|

Few subjects possess greater interest for the

I British race than the

Scandinavian North, with its iron-bound rampart of wave-lashed rocks,

its deeply-indented fiords, bold cliffs, rocky promontories, abrupt

headlands, wild skerries, crags, rock-ledges, and caves,—all

alive with gulls, puffins, and kittiwakes; and, in short, the general

and striking picturesqueness of its scenery, to say nothing of the

higher human interest of its stirring history, and the rich treasures of

its grand old literature.

The British race has been called Anglo-Saxon; made

up, however, as it is, of many elements— ancient Briton, Roman,

Anglo-Saxon, Dane, Norman, and Scandinavian—the latter predominates so

largely over the others as to prove by evidence, external and internal,

and not to be gainsaid, that the Scandinavians are our true progenitors.

The Germans are a separate branch of the same great

Gothic family, industrious, but very unlike us in many respects. The

degree of resemblance and affinity may be settled by styling them

honest, but unenterprising, inland friends, whose ancestors and ours

were first cousins upwards of a thousand years ago.

To the old Northmen—hailing from the sea-board of

Norway, Sweden, and Denmark—may be traced the germs of all that is most

characteristic of the modern Briton, whether personal, social, or

national. The configuration of the land, and the numerous arms of the

sea with which the northwest of Europe is indented, necessitated boats

and seamanship. From these coasts, the Northmen— whether bent on

piratical plundering expeditions, or peacefully seeking refuge from

tyrannical oppression at home—sallied forth in their frail barks or

skiffs, which could live in the wildest sea, visiting and settling in

many lands. We here mention, in geographical order, Normandy, England,

Scotland, Orkney, Shetland, Faroe, and Iceland. Wherever they have been,

they have left indelible traces behind them, these ever getting more

numerous and distinct as we go northwards.

Anglen, from which the word England is derived, still

forms part of Holstein, a province of Denmark; and the preponderance of

the direct Scandinavian element in the language itself has been shewn by

Dean Trench, who states that, of a hundred English words, sixty come

from the Scandinavian, thirty from the Latin, five from the Greek, and

five from other sources.

In Scotland many more Norse words, which sound quite

foreign to an English ear, yet linger amongst the common people ; while,

as in England, the original Celtic inhabitants were driven to the west

before the Northmen, who landed on the east. In certain districts of the

Orkneys a corrupt dialect of Norse was spoken till recently, and the

Scandinavian type of features is there often to be met with.

The Norse language is still understood and frequently

spoken in Shetland, where the stalwart, manly forms of the fishermen,

the characteristic prevalence of blue eyes and light flaxen hair, the

universal observance of the Norse Yule, and many other old-world

customs, together with the oriental, and almost affecting regard paid to

the sacred rites of hospitality on the part of the islanders, all

plainly tell their origin. The language of the Faroe islanders is a

dialect of the Norse, approaching Danish, and peculiar to themselves. It

is called Faroese. The peaceful inhabitants not only resemble, but are

Northmen.

In Iceland we have pure Norse, as imported from

Norway in the ninth century, the lone northern sea having guarded it,

and many other interesting features, from those modifications to which

the Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish have been subjected by neighbouring

Teutonic or German influences. This language, the parent, or, at least,

the oldest and purest form of the various Scandinavian dialects with

which we are acquainted, has been at different times named Donsk Tunga,

Norraena, or Norse, but latterly it has been simply called Icelandic,

because peculiar to that island.

The language, history, and literature of our

ancestors having been thus preserved in the north, we are thereby

enabled to revisit the past, read it in the light of the present, and

make both subservient for good in the future.

Herodotus mentions that tin was procured from

Britain. Strabo informs us that the Phoenicians traded to our island,

receiving tin and skins in exchange for earthenware, salt, and vessels

of brass; but our first authentic particulars regarding the ancient

Britons are derived from Julius Caesar, whose landing on the southern

portion of our island, and hard-won battles, were but transient and

doubtful successes. The original inhabitants were Celts from France and

Spain; but, as we learn from him, these had long before been driven into

the interior and western portion of the island by Belgians, who crossed

the sea, made good their footing, settled on the east and south-eastern

shores of England, and were now known as Britons. With these Caesar had

to do. The intrepid bravery of the well-trained and

regularly-disciplined British warriors commanded respect, and left his

soldiers but little to boast of. The Roman legions never felt safe

unless within their entrenchments, and, even there, were sometimes

surprised. Strange to realise such dire conflicts raging at the foot of

the Surrey hills, probably in the neighbourhood of Penge, Sydenham, and

Norwood, where the Crystal Palace now peacefully stands. Even in these

dark Druid days the Britons, although clothed in skins, wearing long

hair, and stained blue with woad, were no mere painted savages, as they

have sometimes been represented, but were in possession of

regularly-constituted forms of government. They had naval, military,

agricultural, and commercial resources to depend upon, and were

acquainted with many of the important arts of life. The Briton was

simple in his manners, frugal in his habits, and loved freedom above all

things. Had the brave Caswallon headed the men of Kent, Caesar and his

hosts would never, in all likelihood, have succeeded in reaching their

ships, but would have found graves on our shores. His admirable

commentaries would not have seen the light of day, and the whole current

of Roman, nay, of the world's, history might have been changed.

Our British institutions and national characteristics

were not adopted from any quarter, completely moulded and finished, as

it were, but exhibit everywhere the vitality of growth and progress,

slow but sure. Each new element or useful suggestion, from whatever

source derived, has been tested and modified before being allowed to

take root, and form part of the constitution. The germs have been

developed in our own soil.

Thus to the Romans we can trace our municipal

institutions—subjection to a central authority, controlling the rights

of individuals. To the Scandinavians we can as distinctly trace that

principle of personal liberty which resists absolute control, and sets

limits—such as Magna Charta—to the undue exercise of authority in

governors. These two opposite tendencies, when united, like the

centripedal and centrifugal forces, keep society revolving peacefully

and securely in its orbit around the sun of truth. When severed,

tyranny, on the one hand, or democratic licence, on the other—both alike

removed from freedom—must result, sooner or later, in instability,

confusion, and anarchy. France affords us an example of the one, and

America of the other. London is not Britain in the sense that Paris is

France; while Washington has degenerated into a mere cockpit for North

and South.

From the feudal system of the Normans,

notwithstanding its abuses, we have derived the safe tenure and

transmission of land, with protection and security for all kinds of

property. British law has been the growth of a thousand years, and has

been held in so much respect that even our revolutions have been legally

conducted, and presided over by the staid majesty of justice. Were more

evidences wanting to shew that the Scandinavian element is actually the

backbone of the British race— contributing its superiority, physical and

moral, its indomitable strength and energy of character—we would simply

mention a few traits of resemblance which incontestably prove that ''the

child is father to the man."

The old Scandinavian possessed an innate love of

truth; much earnestness; respect and honour for woman; love of personal

freedom; reverence, up to the light that was in him, for sacred things;

great self-reliance, combined with energy of will to dare and do;

perseverance in overcoming obstacles. whether by sea or land; much

self-denial, and great powers of endurance under given circumstances,

These qualities, however, existed along with a pagan thirst for war and

contempt of death, which was courted on the battle-field that the

warrior might rise thence to Valhalla.

To illustrate the love of freedom, even in thought,

which characterises the race, it can be shewn that, while the Celtic

nations fell an easy prey to the degrading yoke of Romish superstition,

spreading abroad its deadly miasma from the south, the Scandinavian

nations, even when for a time acknowledging its sway, were never bound

hand and foot by it, but had minds of their own, and sooner or later

broke their fetters. In the truth-loving Scandinavian, Jesuitical Rome

has naturally ever met with its most determined antagonist; for

" True and tender is the North."

In the dark days of the Stewarts, witness the noble

struggles of the Covenanters and the Puritans for civil and religious

liberty.

Notwithstanding; mixtures and amalgamations of blood,

as a general rule the distinctive tendencies of race survive, and, good

or bad, as the case may be, reappear in new and unexpected forms. Even

habit becomes a second nature, the traces of which centuries with their

changes cannot altogether obliterate, On the other side of the Atlantic,

the Puritan Fathers, their descendants, and men like them, have been the

salt of the north; while many of the planters of the south, tainted with

cavalier blood, continue to foster slavery—"that sum of all villanies" —

and glory in being man-stealers, man-sellers, and murderers, although

cursed of God, and execrated by all right-thinking men. John Brown, who

was the other day judicially murdered, we would select as an honoured

type of the noble, manly, brave, truth-loving, God-fearing Scandinavian.

His heroism in behalf of the poor despised slave had true moral grandeur

in it—it was sublime. America cannot match it. Washington was great —

John Brown was greater. [The general opinion in this country is

that John Brown was a sincere fanatic. Very decided anti-slavery

publications in America express the same estimate of his character. We

have come to the same conclusion.—Ed, G. W.] Washington resisted the imposition of

unjust taxes on himself and his equals, but was a slaveholder; John

Brown unselfishly devoted his energies—nay, life itself—to obtain

freedom for the oppressed, and to save his country from just impending

judgments. The one was a patriot; the other was a patriot and

philanthropist. The patriotism of Washington was limited by colour; that

of Brown was thorough, and recognised the sacred rights of man. He was

hanged for trying to accomplish that which his murderers ought to have

done—nay, deserved to be hanged for not doing—hanged for that which they

shall yet do, if not first overtaken and whelmed in just and condign

vengeance; for the cry of blood ascends. He was no less a martyr to the

cause of freedom than John Brown of Priesthill, who was ruthlessly shot

by the bloody Claverhouse. These two noble martyrs, in virtue alike of

their name and cause, shall stand together on the page of future

history, when their cruel murderers have long gone to their own place.

For such deeds there shall yet be tears of blood. The wrongs of Italy

are not to be named in comparison with those of the slave. Let those who

boast of a single drop of Anglo-Saxon blood in their veins no longer

withhold just rights from the oppressed—rights which, if not yielded at

this the eleventh hour, shall be righteously, though fearfully, wrested

from the oppressors, when the hour of retribution comes; and come it

will. But we digress.

Perhaps the two most striking outward resemblances

between Britons and Scandinavians may be found in their maritime skill,

and in their powers of planting colonies, and governing themselves by

free institutions, representative parliaments, and trial by jury.

The Norse rover—bred to the sea, matchless in skill,

daring, loving adventure and discovery, and with any amount of pluck—is

the true type of the British tar. In light crafts, the Northmen could

run into shallow creeks, cross the North Sea, or boldly push off to face

the storms of the open Atlantic. These old Vikings were seasoned "salts"

from their very childhood—"creatures native and imbued unto the

element;" neither in peace nor war, on land nor sea, did they fear

anything but fear. In them we see the forerunners of the buccaneers, and the ancestors of those naval heroes,

voyagers, and discoverers—those Drakes and Dam-piers, Nelsons and

Dundonalds, Cooks and Franklins, who have won for Britain the proud

title of sovereign of the title which she is

still ready to uphold against all comers.

In Shetland, we still find the same skilled

seamanship, and the same light open boat, like a Norwegian yawl; indeed,

planks for building skiffs are generally all imported from Norway,

prepared and ready to put together. There the peace-loving fishermen, in

pursuit of their perilous calling, sometimes venture sixty miles off to

sea, losing sight of all land, except perhaps the highest peak of their

island-homes left dimly peering just above the horizon-line. Sometimes

they are actually driven, by stress of weather, within sight of the

coast of Norway, and yet the loss of a skiff in the open sea, however

high the waves run, is a thing quite unknown to the skilled Shetlander.

The buoyancy of the skiff (from this word we have ship and skipper) is

something wonderful. Its high bow and stern enables it to ride and rise

over the waves like a sea-duck, although its chance of living seems

almost as little and as perilous as that of the dancing shallop or

mussel-shell we see whelmed in the ripple. Its preservation, to the

onlooker from the deck of a large vessel, often seems miraculous. It is

the practice, in encountering the stormy blasts of the North Sea, to

lower the lug-sail on the approach of every billow, so as to ride its

crest with bare mast, and to raise it again as the skiff descends into

the more sheltered trough of the wave. By such constant manoeuvering,

safety is secured and progress made. When boats are lost—and such

tragedies frequently occur, sometimes leaving poor widows lonely, and at

one fell swoop bereft of husband, father, and brothers, for the crews

are generally made up of relatives—it is generally when, mastered by

strong currents between the islands, which neither oar nor sail can

stem, they are carried among skerries and rocks. Such losses are always

on the coasts—never at sea.

Of the Scandinavian powers of colonising: there is

ample evidence of their having settled in Shetland, Orkney, and on our

coasts, long before those great outgoings of which we have authentic

historical records. To several of these latter we shall briefly advert,

viz., the English, Russian, Icelandic, American, and Norman.

We may first mention that, in remote ages, this race

swept across Europe from the neighbourhood of the region now called

Circassia, lying between the Black Sea and the Caspian, to the shores of

the Baltic, settling on the north-west coast of Europe. Their

traditions, and numerous eastern customs, allied to the Persians and the

inhabitants of the plains of Asia Minor in old Homeric days, which they

brought along with them, all go to confirm their eastern origin. Nor did

they rest here, but, thirsting for adventure in these grim, warrior

ages, sallied forth as pirates or settlers, sometimes both, and, as we

shall now see, made their power and influence felt in every country of

Europe, from Lapland to the Mediterranean.

They invaded England in a.d. 429, and founded the

kingdoms of South, West, and East Seaxe, East Anglia, Mercia, Deira, and

Bernicia; thus

overrunning and fixing themselves in the land, from

Devonshire to north of the Humber. From the mixture of these Angles, or

Saxons, as they were termed by the Britons, with the previous Belgian

settlers and original inhabitants, we have the Anglo-Saxon race. The

Jutes who settled in Kent were from Jutland. In A.D. 787, the Danes

ravaged the coast, beginning with. Dorsetshire; and, continuing to swarm

across the sea, soon spread themselves over the whole country. They had

nearly mastered it all, when Alfred ascended the throne in 871. At

length, in A.D. 1017, Canute, after much hard fighting, did master it,

and England had Danish kings from that period till the Saxon line was

restored in 1042.In the year A.D. 862, the

Scandinavian Northmen established the Russian empire, and played a very

important part in the management of its affairs even after the

subsequent infusion of the Sclavonic element. In the "Memoires de la

Societe Royale des Antiquaires du Nord," published at Copenhagen, we

find that, of the fifty names of those composing Ingor's embassy to the

Greek Emperor at Constantinople in the year A.D. 994, only three were

Sclavic, and the rest Northmen— names that occur in the Sagas, such as

Ivar, Vig-fast, Eylif, Grim, Ulf, Frode, Asbrand, &c. The Greeks called

them Russians, and Frankish writers simply Northmen.

In the year A. D. 863, Naddodr, a Norwegian,

discovered Iceland, [The antiquarian book to which we have already

referred, erroneously attributes the discovery to Garder, a Dane of

Swedish origin. Our authority is Gisli Brynjulfsson, the Icelandic poet,

now resident in Copenhagen, to whose kindness we are indebted for the

copy which we possess.] which, however, had been previously visited and

resided in at intervals for at least upwards of seventy years before

that time, by fishermen, ecclesiastics, and hermits, called West-men,

and thought to be from Ireland. Of these visits Naddodr found numerous

traces.

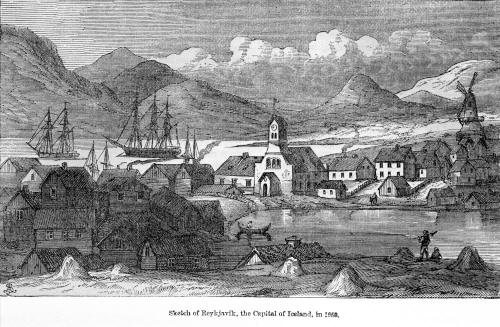

In A.D. 874, Ingolf with his followers, many of whom

were related to the first families in Norway, fleeing from the tyranny

of Harold Harfagra, began the colonisation of Iceland, which was

completed during a space of sixty years. They established a flourishing

republic, appointed magistrates, and held their Althing, or annual

national assembly, at Thingvalla. Thus, in this distant volcanic island

of the Northern Sea, the old Danish language was preserved unchanged for

centuries; while, in the various eddas, were embodied those folk - songs

and folk - myths, and, in the sagas, those historical tales and legends

of an age at once heroic and romantic, together with that folk-lore

which still forms the staple of all our old favourite nursery tales, and

was brought with them from Europe and the East by the first settlers,

[For these last we would refer to Thorpe's "Yule-, tide Stories,"

Dasent's "Popular Tales from the Norse," and to our own nursery lore.]

All these, as well as the productions of the Icelanders themselves, are

of great historical and literary value. They have been carefully edited

and published, at Copenhagen, by eminent Icelandic, Danish, and other

antiquarians. We would refer to the writings of Muller, Magnusen, Rafn,

Rask, Eyricksson, Torfaeus, and others. Laing has translated "The

Heimskringla," the great historical saga of Snorre Sturleson, into

English. Various other translations and accounts of these

singularly-interesting eddas, sagas, and ballads, handed down by the

Scalds and Sagamen, are to be met with; but by far the best analysis,

with translated specimens, is that contained in Howitt's "Literature of

the North of Europe." We would call attention, in passing, to the edda,

consisting of the original series of tragic poems from which the German

"Niebelungenlied" has been derived, as a marvellous production,

absolutely unparalleled in ancient or modern literature, for power,

simplicity, and heroic grandeur.

Christianity was established in Iceland in the year

1000. Fifty-seven years later, Isleif, Bishop of Skalholt, first

introduced the art of writing the Roman alphabet, thus enabling them to

fix oral lessons of history and song; for the Runic characters

previously in use were chiefly employed for monuments and memorial

inscriptions, and were carved on wood-staves, on stone or metal. On

analysis, these rude letters will be found to be crude forms and

abridgments of the Greek or Roman alphabet. We have identified them all,

with the exception of a few letters, and are quite satisfied on this

point, so simple and obvious is it, although we have not previously had

our attention directed to the fact.

Snorre Sturleson was perhaps one of the most learned

and remarkable men that Iceland has produced.

In 1264, through fear and fraud, the island submitted

to the rule of Haco, king of Norway:— he

who died at Kirkwall, after his forces were routed by the Scots at the

battle of Largs. In 1387, along with Norway, it became subject to

Denmark. In 1529 a printing press was established; and in 1550 the

Lutheran Reformation was introduced into the island—the form of worship

which is still retained.

True to the instinct of race, the early settlers in

Iceland did not remain inactive, but looked westward, and found scope

for their hereditary maritime' skill in the discovery and colonising of

Greenland. They also discovered Helluland (Newfoundland), Markland (Nova

Scotia), and Vineland (New England). They were also acquainted with

American land, which they called Hvitramannaland, (the land of the white

men,) thought to have been North and South Carolina, Georgia, and

Florida. We have read authentic records of these various voyages,

extending from a.d. 877 to A.D. 1347. The names of the principal

navigators are Gunn-biorn, Eric the Red, Biarne, Leif, Thorwald, &c. But

the most distinguished of these American discoverers is Thorfinn

Karlsefne, an Icelander, "whose genealogy," says Rafn, "is carried back,

in the old northern annals, to Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Scottish, and

Irish ancestors, some of them of royal blood." With singular interest we

also read that, "in A.D. 1266, some priests at Gardar, in Greenland, set

on foot a voyage of discovery to the arctic regions of America. An

astronomical observation proves that this took place through Lancaster

Sound and Barrow's Strait to the latitude of Wellington's Channel."

When Columbus visited Iceland in A.D. 1467, ha may

have obtained confirmation of his theories as to the existence of a

great continent in the west; for these authentic records prove the

discovery and colonisation of America by the Northmen from Iceland

upwards of five hundred years before he rediscovered it.

The Norman outgoing is the last we shall here allude

to. In A.D. 876 the Northmen, under Rollo, wrested Normandy from the

Franks; and from thence, in A.D. 1065, "William, sprung from the same

stock, landed at Hastings, vanquished Harold, and is known to this day

as the Conqueror of England. It was a contest of Northmen with Northmen,

where diamond cut diamond.

Instead of one article, this subject, we feel, would

require a volume. At the outset we asserted that northern subjects

possessed singular interest for the British race. In a very cursory

manner we have endeavoured to prove it, by shewing that, to Scandinavia,

as its cradle, we must look for the germs of that spirit of enterprise

which has peopled America, raised an Indian empire, and colonised

Australia, and which has bound together as one, dominions on which the

sun never sets; all, too, either speaking, or fast acquiring, a noble

language, which bids fair one day to become universal.

The various germs, tendencies, and traits of

Scandinavian character, knit together and amalgamated in the British

race, go to form the essential elements of greatness and success, and,

where sanctified and directed into right channels, are noble materials

to work upon.

It is Britain's pride to be at once the mistress of

the seas, the home of freedom, and the sanctuary of the oppressed. May

it also be her high honour, by wisely improving outward privileges, and

yet further developing her inborn capabilities, pre - eminently to

become the torch-bearer of pure Christianity — with its

ever-accompanying freedom and civilisation—to the whole world!

|