in fattening your hogs." Every change in health and condition is

celebrated with ceremonies and feasts. There is one custom which shews

more tenderness of feeling than we expect to find among savages. When a

girl is betrothed, and is about to leave her friends, a day is appointed

on which the relatives of her intended husband bring her trinkets, and

try to solace her, and this is called, vakama-maca, "the drying

up of the tears."

(To be continued.)