|

IN 1798 the condition and

characteristics of the parishioners of Alvie are thus described:—

“The inferior tenants are poor, and their habitations wretchedly

comfortless; their farms are small, from £2 to £6 sterling of yearly rent,

and their land may be let from 5s. to 10s. the acre. The crops, consisting

of oats, rye, barley, and potato, are in general sufficient for the

subsistence of the inhabitants. The parish abounds with fir, birch, alder,

and a few oaks; carried by the poorer people 40 miles to the nearest market

towns in small parcels, and sold to procure the few necessaries they desire.

There is only one farm stocked wholly with sheep; the whole of that stock in

the parish amounts to 7000, the black cattle to 1104, the horses to 510, and

there are 101 ploughs. . . . The people have little idea of trade or

manufactures, excepting a considerable quantity of a coarse kind of flannel

called plaiding or blankets, sold for about iod. the ell of 39 inches.

Although all disputes are settled by the Justice of the Peace, without

recourse to the Sheriff or other Judge, . . . they have no inclination to

leave the spot of their nativity, and if they can obtain the smallest

pendicle of a farm, they reject entering into any service, and are extremely

averse to that of the military. They are fond of dram-drinking, and

squabbles are not infrequent at burials or other meetings. Few of the older

people can read, and they are rather ignorant of the principles of religion.

There are 2 retail shops, 6 weavers, 4 taylors, 2 blacksmiths, and 2 who

make the brogue shoes worn by the poorer people. . . . The great road from

Inverness to Edinburgh is conducted up the north side of the Spey for the

whole length of the parish; it passes through a number of little heaps or

piles of stone and earth, opposite to the church : the most conspicuous one

was lately opened; the bones entire of a human body were found in their

natural order, with two large hart horns laid across.”

In the immediate neighbourhood of the church and manse of Alvie is beautiful

Kinrara—surely one of the most lovely spots on earth—with its memorable

associations of the celebrated Jane, Duchess of Gordon, and her brilliant

coterie.

“Though many splendid landscapes,” says the fastidious Macculloch, “are

obtained along the roadside between Aviemore and Kinrara, constituted by the

far-extended fir-woods of Rothiemurchus, the ridge of Cairngorm, the

birch-clad hill of Kinrara, and by the variety of the broken, bold, and

woody banks of the Spey, no one can form an adequate idea of the beauties of

this tract without spending days in investigating what is concealed from an

ordinary and passing view. By far the larger proportion of this scenery,

also, is found near to the river, and far from the road; and the most

singular portions of it lie on the east side of the water, and far beyond it

in places seldom trodden and scarcely known. This, too, is a country

hitherto undescribed, and therefore unseen by the mass of travellers, though

among the most engaging parts of the Highlands, as it is the most singular;

since there is nothing with which it can be compared, or to which indeed it

can be said to bear the slightest resemblance. Much of this depends on the

peculiar forms and distribution of the ground and of the mountains, and

still more on the character of the wood, which is always fir and birch, the

latter in particular assuming a consequence in the landscape which renders

the absence of all other trees insensible, and which is seen nowhere in the

same perfection, except at Blair and for a short space along the course of

the Tummel. Of this particular class of beauty, Kinrara is itself the chief

seat, yielding to very few situations in Scotland for that species of

ornament which, while it is the produce of Nature, seems to have been guided

by Art, and being utterly distinguished from the whole in character. A

succession of continuous birch - forest, covering its rocky hill and its

lower grounds, intermixed with open glades, irregular clumps, and scattered

trees, produces a scene at once Alpine and dressed, combining the discordant

characters of wild mountain landscape and of ornamental park scenery. To

this it adds an air of perpetual spring, and a feeling of comfort and of

seclusion which can nowhere be seen in such perfection, while the range of

scenery is at the same time such as is only found in the most extended

domains. If the home grounds are thus full of beauties, not less varied and

beautiful is the prospect around, the Spey, here a quick and clear stream,

being ornamented by trees in every possible combination, and the banks

beyond rising into irregular, rocky, and wooded hills, everywhere rich with

an endless profusion of objects, and as they gradually ascend displaying the

dark sweeping forests of fir that skirt the bases of the further mountains,

which terminate the view of their bold outlines on the sky. ... To wander

along the opposite banks is to riot in a profusion of landscape always

various and always new, river scenery of a character unknown elsewhere, and

a spacious valley crowded with objects and profuse of wood, displaying

everywhere a luxuriance of variety as well in the disposition of its parts

as in the arrangements of its trees and forests and the versatility of its

mountain boundary.” In her girlhood days Duchess Jane was an incorrigible,

but withal a most bewitching, lovable romp, and apparently she retained her

exuberant spirits down almost to the close of her life. Here is a very

amusing picture of her early life in the High Street of Edinburgh, then the

most fashionable quarter in the Scottish metropolis. “In Hyndford’s Close,

near the bottom of the High Street—first entry in the close, and second door

upstairs—dwelt about the beginning of the reign of George III., Lady Maxwell

of Monreith, and there brought up her beautiful daughters, one of whom

became Duchess of Gordon. The house had a dark passage, and the kitchen-door

was passed in going to the diningroom, according to an agreeable old

practice in Scotch houses, which lets the guests know on entering what they

have to expect. The fineries of Lady Maxwell’s daughters were usually hung

up, after washing, on a screen in this passage to dry; while the coarser

articles of dress, such as shifts and petticoats, were slung decently out of

sight at the window upon a projecting contrivance, similar to a dyer’s pole,

of which numerous specimens still exist at windows in the Old Town for the

convenience of the poorer inhabitants. So easy and familiar were the manners

of the great in those times, fabled to be so stiff and decorous, that Miss

Eglintoune, afterwards Lady Wallace, used to be sent with the tea-kettle

across the street to the Fountain well for water to make tea. Lady Maxwell’s

daughters were the wildest romps imaginable. An old gentleman, who was their

relation, told me that the first time he saw these beautiful girls was in

the High Street, where Miss Jane, afterwards Duchess of Gordon, was riding

upon a sow, which Miss Eglintoune thumped lustily behind with a stick. It

must be understood that, sixty years since, vagrant swine went as commonly

about the streets of Edinburgh as dogs do in our own day, and were more

generally fondled as pets by the children of the last generation. It may,

however, be remarked that the sows upon which the Duchess of Gordon and her

witty sister rode, when children, were not the common vagrants of the High

Street, but belonged to Peter Ramsay of the Inn in St Mary’s Wynd, and were

among the last that were permitted to roam abroad. The two romps used to

watch the animals as they were let loose in the forenoon from the

stable-yard (where they lived among the horse-litter), and get upon their

backs the moment they issued from the close.”

In the “Seaforth Papers,” as

published in the ‘North British Review,’ the life of the Duchess is thus

noticed: “Early in life, Alexander, the fourth Duke of Gordon, married Jane

Maxwell, ‘The Flower of Galloway,’ and a handsomer couple has rarely been

seen. The Duke was in his twenty-fourth year, the bride in her twenty-first.

Reynolds has preserved some memorial of the youthful beauty of the Duchess,

and a lovelier profile was never drawn. As a girl she was strongly attached

to a young officer, who reciprocated her passion. The soldier, however, was

ordered abroad with his regiment, and shortly afterwards was reported dead.

This was the first great calamity that Jane Maxwell experienced; and after

the first burst of grief had spent itself, she sank into a state of

listlessness and apathy that seemed immovable. But the Duke of Gordon

appeared as a suitor, and, partly from family pressure, partly from

indifference, Jane accepted his hand. On their marriage tour the young pair

visited Ayton House in Berwickshire, and there the Duchess received a letter

addressed to her in her maiden name, and written in the well-known hand of

her early lover. He was, he said, on his way home to complete their

happiness by marriage. The wretched bride fled from the house, and,

according to the local tradition, was found, after long search, stretched by

the side of a burn, nearly crazed. When she had recovered from this terrible

blow and re-entered society, Jane presented an entirely new phase of

character. She plunged into all sorts of gaiety and excitement ; she became

famous for her wild frolics and for her vanity and ardour as a leader of

fashion; her routs and assemblies were the most brilliant of the capital,

attracting wits, orators, and statesmen.”

In a letter to a friend, of date 4th July 1798, Mrs Grant of Laggan gives a

very suggestive glimpse of the active habits of the Duchess while resident

at Kinrara: “The Duchess of Gordon is a very busy farmeress at Kinrara, her

beautiful retreat on the Spey some miles below this. She rises at five in

the morning, bustles incessantly, employs from twenty to thirty workmen

every day, and entertains noble travellers from England in a house very

little better than our own, but she is setting up a wooden pavilion to see

company in.” In a subsequent letter Mrs Grant says that, “unlike most people

of the world,” the Duchess “presentejd her least favourable phases to the

public; but in this her Highland home, all her best qualities were in

action, and there it was that her warm benevolence and steady friendship

were known and felt.”

Near the close of last century rumours' of a French invasion alarmed the

country and roused military ardour to such an extent as to lead to fresh

regiments being raised. In one of a series of very interesting sketches by

the Honourable Mrs Armytage of “British Mansions and their Mistresses past

and present,” recently published in ‘Tinsley’s Magazine,’ the raising by the

famous Duchess of the battalion of Gordon Highlanders, which has since held

such a distinguished place in our military annals, is thus described: “The

Duchess is said to have had a wager with the Prince Regent as to which of

them would first raise a battalion, and that the fair lady reserved to

herself the power of offering a reward even more attractive than the king’s

shilling. At all events the Duchess and Lord Huntly started off on their

errand, and between them soon raised the required number of men. The mother

and son frequented every fair in the country-side, begging the fine young

Highlanders to come forward in support of king and country, and to enlist in

her regiment; and when all other arguments had failed, rumour stated that a

kiss from the beautiful Duchess won the doubtful recruit. She soon announced

to headquarters the formation of a regiment, and entered into all the

negotiations with the military authorities in a most business-like manner,

reporting that the whole regiment were Highlanders save thirty-five. Lord

Huntly was given the first command of this corps, then and ever since known

as the g2d or Gordon Highlanders, and wearing the tartan of the Clan.”

In 1799, Lord Huntly—then in his twenty-ninth year—accompanied the regiment

to Holland under the gallant Sir Ralph Abercrombie. Mrs Grant of Laggan

composed on the occasion the following song, which has since been so popular

as sung to the air of “The Blue - Bells of Scotland” :—

“Oh, where, tell me where, is your Highland Laddie gone?

Oh, where, tell me where, is your Highland Laddie gone?

He’s gone with streaming banners, where noble deeds are done,

And my sad heart will tremble till he come safely home.

He’s gone with streaming banners, where noble deeds are done,

And my sad heart will tremble till he come safely home.

Oh, where, tell me where, did

your Highland Laddie stay?

Oh, where, tell me where, did your Highland Laddie stay?

He dwelt beneath the holly-trees, beside the rapid Spey,

And many a blessing followed him the day he went away.

He dwelt beneath the holly-trees, beside the rapid Spey,

And many a blessing followed him the day he went away.

Oh, what, tell me what, does your Highland Laddie wear?

Oh, what, tell me what, does your Highland Laddie wear?

A bonnet with a lofty plume, the gallant badge of war,

And a plaid across the manly breast that yet shall wear a star.

A bonnet with a lofty plume, the gallant badge of war,

And a plaid across the manly breast that yet shall wear a star.

Suppose, ah, suppose, that some cruel, cruel wound

Should pierce your Highland Laddie, and all your hopes confound

The pipe would play a cheering march, the banners round him fly,

The spirit of a Highland Chief would lighten in his eye.

The pipe would play a cheering march, the banners round him fly,

And for his king and country dear with pleasure he would die!

But I will hope to see him yet in Scotland’s bonny bounds :

But I will hope to see him yet in Scotland’s bonny bounds,

His native land of liberty shall nurse his glorious wounds,

While wide through all our Highland hills his warlike name resounds!

His native land of liberty shall nurse his glorious wounds,

While wide through all our Highland hills his warlike name resounds.”

“There is no doubt,” says Mrs Armytage, “that the welfare of her husband’s

tenants was a matter of great concern to the Duchess, and that she devoted

much of her time and energy to all matters connected with the improvement

and happiness of her Scotch people. She and the Duke exercised unbounded

hospitality, and both loved to be surrounded by philosophers, politicians,

poets, and scholars, all of whom professed unbounded admiration of her

beauty, the brilliancy of her wit, and her cultivated understanding.”

The poet Burns characterised the Duchess as “charming, witty, kind, and

sensible.” In 1780 Dr Beattie thus addressed her in verse when sending a pen

for her use :—

“Go and be guided by the brightest eyes,

And to the softest hand thine aid impart

To trace the fair ideas as they rise

Warm from the purest, gentlest, noblest heart.”

And in a letter addressed to herself, he is equally lavish of praise,

saying: “Your Grace’s heart is already too feelingly alive to each fine

impulse; to you I would recommend gay thoughts, cheerful books, and

sprightly company—I might have said company without limitation, for wherever

you are, the company must be sprightly. I rejoice in the good weather and

the belief that it extends to Glenfiddich, where I pray that your Grace may

enjoy all the health and happiness that good air, goat’s whey, romantic

solitude, and the society of the loveliest children in the world can

bestow.”

Whatever the enjoyment of the quiet life in the Highlands may have been, it

certainly was a strange contrast to the days spent in London, one of which

has been thus described by Walpole to a correspondent (Miss Berry) in 1791:

“ One of the Empresses of fashion, the Duchess of Gordon, uses fifteen or

sixteen hours of her four-and-twenty. I heard her Journal of last Monday.

She went first to Handel’s music in the Abbey; she then clambered over the

benches and went to Hasting’s trial in the Hall; after dinner to the play,

then to Lord Lucan’s assembly; after that to Ranelagh, and returned to Mrs

Hobart’s faro-table; gave a ball herself in the evening of that morning into

which she must have got a good way; and set out for Scotland next day.

Hercules could not have achieved a quarter of her labours in the same space

of time.”

As the old proverb has it, “The sleeping fox catches no poultry,” and if one

might venture with “bated breath to point a moral and adorn a tale,” it

would be to whisper that the example of the “noble Jane,” as regards early

rising and busy habits in the matter of farming, might with advantage be

followed to a greater extent, not only by farmers and “farmeresses,” big and

small, but by many young men and maidens in the Highlands in the present

day. The Duchess died at London in 1812, survived by her husband, Alexander,

the fourth Duke of Gordon, a son, and five daughters. A noteworthy fact in

the life of Duke Alexander is that he enjoyed the honours of the family for

the long period of seventy-five years—namely, from 1752 down to his death in

1827—a fact probably unexampled in the annals of the Scottish peerage. The

family estates were at one time of vast dimensions, extending as they did

from sea to sea, winding across the entire breadth of the country between

the Atlantic and the German Ocean. In the last century a learned historian

of the family dedicated the first of his two volumes to Duke Alexander in

the following terms: “To the High, puissant, and noble Prince Alexander,

Duke of Gordon, Marquis of Huntly, Earl of Huntly and Enzie, Viscount of

Inverness, Lord Gordon of Badenoch, Lochaber, Strathavin, Balmore,

Auchindoun, Gartly, and Kincardine.” The greater portion of Badenoch then

belonged to the family, and the kindness and liberality extended to the

people of the district by Duke Alexander during his long and beneficent

sway, and subsequently by his son (the fifth and last Duke), were nothing

short of princely in their munificence. The beautiful verses composed on the

occasion of the death of Duchess Jane, by the venerable Mrs Allardyce of

Cromarty, are worth quoting:—

“Fair in Kinrara blooms the rose,

And softly waves the drooping willow,

Where beauty’s faded charms repose,

And splendour rests on earth’s cold pillow.

Her smile, who sleeps in yonder bed,

Could once awake the soul to pleasure,

When fashion’s airy train she led,

And formed the dance’s frolic measure.

When war called forth our youth to arms,

Her eye inspired each martial spirit;

Her mind, too, felt the Muse’s charms,

And gave the meed to modest merit.

But now farewell, fair northern star !

Thy beams no more shall courts enlighten ;

No more lead forth our youth to war,

No more the rural pastimes brighten.

Long, long thy loss shall

Scotia mourn;

Her vales which thou wert wont to gladden

Shall long look cheerless and forlorn,

And grief the Minstrel’s music sadden ;

And oft amid the festive scene,

Where pleasure cheats the midnight pillow,

A sigh shall breathe for noble Jane,

Laid low beneath Kinrara’s willow!”

“A week,” says Macculloch, “spent at Kinrara had not exhausted the half of

its charms; and when a second week had passed, all seemed still new. But

time flew, never to return; for I had scarcely taken my leave of its lovely

scenes, when the mind that inspired it was fled, and the hand that had

tended and decked it was cold. That was a loss indeed.

“The sunshine that slept on Cairngorm, gave beauty even to its barren and

torrid surface, and the waste and vacant expanse smiled to the wide azure of

a cloudless sky. Still brighter was that sun and bluer were those skies

beneath the influence of other smiles, and even the arid rock and the misty

desert seemed to breathe of loveliness and spring. A single mind animated

all the landscape,—that mind which animated all it reached, which diffused

happiness around, the joy and delight of all. Yet the happiest, like the

most wretched hours, must end. That day fled fast indeed. But I did not then

foresee that for Her, that blooming and youthful, that intellectual and

lovely being, who seemed born to be a light and a blessing to all around

her, the record which this useless hand is now writing would be written in

vain. We ascended the hill together, we looked together for Craig Ellachie

and Tor Alvie. Often have I seen Tor Alvie since; but she can see it no

more.”

Mr Duncan Macpherson, Kingussie, the venerable “Old Banker”— who died in

February 1890 at the ripe old age of ninety-one—vividly described the

intense interest excited in Badenoch by the arrival of the remains of the

Duchess in a hearse drawn all the way from London by six jet-black Belgian

horses. At Dalwhinnie, the first stage within the wide Highland

territory—then belonging to the family—at which the funeral cortege arrived,

the body of the Duchess lay in state for two days. For a similar period it

lay at the inn then at Pitmain, within half a mile of Kingussie, and was

subsequently followed by an immense concourse of Highland people to the

final resting-place at her beloved Kinrara. According to her own directions,

her remains were interred in a favourite sequestered spot within a short

distance from Kinrara House, far away from the noise of the “ great Babylon

” in which she died, and within hearing of the plaintive song of our noble

Highland river, to which the Highland-loving muse of Professor Blackie has

given such beautiful and appropriate expression :—

“From the treeless brae

All green and grey

To the wooded ravine I wind my way,

Dashing and foaming and leaping with glee,

The child of the mountain wild and free,

Under the crag where the stonecrop grows,

Fringing with gold my shelvy bed,

Where over my head

Its fruitage of red

The rock-rooted rowan-tree blushfully shows,

I wind till I find

A way to my mind ;

While hazel and oak and the light ash-tree

Weave a green awning of leafage for me ;

Slowly and smoothly my winding I make

Round the dark-wooded islets that stud the clear lake ;

The green hills sleep

With their beauty in me,

Their shadows the light clouds Fling as they flee,

While in my pure waters pictured I glass

The light-plumed birches that nod as I pass.”

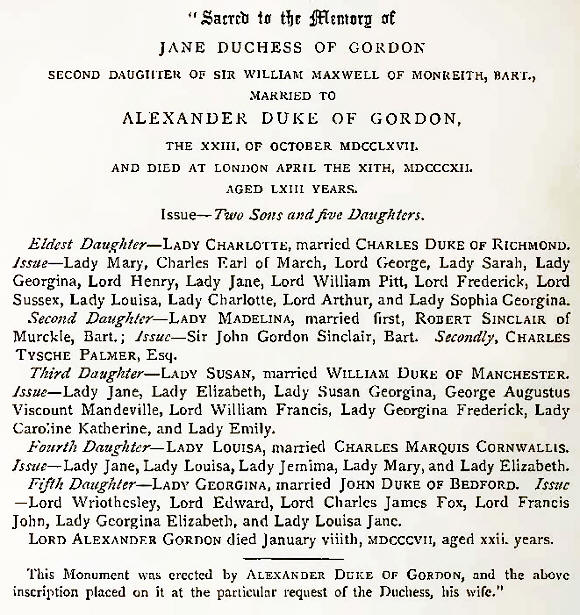

The spot where the Duchess is buried is marked by a granite monument erected

by her husband. With the pardonable pride of the mother of such a bevy of

fair daughters—to whose attractions, combined with her own winning steering

of the one after the other into the matrimonial haven, three Dukes, a

Marquis, and a Baronet had succumbed—she had herself prepared the

inscription to be placed on the monument. That inscription, as regards the

marriages and issue of her five daughters, is so remarkable that I cannot

refrain from quoting it:—

“Duke Alexander,” says Dr

Carruthers, “was a man of taste and talent, and of superior mechanical

acquirements. He wrote some good characteristic Scotch songs in the minute

style of painting local manners, and he wrought diligently at a

turning-lathe! He was lavish of snuff-boxes of his own manufacture, which he

presented liberally to all his friends and neighbours. On one occasion he

made a handsome gold necklace, which he took with him to London and

presented to Queen Charlotte. It was so much admired in the Royal circle

that the old Duke used to say with a smile he thought it better to leave

town immediately for Gordon Castle lest he should get an order to make one

for each of the Princesses! His son, the' gay and gallant Marquis of Huntly

(the fifth Duke, and “the last of his race”), was a man of different mould :

he had nothing mechanical, but was the life and soul of all parties of

pleasure. There certainly never was a better chairman of a festive party. He

could not make a set speech; and on one occasion when Lord Liverpool asked

him to move or second an address at the opening of a session of Parliament,

he gaily replied that he would undertake to please all their Lordships if

they adjourned to the City of London Tavern, but he could not undertake to

do the same in the House of Lords. He excelled in short unpremeditated

addresses, which were always lively and to the point. We heard him once on

an occasion which would have been a melancholy one in any other hands. He

had been compelled to sell the greater part of his property in the district

of Badenoch to lessen the pressure of his difficulties and emancipate

himself in some measure from legal trustees. The gentlemen of the district

resolved before parting with their noble landlord to invite him to a public

dinner in Kingussie. A piece of plate or some other mark of regard would

perhaps have been more apropos, and less painful in its associations; but

the dinner was given and received, champagne flowed like water, the

Highlanders were in the full costume of the mountains, and great excitement

prevailed. When the Duke stood up, his tall graceful form slightly stooping

with age, and his gray hairs shading his smooth bald forehead, with a

General’s broad riband across his breast, the thunders of applause were like

a warring cataract or mountain torrent in flood. Tears sparkled in his eyes,

and he broke out with a hasty acknowledgment of the honours paid to him. He

alluded to the time when he roamed their hills in youth gathering recruits

among their mountains for the service of his country, of the strong

attachment which his departed mother entertained for every cottage and

family among them, and of his own affection for the Highlands, which he said

was as firm and lasting as the Rock of Cairngorm, which he was still proud

to possess. The latter was a statement of fact: in the sale of the property

the Duke had stipulated for retaining that wild mountain-range called the

Cairngorm Rocks. The effect of this short and feeling speech—so powerful is

the language of nature and genuine emotion — was as strong as the most

finished oration could produce.”

The following delightful

“glimpse” of the life of the last Duke and _ 1 Highland Note-Book, 119, 120.

Duchess at Gordon Castle, the chief seat of the family, was given by an

American writer, N. P. Willis, in 1833 :—

“The immense iron gate surmounted by the Gordon arms, the handsome and

spacious stone lodges on either side, the canonically fat porter in white

stockings and gay livery, lifting his hat as he swang open the massive

portal, all bespoke the entrance to a noble residence. The road within was

edged with velvet sward, and rolled to the smoothness of a terrace walk; the

winding avenue lengthened away before with trees of every variety of

foliage; light carriages passed me driven by ladies or gentlemen bound on

their afternoon airing; keepers with hounds and terriers, gentlemen on foot

idling along the walks, and servants in different liveries hurrying to and

fro, betokened a scene of busy gaiety before me. I had hardly noted these

varied circumstances before a sudden curve in the road brought the castle

into view, a vast stone pile with castellated wings, and in another moment I

was at the door, where a dozen powdered footmen were waiting on a party of

ladies and gentlemen to their several carriages. ... I passed the time till

the sunset looking out on the park. Hill and valley lay between my eye and

the horizon; sheep fed in picturesque flocks, and small fallow-deer grazed

near them; the trees were planted and the distant forest shaped by the hand

of taste; and broad and beautiful as was the expanse taken in by the eye, it

was evidently one princely possession. A mile from the castle wall the

shaven sward extended in a carpet of velvet softness as bright as emerald,

studded by clumps of shrubbery, like flowers wrought elegantly on tapestry,

and across it bounded occasionally a hare, and the pheasants fed undisturbed

near the thickets.

. . . This little world of enjoyment, luxury, and beauty lay in the hand of

one man, and was created by his wealth in these northern wilds of Scotland.

... I never realised so forcibly the splendid results of wealth and

primogeniture. ... I was sitting by the fire imagining forms and faces for

the different persons who had been named to me when there was a knock at the

door, and a tall white-haired gentleman of noble physiognomy, but singularly

cordial address, entered with a broad red ribbon across his breast, and

welcomed me most heartily to the castle.

. . . The Duchess, a tall and very handsome woman, with a smile of the most

winning sweetness received me at the drawing-room door, and I was presented

successively to every person present. Dinner was announced immediately, and

the difficult question of precedence being sooner settled than I had ever

seen it before in so large a party, we passed through files of servants to

the dining-room. It was a large and very lofty hall, supported at the end by

marble columns. The walls were lined with full-length family pictures from

old knights in armour to the modern dukes in kilt of the Gordon plaid, and

on the sideboards stood services of gold plate, the most gorgeously massive

and the most beautiful in workmanship I have ever seen. There were among the

vases several large coursing-cups won by the Duke’s hounds of exquisite

shape and ornament. . . . The Jacobite songs with their half-warlike,

half-melancholy music were favourites of the Duchess of Gordon, who sang

them in their original Scotch with great enthusiasm and sweetness. The aim

of Scotch hospitality seems to be to convince you that the house and all

that is in it is your own, and you are at liberty to enjoy it as if you

were, in the sense of the French phrase, chez vous. The routine of Gordon

Castle was what each one chose to make it. . . . The number at the

dinner-table was seldom less than thirty, but the company was continually

varied by departures and arrivals—no sensation was made by either one or the

other. A travelling carriage drove to the door, was disburdened of its load,

drove round to the stables, and the question was seldom asked,

‘Who is arrived?’ You are sure to see at dinner, and an addition of

half-a-dozen to the party made no perceptible difference in anything.”

The dukedom of Gordon became, as is well known, extinct on the death of

George, the fifth Duke, without issue, in 1836. The Kinrara property then

devolved upon his nephew, the fifth Duke of Richmond, the eldest son of

Duchess Jane’s eldest daughter, and is now in possession of her

great-grandson, the present Duke of Richmond, in the person of whom the old

dukedom of Gordon was revived, and the new earldom of Kinrara so deservedly

bestowed in 1876. Patriotic nobleman and estimable landlord as he is

universally acknowledged to be, it would, I believe, be extremely gratifying

to all classes in the district if, as the great-grandson of her “who sleeps

in yonder bed,” he would occasionally reside at Kinrara, where, “ alone with

nature’s God,” all that is mortal of his famous relative so quietly and

peacefully rests. Devotedly attached as the Duchess was to the Highlands and

the Highland people, and ever giving, as she did, “the meed to modest

merit,” her memory is still gratefully cherished in Badenoch.

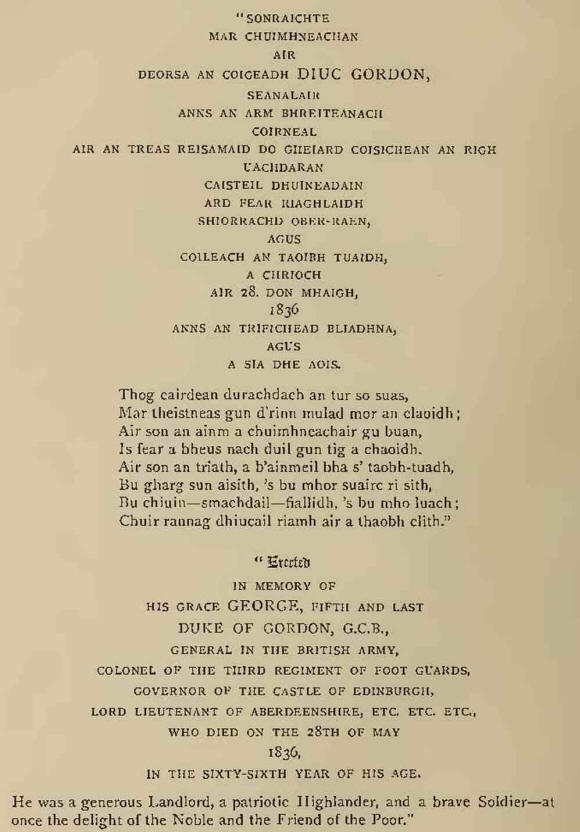

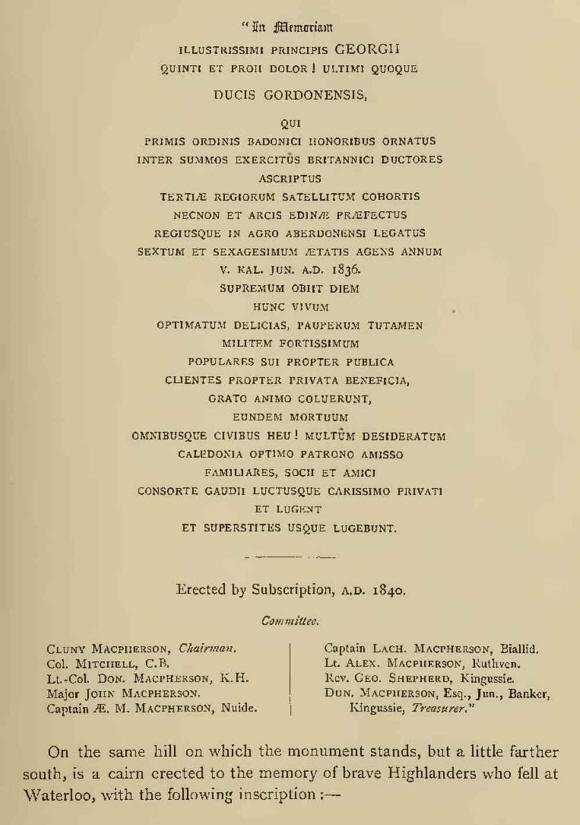

On the summit of Kinrara Hill is the monument to the last Duke of Gordon, a

landmark seen far and wide, with the following inscriptions in Gaelic,

English, and Latin, viz.:—

The last Duke of Gordon, it

is said, used the interior of this cairn as a wine-cellar for the benefit of

picnic parties whom he brought to the spot, and the strong copper door

remains as securely fastened as the door of a famous wine-cellar in

Edinburgh belonging to a well-known total abstainer. In 1819, Prince

Leopold, afterwards King of the Belgians, visited Kinrara, and at the

banquet given on the occasion the Duke, then Marquis of Huntly, is said to

have sounded a whistle, and, to the surprise of the company, up from the

heather, where their presence never had been suspected, sprang a company of

kilted Highland warriors.

' Their chieftain stood with eagle-plume, But they, with mantles folded

round, Were couched to rest upon the ground, Scarce to be known by curious

eye From the deep heather where they lie; So well was matched the tartan

screen With heath-bell dark and brackens green. The mountaineer then

whistled shrill, And he was answered from the hill; Instant, through copse

and heath, arose Bonnets and spears and bended bows ;

And every tuft of broom gave life To plaided warrior armed for strife !

Watching their leader’s beck and will,

All silent there they stood and still.

Short space he stood, then raised his hand To his brave clansman’s eager

band ; Then shout of welcome shrill and wide, Shook the steep mountain’s

steady side; Thrice it arose, and brake, and fell, Three times gave back the

martial yell.”

“Ah,” exclaimed the Prince, surprised and highly pleased, “we’ve got

Roderick Dhu here!”

At a ball given at Kinrara in honour of Prince Leopold’s visit it is related

that the widow of Mackintosh of Borlum was present, and that the Prince was

quite delighted with her quaint racy conversation. When her “carriage” was

announced, one of the Prince’s aides-de-camp stepped forward and offered his

arm. She hesitated a moment, and then said with an air of resignation,

“Well, well, I suppose you’ll have to see it.” He returned in fits of

laughter, for the old lady’s carriage was a common cart with a wisp of straw

in the middle for a seat.

In the ‘Home Life of Sir David Brewster,’ by his gifted daughter, Mrs

Gordon—so well known as the authoress of many popular works— we are told

that even while giving play to his characteristic passion of reforming

abuses, he “ awakened a warm and abiding attachment amongst the majority of

the Highland tenantry, who anticipated with delight the time, which never

came, when he might be their landlord in very deed.” “The glories,” says Mrs

Gordon, “of the Grampian scenery contributed more than anything to the

enjoyment of his residence in Badenoch. The beauties of the Doune, Kinrara,

and Aviemore, Loch-an-Eilan, Loch Insh, Loch Laggan, Craigdhu, the Forest of

Gaick, and the magnificent desolation of Glen Feshie, were all vividly

enjoyed by him with that inner sense of poetry and art which he so

pre-eminently possessed. His old friend, John Thomson, the minister of

Duddingston, but better known as a master in Scottish landscape, came to

visit him, and was of course taken to see Glen Feshie, with its wild corries

and moors, and the giants of the old pine-forest. After a deep silence, my

father was startled by the exclamation, ‘Lord God Almighty!’and on looking

round he saw the strong man bowed down in a flood of tears, so much had the

wild grandeur of the scene and the sense of the One creative hand possessed

the soul of the artist. Glen Feshie afterwards formed the subject of one of

Thomson’s best pictures.”

Mrs Gordon relates that on one occasion four working-men came to Sir David,

a considerable distance from Strathspey, with the petition that they might

see the stars through his telescope. On another occasion a poor man brought

his cow a weary long journey over the hills that the great optician might

examine her eyes and prescribe for her deficiencies of sight; and all, as

was ever his wont, were received courteously, and had their questions not

only answered, but answered so clearly and patiently that the subjects were

made perfectly intelligible and interesting. The well-known Edward Ellice,

M.P., was then at Invereshie, and at the Doune of Rothiemurchus the late

Duchess of Bedford, a daughter of the famous Jane, Duchess of Gordon, with

her gay circle of fashion, of statesmen, artists, and lions of all kinds,

produced a constant social stir in which Sir David was frequently called to

bear his part, and he retained many lively recollections and anecdotes of

the strange scenes and practical jokes of that “fast circle. Upon one

occasion he and Lord Brougham, when Lord Chancellor, were visiting at the

Doune: Lord Brougham, being indisposed, retired early to rest one evening.

An hour or two afterwards the question was raised, Whether Lord Chancellors

carried the Great Seal with them in social visiting? The Duchess declared

her intention of ascertaining the fact, and ordered a cake of soft dough to

be made. A procession of lords, ladies, and gentlemen was then formed, Sir

David carrying a pair of silver candlesticks, and the Duchess bearing a

silver salver on which was placed the dough. The invalid Lord was roused

from his first sleep by this strange procession, and a peremptory demand

that he should get up and exhibit the Great Seal. He whispered ruefully to

Sir David that the first half of this request he could not possibly comply

with, but asked him to bring a certain strange-looking box : when this was

done, he gravely sat up, impressed the seal upon the cake of dough, the

procession retired in order, and the Lord Chancellor returned to his pillow.

Sir David, we are likewise told, “was much interested in all the old tales

and legends of the country, and took much pains in excavating a strange

hollow, of which many clannish stories were told, but which turned out to be

a Piet’s house. The parallel roads of Glenroy, long believed to be the

hunting-roads of the old kings of Scotland, with the various geological

solutions of the ancient mystery, were objects of vivid interest. The weird

stories of the glen and forest of Gaick, and the traditions of ‘Old Borlum,’

a Highland laird with certain Robin Hood views as to the rights of meum and

tuum, who had formerly possessed Belleville, were repeated by him with

lively interest; the cave from which Borlum and his men used to watch for

travellers on the old Highland road was always pointed out to visitors; and

he used to relate, as an example of the primitive state of society in the

north which would

scarcely be credited in the south, that he had himself been in society,

during his earlier Badenoch life, with Mrs Mackintosh of Borlum, the

brigand’s widow, a stately and witty old lady. One day she had called at

Belleville, and took up ‘Lochandhu,’ a novel just published by Sir Thomas

Dick Lauder. ‘ Ay, ay,’ said she, ‘and what may this be about?’ to the

consternation of the Belleville ladies—her husband’s capture and robbery of

Sir Hector Munro of Novar, and her own assistance in this, his last exploit,

by picking out the initials on the stolen linen, being graphically detailed

therein!"

Although, strictly speaking, not situated in Badenoch, it would be

unpardonable to omit reference to the celebrated Loch-an-eilan (the Loch of

the Island) on the other side of the Spey, within a short distance of

Kinrara, and one of the most beautiful resorts in the Highlands.

“A fir lake,” says Macculloch, “if I may use such a term, is a rare

occurrence; and indeed this is the only very perfect example in the country.

No other tree is seen; yet, from the variety of the shores, there is not

that monotony which might be expected from such limited materials. In some

parts of it, the rocky precipices rise immediately from the deep water,

crowned with the dark woods, that fling a profound shadow over it; in

others, the solid masses of the trees advance to its edge; while elsewhere,

open green shores, or low rocky points, or gravelly beaches, are seen,—the

scattered groups, or single trees, which, springing from some bank, wash

their roots in the waves that curl against them, adding to the general

variety of this wild and singular scene. This lake is much embellished by an

ancient castle, standing on an island within it, and, even yet, entire

though roofless. As a Highland castle, it is of considerable dimensions; and

the island being scarcely larger than its foundation, it appears in some

places to rise immediately out of the water. Its ancient celebrity is

considerable, since it was one of the strongholds of the Cumins, the

particular individual whose name is attached to it being the ferocious

personage known by the name of the Wolf of Badenoch. It has passed now to a

tenant not more ferocious, who is an apt emblem and representative of the

red-handed Highland chief. The eagle has built his eyrie on the walls. I

counted the sticks of his nest, but had too much respect for this worthy

successor to an ancient Highland dynasty even to displace one twig. His

progeny, it must be admitted, have but a hard bed ; but the Red Cumin did

not probably lie much more at his ease. It would not be easy to imagine a

wilder position than this for a den of thieves and robbers, nor one more

thoroughly romantic: it is more like the things of which we read in the

novels of the Otranto school, than like a scene of real life. If ever you

should propose to rival the author of ‘Waverley’1 in that line of art, I

recommend you to choose part of your scene here. As I lay on its topmost

tower amid the universal silence, while the bright sun exhaled the perfume

from the woods around, and all the old world visions and romances seemed to

flit about its grey and solitary ruins, I too felt as if I could have

written a chapter that might hereafter be worthy of the protection of

Minerva.”

On the verge of the lake nearest the castle any high-pitched cry or loud

halloo awakens a remarkable echo, the reverberations of which up the

mountain-side have a very weird and striking effect.

“The lands of Rothiemurchus,” says Shaw, “having been granted by King

Alexander II. to Andrew, Bishop of Moray, anno 1226, were held of the

Bishops in lease by the Shaws, during a hundred years without disturbance.

But about the year 1350, Cummine of Strathdallas having a lease of these

lands, and unwilling to yield to the Shaws, it came to be decided by the

sword, and (1) James Shaw, chief of the clan, was killed in the conflict.

James had married a daughter of Baron Ferguson, in Athole; and his son (2)

Shaw, called Corfiachlach, as soon as he came of age, with a body of men

attacked Cummine, and killed him, at a place called to this day

Lagna-Cumimch. He purchased the freehold of Rothiemurchus and Balinespic,

and by a daughter of Macpherson of Clunie had seven sons, James the eldest,

and Farquhar, ancestor of the Farquharsons, &c. Shaw commanded the XXX. Clan

Chattan on the Inch of Perth, anno 1396, and dying about 1405, his

gravestone is seen in the churchyard. (3) James brought a company of his

name to the battle of Hardlaw, anno 1411, where he was killed. His son, by a

daughter of Inveretie, (4) Alexander Kiar, by a daughter of Stuart of

Kinchardine, had four sons, of whom Dale, Tordarroch, and Delnafert are

descended; and (5) John, by a niece of Macintosh, was father of (6) Allan,

who, by a daughter of the Laird of Macintosh, had (7) John, father of (8)

Allan, who, having barbarously murdered his stepfather, Dallas of Cantray,

was justly forfeited, and the Laird of Grant purchased the forfeiture about

anno 1595.”

In leaving the portion of Badenoch situated in the parish of Alvie, the

beautiful lines of the Rev. Dr Wallace in his “Farewell to Strathspey” may

be appropriately quoted :—.

“Oh the bonny blooming

heather! what nameless charms it hath,

As it spreads for miles around on my lonely mountain path.

The hills and dells, and knowes and glades, are clad in purple sheen,

And far away beneath the pines what a sea of glossy green!

Soft carpet for the weary feet, sweet solace to the brain,—

Here rest a while and listen to nature’s soothing strain.

A holy calm now breathes around in the murmur of the trees,

And wakes the music of the heart in every passing breeze.” |