|

Introductory remarks—Reformation era—Prevailing superstition and

credulity—State of Highlands prior to Reformation—Extraordinary incident in

parish of Farr—“Dying testimony” of Alexander Campbell—Knox’s system of

Church discipline—Powers exercised by Church courts—“A cry from

Craigellachie,”.

"TO the southern inhabitants

of Scotland the state of the mountains and of the islands is equally unknown

with that of Borneo or Sumatra; of both they have only heard a little and

guess the rest. They are strangers to the manners, the advantages, and the

wants of the people whose life they would model and whose evils they would

remedy.” So wrote Dr Johnson, the famous lexicographer and pioneer of

Hebridean travellers, fully a century ago; but in view of the Reports of

Royal Commissions, and of the innumerable magazine and newspaper articles

which have appeared of recent years, on the state of the Highlands—religious

as well as social and political—any appropriateness which may have

previously attached to the great southern Don’s hyperbolical estimate of

Lowland ignorance of our mountaineers and islanders is surely in a fair way

of being altogether removed. We have it in Sacred Writ that “in the

multitude of counsellors there is safety,” and their counsels—varied as they

are—will, let us hope, lead to a remedy being provided for the many evils

still rampant among us, and to our beginning to mend ecclesiastically and

otherwise.

Mistier, it has well been said, than our Highland mountains is our early

Highland history. So speedily and almost entirely overcast was the dawn of

the religious day in the Highlands in 1563, that even in the mainland of

Ross-shire it is difficult to fix the Reformation era earlier than the

re-establishment of Presbytery after the days of the tulchan bishops of

James VI. For fully a century later than 1563 the darkness apparently

lingered. In 1656 the Presbytery of Dingwall reported that the people of

Applecross, “among their abominable and heathen practices, were accustomed

to sacrifice bulls at a certaine time upon the 25th of August, which day is

dedicate, as they conceive, to S. Maurie, as they call him.” In 1678 certain

parties in Eilean Mourie, or St Ruffus, in Loch Ewe, were summoned “for

sacrificing in ane heathenish mannar for recovering the health of Cirstane

Mackenzie.” Such, says Shaw, the historian of Moray, was the prevailing

ignorance, that it “was attended with much superstition and credulity.

Heathenish and Romish customs were much practised. Pilgrimages to wells and

chapels were frequent. Apparitions were everywhere talked of and believed.

Particular families were said to be haunted by certain demons, the good or

bad geniuses of these families—such as: On Speyside, the family of

Rothiemurchus, by Bodach an Duin—i.e., ‘the ghost of the Dune’; the Baron of

Kincardine’s family, by Red Hand, or ‘a ghost, one of whose hands was

blood-red’; Gartinbeg, by Bodach - Gartin; Glenlochie, by Brownie;

Tullochgorum, by Maag Moulach—i.e., ‘One with the left hand all over hairy.’

I find in the Synod Records of Moray frequent orders to the Presbyteries of

Aberlaure and Abernethie to inquire into the truth of Maag Monlach’s

appearing; but they could make no discovery, only that one or two men

declared they once saw, in the evening, a young girl whose left hand was all

hairy, and who instantly disappeared. Almost every large common was said to

have a circle of fairies belonging to it. Separate hillocks upon plains were

called Sitheanan—i.e., ‘fairy hills.’ Scarce a shepherd but had seen

apparitions and ghosts. Charms, casting nativities, curing diseases by

enchantments, fortune-telling, were commonly practised, and firmly believed.

As Dr Garth well describes the goddess Fortune—

‘In this still labyrinth around her lye,

Spells, philters, globes, and schemes of palmistry;

A sigil, in this hand, the gipsy bears,

In t’other a prophetic sieve and shears.’

Witches were said to hold their nocturnal meetings in churches, churchyards,

or in lonely places; and to be often transformed into hares, mares, cats; to

ride through the regions of the air, and to travel into distant countries;

to inflict diseases, raise storms and tempests: and for such incredible

feats many were tried, tortured, and burnt. If any one was afflicted with

hysterics, hypochondria, rheumatisms, or the like acute diseases, it was

called witchcraft; and it was sufficient to suspect a woman for witchcraft

if she was poor, old, ignorant, and ugly. These effects of ignorance were so

frequent within my memory, that I have often seen all persons above twelve

years of age solemnly sworn four times in the year that they would practise

no witchcraft, charms, spells, &c. It was likewise believed that ghosts, or

departed souls, often returned to this world, to warn their friends of

approaching danger, to discover murders, to find lost goods, &c. That

children dying unbaptised (called Tarans) wandered in woods and solitudes,

lamenting their hard fate, and were often seen.”

In his remarkable volume, ‘The Days of the Fathers in Ross-shire,’ the late

well-known Dr Kennedy of Dingwall condenses into two or three sentences the

religious state of the Highlands and Islands prior to the Reformation:

“Papacy claimed the whole region as its own, although its dogmas were not

generally known or its rites universally practised. Fearing no competing

religion, the priesthood had been content to rule the people without

attempting to teach them. His ignorance and superstition made the rude

Highlander all the more manageable in the hands of the clergy, and they

therefore carefully kept him a heathen. . . . Savage heathen could

everywhere be found, trained Papists in very few places, when the light of

the Gospel first shone on the north. There was even then quite as much of

what was peculiar to Druidism in the religious opinions and worship of the

people as of any peculiar practices derived from Popery.”

The following extraordinary incident is taken from the MS. of the late Rev.

Lewis Rose, for many years minister of Tain, and the date assigned to it is

about the year 1730: “At that time there was a certain house in the Parish

of Farr, in the north of Sutherland, in which religious meetings were held.

The moderator there was one whom they did not see, but whose presence might

be gathered from his influence. The principal Man at these meetings at

length rose to such a pitch of pious delusion that he imagined himself to be

God the Father, and another Man gave himself out for God the Son, and a

Woman took the honour of being the Holy Ghost. A third Man, who had an only

son, a child, was dubbed Abraham, the Father of the Faithful. This man was

commanded to sacrifice his Isaac, and he was ready to do so at once. The

mother of the child, however, as was natural, felt her bowels yearn over her

Isaac, and went in haste to gather people to rescue him; but when they came

they found the door barred. Forthwith they unroofed the house in order to

save the life of the child, and at this unlooked-for interruption to the

inhuman orgies the whole delusion evaporated, and the meeting dissolved.”

Almost no less remarkable is the “dying testimony” of an Alexander Campbell,

a native of the parish of Kilchattan, in Argyllshire, born in 1751, whose

death occurred so late as in 1829. Campbell is said to have been “the

greatest and most renowned of all ‘the men’ in the district in which he

lived,” and it would appear that many of the people regarded his sayings as

dictated by positive inspiration. The “testimony” extended to forty-five

closely printed pages, and it is stated that some portions of it were too

indelicate to be printed. The following extracts are given in the worthy

man’s own grammar and according to his own system of orthography :—

“I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against those who tolerate all

heretical sects. I also bear testimony against the Church of England for

using their prayer-book, their worship being idolitrous. I bear testimony

against the Popish Erastian patronising ministers of the Church of Scotland.

This is a day of gloominess and of thick darkness. They are blindfolded by

toleration of popery, sectarianism, idolitary, will-worship, &c. I, as a

dying man, leave my testimony from first to last against the reformed

Presbytery; they are false hypocrites, in principles of adherance to the

modern party, who accept of indulgencies, inasmuch as that they are allowed

to apply to unjust judges. It is evident they are not reformed, when they

will not run any hazard to a constitution according to Christ. I leave my

dying testimony against my brother Duncan Campbell, by the flesh, and his

wife Mary Omey, on account of a quarrel between their daughter and my

housekeeper, having summoned her before a justice of the peace, who having

heard the case, did not take any steps against her; I therefore testify

against them for not dropping the matter. There is no agreement between the

children of the flesh and spirit, as Paul said. I leave my testimony as a

dying man against Duncan Clark, in saying that my brother’s cow was not

pushing mine; he was not present and therefore could not maintain it before

judges. And my brother took his son, who was not come to the years, and got

him to declare along with them. They would not allow my housekeeper to have

the same authority in neighbourhood with them, as she was not married, and

that is contrary to the word, Better to be as I am, as Paul said. I, as a

dying man, leave my testimony against the letter-learned men, that are not

taught in the college of Sina and Zion, but in the college of Babylon, 2

Cor. iii. 6, Rom. vii. 6. They wanted to interrupt me by their

letter-learning, and would have me from the holy covenant, Luke i. 72, and

from the everlasting covenant, Isa. xxiv. 5. I, as a dying man, leave my

testimony against King George the third, for tolerating all denominations in

the three kingdoms of Scotland, England, and Ireland, to uncleanness of

popery, and as he himself reigned as a pope in all these three kingdoms. I,

as a dying man, leave my testimony against paying unlawful tributes and

stipend, either in civil or ecclesiastical courts, not according to the word

of God, Confession of Faith, second reformation covenants, &c., if otherwise

they shall receive the mark of the beast, Rev. xiii. 17, in buying and

selling. I leave my testimony against covetous heritors, who oppress the

poor tenants by augmenting the rents, as John M‘Andrew that was in Ardmuddy,

that he fell over a rock, and judgment came upon him and he died, and

Robertson and M'Lachlan, surveyors, that caused lord Bredalbin to augment

the land, and oppress the poor, and grind the face of the poor tenants. I,

as a dying man, leave my testimony against them that lift the dead, Isa.

lvii. 2, and not to lay to resurrection. I leave, as a dying man, my

testimony against playactors and pictures, Numb, xxxiii. 52, Deut. xviii.

10-14, Gal. iv. 10. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against men and

women being conformed to the world, and women having habits and vails,

headsails, as umbrellas. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against

dancing-schools, as it is the works of the flesh. I, as a dying man, leave

my testimony against the low country, as they are not kind to strangers.

Some unawares have entertained angels (Heb. xii. 12). I, as a dying man,

leave my testimony against women that wear Babylonish garments, that are

rigged out with stretched-out necks, tinkling as they go (Isa. iii. 16-24,

&c.) I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against gentlemen; they

altogether break the bonds of the relation of the words of God (Jer. v. 5).

I leave, as a dying man, my testimony against covetous heritors that oppress

the poor, augment the rents, and grind the face of the poor. That is the

very way of poor tenants now, by proprietors and factors, and laws of the

fat lawyers, as the Jews said, we have a law (John xix. 7). NB.—As I could

not pay that excessive rent that was laid on the place I had, I petitioned

Lord Bredalbane, and there was a deliverance given me of a cow’s grass and a

house, the factor Craignour, John Campbell, lawyer at Inverary, would not

give it, taken as an excuse that the hand of Lord Bredalbane was not in the

deliverance, tho’ it was the same when the clerk did it. That I was obliged

to petition him a second time, that his factor, John Campbell, would not

give me what he ordered, as it was not in his own handwriting, but his

clerk’s. That his lordship again gave it under his own handwriting, to give

me the fourth of the place I was in. But John Campbell would not give it me

unless I would get the certificate of the ministers and elders, as he knew

that I would not ask that, as I came out of the church. I, as a dying man,

leave my testimony against John Campbell, factor, for his unrighteousness,

to put me off. I went to a friend, Mr Peter M'Dougall, to see if he would

certify me as a neighbour to the factor. As my housekeeper was of the same

principle of religion of myself, she assisted me not only in the rent but in

other necessary things. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against Peter

M'Dougall, farmer, Luing, in saying in his letter that I was insisting on

him; that I never did, neither did the elders give me a certificate, as I

would not accept from them as elders. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony

against George the third, that assisted the pope and popish kings,

blindfolded by roguery. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against the

volunteers of Banff, for bragging that they stood and learned their exercise

in spite of weather; was not that blasphemous, presumptuous, as well as to

speak in spite of God. And also the ships that keep their course in spite of

weather, that presumptuous sin (Psalm xix. 13). When God might do as he did

to Cora and Abiram, that the ground was opened and swallowed them in a pit.

I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against men of war, that they stood

their courses against the weather. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony

against men and women to be conformed to the world in having dresses,

parasols, vain head-sails, as vain children having plaiding on the top of

sticks to the wind, that women should become bairns. So that men have

whiskers like ruffian soldiers, as wild as Ishmael, not like Christians as

Jacob, smooth. I, as a dying man, leave my testimony against Quakers,

Tabernacle-folk, Haldians, Independents, Anabaptists, Antiburghers,

Burghers, Chappels of Ease, Relief, Roman Catholics, Socenians, Prelacy,

Armenians, Deists, Atheists, Universalists, New Jerusalemites, Unitarians,

Methodists, Bareans, Glassites, and all sectarians, &c., &c. Alexander

Campbell.

Secred.

“It is a marvellous head-stone in the eyes of the builders, the Lord’s doing

(Ps. cxviii. 22, 23). Also it is marvellous to the most that I digged my

grave before I died, as Jacob (Gen. i. 5), and Joseph of Arimathea (Matt,

xxvii. 57-60). Israel could not bury evil men with good men (Chron. xxi.

18-20, Jer. xxii. 17-19). King Isaiah said, Move not the bones of the men of

God (2 Kings xxiii. 17, 18). It is a bed of rest to the righteous (Isa. lvii.

2), and not rest for the wicked (Isa. xlviii. 22), but a prison. And I

protest that none go in my grave after me, if not have the earnest of this

spirit to be a child of God as I am, of election sure (Rom. viii. 15, 16, 2

Peter i. 10), of the same principle of pure presbyterian religion, the

covenanted cause of Christ and Church government: adhering to the Confession

of Faith, second Reformation, purity and power of covenants, and a noble

cloud of witnesses, testify that Jesus Christ is the head king and governor

of the Church, and not mortal man, as the king now is.

Monumental.

“Here lies the corpse of Alexander Campbell, that lived in Achanadder, and

died in the year . Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was, and

the spirit shall return unto God who gave it (Eccl. xii. 7). The earth is

the Lord’s, and not popish earth, nor popish prelates, nor popish Erastians

either, this burial-place. I testify that the earth is the Lord’s (1 Cor. x.

26, Ps. xxiv. 1). Also I testify against the heneous sin of doctors and men

for lifting the dead out of their graves before the resurrection (Isa. lvii.

2). Some men’s sins go to judgment before them, and some after them (1 Tim.

v. 24). O God, hasten the time when popish monuments be destroyed (Deut.

vii. 5), and hasten the time when the Covenants be renewed (Gen. xxxv. 2).

Away with strange Gods and garments.”

In these times of unceasing ecclesiastical and political controversies,

giving rise to such unrest in our everyday life, one not unfrequently hears

long-drawn sighs for the “good old times,” to which no particular epoch has

yet been positively assigned. Amid the microscopical distinctions so

unhappily prevailing in our Presbyterian Churches, and the wranglings and

strife of rival factions, “the spirit of love and of a sound mind”—to use

the words of the large-hearted Christian leader taken from us a few years

ago—“ is often drowned in the uproar of ecclesiastical passion.” It would, I

believe, be productive of the most beneficial results in our religious as

well as in our political life if, combined with the “sweet reasonableness”

and large tolerance of spirit which characterised Principal Tulloch, we had

more of such plain honest speaking as that of the great reformer, John Knox,

who learned, as he himself says, “to call wickedness by its own terms—a fig

a fig, a spade a spade.” But the so-called “march of civilisation” has

changed the whole current of our social and religious life, and affected the

spirit of the age to such an extent that it may be reasonably doubted

whether the most orthodox and constitutional Presbyterian in the Highlands

would now submit to the administration of discipline to which in days gone

by, without respect of persons, the kirk-sessions of Badenoch in the Central

Highlands so rigorously subjected the wandering sheep of their flocks.

Knox’s system of Church discipline has been described as a theocracy of such

an almost perfect character, that under it the kirk-sessions of the Church

looked after the life and conduct of their parishioners so carefully that in

1650 Kirkton the historian was able to say, “No scandalous person could

live, no scandal could be concealed in all Scotland, so strict a

correspondence was there between the ministers and their congregations.” The

old church annals of Badenoch contain in this respect abundant evidence of

the extent to which the ministers and elders of bygone times in the

Highlands acted as ecclesiastical detectives in the way of discovering and

discouraging “the works of darkness,” and the gleanings which follow give

some indication of the remarkable powers exercised for such a long period by

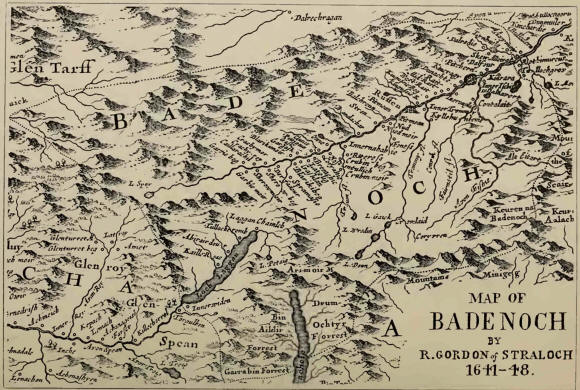

the courts of the Church. These gleanings have been extracted mainly from

the old kirk-session records of the parishes of Kingussie, Alvie, and Laggan,

comprising the whole of the extensive district distinguished by the general

appellation of Badenoch — so long held and despotically ruled by the once

powerful family of the Comyns — extending from Corryarrick on the west to

Craigellachie, near Aviemore, on the east—a distance of about forty-five

miles.

As descriptive of the journey of “the iron horse” northwards from Perth, and

of the changes of Time in “the old Highlands,” let me quote the graphic

lines of the late Principal Shairp of St Andrews, composed after travelling

to Inverness for the first time on the newly opened Highland Railway in

1864, under the title of “A Cry from Craigellachie ”:—

“Land of bens and glens and corries,

Headlong rivers, ocean floods!

Have we lived to see this outrage

On your haughty solitudes?

Yea! there burst invaders stronger

On the mountain-barriered land

Than the Ironsides of Cromwell,

Or the bloody Cumberland.

Spanning Tay, and curbing Tummel,

Hewing with rude mattocks down

Killiecrankie’s birchen chasm;

What reck they of old renown?

Cherished names! how disenchanted!

Hark the railway porter roar—

‘Ho! Blair Athole! Dalna-spidal!

Ho! Dalwhinnie! Aviemore!’

Garry, cribbed with mound and rampart,

Up his chafing bed we sweep;

Scare from his lone lochan-cradle

The charmed immemorial sleep.

Grisly, storm-resounding Badenoch,

With grey boulders scattered o’er,

And cairns of forgotten battles,

Is a wilderness no more.

Ha! we start the ancient stillness,

Swinging down the long incline

Over Spey, by Rothiemurchus’

Forests of primeval pine.

‘Boar of Badenoch,’ ‘Sow of Athole,’

Hill by hill behind me cast,

Rock and craig and moorland reeling,

Scarce Craig-Ellachie stands fast.

Dark Glen More and cloven Glen Feshie,

Loud along these desolate tracts

Hear the shrieking whistle louder

Than their headlong cataracts.

On, still on—let drear Culloden

For clan-slogans hear the scream—

Shake, ye woods by Beauly river;

Start, thou beauty-haunted Dhruim.

Northward still the iron horses!

Naught may stay their destined path

Till they snort by Pentland surges,

Stun the cliffs of far Cape Wrath.

Must then pass, quite disappearing

From their glens, the ancient Gael?

In and in must Saxon wriggle,

Southern, cockney, more prevail ?

Clans long gone, and pibrochs going,

Shall the patriarchal tongue

From the mountains fade for ever,

With its names and memories hung?

Ah! you say, it little recketh;

Let the ancient manners go:

Heaven will work, through their destroying,

Some end greater than you know.

Be it so, but will Invention,

With her smooth mechanic arts,

Bid arise the old Highland warriors,

Beat again warm Highland hearts?

Nay ! whate’er of good they herald,

Whereso’ comes that hideous roar,

The old charm is disenchanted,

The old Highlands are no more.

Yet, I know there lie all lonely,

Still to feed thought’s loftiest mood,

Countless glens undesecrated,

Many an awful solitude.

Many a burn, in unknown corries,

Down dark rocks the white foam flings,

Fringed with ruddy-berried rowans,

Fed from everlasting springs.

Still there sleep unnumbered lochans

Far away ’mid deserts dumb,

Where no human roar yet travels,

Never tourist’s foot hath come.

Many a scour, like bald sea-eagle,

Scalped all white with boulder piles,

Stands against the sunset eyeing

Ocean and the outmost Isles.

If e’en these should fail, I’ll get me

To some rock roared round by seas:

There to drink calm Nature’s freedom

Till they bridge the Hebrides.”

When the Shaws were dispossessed of their family estate the Bodach sang

these lines of lamentation:—

"Ho ro! tlieid sinn’s a’ chiomachas,

Theid sinn a fonn’s a odhaichean

’S ged thug iad uainn ar diithchas

Bidh ar diiil ri cathair na firinn ; ”

which have been freely translated : —

“Ho! Ro! as exiles we go,

From our lands and strongholds, away, away;

But we trust, though out-thrust

By an earthly foe,

To reach the City that lasts for aye,

The City of Peace—for aye, for aye.”

According to the family legend, the Bodach continues to guard the graves and

protect the memorial-stones at Rothiemurchus of the old barons.”—Vide

Roger’s Social Life in Scotland, 1886, iii. 342.

|