|

“Weep, thou father of Morar!

Weep; but thy son heareth thee not. Deep is the sleep of the dead; low their

pillow of dust. No more shall he hear thy voice, no more awake at thy call.

When shall it be morn in the grave, to bid the slumberer awake? Farewell,

thou bravest of men.” — Ossian’s Lament at the Tombs of Heroes.

TO voices of heroes long

vanished,

Ye live, overcoming the tomb,

While lingers the music of Ossian

Rund hills where the heather doth bloom.”

—Nicolson.

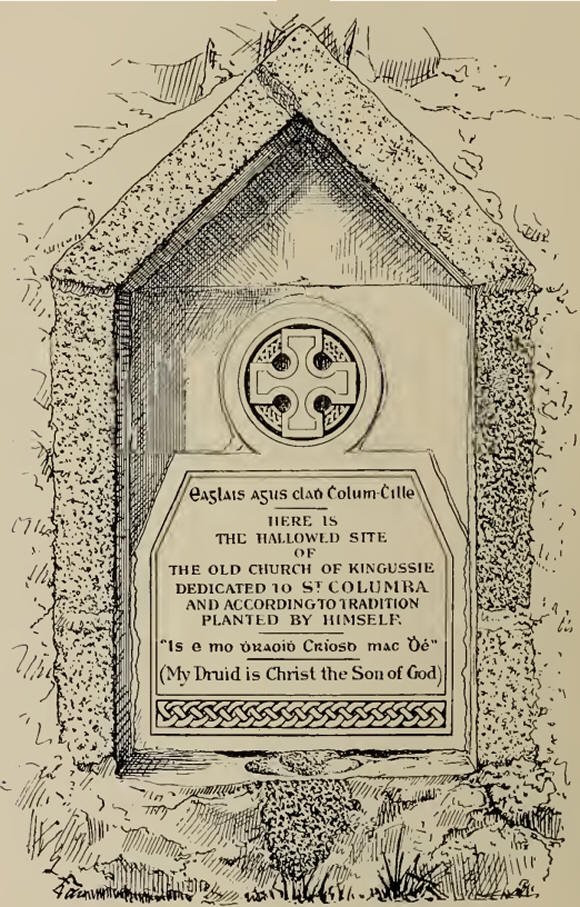

IN giving a few gleanings and

traditions gathered from various sources regarding the old church and

churchyard of Kingussie, it may not be out of place, by way of introduction,

to give a glimpse or two of the great missionary saint and Highland apostle,

by whom, according to popular tradition, the church was planted, and to whom

it was dedicated.

In the very interesting Life of St Columba by the elder Dr Norman

Macleod—the large-hearted, Highlander-loving minister for so many years of

St Columba’s Gaelic Church in Glasgow—it is related that Columba, with

twelve of his favourite disciples, left Ireland 563 a.d. in a little curach

built of wicker-work covered with hide, arriving on Whitsun Eve in that year

at the “ lonely, beautiful, and soft-aired Iona,” which subsequently

remained his home down to the date of his death in 597 a.d. The

Highlands—indeed the whole country north of the Forth and Clyde —were at

that time, we are told, like a vast wilderness, without way or road through

the thick dark woods-—the hills extensive and full of wild beasts. But in

spite of all this Columba persevered. During four-and-thirty years he never

rested nor wearied in the work of founding churches and spreading the Gospel

of Christ. In his day he established three hundred churches, besides

founding one hundred monasteries ; and as he penetrated in the course of his

mission so far north as Inverness, the probability undoubtedly is that the

old church of Kingussie was one of the number thus planted by him.

No traces remain of the buildings which he thus raised, but some particulars

of their general character have come down to us. “ There was an earthen

rampart which enclosed all the settlement. There was a mill-stream, a kiln,

a barn, a refectory. The church, with its sacristy, was of oak. The cells of

the brethren were surrounded by walls of clay held together by wattles.

Columba had his special cell in which he wrote and read; two brethren

stationed at the door waited his orders. He slept on the bare ground, with a

stone for his pillow. The members of the community were bound by solemn

vows. . . . Their dress was a white tunic, over which was worn a rough

mantle and hood of wool left its natural colour. They were shod with

sandals, which they took off at meals. Their food was simple, consisting

commonly of barley-bread, milk, fish, and eggs.” According to the evidence

of Adamnan, his successor and biographer, the foundation of Columba’s

preaching, and his great instrument in the conversion of the rude Highland

people of that early time, was the Word of God. “No fact,” says Dr MacGregor

of St Cuthbert’s, “could be more significant or prophetic. It was the pure

unadulterated religion of Jesus that was first offered to our forefathers,

and broke in upon the gloom of our ancient forests. The first strong

foundations of the Scottish Church were laid broad and deep, where they rest

to-day, on the solid rock of Scripture. It was with the Book that Columba

fought and won the battle with Paganism, Knox the battle with Popery,

Melville the first battle of Presbytery with Episcopacy —the three great

struggles which shaped the form and determined the fortunes of the Scottish

Church.”

The picture of the closing scene in the life of St Columba on 9th June 597

a.d., as given by Dr Boyd of St Andrews—the well-known “A. K. H. B.”—in his

eloquent lecture on “Early Christian Scotland,” is so beautiful and touching

that I cannot refrain from quoting it:—

“On Sunday, June 2, he was celebrating the Communion as usual, when the face

of the venerable man, as his eyes were raised to heaven, suddenly appeared

suffused with a ruddy glow. He had seen an angel hovering above the church,

and blessing it: an angel sent to bear away his soul. Columba knew that the

next Saturday was to be his last. The day came, and along with his

attendant, Diormit, he went to bless the barn. He blest it, and two heaps of

winnowed corn in it; saying thankfully that he rejoiced for his beloved

monks, for that, if he were obliged to depart from them, they would have

provision enough for the year. His attendant said, ‘ This year, at this

time, father, thou often vexest us, by so frequently making mention of thy

leaving us.’ For, like humbler folk drawing near to the great change, St

Columba could not but allude to it, more or less directly. Then, having

bound his attendant not to reveal to any before he should die what he now

said, he went on to speak more freely of his departure. ‘ This day,’ he

said, ‘ in the Holy Scriptures is called the Sabbath, which means Rest. And

this day is indeed a Sabbath to me, for it is the last day of my present

laborious life, and on it I rest after the fatigues of my labours; and this

night at midnight, which commenceth the solemn Lord’s Day, I shall go the

way of our fathers. For already my Lord Jesus Christ deigneth to invite me;

and to Him in the middle of this night I shall depart at His invitation. For

so it hath been revealed to me by the Lord Himself.’

“Diormit wept bitterly; and they two returned towards the monastery. Halfway

the aged saint sat down to rest at a spot afterwards marked with a cross;

and while here, a white pack-horse, that used to carry the milk-vessels from

the cowshed to the monastery, came to the saint, and laying its head on his

breast, began to shed human tears of distress. The good man, we are told,

blest his humble fellow-creature, and bade it farewell. Then ascending the

hill hard by he looked upon the monastery, and holding up both his hands,

breathed his last benediction upon the place he had ruled so well;

prophesying that Iona should be held in honour far and near. He went down to

his little hut, and pushed on at his task of transcribing the Psalter. The

last lines he wrote are very familiar in those of our churches where God’s

praise has its proper place; they contain the words of the beautiful anthem

which begins, ‘O taste and see how gracious the Lord is.’ He finished the

page; he wrote the words with which the anthem ends, ‘ They that seek the

Lord shall want no manner of thing that is good’; and laying down his pen

for the last time, he said, ‘Here at the end of the page I must stop; let

Baithene write what comes after.’

“Having written the words, he went into the church to the last service of

Saturday evening. When this was over, he returned to his chamber and lay

down on his bed. It was a bare flag, and his pillow was a stone, which was

afterwards set up beside his grave. Lying here he gave his last counsels to

his brethren, but only Diormit heard him. ‘These, O my children, are the

last words I say to you: that ye be at peace, and have unfeigned charity

among yourselves; and if, then, you follow the example of the holy fathers,

God, the Comforter of the good, will be your Helper: and I, abiding with

Him, will intercede for you, and He will not only give you sufficient to

supply the wants of this present life, but will also bestow on you the good

and eternal rewards which are laid up for those that keep His commandments.’

The hour of his departure drew near, and the saint was silent; but when the

bell rang at midnight, and the Lord’s Day began, he rose hastily and hurried

into the church faster than any could follow him. He entered alone, and

knelt before the altar. His attendant following, saw the whole church blaze

with a heavenly light; others of the brethren saw it also ; but as they

entered the light vanished, and the church was dark. When lights were

brought, the saint was lying before the altar : he was departing. The

brethren burst into lamentations. Columba could not speak; but he looked

eagerly to right and left with a countenance of wonderful joy and gladness,

seeing doubtless the shining ones that had come to bear him away. As well as

he was able he moved his right hand in blessing on his brethren, and thus

blessing them the wearied saint passed to his rest: St Columba was gone from

Iona. . . . There is but one account of his wonderful voice—wonderful for

power and sweetness. In church it did not sound louder than other voices;

but it could be heard perfectly a mile away. Diormit heard its last words j

the beautiful voice could not more worthily have ended its occupation. With

kindly thought of those he was leaving, with earnest care for them, with

simple promise to help them if he could where he was going, it was fit that

good St Columba should die.”

To quote the beautiful lines of the late Principal Shairp of St Andrews

—another warm-hearted friend, by the way, of the Highlands and Highland

people:—

“Centuries gone the saint from Erin

Hither came on Christ’s behest,

Taught and toiled, and when was ended

Life’s long labour, here found rest;

And all ages since have followed

To the ground his grave hath blessed.”

Little or no reliable information regarding the old church of Kingussie

earlier than the twelfth century has come down to us. About the middle of

that century Muriach, the historical parson of Kingussie, on the death of

his brother without issue, became head of his family, and succeeded to the

chiefship of Clan Chattan. Of Muriach and his five sons the following

account is given in ‘ Douglas’s Baronage of Scotland’:—

"Muriach or Murdoch, who being born a younger brother, was bred to the

Church, and was parson of Kingussie, then a large and honourable benefice;

but, upon the death of his elder brother without issue, he became head of

his family, and captain of the Clan Chattan.

“He thereupon obtained a dispensation from the Pope, anno 1173, and married

a daughter of the Thane of Calder, by whom he had five sons.

“1. Gillicattan, his heir.

“2. Eivan or Eugine Baan, of whom the present Duncan Macpherson, now of

Clunie, Esq., is lineally descended, as will be shown hereafter.

“3. Neill Cromb, so called from his stooping and round shoulders. He had a

rare mechanical genius, applied himself to the business of a smith, and made

and contrived several utensils of iron, of very curious workmanship ; is

said to have taken his surname from his trade, and was progenitor of all the

Smiths in Scotland.

“4. Ferquhard Gilliriach, or the Swift, of whom the Macgillivrays of Drum-naglash

in Inverness-shire, and those of Pennygoit in the Isle of Mull, &c., &c.,

are descended.

“5. David Dow, or the Black, from his swarthy complexion. Of him the old

Davidsons of Invernahaven, &c., &c., are said to be descended.

“Muriach died in the end of the reign of King William the Lion, and was

succeeded by his eldest son.”

Surnames about this time having become hereditary, Macpherson— that is, “Son

of the Parson”—became the distinguishing Clan appellation of the descendants

of Muriach’s second son, who, in consequence of the death of the eldest son

without issue, became the senior or principal branch of Muriach’s posterity.

Were the famous parson to appear again in the flesh, he would doubtless be

lost in utter amazement to find that the descendants of his third son, Neill

Cromb, had “multiplied and replenished the earth ” to such an extent that

all of the name of Smith in Scotland alone might now be reckoned almost as

the sands on the seashore in multitude.

A charter by William the Lion, of date 25th August 1203, concerning the

church of Kingussie, is in the following terms:—

“W., by the Grace of God, King of the Scots, to all good men throughout his

land greeting: Know that I have granted, and by this Charter confirmed, that

presentation which Gilbert de Kathern made to Bricius, Bishop of Moray, of

the Church of Kynguscy, with the Chapel of Benchory and all the other rights

appertaining thereto, to be held as liberally, peacefully, in munificence

and honour, as the Charter of the aforesaid Bricius testifies.”

A concession of Bishop Andrew de Moravia (who succeeded Bishop Bricius)

anent the prebends of Kingusy and Inche, dated in 1226, is in these terms :—

“In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, Amen : I, Andrew, Bishop

of Moray, with the consent of the Chapter of Moray, in order to amplify

divine worship in our Cathedral Church—to wit, the Church of the Holy

Trinity at Elgin —appoint two prebends, and these I assign to the same

Church for ever, lawfully to be held and possessed as prebends or

canonries—one, namely, of the Churches of Kingusy and Inche with their

manses; the other of the Churches of Croyn and Lunyn with their manses. And

I will that whoever for the time being is my vicar in the Cathedral Church

should have these, and that he become the Canon of the same Church, to make

his abode in the same as my vicar,” &c.

Bishop Andrew “confirmed the gift of Bishop Bricius for eight canonries, and

to them he added the kirks of Rhynie, Dunbenan, Kynor, Inverkethny, Elethin

(now Elchies), and Buchary (now Botary), Crom-dale and Advyn, Kingusy and

Inch, Croyn and Lunyn (probably now Croy and Lundichty or Dunlichtie).”

An agreement between the same Bishop and Walter Cumyn, between the years

1224-33, runs as follows:—

“Let all who are likely to see or hear of this writing know that this is the

final peace and agreement made between Andrew, Bishop of Moray, on the one

side, and Walter Cumyn on the other—viz., that the aforesaid Bishop, with

the common consent of all his Chapter, renounced for himself and his

successors for all time, all those things which the bishops of Moray were

wont to receive or exact from the land of Badenoch yearly—viz., 4 marts, 6

pigs, 8 cogs of cheese, and 2^ chalders [of corn], and twenty shillings,

which the same Walter was bound to give to the bishops of Moray, for one

davach of land at Logykenny, and 12 pence, which the same paid for

Inverdrummyn. ... In consideration of which, the same Walter gave and

granted to the bishops of Moray for ever a davach of land in which the

Church of Logykenny is situated, and another davach at the Inch in which is

situated the Church of Inch, and 6 acres of land near the Church of Kingusy,

in which that Church is situated. Moreover, all the bishops of Moray shall

hold in pure and perpetual charity all these lands, with all privileges

justly appertaining to them—in forest and plain, in meadows and pastures, in

moors and marshes, in water-pools and grinding-mills, in wild beasts and

birds, in waters and fishes.”

By an ordination order of Bishop Andrew, between the Chapter of Moray and

the Prebendary of Kinguscy, of date 10th December 1253, it is declared that—

“To all the sons of the Holy Mother Church who may see or hear this writing,

Archibald], by divine permission Bishop of Moray, gives eternal greeting in

the Lord. Since the Chapter of the Church of Moray, on account of divers

causes and matters pertaining to the same Church, has been burdened with

debt, and for as much as, for the apparent advantage of the Church itself,

it has freely granted 10 marks annually to Master Mathew, a writer from the

City of our Lord the Pope —we, being anxious to provide for the alleviation

and security of the same, with the express wish and consent of William of

Elgin, Prebendary of Kinguscy, who has bound himself by oath to observe this

order of ours for himself and his successors, grant and ordain that the

aforesaid Chapter shall acquire and have every year at the feast of St John

the Baptist, during the whole life of the said Master Mathew, 20 marks from

the tithes of the crops of Kinguscy and the Inche, to be received through

the hands of the said William, or whoever is appointed prebendary in the

same prebend, or the agents of the same ; and also that the said William,

and prebendaries of Kinguscy succeeding the same, shall pay every year at

the above feast to the Procurator of the Chapter one mark sterling for

expenses incurred in connection with the sending of the said money to

Berwick.”

In 1380, Alexander Stewart, the notorious Wolf of Badenoch, cited the Bishop

of Moray of the time (Alexander Bur) to appear before him at the Standing

Stones of the Rathe of Easter Kingussie (“apud le standand stanys de le

Rathe de Kyngucy estir”), on the 10th October, to show his titles to the

lands held in the Wolfs lordship of Badenoch—viz., the lands of

Logachnacheny (Laggan), Ardinche (Balnespick, &c.), Kingucy, the lands of

the chapels of Rate and Nachtan, Kyncardyn, and also Gartinengally. The

bishop had protested, at a court held at Inverness, against the citation,

and urged that the said lands were held of the king direct. But the Wolf

held his court of the 10th October, and the bishop standing “extra curiam”—outside

the court, i.e., the Standing Stones— renewed his protest, but to no

purpose. But upon the next day before dinner, and in the great chamber

behind the hall in the castle of Ruthven, the Wolf annulled the proceedings

of the previous day, and gave the rolls of court to the bishop’s notary, who

certified that he put them in a large fire lighted in the said chamber,

which consumed them.2 In 1381 the Wolf formally quits claims on the

above-mentioned church-lands; but in *383 the bishop granted him the wide

domain of Rothiemurchus—

“Ratmorchus—viz., sex davatas terre quas habemus in Strathspe et le Badenach.”

“The Priory of Kingussie in Badenoch,” says Shaw, “was founded by George,

Earl of Huntly, about the year 1490. Of what Order the monks were, or what

were the revenues of the Priory, I have not learned. The Prior’s house and

the Cloysters of the Monks stood near the Church, where some remains of them

are to be seen. The few lands belonging to it were the donation of the

family of Huntley, and at the Reformation were justly reassumed by that

family.” That priory is supposed to have been built on the site of the old

church of St Columba, and the village of Kingussie is said to occupy its

precincts. In course of the improvements recently made in the churchyard a

portion of one of the gables was distinctly traced.

In the ‘Register of Moray’ the name of Gavin Lesly is mentioned as

“Prebendary of Kyngusy” in 1547, that of George Hepburne as prebendary in

1560, and that of Archibald Lyndesay as prebendary in 1567.

Mr Sinton, the esteemed minister of Dores, so well known as a collector of

the old folk-lore and songs of Badenoch, thus relates one of the most

ancient traditions which has survived in Badenoch in connection with St

Columba :—

“St Columba’s Fair, Feill Challiim-Chille, was held at midsummer, and to it

resorted great numbers of people from the surrounding parishes, and some

from distant towns who went to dispose of their wares in exchange for the

produce of the country. Once upon a time the plague or Black Death which

used to ravage Europe broke out among those who were assembled at Feill

Challum-Chille. Now this fair was held partly within the precincts

consecrated to St Callum and partly without, and so it happened that no one

who had the good fortune to be within was affected by the plague, while

among those without the sacred bounds it made terrible havoc. At the

Reformation a plank of bog-fir was fixed into St Columba’s Church from wall

to wall, and so divided the church. In the end which contained the altar the

priest was allowed to officiate, while the Protestant preacher occupied the

farther extremity.”

The example thus shown in such troublous times of the “unfeigned charity” so

touchingly inculcated by the good St Columba with his dying breath more than

a thousand years previously, reflects no little credit upon Badenoch, and it

does not appear that the cause of the Reformation suffered in that wide

district or was retarded in any way in consequence. “The sockets of the

plank,” adds Mr Sinton, “were long pointed out in the remains of the masonry

of the old church.” Unfortunately, when part of the north wall of the

churchyard was repaired nearly thirty years ago, these remains appear to

have been incorporated with the wall and almost entirely obliterated.

Here are some further reminiscences received from the late Mr MacRae, the

Procurator-fiscal at Kirkwall, a worthy and much-respected native of

Badenoch :—

“One of my earliest—indeed I may say my earliest recollection,” says Mr

MacRae, “is connected with this churchyard. I remember one hot summer

Sabbath afternoon—it must, I think, have been in the year 1845—sitting with

my father upon a tombstone in the churchyard listening, along with a crowd

of others, to a minister preaching from a tent. I cannot say who the

minister was, but I was at the time much impressed with his earnestness, and

with what, on reflection, I must now think was a most unusual command of the

Gaelic language and Gaelic idioms. In one of his most earnest and eloquent

periods he and the large congregation listening to him were startled by

seeing the head of a stag looking down over the dyke separating the

churchyard from the hill-road, which was used as a peat road, and which used

to be the short-cut by pedestrians to Inverness. The stag was tossing his

head about, evidently bellicose. The bulk of the congregation were from the

uplands of the parish—Strone, Newtonmore, Glen-banchor, &c.—and they by its

movements recognised the stag as a young stag that the worthy and

much-respected occupants of Ballachroan attempted to domesticate. They were

not in this attempt more successful than others; for the stag’s great

amusement was to watch from the uplands persons passing along the public

road, and then giving them, especially if they were females, a hot chase.

That Sabbath he had, as I subsequently learned, been in the west Kingussie

Moss amusing himself by overturning erections of peat set up to dry. Those

of the congregation who knew his dangerous propensities became very uneasy,

and in consequence the service was interrupted; but some of those present

managed to get him away, after which the service was proceeded with.

“I used to be very often in the churchyard. It had a great attraction for

all the youths in the west end of Kingussie. The ruins of the old church

engrossed our attention next to witnessing funerals. The walls of the church

were, when I first remember them, more perfect than they are at present. The

church consisted of a nave, rectangular, without a chancel. The east and

south walls were almost perfect. The west gable was away. The stones of the

north wall were partially removed, and used for repairing the north dyke of

the churchyard. There were traces of windows in the south wall, but whether

these windows were round, pointed, or square, could not be inferred from the

state of the walls.

“In the remains of the north wall there was—about 2 yards, I should say,

westward from the east gable—an aperture with a circular arch, which

interested us boys at the time very much. It was about 18 inches in length,

12 in height, and 5 in depth. We had many discussions in regard to it, some

of us contending that it was a receptacle for the Bible, others that it was

a canopy for a cross or an image; but it undoubtedly was a piscina where the

consecrated vessels—paten, chalice, &c.—used in celebrating Mass were kept

when not used during the celebration. The piscina is generally in the south

gable, and has a pipe for receiving the water used in cleaning the sacred

vessels. I will be able to show you a perfect piscina in one of the side

chapels of St Magnus Cathedral when you are next here. It was, however, not

unusual in northern or cisalpine churches, especially in those of an early

date, to have the piscina in the north gable without a pipe. You may depend

upon it that the church was of a very early date, probably of the earliest

type of Latin rural church architecture in Scotland. It may have been built

upon the site of an earlier Celtic church. You might probably ascertain this

by directing the workmen you have employed in putting the churchyard in

order to dig about 5 feet inwards from the eastern gable. If they should

find there any remains of the foundations of a cross gable, between the

north and south gables, you may safely conclude that there was a Celtic

church there, and that the Christian religion was taught in Badenoch before

the close of the tenth century.” |