|

IN the ‘New Statistical

Account’ of the parish of Kingussie, published in 1842, it is related that

the whole district of Badenoch, of which Kingussie is the central parish (or

capital), was originally the property of the Comyns, who were at an early

period of Scottish history one of the most wealthy and influential families

in the kingdom. It is matter of doubt at what time and in what manner this

family, who came from England during the time of David I., acquired

possession of it, but we find John Comyn first noticed as Lord of Badenoch

as early as the reign of Alexander III. This, nobleman, who was related to

some of the former kings, laid claim to the crown upon the death of Margaret

in 1291, but soon after withdrew his pretensions. Being the superior Lord of

Scotland, he was summoned by Edward I. to serve in his wars in Gascony. He

was succeeded in his title and estates by his son John, a brave and

patriotic nobleman, who was chosen one of the Guardians of Scotland about

the year 1299. From this period down to the year 1305 we meet with

incidental notices of this heroic character in his relation to Badenoch, but

the principal scenes of his life lay in the south. In 1302, with the

assistance of another warrior, he successfully repelled the English forces

near Roslin. Two years thereafter he made a last fruitless struggle for

Scottish independence at Stirling, but was obliged to yield along with his

country to the overwhelming power of Edward I. In the succeeding year he

fell a victim to the relentless fury of Bruce, afterwards king, for having

discovered to Edward the designs of the former upon the crown of Scotland.

For about nine years after Comyn’s death, we find no mention of a successor

to his lands or title. According to Fordun, soon after Bruce ascended the

throne in 1306 he so weakened the influence and reduced the numbers of the

family of Comyn, that the name became almost extinct in the kingdom. In all

probability Badenoch, upon the murder of its original owner, was taken

possession of by Bruce, as we find it noticed among the lands belonging to

him in Moray, which he erected into an earldom about the year 1314, and

bestowed upon his nephew, Thomas Randolph, under the title of Earl of Moray.

In the hands of this nobleman and his successors it seems to have continued

till the year 1371 or thereabouts, when it became the property of the family

of Stewart, which was nearly allied to that of Bruce. Robert II., the

grandson of Robert Bruce, and the first of the Stewarts who ascended the

Scottish throne, constituted his fourth son, Alexander, his lieutenant from

the southern boundaries of Moray to the Pentland Firth, in whom the title of

Lord of Badenoch appears to have been first revived after Comyn’s death. The

ferocity of disposition and predatory character of Alexander soon gained for

him the appellation of the Wolf of Badenoch. He resided for the most part at

his castle of Ruthven, reared by the Comyns on a green conical mound on the

southern bank of the Spey, about half a mile from Kingussie—a situation

chosen, no doubt, on account of its beauty and security, as well as for the

extensive and delightful view which it commanded of the valley of the Spey.

Here the Wolf, considering himself secure, and presuming upon his connection

with the Crown, exercised a despotic sway over the inhabitants of his own

immediate district, and spread terror and devastation everywhere around. His

life was characterised throughout by the most cruel and savage conduct. It

was he who in 1390 and the following year, from some personal resentment

against the Bishop of Moray, set fire to the towns of Forres and Elgin,

which, with the magnificent cathedral, canons houses, and several other

buildings connected with the latter, he burnt to ashes, carrying off at the

same time all that was valuable in the sacred edifice. For this sacrilegious

deed the Wolf suffered excommunication, the effects of which he soon felt

even in his den; and having made what reparation he could to the See of

Moray, he was subsequently absolved. The Wolf died not long after, in 1394,

and was buried in the Cathedral Church of Dunkeld, where the following Latin

inscription was placed upon his tomb :—

“Hie jacet Alexander Seuescallus filius Roberti regis Scotorum et

Elizabethan More Dominus de Buchan et Badenoch qui obiit a.d. 1394.”

By the death of a last air Mor Mac an Righ—a name sometimes applied to the

Wolf—his possessions fell to his natural son, Duncan, who seems to have

inherited the vices as well as the property of his father. Duncan was the

last of the Stewarts connected with Badenoch of whom there is any account,

written or traditional. The district some time after this period passed into

the hands of the first Earl of Huntly, who received part of it in 1452 for

his valuable services to James II. in defeating the Earl of Crawford at

Brechin. The lands adjacent to the Castle of Ruthven were given to him at an

earlier period, and the principal part of the lordship continued in the

hands of the Gordon family until the third decade of the present century.

So early as 1597 a deputation was appointed by the General Assembly to visit

the northern Highlands, and in a report subsequently presented by the

deputation to the Assembly, James Melvin (one of their number) states as the

results of his own observations in the wild and then almost inaccessible

district of Badenoch: “Indeid, I have ever sensyne regrated the esteat of

our Hielands, and am sure gif Chryst war pretched amang them they wald scham

monie Lawland professours ”—a prediction which, if any fearless, independent

member of the “Highland Host” would venture, after the manner of the old

Covenanting, trumpet-tongued lady friend of Norman Macleod, simply to ask

certain “Lawland” Principals as well as “Professours” to gang ower the

fundamentals, might probably be held to be verified even in the present day.

In 1229 or thereabouts Badenoch “appears as Badenach in the Registrum of

Moray Diocese, and this is its usual form there; in 1289, Badenagh,

Badenoughe, and in King Edward’s Journal, Badnasshe; in 1366 we have

Baydenach, which is the first indication of the length of the vowel in Bad-;

a fourteenth-century map gives Baunagd; in 1467, Badyenach; in 1539,

Baidyenoch; in 1603 (Huntly rental), Badzenoche; and now in Gaelic it is

Baideanach. The favourite derivation, first given by Lachlan Shaw, the

historian of Moray (1775), refers it to badan, a bush or thicket; and the

Muses have sanctioned it in Calum Dubh’s expressive line in his poem on the

Loss of Gaick (1800)—

‘’S bidh muirn ann an Duthaich nam Badan.’

(And joy shall be in the Land of Wood-clumps.)

But there are two fatal objections to this derivation: the a of Badenoch is

long, and that of badan is short; the d of Badenoch is vowel-flanked by

‘small’ vowels, while that of badan is flanked by ‘broad’ vowels and is

hard, the one being pronounced approximately for English, as bah-janach, and

the other as baddanach. The root that suggests itself as contained in the

word is that of bath or badh (drown, submerge), which, with an adjectival

termination in de, would give bdide, ‘submerged, marshy,’ and this might

pass into bdidean and baideanach, ‘marsh or lake land.’ That this meaning

suits the long, central meadow-land of Badenoch, which once could have been

nothing else than a long morass, is evident. There are several places in

Ireland containing the root badh (drown), as Joyce points out. For instance,

Bauttagh, west of Loughrea in Galway, a marshy place; Mullanbattog, near

Monaghan, hill summit of the morass; the river Bauteoge, in Queen’s County,

flowing through swampy ground; and Currawatia, in Galway, means the

inundated curragh or morass. The neighbouring district of Lochaber is called

by Adamnan Stagnum Aporicum, and the latter term is likely the Irish abar (a

marsh), rather than the Pictish aber (a confluence); so that both districts

may be looked upon as named from their marshes.”

Ceann-a ghuibhsaich, the Celtic name for Kingussie, appears to have been

adopted as the name of the parish from its being so descriptive of the site

of the parish church. It signifies the termination or head of the fir-wood.

When the name was given the church stood upon a plain at the eastern

extremity of a clump of wood, forming part of an immense forest of fir which

then covered the face of the country. Including hill and dale, the parish

extends from north to south a distance of nearly twenty miles, and from east

to west about fifteen. The area is 181 square miles, or 116,182 acres. The

parish of Kingussie is situated in the lordship of Badenoch, and ranks among

the most elevated and most inland parishes in Scotland. The bed of the Spey

at Kingussie is about 740 feet above the level of the sea. The Spey, which

is said to be the Tuessis of Ptolemy, rises at Corryarrick, within

twenty-six miles from Kingussie, is the most rapid river in Scotland, has a

total run of nearly 100 miles, and drains about 1300 square miles of

country. “For three centuries,” says Skene, “it formed the boundary between

Scotia, or Scotland proper, and Moravia, or the great province of Moray.”

From the large extent and high-lying character of its sources, as well as of

its principal tributaries, it is subject to very sudden and heavy floods.

The greatest flood on record is the memorable one of August 1829, (which Sir

Thomas Dick Lauder gives such a graphic description in his ‘Account

of the Moray Floods,’ published at Edinburgh in 1830. “The Spey and its

tributaries above Kingussie,” says Sir Thomas, “were but little affected by

the flood of the 3d and 4th of August. The western boundary of the fall of

rain seems to have been about the line of the river Calder, which enters the

Spey from the left bank, a little to the westward of the village. The deluge

was tremendous, accompanied by a violent north-east wind, and frequent

flashes of lightning, without thunder. . . . About Belleville, and on the

Invereshie estate, the meadows were covered to the extent of five miles long

by one mile broad. . . . The river Feshie, a tributary from the right bank,

immediately below Invereshie, was subjected to the full influence of the

deluge. It swept vast stones and heavy trees along with it, roaring

tremendously. . . .

John Grant, the saw-miller’s house, at Feshieside, was surrounded by four

feet of water, about eight o’clock in the morning of the 4th. The people on

the top of a neighbouring hill fortunately observed the critical situation

of the family; and some men, in defiance of the tremendous rush of the

water, then 200 yards in breadth, gallantly entered, as Highlanders are wont

to do in trying circumstances, shoulder to shoulder, and rescued the inmates

of the house, one by one, from a peril proved to be sufficiently imminent by

the sudden disappearance of a large portion of the saw-mill. But, great as

was the danger in this case, the lonely and deserted situation of Donald

Macpherson, shepherd in Glenfeshie, with his wife and six little children,

was still more frightful, and required all the firmness and resolute

presence of mind characterising the hardy mountaineer. His house stood on an

eminence, at a considerable distance from the river. Believing, therefore,

that whatever might come, he and his would be in perfect safety, he retired

with his family to bed at the usual hour on the evening of the 3d. At

midnight he was roused by the more than ordinary thunder of the river, and

getting up to see the cause, he plunged up to the middle in water. Not a

moment was to be lost. He sprang into his little dwelling, lifted, one after

the other, his children from their beds, and carried them, almost naked,

half asleep, and but half conscious of their danger, to the top of a hill.

There, amidst the wild contention of the elements, and the utter darkness of

the night, the family remained shivering and in suspense, till daybreak,

partially illuminating the wildness of the scenery of the narrow glen around

them, informed them that the flood had made them prisoners in the spot where

they were, the Feshie filling the whole space below, and cataracts falling

from the rocks on all sides. Nor did they escape from their cliff of penance

till the evening of the following day. The crops in Glenfeshie were

annihilated. The romantic old bridge at Invereshie is of two arches of 34

and 12 feet span. The larger of these is 22 feet above the river in its

ordinary state, yet the flood was 3 feet above the keystone, which would

make its height here above the ordinary level about 25 feet. The force

pressing on this bridge must have been immense; and, if we had not already

contemplated the case of the Ferness Bridge, we should consider the escape

of that of Feshie to be a miracle. Masses of the micaceous rock below the

bridge, of several tons’ weight, were rent away, carried down, and buried

under heaps of gravel at the lower end of the pool, 50 or 60 yards from the

spot whence they were taken. The Feshie carried off a strong stone bulwark a

little farther down, overflowed and destroyed the whole low ground of

Dalnavert, excavated a new channel for itself, and left an island between it

and the Spey of at least 200 acres. The loss of crop and stock by the

farmers hereabouts is quite enormous, and the ruin to the land very great.”

Sir Thomas relates a very whimsical result at the farm of Dalraddy, in

consequence of the flooding of the burn of that name which flows into Loch

Alvie: “The tenant’s wife, Mrs Cumming, on going out after the flood had

subsided on Tuesday afternoon, found, at the back of the house, and all

lying in a heap, a handsome dish of trout, a pike, a hare, a partridge, and

a turkey, with a dish of potatoes and a dish of turnips— all brought down by

the burn, and deposited there for the good of the house, except the turkey,

which, alas! was one of her own favourite flock. The poor hare had been

surprised on a piece of ground insulated by the flood, and had been seen

alive the previous evening, exhibiting signs of consternation and alarm; and

the stream rising yet higher during the night, swept over the spot, and

consummated its destruction.” The parish of Kingussie is bounded on the east

by Alvie, on the north by the united parishes of Moy and Dalarossie, on the

west by Laggan, and on the south by Blair in Athole. Within the parish the

Monadhliath—i.e., the grey mountains—stretch along the boundary for a

considerable way, serving as a northern frontier; while the Grampians,

rising in bold perspective in the distance, bound the parish on the south.

In an old Gaelic rhyme the heights in the Monadhliath range between

Kingussie and Craig Dhu are thus described :—

“Creag-bheag Chinn-a’-ghuibhsaich,

Creag-mhoir Bhail’-a’-chrothain,

Beinne-Bhuidhe na Sroine,

Creag-an-loin aig na croitean,

Sithean-mor Dhail-a’-Chaoruinn,

Creag-an-abhaig a’ Bhail’ shios,

Creag-liath a’ Bhail’ shuas,

’S Creag-Dhubh Bhiallaid,

Cadha’-n fheidh Lochain-ubhaidh,

Cadh’ is mollaicht ’tha ann,

Cha’n fhas fikr no fodar ann,

Ach sochagan is dearcagan-allt,

Gabhar air aodainn,

Is laosboc air a’ cheann.”

In the south range of the Monadhliath hills, in sight of Kingussie, is Cam

an Fhreiceadain—i.e., the Watch Hill or Cairn—so called from the fact of its

being occupied for a time by a detachment of Am Freiceadan Dubh, or Black

Watch. After that famous regiment was raised in the early part of last

century, detachments of the regiment acted in various parts of the Highlands

as a sort of native police for the suppression of cattle-lifting—a practice

very common in bygone times on the part of some freebooters, whose views as

to the rights of meum and tuum were of such a kind as to regard it a shame

to want anything that could be had for the taking—

“Because the good old rule

Sufficed them, the simple plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.”

From its geographical position Cam an Fhreiceadain was chosen as one of the

principal stations of the Black Watch for the purpose of checking the

depredations of the rievers on their way through Badenoch to Lochaber.

Although of less conspicuous altitude than its neighbours of the Grampian

range, and left unnoticed by guide-writers, there is no summit in the

Highlands so easy of access from which a more extensive view can be obtained

than from the hill-top chosen by the old Black Watch as the eyrie from which

to observe the movements of the rievers.

From the top of Cam an Fhreiceadain, on a clear day, all the mountain-tops

of the north of Scotland, from Ben Nevis in the west, round by Skye and

Sutherland to the Ord of Caithness in the far north-east, are visible to the

naked eye. No matter whether the cattle-raiders were returning with their

booty from Aberdeen, Banff, or Moray shires in the one direction, or from

Easter Ross in the other, the sentinel on Cam an Fhreiceadain was apprised,

either by smoke in the day or the beacon-fire during the night, of the

approach of the rievers, and able to give the alarm—leading to measures

being immediately adopted in the way of pouncing down upon the unsuspecting

raiders and relieving them of their prey, to be restored to the rightful

owners.

A picturesque glimpse of the Highland marauding of olden times was obtained

many years ago at second-hand, from the memory of William Ban Macpherson,

who died in 1777 at the age of a hundred :—

“He was wont to relate that, when a boy of twelve years of age, being

engaged as buachaille (herd-boy) at the summering (i.e., summer grazing) of

Biallid, near Dalwhinnie, he had an opportunity of being an eyewitness to a

creagh and pursuit on a very large scale, which passed through Badenoch. At

noon on a fine autumnal day in 1689, his attention was drawn to a herd of

black cattle, amounting to about six score, driven along by a dozen of wild

Lochaber men, by the banks of Loch Erricht, in the direction of Dalunchart,

in the forest of Alder, now Ardverikie. Upon inquiry, he ascertained that

these had been ‘lifted’ in Aberdeenshire, distant more than a hundred miles,

and that the rievers had proceeded thus far with their booty free from

molestation and pursuit. Thus they held on their way among the wild hills of

this mountainous district, far from the haunts of the semi-civilised

inhabitants, and within a day’s journey of their home. Only a few hours had

elapsed after the departure of these marauders, when a body of nearly fifty

horsemen appeared, toiling amidst the rocks and marshes of this barbarous

region, where not even a footpath helped to mark the intercourse of society,

and following on the trail of the men and cattle which had preceded them.

The troop was well mounted and armed, and led by a person of gentlemanlike

appearance and courteous manners while attached to the party was a number of

horses carrying bags of meal and other provisions, intended not solely for

their own support, but, as would seem from the sequel, as a ransom for the

creagh. Signalling William Ban to approach, the leader minutely questioned

him about the movements of the Lochaber men, their number, equipments, and

the line of their route. Along the precipitous banks of Loch Erricht this

large body of horsemen wended their way, accompanied by William Ban, who was

anxious to see the result of the meeting. It bespoke spirit and resolution

in those strangers to seek an encounter with the robbers in their native

wilds, and on the borders of that country, where a signal of alarm would

have raised a numerous body of hardy Lochaber men ready to defend the creagh

and punish the pursuers. Towards nightfall they drew near the encampment of

the thieves at Dalunchart, and observed them busily engaged in roasting,

before a large fire, one of the beeves, newly slaughtered. A council of war

was immediately held, and on the suggestion of the leader, a flag of truce

was forwarded to the Lochaber men, with an offer to each of a bag of meal

and a pair of shoes in ransom for the herd of cattle. This offer, being

viewed as a proof of cowardice and fear, was contemptuously rejected, and a

reply sent to the effect that the cattle, driven so far and with so much

trouble, would not be surrendered. Having gathered in the herd, both parties

prepared for action. The overwhelming number of the pursuers soon mastered

their opponents. Successive discharges of firearms brought the greater

number of the Lochaber men to the ground, and in a brief period only three

remained unhurt, and escaped to tell the sad tale to their countrymen.”

But even these cattle-lifters were not without some redeeming qualities, as

illustrated in the case of one of the most noted of their number. John Dhu

Cameron, from his large size called Sergeant Mor, having been out in the

’45, formed a party of freebooters, and levied black-mail among the

mountains between Perth and Inverness. On one occasion he met an officer of

the garrison of Fort William, who told him that he suspected he had lost his

way; and having a large sum of money for the garrison, he was afraid of

meeting the Sergeant Mor. He therefore requested the stranger to accompany

him on the road. The other agreed; and while they walked on they talked much

of the sergeant and his feats, the officer using much freedom with his name,

calling him robber and murderer. “Stop there,” interrupted his companion;

“he does, indeed, take the cattle of the Whigs and of you Sassenachs, but

neither he nor his cearnachs ever shed innocent blood—except once,” added

he, “that I was unfortunate at Braemar, when a man was killed; but I

immediately ordered the creach [the spoil] to be abandoned, and left to the

owners.” “You!” says the officer; “what had you to do with the affair?” “I

am John Dhu Cameron—I am the Sergeant Mor! There is the road to Inverlochy—you

cannot now mistake it. You and your money are safe, but tell your governor

to send a more wary messenger for his gold. Tell him, also, that although an

outlaw, and forced to live on the public, I am a soldier as well as himself,

and would despise taking his gold from a defenceless man who confided in

me!” The officer lost no time in reaching the garrison, and never forgot

this adventure, which he frequently related.

“Let us,” says the late Dr Carruthers of Inverness in his delightful

‘Highland Note-Book,’ written about half a century ago—“let us place

ourselves in the heart of the Glengarry country, or the wild Monadhliath

mountains in Inverness-shire. First you have, directly above the black

foaming stream, or the glen of soft green herbage, a ridge of brown heathery

heights, not very imposing in form or altitude; then a loftier range, with a

blue aspect; a third, scarred with snow, and serrated perhaps, or peaked at

their summits; then a multitudinous mass, stretching away in the distance,

of cones, pyramids, or domes, darkly blue or ruddy with sunshine, the

shadows chasing one another across their huge limbs, revealing now and then

the tail of a cataract, a lake, or the relics of a pine-forest once mighty

in its gloomy expanse of shade in the olden time; a panorama of mountains,

as if instinct with life and motion! To call such a scene dull or uniform,

such a vast assemblage of titanic forms, warring with the elements or

reflecting their splendour, as unlovely or unattractive, is a sacrilege and

desecration of the noblest objects in creation. Dear are the homes, and warm

the hearts, hid among these wild fastnesses! You look, and at the foot of a

crag on the moorland, from which it can scarcely be distinguished, you

discern a hut. Its walls are of black turf; window or chimney it has none

save rude apertures; yet pervious to all the blasts that blow, like

hurricanes, in the trough of these mountain-ranges, the hut stands, and the

peasants live and bring forth in safety. You enter, and find the

grandmother, bent double with age, or the grey-haired sire, the only inmate

of the house. The husband has gone to dig turf, or to perform some other

out-of-doors occupation; the children are over the hill, barefoot, to

school; and the wife or daughter is at the shealing, a fertile valley among

the mountains where all the neighbours take their cattle in summer to graze.

Poor is the hut in which the stranger is not offered some refreshment, and

is greeted, in few words of broken English, with a cordial welcome. In

cottages like these, amidst the veriest gloom and poverty, still subsist a

high-souled generosity, stainless faith, and feudal politeness, spontaneous

and unbought; and from these huts have sprung brave and chivalrous men, who

have carried their country’s renown into many a foreign land. The vices of

the poor Highlander are, in reality, the vices of his chief or landlord. He

is wholly dependent on the latter, and his devotion to him is unquenched and

unquenchable. The mould of his character, his feelings, and fortunes are in

his chief’s hand. Some hundreds of young vigorous Highlanders have this

season emigrated to Australia—a pastoral country suited to their habits and

inclinations—but never without the most poignant regret and distress. The

pibroch is played at their departure, and the old Gaelic chant of the

exiles, ‘Cha till sinn tuilidh’ —‘We return no more’—sounds as melancholy

now among the deserted glens as it ever did at the period of the great

emigration to America at the close of the last century.”

A curious old tradition has it that a native of Stratherrick, favoured with

the supernatural gift of conveying the milk of his neighbour’s cattle to his

own, came over to Badenoch with the view of practising his art in favour of

his own country generally. He succeeded so far as to be able to confine the

Badenoch milk in a withe which he carried across the Monadhliath range to

the height of Killin (a dell at the top of Stratherrick), where, in virtue

it is supposed of a counter-spell by the bereaved country, it burst and

overflowed that delightful plain. This, so the tradition runs, has been the

cause of the richness of the pasture of that plain, and of the superior

quality and quantity of milk it produces. The good effects of this untoward

accident were not, it is related, confined to the dell of Killin, for some

of its streamlets glided down to Stratherrick, which is said to account for

the excellence of the milk, cream, and butter in that district.

Within a mile or two from Kingussie, on the other side of the Spey, there

lived last century the famous witch of Laggan, of whom the following account

is given :—

Scotch Highlanders have faults in plenty; but they have the bearing of

Nature’s own gentlemen—the delicate natural tact which discovers, and the

good taste which avoids, all that would hurt or offend a guest. The poorest

is ever the readiest to share the best he has with the stranger. A kind word

kindly meant is never thrown away; and whatever may be the faults of this

people, I have never found a boor or a churl in a Highland bothy.”

“It happened that a hero distinguished for hatred and persecution of

witchcraft was abroad hunting deer in the wild forest of Gaick in Badenoch.

There the storm raged with exceeding violence, and the hunter of the hills

had retired to his bothy for shelter from the storm ; his gun reclined in a

corner, his skean-dhu hung by his side, and his two faithful hounds lay

stretched at his feet, all listening to the whistling of the raging storm,

when a miserable-looking, weather-beaten cat entered the bothy. The hounds

immediately raised themselves from the ground, their hairs became erected

bristles, and they essayed an attack upon the cat, when the cat offered a

parley, entreating the hunter to restrain the fury of his dogs, and claiming

the protection of the hunter as being a poor unfortunate witch who had

recanted her errors, had consequently experienced the harshest treatment of

the sisterhood, and had fled, as the last resource, to the hunter for

protection. Believing her story to be true, and disdaining at any rate to

take advantage of his greatest enemy in her present forlorn situation, the

hunter, with some difficulty, pacified his infuriated dogs, and invited the

cat to come towards the fire and warm herself. ‘Nay,’ says the cat, ‘if I

do, those furious hounds of yours will tear my poor hams to pieces; I pray

you, therefore, take this long hair and tie the dogs therewith to that beam

of the house, that I may be secure from their molestation.’ The hunter took

the hair, and taking the dogs aside, he pretended to bind them as he was

directed; but instead of which, he only bound it round the beam, or what is

called the couple, which supported the roof of the bothy; and the cat,

supposing that her injunctions had been complied with, advanced to the fire,

and squatted herself down as if to warm herself, but she speedily began to

expand her size into considerable dimensions; on which the hunter jocularly

remarked to her,

‘An evil death to you, nasty beast: you are getting very large.’ ‘Ay, ay,’

says the cat, equally jocosely, ‘as my hairs imbibe the heat, they naturally

expand.’ But still her dimensions gradually increased until about the size

of a large hound, when, in a twinkling, she assumed the similitude of a

woman; and to the horror and amazement of the hunter, she presented to him

the appearance of a neighbour whom he had long known under the name and

title of ‘ The good wife of Laggan,’ a woman whom he had previously supposed

to be a paragon of virtue. ‘ Hunter of the hills,’ exclaimed the wife of

Laggan, ‘ your hour is come; the day of reckoning is arrived. Long have you

been the devoted enemy of my persecuted sisterhood. The chief aggressor

against our order is now no more,—this morning I saw his body consigned to a

watery grave; and now, hunter of the hills, it is your turn.’ Whereupon she

flew at his throat with the force and fury of a tigress ; and the dogs, whom

she supposed securely bound by the hair, flew at her breast and throat in

return. Being thus unexpectedly attacked, she cried out, addressing herself

to the hair, ‘Fasten, hair; fasten!’ and so effectually did the hair obey

the order, that it snapped the piece of wood on which it was tied in twain.

Finding herself thus deceived, the good wife of Laggan attempted a flight,

but the dogs clung to her breasts so tenaciously that they only parted with

their hold on the demolition of all the teeth in their heads; and one of

them succeeded in tearing off the greater part of one of her breasts before

she could get him disengaged from her person. At length, with the most

fearful shrieks, she assumed the likeness of a raven, and flew in the

direction of her home. The two dogs, his faithful defenders, were only able

to return to lick the hands of their master, and to expire at his feet.

Regretting their loss with a sorrow which is only known to a father who

loses his favourite children, he remained to bury his dogs, and then

proceeded to his home full of those astounding and melancholy reflections

which the scene he had been engaged in was so much calculated to produce. On

his arrival at home, his wife was absent; but after an interval she made her

appearance, and in the course of providing for his entertainment, she told

him, under feelings of great concern, that she had been visiting the good

wife of Laggan, who having been all day sorting peats in the moss, had got

wet feet and a severe colic, and all her neighbours were just awaiting her

demise. Her husband remarked, ‘ Ay, ay; it is proper that I also should go

and see her,’ on which he repaired to her bedside, and found all the

neighbours wailing over the expected decease of a highly esteemed friend and

neighbour. The hunter, under the excited feelings natural to the

circumstances of the case, instantly stript the wife of her coverings, and

calling the company around her, ‘Behold,’ says he, ‘the object of your

solicitude. This morning she was a party to the death of the renowned John

Garve M'Gillechallum of Razay, and to-day she attempted to make me share his

doom; but the arm of Providence has overtaken the servant of Satan in her

career, and she is now about to expiate her crimes by death in this world,

and punishment in the next.’ All were seized with consternation; but the

marks upon her person bore conclusive proofs of the truth of the tale of the

hunter, and the good wife of Laggan did not even attempt to disguise the

veracity of his statement, but addressing herself to her auditors in the

language of penitent confession, she said: ‘My dear and respected friends,

spare, oh spare an old neighbour while in the agonies of death from greater

mortal degradation. Already the enemy of your souls and of mine, who seduced

me from the walks of virtue and happiness, as a reward for my anxious and

unceasing labours in his service, only waits to lead my soul into eternal

punishment! And, as a warning to all others to shun the awful rock on which

I have split, I shall detail to you the means and artifices by which I was

led into the service of the evil one, and the treachery which I and all

others have experienced at his hands.’ Here the good wife of Laggan narrated

the particulars of the means by which she had been seduced into the service

of Satan, the various adventures in which she had been engaged, concluding

with the death of Razay, and the attack on the hunter; and in the midst of

the most agonising shrieks she, in the presence of all assembled, gave up

the ghost. On the same night two travellers were journeying from Strathdearn

to Badenoch, across the dreary hill of Monadhliath. While about the centre

of the hill, they met the figure of a woman, with her bosom and front

besmeared with blood, running with exceeding velocity along the road in the

direction of Strathdearn, uttering at intervals the most loud and appalling

shrieks, to which the hills and rocks responded in echo. They had not

proceeded far when they met two black dogs, as if on the scent of the track

of the woman; and they had not proceeded much farther when they met a black

man upon a black horse, coursing along in the direction of the woman and the

dogs. ‘Pray,’ says the rider, ‘did you meet a woman as you came along the

hill?’ The travellers answered in the affirmative. ‘And,’ continued the

rider, ‘did you meet two dogs following the tracks of the woman?’ The

travellers having answered in the affirmative, the rider added, ‘Do you

think the dogs would have caught her before she could have reached the

churchyard of Dalarossie?’ The travellers answered, ‘They would at any rate

be very close upon her heels.’ The parties then separated, the horseman

proceeding with the greatest fleetness after the woman and the dogs. The

travellers had not emerged from the forest of Monadhliath when they were

overtaken by the black rider, having the woman across the bow of his saddle,

with one dog fixed in her breast, and the other in her thigh. ‘Where did you

overtake the woman?’ said one of the travellers to the rider, to which he

answered, ‘Just as she was about to enter the churchyard of Dalarossie.’ On

arriving at home the travellers heard of the melancholy fate of the good

wife of Laggan ; and there existed no doubt on the minds of all to whom the

facts were known that it was the spirit of the wife of Laggan who was

running to the churchyard of Dalarossie, which was esteemed and known to be

sacred ground, and a pilgrimage to which, either dead or alive, released the

subjects of Satan from their bonds to him. But unfortunately for the poor

wife of Laggan, she was a stage too late.”

As the capital of the old

lordship of Badenoch, Kingussie has been well known in Highland history for

many centuries, and the district generally abounds in points of historical

interest, some of which are noticed in other portions of this volume. “Not a

turn of the river,” says Dr Longmuir in his ‘Speyside,’ an interesting

little work published in Aberdeen in 1860, now out of print, “not a pass in

the mountains, or the name of an estate, that does not recall some wild

legend of the olden, or some thrilling event of more recent times; not a

plain that is not associated with some battle; not a castle that has not

stood its siege or been enveloped in flames ; not a dark pool or gloomy loch

that has not its tale either of guilt or superstition; not a manse that has

not been inhabited by some minister that eminently served his Master. . . .

Or, turning from the castle to the cairn, from the kirk to the cromlech,

what a field is opened up to the investigator of the manners of the past!

The inhabitants of these straths drawing around the cruel rites of the

Druidical circle where human sacrifices were offered up; the struggle

between light and darkness ere Christianity diffused its peace and goodwill

; the social progress of the district, from the times when civil discord

destroyed the happiness of the family circle, retarding agriculture and

commerce; and the conviction that forces itself upon the mind that we are

under the deepest obligation to maintain our civil and religious privileges

at home, and to extend them to all for the promotion of their happiness, and

the glory of the ‘ Father of lights,’ who has graciously bestowed upon us

these invaluable blessings! Or if we wander through the solemn forests, or

traverse the long stretches of brown heath, where the silence is only broken

by the hum of the bee among its purple hills, new ideas are suggested and

emotions awakened. Or if we ascend the rugged summits of the hills, whence

the works of men are scarcely discernible, and a boundless prospect opens on

every side, what heart does not feel the insignificance of human grandeur,

or can resist the impression of the wisdom, power, and goodness of Him ‘who

weighed the mountains in scales, and the hills in a balance,’ or fail to

long for the time when ‘ the mountains and hills shall break forth into

singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands ’!"

According to Skene, there are traces of Roman works on the Spey at Pitmain

(within a mile of Kingussie), “on the line between the Moray Firth and

Fortingall,” indicating, in his opinion, that Severus the Roman emperor,

after his campaign in Britain in the third century, had returned with a part

of the Roman army through the heart of the Highlands. In 1380 the Chartulary

of Moray informs us that “ A Stewart, Lord of Badenoch, holds his court at

Kingussy, and among others that attended is Malcolme le Graunt.”

In the ‘Survey of the Province of Moray,’ published in 1798, it is stated

that several years previously a mine had been opened where some pieces of

very rich silver ore were dug up, but that no attempt had been made to

ascertain whether it would be worth working or not.3 In the statistical

account of Kingussie it is related “ that the parish contains, likewise,

some Druidical circles, and the appearance of a Roman encampment. This last

is situated on a moor between the Bridge of Spey and Pitmain. In clearing

some ground adjacent, an urn was found full of burnt ashes, which was

carefully preserved, and is still extant. A Roman tripod was also found some

years ago, concealed in a rock, and is deposited in the same hands with the

urn.” What has become of the urn and the tripod I have been unable to

ascertain.

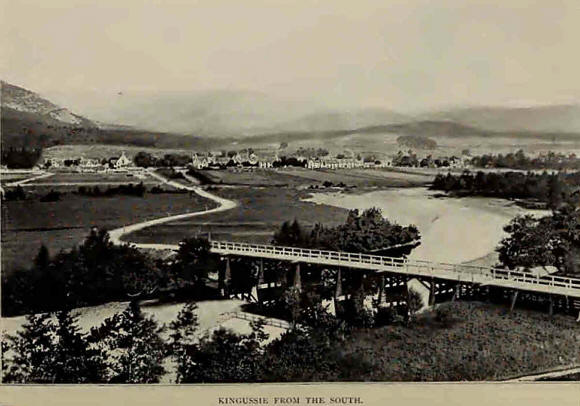

The village of Kingussie was founded towards the close of last century by

Alexander, the fourth Duke of Gordon, as an intended seat of woollen

manufactures. From the want, however, of sufficient capital and the means of

transit at the time, this scheme unfortunately proved unsuccessful. Under

the General Police and Improvement Act of 1862 the village was in 1866—soon

after the opening of the Highland Railway—formed into a burgh, and during

the last few years it has, through the energy and enterprise of the

inhabitants, progressed to such an extent that it bids fair to become one of

the most flourishing Highland villages of its size north of the Grampians.

Beautifully situated at such a high altitude in a fine open valley of the

Spey, bordered on one side by the magnificent range of the Grampians and by

the Monadhliath range on the other, and noted for its pure and invigorating

mountain air, it is gradually becoming one of the most attractive and

popular summer resorts in the Highlands. An eminent London physician has

compared the exhilarating effect of inhaling the Badenoch air to that of

imbibing the most sparkling champagne—barring in the former case the

slightest risk either of the loss of one’s equilibrium or of a headache next

morning. Witness also the spirited lines of the ever-bright and genial

Professor Blackie commemorative of a lengthened visit to Kingussie in the

summer of:

“Tell me, good sir, if you know it—

Tell me truly, what’s the reason

Why the people to Kingussie

Shoalwise flock in summer season?

Reason? Yes, a hundred reasons:

Tourist-people are no fools;

Well they know good summer quarters,

As the troutling knows the pools.

Look around you ; did you ever

See such sweeps of mighty Bens,

With their giant arms enfolding

Flowery meads and grassy glens?

Come, oh come, in sunless chambers

Ye who plod with inky pens ;

Come, and give your eyes free outlook

On the glory of these Bens!

Here we dream no dreams, no paper

Here besmirch with inky care,

When we brush the mountain heather,

When we breathe the mountain air!

Come with me, ye Lowland lubbers,

Learn to knock at Nature’s door;

Peeping clerks and plodding scholars,

Start with me for Aviemore!

See that kingly Cairngorm,

From his heaven-kissing crown,

On the wealth of pine-clad valleys

Northward looking grandly down;

From his broad and giant shoulders,

From huge gap and swelling vein,

Through the deep snow-mantled corrie,

Pouring waters to the plain.

Or, if feast of Nature please thee

In her rich and pictured show,

Come with me to lone Glen Feshie,

When the grey crags are aglow.

With the broad sun westward wheeling;

Come and sit, and let thine ear

Drink the music of the waters

Rolling low and swirling clear.” |