|

“I am gone mad about them. It

is impossible to conceive that they were written by the same man that writes

me these letters. On the other hand, it is almost as hard to suppose, if

they are original, that he should be able to translate them so admirably. In

short, this man is the very demon of poetry, or he has lighted on a treasure

hid for ages.”—Gray.

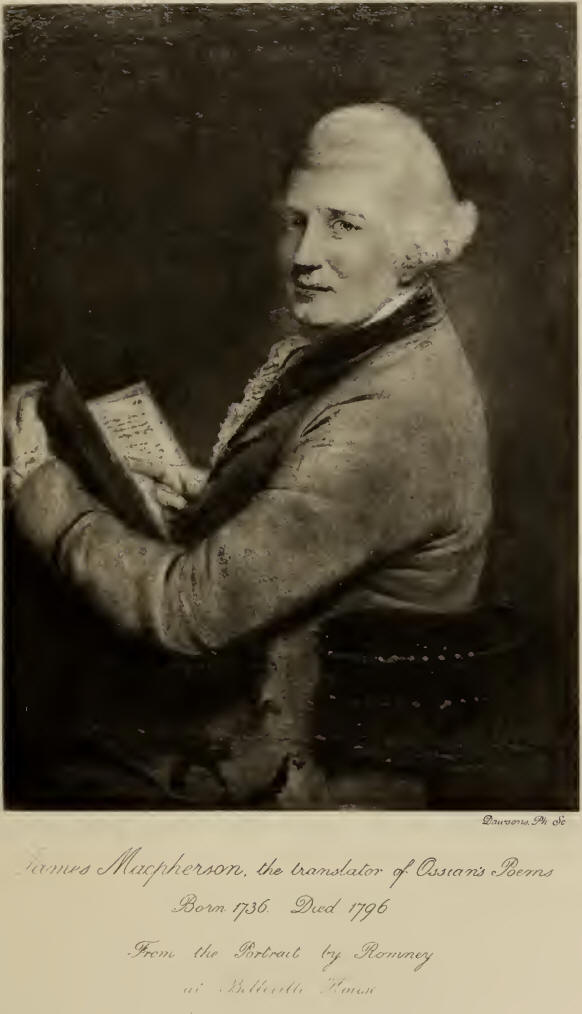

Ruthven, in the parish of

Kingussie, on the north side of the Grampians—about half-way on the great

Highland Road between Perth and Inverness—was born, in 1736, James

Macpherson, who at the early age of twenty-four attained such celebrity as

the translator of Ossian’s poems, and of whom such a true poet as the author

of the immortal “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” so wrote in the seventh

decade of last century. In a letter or memorandum addressed by Alexander

Clark, “writer at Ruthven in Badenoch,” to the Rev. John Anderson, minister

of Kingussie (one of the translator’s executors), dated 25th October 1797,

Clark states that “the late James Macpherson of Balville, Esquire, was born

27th October 1736,1 and dyed in February 1796, in the fifty-ninth year of

his age. His father’s name was Andrew Macpherson, son to Ewan Macpherson,

brother to the then Macpherson of Cluny. His mother’s name was Ellen

Macpherson, daughter of a respectable tacksman of the second branch of the

Clan.”

In the immediate neighbourhood of the old village of Ruthven, in the

lordship of Badenoch, stood Ruthven Castle—once the great stronghold of the

Comyns—where after the battle of Culloden the remnant of the ill-fated

followers of Prince Charlie met, never more to reassemble. To prevent its

falling into the hands of the Royalists the castle was burnt by the

fugitives from Culloden, and the flames would in all probability have been

witnessed by Macpherson, then a boy of nearly ten years old.

Receiving the earlier rudiments of his education at home, Macpherson was

afterwards sent to the grammar-school of Inverness. Of a good family and

destined for the Church, he subsequently attended in succession the

Universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh, and for a short time after the

completion of his curriculum filled the honourable position of parochial

schoolmaster at Ruthven, then a place of considerable educational

distinction. Writing in 1760, “I well remember,” says Shaw, the historian of

Moray, “when from Speymouth (through Strathspey, Badenoch, and Lochaber) to

Lorn there was but one school—viz., at Ruthven in Badenoch—and it was much

to find in a parish three persons that could read or write.”

Besides contributing fugitive pieces to the ‘ Scots Magazine ’ of the time,

Macpherson in 1758, when only twenty-two years of age, published a poem in

six cantos entitled “ The Highlander,” which, though not calculated to set

either the Thames or the Water of Leith on fire, was sufficient, considering

the youth of the author, to make him known to a few as a literary aspirant

of some promise.” David Hume the historian describes him soon afterwards as

“ a modest, sensible young man, not settled in any living, but employed as a

private tutor in Mrs Graham of Balgowan’s family—a way of life of which he

is not fond.” In October 1759, Dr Carlyle of Inveresk happened to visit the

Spa at Moffat, where he met the well-known John Home, the author of

‘Douglas.’ In the course of conversation between them allusion was made to

transcripts of Gaelic poems in the possession of Macpherson, who was at the

time resident at the Spa with his pupil, young Graham of Balgowan,

afterwards Lord Lynedoch. Home was so impressed with the amount of poetical

genius displayed by the portions submitted to him of Mac-pherson’s

translations, that these were forwarded to Dr Blair, the leading literary

arbiter of the time in the Scottish metropolis. So deep an interest did that

great literary theologian take in the translations, that Macpherson was

subsequently urged to give translations of all the fragments of Ossianic

poetry he could collect, with the result that in the following year (1760) a

small volume was published, under Dr Blair’s patronage, entitled ‘ Fragments

of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland and translated from

the Gaelic or Erse Language.’ Such was the furore which the publication of

these fragments created in the literary world that Macpherson in 1762, as

the result of his further labours as a collector and translator, published ‘

Fingal; an ancient Epic Poem in Six Books, with several other Poems,

composed by Ossian, the son of Fingal, translated from the Gaelic Language

by James Macpherson.’

“The reception,” says

Professor Blackie, “which this volume met with was more than sufficient to

spur the author to give the finishing touch without delay to his great work

of making the echoes of the old Celtic harp sweetly audible to Teutonic

ears. He worked on the maxim of striking the iron when it is hot, and next

year produced ‘Temora,’ an epic poem of larger range than ‘Fingal,’ along

with some minor poems. Thus his Celtic labours were completed, and his

European reputation as the Pisistratus or the Aristarchus of a Celtic Homer

established; and thus in a sudden and strange way, from a little flickering

light, so to speak, flitting over a Highland bog, he had become

metamorphosed into a jar strongly laden with electricity, and flashing forth

light and animation through the body and to the uttermost limbs and

flourishes of the intellectual world. Unquestionably he had good reason to

be satisfied; he had good reason to be proud; grave reason also to be

modest, and, as St Paul expresses it, to rejoice with trembling.”

Macpherson’s subsequent literary and public career is thus briefly sketched

in the admirable introduction by Mr Eyre-Todd to the edition of the Poems of

Ossian, recently published as one of the series of ‘The Canterbury Poets’ :—

“In 1764 he went out to Pensacola as private secretary to the Governor

there. A difference however arising, he gave up the position, made a tour

through the West India Islands, and returned to London in 1766 with a

pension of £200 a-year. In 1771 a volume of Gaelic Antiquities which he

published, under the title of‘An Introduction to the History of Great

Britain and Ireland,’was most bitterly attacked upon its appearance. This,

with the similar abusive reception accorded his prose translation of the ‘

Iliad of Homer,’ published in two volumes in 1773, serves to show that the

attitude towards him of the literary cliques of

London had not altered in ten years. Better fortune must have attended the

publication in 1775 of his ‘History of Great Britain from the Restoration to

the Accession of the House of Hanover,’ with its companion volumes of

‘Original Papers’; for he is said to have received for this work the sum of

^3000. The Government also employed him to write two pamphlets in defence of

their action in the dispute and rupture with America. And on being appointed

agent in Britain for the Nabob of Arcot, he was provided with a seat in

Parliament.”

Failing in health, and seeking rest from the din and turmoil of political

and public life in the great metropolis, Macpherson retired at length to

Belleville, a beautiful estate which he had purchased in the parish of Alvie,

where, from a design by the “Adelphi Adams”—the famous architect of the

Edinburgh University buildings and St George’s Church, Edinburgh—he built a

handsome residence, situated within two or three miles of the spot where he

had been born, and commanding a magnificent view of the Grampians and the

valley of the Spey.4 Writing about half a century ago :—

“This mansion,” says Dr Carruthers, “was built by the poet when fame and

fortune had crowned him ; here he died, and here his eldest daughter, Miss

Macpherson, still resides. The situation of the house is beautiful,

commanding a full view of the valley and river, and bounded in front by two

ridges of hills, those of Invereshie, and the grey mountainous ridge of the

Grampians. The property was purchased about the year 1790 by the poet from

the family of Mackintosh of Borlum—a small Highland laird who disgraced his

clan and descent by highway robbery, committed not in the old legitimate

piratical way of levying blackmail, but by attacking travellers. His last

exploit was the robbery of a carriage, for which his associates were hanged;

but the prime offender contrived to escape to America. A cave is shown in

the rock where the bandit group used to watch the approach of travellers,

and rush down on their unsuspecting prey. The hillside is now covered with

trees, and near the mansion are some fine old elms, planted by

Brigadier-General Mackintosh, who was so intimately connected with the

public insurrection of 1715. The Brigadier was a rough soldier, trained to

war in France, and when confined in prison for his share of the rebellion,

he had the taste to order a row of trees to be planted along the roadside,

below his residence. The poet changed the name of the estate from Raitts to

Belleville, and pulling down the old Highland domicile, erected the present

stately structure.

“The interior of Belleville

House is handsomely furnished, and contains an excellent portrait of the

poet, and another of one of his intimate friends, Caleb Whitefoord, both by

Sir Joshua Reynolds. A view of the house and grounds by Thomson of

Duddingston, and two private portraits, also ornament the walls. In the

drawing-room is a small enamel portrait of Macpherson, the duplicate of one

painted for the Nabob of Arcot, also by Sir Joshua; and it is said to be

curious as the only miniature on ivory which the distinguished artist was

ever known to execute. The poet was a handsome man, six feet three inches in

height, of a fair and florid complexion, the countenance full and somewhat

inclining to the voluptuous in expression, but marked by sensibility and

acuteness. In the library is a curious trio of small volumes presented in

1785 by the Prince of Wales (George IV.) to the poet. They contain a

collection of the Della Cniscan poetry by Anna Matilda and others, which was

so unmercifully and so justly lashed by Gifford in his ‘Baviad and Mseviad.’

The volumes are splendidly bound in morocco, with a profusion of tawdry

gilding, and are placed in a small box, also covered with gilt morocco. We

looked with more interest on the different publications of Ossian from the

first work, a small duodecimo of about sixty pages, entitled ‘ Fragments of

Ancient Poetry, translated from the Gaelic or Erse Language,’ the quarto

‘Fingal’ and ‘Temora’ dedicated to the Earl of Bute, then the prime

dispenser of Government patronage, ‘in obedience to whose commands,’ as the

dedication states, ‘they were translated.’”

Mrs Grant of Laggan gives several interesting glimpses of the translator

from 1788 down to the date of his death in 1796. Writing from the manse of

Laggan—within twelve miles from Belleville—to a Mrs Brown, Glasgow, of date

10th October 1788, Mrs Grant says:—

“If you would tell me what you are all about, I would, for instance, tell

you how the Bard of Bards, who reached the mouldy harp of Ossian from the

withered oak of Selma, and awakened the song of other times, is now moving,

like a bright meteor, over his native hills; and, while the music of

departed bards awakes the joy of grief, the spirits of departed warriors

lean from their bright clouds to hear, and a thousand lovely maids descend

from the hill of roes, and pour forth the tears of beauty to the woes of

Malvina; while the fair mourner of Lutha rejoices in the presence of her

love, to hear his fame resound once more from Albion’s cliffs to the green

vales of Erin. This bard, as I was about to tell you, is as great a

favourite of fortune as of fame, and has got more by the old harp of Ossian

than most of his predecessors could draw out of the silver strings of

Apollo. He has bought three small estates in this country within these two

years, given a ball to the ladies, and made other exhibitions of wealth and

liberality. He now keeps a Hall at Belleville, his new-purchased seat, where

there are as many shells as were in Selma, filled, I doubt not, with much

better liquor.”

Writing to a friend on 10th October 1790, Mrs Grant mentions that she was

then “flattered with a prospect of getting franks from Fingal” —a familiar

name given in Badenoch to the translator—and she proceeds :—

“Mr Grant was at Belleville visiting Fingal, in the beginning of this week.

That tender and sublime Bard has, contrary to the usual fate of Authors,

enriched himself by his talents of one kind or another. He has purchased an

Estate in a beautiful spot on the Spey, twelve miles below this, where he

keeps a Hall of Shells, and indeed lives with the state and hospitality of a

Chieftain,'—not like

‘A meagre muse-rid mope, adust and thin,

In a loose night-gown of his own dun skin.’

Apropos: he is a full, handsome man, and distinguished among his countrymen

by the epithet of ‘ Fair James.’ He is now engaged in building a house which

is to cost ^4000. Only think how this must dazzle people accustomed to look

on glass windows as luxury, and on floors as convenient but by no means

necessary appendages to a building. I am the only lady in the country that

has not tasted of his Shells, or been warmed by the flame of his oaks. Judge

how domestic I am with my twins.”

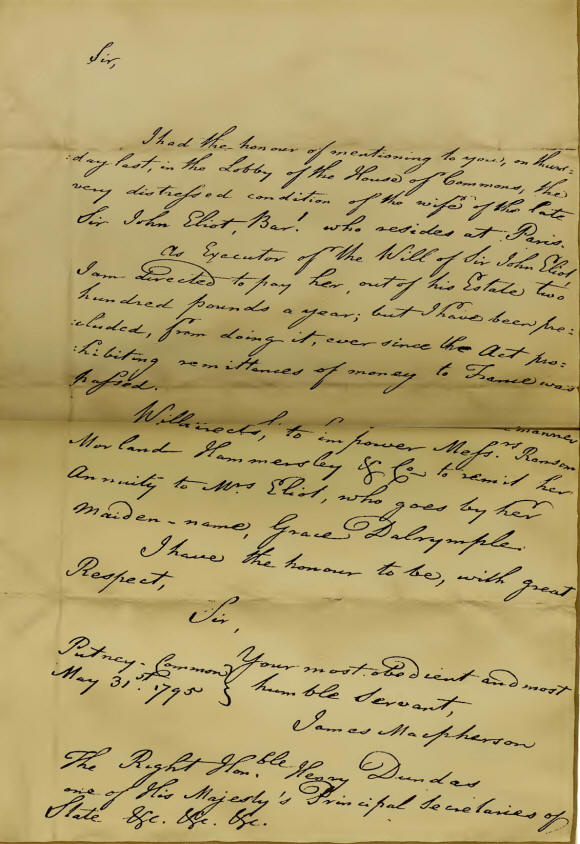

As indicative of Macpherson’s kindly and considerate disposition, a letter

written by him in 1795—a few months before his death—is here reproduced in

facsimile.

Here are some very pleasing reminiscences of Macpherson, about this period

of his life, given by Dr Carruthers :—

“We were once,” says Dr Carruthers, “ferried over the Spey by an old

greyheaded Celt—a capital head for Caravaggio—who had fifty years before

done the same duty for Macpherson. The poet was a great man from London and

the Court, bedizened with rings, gold seals, and furs; but he looked with a

moistened eye on the turf schoolhouse in which he had once taught English,

and on the hills on which he had run in his youth. They were then his own

property, and he told the ferryman, with strong emotion, and no doubt with

Highland pride, that he would make every poor Highlander on his estate a

comfortable and a happy man ! We have always thought more of Macpherson

since.

“An act of generosity is recorded of him connected with the Chief of his

Clan, Cluny Macpherson. Cluny had been 'out in the forty-five,’ and his

estate was confiscated. When Macpherson rose into favour with the

Government, he exerted himself to have the property restored. It was offered

to himself! He had the virtue to decline the offer; and at length he

succeeded in placing it again in the hands of the rightful owner.

“To the poor around

Belleville he seems uniformly to have been kind and generous. For several

years before his death he had been in the habit of spending a few weeks

during summer on his Highland property. He built his house not by contract,

but by native workmen, whom he paid liberally on day’s wages; and he was the

first person in Badenoch who gave is. a-day to agricultural labourers, who

had previously received only 8d. and 9d. Scores of them were employed on his

grounds and in forming his embankments. His gay and social habits drew

around him much company. After a forenoon’s writing he used to mount his

horse, sally out, and bring home with him ‘ troops of friends ’ from both

sides of the Spey. Then with wine and jest—and no man was more various and

fascinating in society —the festivities were prolonged far into the deep

dark night of the mountains. A fatal close soon came to his prosperous

career. He had been late in visiting the Highlands in the summer of 1795,

and, feeling unwell, he resolved on remaining through the winter.” |