|

“But thou hast a shrine,

Kingussie,

Dearer to my heart than all

Rocky strength and grassy beauty

In Glen Feshie’s mountain-hall;

E’en thy granite Castle Cluny,

Where the stout old Celtic man

Lived the father of his people,

Died the noblest of his clan.

Many eyes were red with weeping,

Many heads were bowed with grief,

When, to sleep beside his fathers,

Low they laid their honoured chief.”

—Blackie.

THE LAST OF THE OLD JACOBITE

CHIEFS.

CLUNY MACPHERSON, C.B., Chief of Clan Chattan

BORN 24th APRIL 1804; DIED 11th JANUARY 1885.

AT Cluny Castle, in Badenoch,

on the second Sunday of the year, there “fell asleep,” full of years and

full of honours, the venerable Cluny Macpherson, “the living embodiment,” as

he had been justly termed, “of all the virtues of the old patriarchal

Highland chief.” His unexpected death has not only awakened feelings of the

deepest sorrow among his clansmen and natives of Badenoch all over the

world, but has left a blank in the public and social life of the Highlands

which will probably never be filled up.

His removal is indeed that of an ancient landmark. In days when so much is

said and done tending to set class against class, and leading certain

sections of the public to regard the interests of landlord and tenant as

hostile, a state of society in which their interests were recognised as

identical deserves to be studied. In their best form the mutual relations

existing between a chief and his clansmen produced this unity in a manner to

which, in the present day, we shall vainly seek a parallel. “ I would

rather,” said MacLeod of MacLeod of the time to Johnson, on the occasion of

the great lexicographer’s tour in the Hebrides in 1781, —“I would rather

drink punch in the houses of my people than be enabled by their hardships to

have claret in my own.” A more striking example of this patriarchal feeling

could not be found than in the affection which bound Cluny Macpherson to his

clan and his clan to him. In their relations with their people, the old race

of Highland chiefs, of whom Cluny Macpherson was such a noteworthy

representative, really held in effect the words of the well-known and

patriotic Highlander, Sheriff Nicolson, as part, so to speak, of their

creed:—

“See that thou kindly use

them, O man!

To whom God giveth

Stewardship over them, in thy short span,

Not for thy pleasure.

Woe be to them who choose for a clan

Four-footed people.”

Born on the 24th of April

1804, Cluny, as he was popularly known all over the Highlands, had at the

time of his death entered his eighty-first year. He was the representative

of the ancient chiefs of Clan Chattan, embracing, in that general

appellation, the Macphersons, Mackintoshes, Macgillivrays, Shaws,

Farquharsons, Macbeans, Macphails, Clan Terril, Gows (said to be descended

from Henry the Smith of North Inch fame), Clarks, Macqueens, Davidsons,

Cattanachs, Clan Ay, Nobles, Gillespies; and was the twentieth Chief in

direct succession from Gillicattan Mor, the head or Chief of the clan who

lived in the reign of Malcolm Canmore. He succeeded to the chiefship of the

clan, and to the Cluny estates, on the death of his father in 1817, and thus

possessed the estates for the long period of nearly seventy years. A very

interesting fact in connection with his boyhood, carrying us back to the

third decade of the present century, is that Sir Walter Scott, in a letter

to Miss Edgeworth, describes him as “a fine spirited boy, fond of his people

and kind to them, and the best dancer of a Highland reel now living.” In

1832 Cluny married Sarah Justina, a daughter of the late well-known Henry

Davidson, Esq. of Tulloch, who now cluny’s early manhood survives him with

an unbroken family circle of four sons and three daughters.

The son of a gallant officer who fought in the American War of Independence;

grandson of the devoted “Ewen of Cluny,” who died in exile after the ’45;

great-grandson of Simon Lord Lovat, who suffered in the same cause, and

great-great-grandson of the heroic Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, Cluny always

maintained with true dignity the fame of his ancestry, and inherited all

their military ardour. To a quaint old engraving of Sir Ewen at Cluny

Castle, the following just and appropriate lines are appended : —

“The Honest Man, whom Virtue

sways,

His God adores, his King obeys;

Does factious men’s rebellious pride

And threat’ning Tyrants’ rage deride;

Honour’s his Wealth, his Rule, his Aime,

Unshaken, fixt, and still the same.”

In his early manhood Cluny

served his country as an officer in the 42d Royal Highlanders, the famous

Black Watch. From the institution of the Volunteer Force in 1859 down to

within two or three years of his death he acted as Lieutenant-Colonel of the

Inverness-shire Highland Rifle Volunteers. In that capacity he attended the

Royal Review in Edinburgh in 1881, and although then in his seventy-seventh

year, he kept the head of his regiment in spite of the fearful weather,

discarding even the use of a plaid as a protection. Riding along Princes

Street with the Inverness Volunteers, the brave old Chief, with his courtly

and soldierly bearing, was a conspicuous figure in the procession, and was

singled out for repeated rounds of enthusiastic cheering. On his retirement

his regiment presented him with a sword of honour with an appropriate

inscription.

As indicating the interest taken by Cluny in everything affecting the

prosperity of the wide district over which his influence extended, and the

recognition of his character and position, it may be sufficient to mention

that he was president or was otherwise closely associated with almost every

public and local association or institution in the Central Highlands. In his

delightful book, ‘Altavona,’ Professor Blackie makes his Alter Ego say of

Cluny, “He is the genuine type of the old Scottish chief, the chief who

loves his people, and speaks the language of the people, and lives on his

property, and delights in old traditions, in old servants, in old services,

and old kindly usages of all kinds.” It has been justly said that into all

his duties Cluny carried with him a flavour of the olden times, a mingled

homeliness, courtesy, and simple dignity that conveyed a remarkable

impression impossible to describe, but characteristic and memorable. In the

Highland dress, surmounted by the bonnet and eagle’s feather of the chief,

with his firm, erect, athletic figure, no more graceful specimen of Highland

physique could be anywhere seen.

While a conspicuous figure at all public gatherings in the Highlands,

nowhere was Cluny seen to more advantage than at his own castle, surrounded

by his genial and happy family, dispensing, with a genuine kindness and

courtesy that never failed, true Highland hospitality to the many friends

and clansmen who flocked to it from all parts of the kingdom. Substitute the

one castle for the other, and the touching words of Dean Stanley apply

almost as appropriately to Cluny Castle as to the Castle of Fingask :—

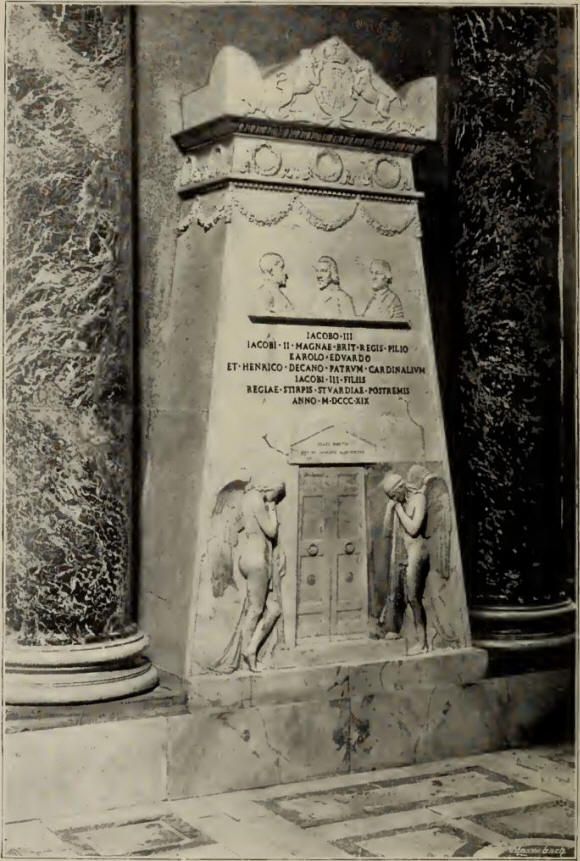

“Who that had ever seen the delightful Castle of Cluny, explored its

inexhaustible collection of Jacobite relics, known its Jacobite inmates, and

heard its Jacobite songs, did not feel himself transported to an older world

with the fond remembrance of a past age, of a lost love, of a dear though

vanquished cause? What Scotsman—Presbyterian though he be—is not moved by

the outburst of Jacobite-Episcopalian enthusiasm which enkindled the last

flicker of expiring genius when Walter Scott murmured the lay of Prince

Charlie by the Lake Avernus, and stood wrapt in silent devotion before the

tomb of the Stuarts in St Peter’s?”

It was worth going a long day’s journey to hear Cluny with his simple grace

and dignity narrating incidents of the Jacobite days of other years, the

hair-breadth escapes of his grandfather, and describing the many interesting

and historical relics the castle contains. Among these relics, carefully

treasured, is the Black Chanter or Feadan Dubh of the clan, on the

possession of which the prosperity of the house of Cluny is supposed to

depend. Of the many singular traditions regarding it, one is that its

original fell from heaven during the memorable clan-battle fought between

the Macphersons and the Davidsons in presence of King Robert III., his

queen, and nobles, on the North Inch of Perth in 1396, and that being made

of crystal it was broken by the fall, and the existing one made in fac-simile.

Another tradition is to the effect that this is the genuine original, and

that the cracks were occasioned by its violent contact with the ground. Be

the origin of the Feadan Dubh what it may, it is a notable fact that whether

in consequence of its possession, or of their own bravery, no battle at

which the Macphersons were present with the great standard or “green banner”

of the clan, and the chief at their head, was ever lost. One of the Clan

Chattan battles was fought at Invernahaven in the neighbourhood of Kingussie

in 1386, on which occasion the Macphersons, coming to the rescue of their

kinsmen the Mackintoshes, saved the honour of the Clan Chattan and the

Mackintosh section from almost utter annihilation at the hands of their

opponents, the hitherto victorious Camerons. The battle of the Inch at

Perth, fought ten years subsequently, has been rendered familiar to general

readers through the pages of Scott’s ‘ Fair Maid of Perth.’ The Clan Chattan

took part in the great national battles of Bannockburn and Harlaw, the

Macphersons in the latter, under their chief, Donald Mor, fighting “with my

Lord Marr against M'Donald.” “Duncan persoun,” one of Cluny’s ancestors, was

one of the chiefs seized and imprisoned by James I. at a Parliament which he

had summoned to meet him at Inverness in 1427. The Macphersons were out in

great force under Montrose and Dundee. They were also present at the battle

fought at Mulroy, in Lochaber, in the year 1688—the last clan-battle in the

Highlands—where, as narrated by Sir Walter Scott, they rescued the Laird of

Mackintosh (who had been defeated and made prisoner) from the hands of his

ferocious captors, the Macdonalds of Keppoch, and afterwards escorted him in

safety to his own proper territory.

The Macphersons were again

out in the Rising of 1715, and with a loyalty that “no gold could buy nor

time could wither,” took a distinguished part thirty years later in the

gallant but ill-fated attempt of Prince Charlie to regain the crown of his

ancestors:—

“Whom interest ne’er moved

their true king to betray,

Whom threat’ning ne’er daunted, nor power could dismay ;

They stood to the last, and, when standing was o’er,

All sullen and silent they dropped the claymore,

And yielded, indignant, their necks to the blow,

Their homes to the flame, and their lands to the foe.”

It is related that before the

battle of Culloden an old witch or second seer told the Duke of Cdmberland

that if he waited until the Bratach Uaine, or green banner, came up he would

be defeated. Ewen of Cluny was present at the battle of Prestonpans with six

hundred of his clan, and accompanied the Prince during his march into

England. On the Prince’s retreat into Scotland, Cluny with his men put two

regiments of Cumberland’s dragoons to flight at Clifton, fought afterwards

at the battle of Falkirk, and was on his way to Inverness with his clan to

join the Prince when flying fugitives from Culloden met him with the

intelligence of that sad day’s disaster.

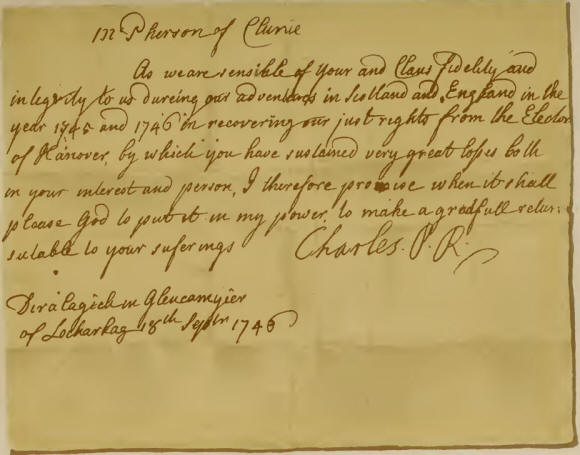

Another relic at Cluny Castle no less carefully treasured is the autograph

letter, of date 18th September 1746 (which is given here in facsimile),

addressed by Prince Charlie to Cluny of the ’45 just on the eve of their

parting before the Prince escaped to France.

To Cluny of the ’45 might, mutatis mutandis, be appropriately applied Sir

David Brewster’s touching epitaph on a Scottish Jacobite:—

“To Scotland’s king I knelt in homage true,

My heart—my all I gave—my sword I drew;

Chased from my hearth, I reached a foreign shore,

My native mountains to behold no more—

No more to listen to Spey’s silver stream—

No more among its glades to love and dream,

Save when in sleep the restless spirit roams

Where Ruthven crumbles, and where Pattach foams.

From home and kindred on Albano’s shore,

I roamed an exile till life’s dream was o’er—

Till God, whose trials blessed my wayward lot,

Gave me the rest—the early grave—I sought;

Showed me, o’er death’s dark vale, the strifeless shore,

With wife, and child, and king, to part no more.

O patriot wanderer, mark this ivied stone,

Learn from its story what may be thine own:

Should tyrants chase thee from thy hills of blue,

And sever all the ties to nature true,

The broken heart may heal in life’s last hour,

When hope shall still its throbs, and faith exert her power.”

In view of the very prominent

part the clan took in the Risings of the ’15 and the ’45, and the sufferings

of his grandfather and greatgrandfather in the cause, it is not surprising

that Jacobite leanings should have developed themselves in Cluny at an early

period of his life. The bloodthirsty vindictiveness displayed towards a

defenceless people after the battle of Culloden, by the Duke of Cumberland

and the Government of the day, is almost unexampled in history.

“The cruelties,” says Chambers, “were such that, if not perfectly well

authenticated, we could scarcely believe to have been practised only a

century ago in our comparatively civilised land. Not only were the mansions

of the Chiefs Lochiel, Glengarry, Cluny, Keppoch, Kinlochmoidart, Glengyle,

Ardshiel, and many others, plundered and burned, but those of many inferior

gentlemen, and even the huts of the common people, were in like manner

destroyed. The cattle, sheep, and provisions of all kinds were carried off

to Fort Augustus. In many instances the women and children were stripped

naked, and left exposed; in some, the females were subjected to even more

horrible treatment. A great number of men, unarmed and inoffensive,

including some aged beggars, were shot in the fields and on the

mountain-side, rather in the spirit of wantonness than for any definite

object. Many hapless people perished of cold and hunger amongst the hills.

Others followed, in abject herds, their departing cattle, and at Fort

Augustus begged, for the support of a wretched existence, to get the offal,

or even to be allowed to lick up the blood of those which were killed for

the use of the army. Before the 10th of June the task of desolation was

complete throughout all the western parts of Inverness-shire; and the curse

which had been denounced upon Scotland by the religious enthusiasts of the

preceding century was at length so entirely fulfilled in this remote region

that it would have been literally possible to travel for days through the

depopulated glens without seeing a chimney smoke or hearing a cock crow"

Of a corps under the command of Lord George Sackville, Browne relates :—

“Not contented with destroying the country, these bloodhounds either shot

the men upon the mountains, or murdered them in cold blood. The women, after

witnessing their husbands, fathers, and brothers murdered before their eyes,

were subjected to brutal violence, and then turned out naked with their

children to starve on the barren heaths. A whole family was enclosed in a

barn, and consumed to ashes. So alert were these ministers of vengeance,

that in a few days, according to the testimony of a volunteer who served in

the expedition, neither house, cottage, man, nor beast was to be seen within

the compass of fifty miles: all was ruin, silence, and desolation. Deprived

of their cattle and their small stock of provisions by the rapacious

soldiery, the hoary-headed matron and sire, the widowed mother and her

helpless offspring, were to be seen dying of hunger, stretched upon the bare

ground, and within view of the smoking ruins of their dwellings.”

It is instructive to contrast that inhuman vindictiveness with the spirit in

which the descendants of Highlanders, so cruelly and mercilessly persecuted,

have since so nobly fought and died for their country on many a

battle-field. To quote the famous eulogy on the Highland regiments uttered

in Parliament in 1776 by William Pitt, afterwards Lord Chatham :—

“I sought for merit wherever it could be found. It is my boast that I was

the first Minister who looked for it, and found it, in the mountains of the

north. I called it forth, and drew into your service a hardy and intrepid

race of men ; men who, when left by your jealousy, became a prey to the

artifices of your enemies, and had gone nigh to have overturned the State,

in the war before last. These men, in the last war, were brought to combat

on your side; they served with fidelity, as they fought with valour, and

conquered for you in every quarter of the world.”

At the advanced age of nearly eighty years Cluny’s great-grandfather was

beheaded in the Tower of London. After being hunted in the mountain

fastnesses of Badenoch for the long period of nine years, his grandfather

escaped from his relentless pursuers only to die in exile. It was very

natural, therefore, that Cluny’s Jacobite sympathies should have remained

with him to the end. An instance of his leanings in this direction may be

appropriately told. At a school inspection in Kingussie a few years ago, in

the course of one of his usually happy and encouraging little speeches to

the children, he mentioned that, in listening to the examination in history,

some of the words used had jarred upon his ear. “In Badenoch,” he said, “it

is not common to call Prince Charlie ‘the Pretender.’ I should advise you

henceforth to call him by his name, Prince Charles Edward, the King over the

water!”

With all his hereditary Jacobite sympathies, the Queen had no more loyal and

devoted subject than Cluny in her wide domains; of his four sons he devoted

three to her service. On the occasion of the first Royal visit to the

Highlands in August 1847, her Majesty and Prince Albert, with the Prince of

Wales and the Princess Royal, occupied for a time Cluny’s beautiful

residence of Ardverikie, overlooking Loch Laggan, on an island in the middle

of which Fergus, “the first of our kings,” had his hunting - lodge.

Accompanied by Prince Albert and the Royal children, her Majesty paid a

visit to Cluny Castle and examined the shield and other relics of Prince

Charlie with the greatest interest. Meeting Cluny frequently at the time,

the Queen was most favourably impressed with his polished manners and

chivalrous courtesy, and he subsequently received many gracious and

flattering marks of her regard. After the lapse of nearly forty years since

her first meeting with him, her Majesty showed her long-continued regard for

the venerable Chief by conferring upon him the distinction of the Order of

the Bath, which, as coming from her own gracious hands, he very highly

prized. It was a source of special gratification to him that he lived to see

two of his sons commanding two of the most distinguished regiments in her

Majesty’s service— the eldest, Colonel Duncan, commanding the famous Black

Watch ; and the second, Colonel Ewen, commanding the 93d Highlanders. They

have both seen a great deal of active service; and worthily and honourably

have they maintained the ancient fame and prowess of their forefathers.

Colonel Duncan, who now succeeds to the chief-ship and to the Cluny estates,

has had an eminent military career, and has had a pension for “distinguished

service” conferred upon him, besides the distinction of the Order of the

Bath. Leading the Black Watch, he was wounded at Coomassie, in the Ashantee

war; and at the head of that famous regiment in the Egyptian war, two or

three years ago, was “the only man who rode over Arabi’s intrenchments at

Tel-el-Kebir.”

On their “golden wedding-day,” in December 1882—the fiftieth anniversary of

Cluny’s marriage to the lady who had for the long period of half a century

shared with him the affection and loyalty of his clan and tenantry—the

venerable and happy pair received an ovation such as seldom, if ever

previously, was witnessed in the Highlands. Congratulatory addresses,

couched in the warmest terms, were presented by all the public bodies in the

county with which Cluny was connected. In addition to deputations from these

bodies, a large and distinguished party of clansmen and friends, headed by

Sir George Macpherson-Grant and the veteran soldier, General Sir Herbert

Macpherson, waited upon Cluny and his lady and presented them with a

beautifully illuminated address, along with a magnificent work of art in the

form of a massive silver candelabrum or centrepiece, costing in all between

£600 and £700. A sturdy oak springing from the heather forms the stem of the

centrepiece, from which radiate at the top nine branches. At its foot is

placed a group representing one of the most striking and characteristic

incidents in the history of the famous Cluny of the “Forty-five.” Sir Hector

Munro—the officer in command of the party in search of the fugitive

chief—mounted on his steed, is questioning Cluny, who, disguised as a

servant, had been holding the bridle of Sir Hector’s horse during the

search, as to the whereabouts of his supposed master. Sir Hector asks if he

knows where Cluny is. The reply given is, “I do not know, and if I did I

should not tell you.” Sir Hector rewards the supposed servant for his

fidelity.

The address expressed on the part of the general body of subscribers their

warm appreciation of the admirable way in which Cluny had for upwards of

half a century, “with a grace and dignity peculiarly your own, discharged

every public and private duty devolving on you as a constant resident in

your native county, which has won for you the universal popularity you

happily enjoy.” On the part of his own “faithful and attached clan,” allied

to him “by closer ties and sympathies,” the address specially recorded

“their love and veneration for their dear old patriarchal Chief, and their

pride in him as representative of all that they and their forefathers have

ever held most precious as children of one race.”

No better exponent of the feelings and sentiments of the general body of

subscribers than Sir George Macpherson-Grant, himself a chieftain of the

clan,1 could possibly have been selected :—

Cluny’s “golden wedding.”

“This address,” said Sir George, in making the presentation to Cluny,

“speaks of your clansmen. I hardly know what to say on such a point as that

which the use of the word on an occasion like the present calls up. I have

deep feelings on the subject. In these days we don’t hear—and perhaps it is

for our good—very much of the clan, of the clansmen, of the clanship, and of

their varied mutual relationships, and all that at one time was connected

with it. But I have the feeling in my breast that as long as the clan

exists—I care not how it should be shown—the sense of the duty which

clansmen owe to their chief can never be torn from our hearts. We cannot

show our sense of that duty, that loyalty, that affection, in the same way

as it has frequently been shown before; but although the outward

manifestation is not the same, the spirit of it remains the same in the

hearts of us all. Allow me one personal remark. As a neighbouring

proprietor, and as an old friend of your family, it gives me the greatest

possible pleasure to take part in the proceedings of to-day. I know that by

you and the Lady of Cluny the proceedings of to-day must be viewed with

mixed feelings. Your thoughts must turn to-day not only to many years of

bygone times, but they must also be directed to what we hope may be many

happy years in the future. And it is my wish, and it is the wish of all here

present, that as the end approaches, you, surrounded by a happy and united

family, honoured and respected by all who know you—honoured by your

sovereign, as we know you are, and respected and beloved by your clansmen—I

say, we fondly hope that you may regard the last days of your life as the

brightest and the happiest of the days you have remembered. I have only now

to ask you to accept this address, and I have to ask you also to accept the

memorial, the sketch of which you see before you. It occurs to me that

perhaps, as you look at that [pointing to the picture of Sir Hector Munro,

who searched Badenoch for Cluny of the ’45], the feeling may come over you

that there were leal hearts in Badenoch in the days when English gold could

not tempt the Highland people to give up your distinguished ancestor or the

Prince, to whose cause he was so faithfully attached. When that feeling

comes over you, will you read this address which I now present to you, and

\^hich is signed by over three hundred men throughout the empire and beyond

it? And will you believe me, that although there is no king’s gold put forth

to buy the Highlanders now, there are as leal hearts in Badenoch now as ever

there were in the days of your forefathers?”

In the course of a touching reply by Cluny—

“It has been”—said the venerable Chief, with deep emotion—“It has been my

delight and that of my wife to dwell among our own people, and to endeavour

so to act in every relation of life as to secure their affection and

respect. Nothing could give us greater satisfaction in the evening of life

than the consciousness of having so acted ; and nothing to us is more

gratifying than the strong testimony we have now received that we have in

some measure succeeded in doing our duty, and retaining the confidence and

goodwill of so large a circle of friends. We cannot expect at our time of

life long to take an active part in the duties of our station; but you may

all rest assured that we shall continue through life to take the deepest

interest in everything that relates to and that will promote the welfare of

the district where our home is, and where we have passed so many happy

years, and which, to us, no place on earth can compare. To my clansmen I

will say this, that though the days are past when the gathering cries of

clans resounded throughout the Highlands, and the clansmen hastened to the

banners of their chiefs, there is no abatement in their old clannish feeling

of devotion, nor of affection and pride on the chief’s part towards and in

his clansmen. These feelings it has been my pride and pleasure to cherish ;

and the sentiments you, my clansmen, have expressed towards your Chief will,

I am sure, find an echo in the hearts of clansmen all the world over.”

The subscribers to the presentation numbered between three and four hundred,

and embraced all the historic names in the Highlands. The existing chiefs of

clans are nearly all represented in the list: Cameron of Lochiel, The

Chisholm of Chisholm, Lord Lovat (Chief of the Clan Fraser), the Earl of

Seafield (Chief of the Clan Grant), Lord Macdonald of the Isles, Mackintosh

of Mackintosh, MacLeod of MacLeod, and Sir Robert Menzies, all old friends

or neighbours linked with many memories of the days of other years. The

Macphersons are represented by one hundred names. Had time permitted

communication with clansmen in the Australian colonies, the names would have

been still more numerous. The letters received by Cluny at the time from

clansmen in all parts of the world, breathing the warmest spirit of

devotion, were intensely gratifying to him. As evidencing the deep regard

entertained for him, not only in this country, but beyond the limits of the

United Kingdom— extending even to our American cousins—not the least

interesting circumstance in connection with the presentation was the fact

that spontaneous contributions were cabled by the Speaker of the Senate of

Canada (Sir D. L. Macpherson) from Canadian clansmen, and that similar

contributions were cabled by a barrister of high standing in Washington (Mr

John D. Macpherson) from clansmen in the United States.

A consistent Conservative all his life, Cluny was ever courteous and

tolerant to all who differed from him, whether in Church or in State—

disarming contention, as he frequently, quietly, and happily did, with the

remark, “We must agree to differ.” A loyal and devoted Presbyterian, he was

no sectarian. Men of all Churches and of all ranks honoured him. In the

management of his estates the maxim, “Live and let live,” which he often

quoted, was his ruling principle. During his long possession, evictions or

summonses of removal were never heard of, and cluny’s death and funeral.

practically there were no arrears of rent. He, winter and summer, ever loved

to dwell “among his own people.” It is no exaggeration to say that every

tenant and crofter on his estates were familiarly known to him by name. In

him were the Scriptural precepts, “Be pitiful, be courteous,” beautifully

exemplified. He never passed the humblest labourer on his estates without,

when opportunity offered, some happy salutation in the old mother tongue, so

dear to Highlanders. Less than a week before his death he expressed to the

writer feelings of the warmest kind towards his clan and tenantry. Among

other matters, he spoke about the meeting of Highland proprietors which had

been arranged by his kinsman, Lochiel, to take place at Inverness the

following week, in connection with the crofter question, observing that he

was too old to attend. “You know,” he said, “that I am on the best of terms

with my tenants and crofters, and I do not consider my presence necessary in

any case.” Encouraging, as he ever did within reasonable and well-regulated

bounds, all the innocent and manly pastimes of our forefathers, Cluny was in

the habit of annually giving a “ball play,” or shinty match, to his people.

On Christmas Day (old style), five days before his death, the “ball play”

took place as in previous years. The day happened to be very stormy, with

blinding showers of snow. The aged Chief would not be dissuaded by loving

counsels from attending as usual, remarking that while strength was spared

to him he considered it simply his “duty” to be present at all such happy

gatherings of his people. Accompanied by the loving partner of his long and

happy wedded life, he accordingly drove to the field, and they were both

received with the genuine Highland enthusiasm ever evoked by the presence of

the venerable pair at such gatherings. In response, Cluny made a happy

little speech in Gaelic, expressive of the pleasure it always afforded him

to be present with his people, participating, as he had always endeavoured

to do, in their joys as well as in their sorrows. Although Cluny’s exposure

to the piercing blasts on that occasion—dictated, as such exposure was, by a

lifelong regard and consideration for his people—did not, it is believed,

hasten the end, yet that end was very near. Within five days an attack of

bronchitis had developed itself to such an extent that on Sunday, the nth of

January, the venerable Chief passed calmly and peacefully to his rest.

Attended by a large gathering, representative of all classes, embracing many

of the greatest historical names in the Highlands, the funeral took place on

Saturday, the 17th of January, amid manifestations of the deepest sorrow.

The scene was altogether peculiarly touching and impressive. In the spacious

hall of the castle lay the coffin, bearing on a brass plate the following

inscription :—

“EWEN MACPHERSON OF CLUNY

MACPHERSON,

CHIEF OF CLAN CHATTAN, C.B.,

DIED 11TH JANUARY 1885, IN HIS EIGHTY-FIRST YEAR.”

On the top of the coffin were

placed the sword and well-known bonnet of the Chief, embowered with wreaths,

loving tributes of affection from relatives, friends, and clansmen.

Prominent among such tributes was one from his old regiment, the Black

Watch. Around the hall were the numberless historical relics of the past, in

which the dead Chief took such an interest. Suspended above the coffin was

the famous Bratach Uaine, or green banner of the clan, torn and dimmed with

the stains of many a battle-field, but with no stain of dishonour. While

descending the steps leading from the hall, the eyes of not a few present

filled with tears as they recalled many a happy greeting or parting word,

warm from the heart, uttered by the lips now closed for ever. As the funeral

procession moved slowly along the avenue to the quiet and secluded

burial-place of the family—the snow muffling the measured tread of the

mourners—the solemn and impressive stillness was broken by the plaintive

notes of the bagpipe, the pealing lament of the pibrochs awakening, as if in

responsive sympathy, the wailing echoes of Craig Dhu—the Craig Dhu so

closely identified with the Macphersons as their war-cry in turbulent days

happily long gone by. Thus appropriately was the venerable Chief “gathered

to his fathers” under the shadow of the “everlasting hills” he loved so

well. Conscious that beneath the whitened sod that wintry day there had been

laid one of the truest and most patriotic hearts that ever beat in the

Highlands of Scotland, his friends and clansmen left all that was mortal of

their dear old Chief in his last resting-place, the words of the old Gaelic

Coronach—so inexpressibly touching to all Highlanders—as they sorrowfully

wended their way homeward, still sounding in their ears:-

“Cha till, cha till, cha till mi tuilleadh,

An cogadh n’an sith, cha till mi tuilleadh;

Le h-airgiod no ni cha till mi tuilleadh

Cha till gu brhth gu la na cruinne.”

(I’ll return, I’ll return, I’ll return no more,

In war or in peace, I’ll return, no never;

Neither love nor aught shall bring me back never

Till dawns the glad day that shall jjoin us for ever.)

|