|

BY a gradation of

ancient sea beaches which can be traced along the Clyde valley in

the vicinity of Glasgow, the occurrence of successive upheavals of

the land is fully established, and it is obvious that during some

part of the remote period immediately preceding the last of these

elevations the estuary of the Clyde at Glasgow was several miles

wide, covering not only the lower districts of the city but

extending to the base of the Cathcart and Cathkin Hills, and

probably receiving the waters of the river not far from Bothwell.

That this district was then inhabited by man seems to be placed

beyond reasonable doubt by the discovery of canoes in the Trongate

and other localities far above the present level of the river, but

all of them covered by strata of transported sand and gravel.

One canoe was

unearthed in 1780, when excavations were being made for the

foundation of St. Enoch's Church; another was found at the Cross,

when similar preparations were in progress for the erection of the

Tontine buildings; one was got in Stockwell Street, near the present

railway crossing ; and another was dug up on the slope of the

Drygate. All these canoes were formed of single oak trees roughly

scooped out, fire having been employed to burn out the interior, and

were altogether of the most primitive kind of construction, 1 a

description which likewise applies to a number of other canoes that

were found on the lands of Springfield and Clydehaugh on the south

side of the Clyde. These latter canoes, discovered during operations

for the widening of the harbour between 1847 and 1849, seem to have

been deposited at a much later period than those found in higher

ground. No change in the relative positions of land and sea had

apparently taken place between the time when they were swamped or

settled down in the channel of the river till they were again

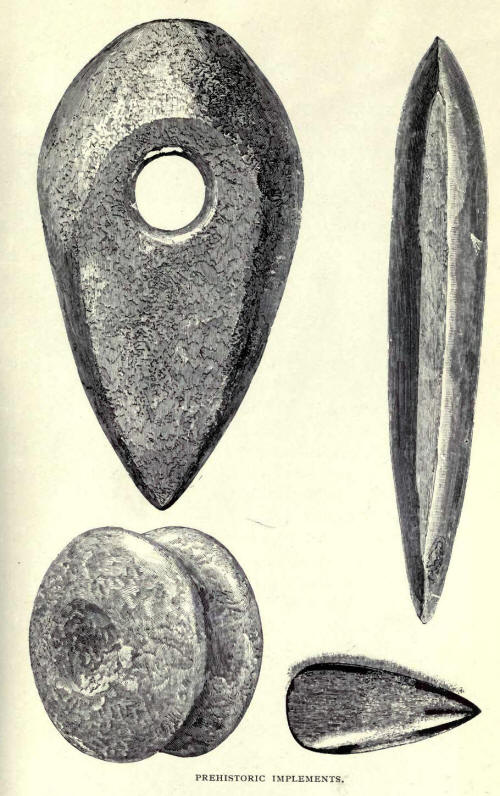

exposed to the light of day. The St. Enoch's Square canoe was 24

feet below the surface, and there was found within it a polished

stone hatchet or celt, one of the instruments which may have been

used in its construction, though it seems as much adapted for war as

for any peaceful art.2

During long ages

which succeeded the final settlement of sea and land level, the

Clyde, running through a tract of

1 A fifth canoe,

discovered in 1825 when opening a sewer in London Street, was built

of several pieces of oak, and exhibited unusual evidences of labour

and ingenuity (Daniel Wilson's Prehistoric Annals, p. 35)

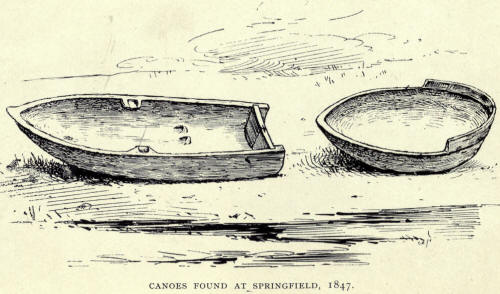

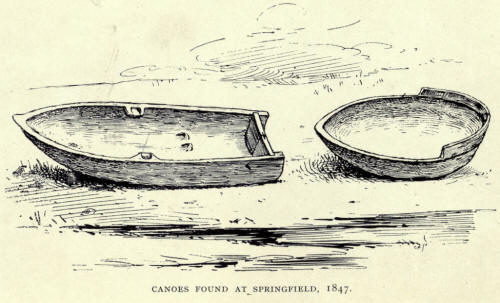

2 Ibid. A sketch of

the celt, given by Mr. Wilson, is here reproduced. All the canoes

discovered in the higher grounds on the north side of the river were

destroyed, and no sketch of their appearance or record of their

dimensions has been preserved. Representations of two of the canoes

found at Clydehaugh, as shown in Scottish History and Life, are here

reproduced : No. 1 measured 14 feet in length, 4 feet 1 inch in

breadth, and 1 foot 11 inches deep; No. 2 was so feet long, 3 feet 2

inches broad, and 1 foot deep.

For fuller

information and interesting speculation on the prehistoric subjects

alluded to in the text reference may be made to Ancient Sea Margins,

by Dr. R. Chambers, pp. 203-9; Daniel Wilson's Prehistoric Annals,

pp. 3I-37; Macgeorge's Old Glasgow (i88o), pp. 248-62; John

Buchanan's narrative in Glasgow : Past and Present (1856), iii. pp.

555-79; Transactions of Glasgow Archceological Society, 1st Series,

I. pp. 188-90; II. pp. 525-30. In the last of these Archaeological

Society's papers Mr. J. Dalrymple Duncan gives an account of the

discovery at Point Isle in 1880 of a canoe which crumbled to pieces

in the hands of those who attempted its removal.

country with no

proper river channel, must have been continually changing its

course, and in the tidal area, specially, not only the bed of each

changing channel, but likewise the land on either side would by

silting process be gradually raised. But the bulk of the sediment

would collect wherever the water had its course for the time, and so

soon as the accumulation became higher than the adjoining ground,

the former channel would be deserted and a new one chosen. Many of

these river variations can still be identified, and it is believed

that such a change is sufficient to account for the Springfield

canoes being found seven feet below the natural bed level of the

river and one hundred yards to the southward of its bank, as these

existed before the artificial deepening which was commenced in 1758

and the widening carried through by the Clyde Trustees in 1847. Such

flooding effects and silting process are also regarded as sufficient

to account for the covering by stratified sand of the beautiful

Roman bowl of Samian ware which, in 1876, was discovered in the

Green, about 4½ feet below the surface.

It was not till

comparatively modern times that the river, in its passage through

that part of the valley which is now city territory, permanently

settled into its present course, and even after embankment,

deepening and other artificial operations and appliances were

adopted, the lower lying grounds, such as Glasgow Green and the

Broomielaw area, were subject to ever recurring floods, which kept

them to a large extent in a more or less swampy condition. The havoc

caused to grain crops by such floods would not often be turned to so

providential a purpose as on the occasion when the scornful king's

barns with their stores of wheat were carried away by the river and

deposited on the banks of the Molendinar to feed the brethren of St.

Kentigern's monastery. [St. Kentigern (Scottish Historians), pp. 69,

70.] Nor would many floods be so disastrous as that of 1454,

altogether of the most primitive kind of construction, [A fifth

canoe, discovered in 1825 when opening a sewer in London Street, was

built of several pieces of oak, and exhibited unusual evidences of

labour and ingenuity (Daniel Wilson's Prehistoric Annals, p. 35)] a

description which likewise applies to a number of other canoes that

were found on the lands of Springfield and Clydehaugh on the south

side of the Clyde. These latter canoes, discovered during operations

for the widening of the harbour between 1847 and 1849, seem to have

been deposited at a much later period than those found in higher

ground. No change in the relative positions of land and sea had

apparently taken place between the time when they were swamped or

settled down in the channel of the river till they were again

exposed to the light of day. The St. Enoch's Square canoe was 24

feet below the surface, and there was found within it a polished

stone hatchet or celt, one of the instruments which may have been

used in its construction, though it seems as much adapted for war as

for any peaceful art.

[Ibid. A sketch of

the celt, given by Mr. Wilson, is here reproduced. All the canoes

discovered in the higher grounds on the north side of the river were

destroyed, and no sketch of their appearance or record of their

dimensions has been preserved. Representations of two of the canoes

found at Clydehaugh, as shown in Scottish History and Life, are here

reproduced: No. 1 measured 14 feet in length, 4 feet 1 inch in

breadth, and 1 foot 11 inches deep; No. 2 was 10 feet long, 3 feet 2

inches broad, and 1 foot deep.

For fuller information and interesting

speculation on the prehistoric subjects alluded to in the text

reference may be made to Ancient Sea Margins, by Dr. R. Chambers,

pp. 203-9; Daniel Wilson's Prehistoric Annals, pp. 3I-37;

Macgeorge's Old Glasgow (i88o), pp. 248-62; John Buchanan's

narrative in Glasgow: Past and Present (1856), iii. pp. 555-79;

Transactions of Glasgow Archceological Society, 1st Series, I. pp.

288-90 II. pp. 121-30. In the last of these Archaeological Society's

papers Mr. J. Dalrymple Duncan gives an account of the discovery at

Point Isle in i 880 of a canoe which crumbled to pieces in the hands

of those who attempted its removal. ]

During long ages which succeeded the

final settlement of sea and land level, the Clyde, running through a

tract of

country with no proper river channel,

must have been continually changing its course, and in the tidal

area, specially, not only the bed of each changing channel, but

likewise the land on either side would by silting process be

gradually raised. But the bulk of the sediment would collect

wherever the water had its course for the time, and so soon as the

accumulation became higher than the adjoining ground, the former

channel would be deserted and a new one chosen. Many of these river

variations can still be identified, and it is believed that such a

change is sufficient to account for the Springfield canoes being

found seven feet below the natural bed level of the river and one

hundred yards to the southward of its bank, as these existed before

the artificial deepening which was commenced in 1758 and the

widening carried through by the Clyde Trustees in 1847. Such

flooding effects and silting process are also regarded as sufficient

to account for the covering by stratified sand of the beautiful

Roman bowl of Samian ware which, in 1876, was discovered in the

Green, about 41 feet below the surface.

It was not till comparatively modern

times that the river, in its passage through that part of the valley

which is now city territory, permanently settled into its present

course, and even after embankment, deepening and other artificial

operations and appliances were adopted, the lower lying grounds,

such as Glasgow Green and the Broomielaw area, were subject to ever

recurring floods, which kept them to a large extent in a more or

less swampy condition. The havoc caused to grain crops by such

floods would not often be turned to so providential a purpose as on

the occasion when the scornful king's barns with their stores of

wheat were carried away by the river and deposited on the banks of

the Afolendinar to feed the brethren of St. Kentigern's monastery.

[St. Kentigern (Scottish Historians), pp. 69, 70.] Nor would many

floods be so disastrous as that of 1454, described by one of our

chroniclers as "ane richt greit spait in Clyde, the xxv and xxvj

days of November, the quhilk brocht doun haile houssis, berms and

millis, and put all the town of Govane in ane flote quhill thai sat

on the houssis." [Ane Schort Memoriale of the Scottis Corniklis (Auchinlek

MS.), p.18.]

But apart from such extreme occurrences the floods experienced so

recently as the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as described by

personal observers, were so serious that one may conceive how little

inducement there was for the early inhabitants to plant their

habitations near the river before a way was discovered for keeping

it within reasonable bounds. If, therefore, the banks of the

Molendinar were inhabited by man in these prehistoric times, his

dwellings must have occupied the higher grounds, and it is

significant that in the earliest account we have of the

comparatively modern days of St. Kentigern it is that part of the

city which is referred to. Joceline, the biographer of St. Kentigern,

writing in the twelfth century makes mention of a cemetery which had

been "long before" consecrated by St. Ninian, and this ancient

cemetery was evidently identified as having occupied the site of the

Cathedral and its adjoining burying ground.

Cathures, which Joceline gives as the

former name of Glasgu, is understood to bear the interpretation of a

fort or encampment, and may well have been applied to the site of

those dwellings placed on the higher grounds, between the Molendinar

and Glasgow Burns, and occupied by a primitive community which had

probably grown up and prospered under the protection of some

powerful chief. In later times this district, traversed by an old

Roman road and including the inhabited area bearing the archaic

designation of Ratounraw, was possessed by rentallers who were

subject to a special bailliary jurisdiction of unknown origin. Early

churches were often planted in such places, and there, as a general

rule, is

to be found the nucleus of the village,

the town and the city.

With the coming of St. Kentigern the

real beginning of Glasgow as a city has aways been associated, and

notwithstanding irregularities in progress and the untoward

vicissitudes of the intervening centuries, it may safely be assumed

that by the time we have the benefit of the few fragments of twelfth

century writings which are still extant, inhabited dwellings had

begun to spread over the lower grounds near the margin of the river.

Keeping within the bounds of the two streamlets, the Molendinar on

the east and Glasgow Burn on the west, the banks of the former seem

to have attracted the bulk of the earlier settlers, but rentallers

of croft land lying along the foot of Glasgow Burn are also traced,

and here, according to ancient tradition, were laid the earthly

remains of St. Kentigern's mother on the spot where the chapel

bearing her name was reared. The ruins of St. Tenew's Chapel were

still in evidence till well on in the eighteenth century, and though

the circumstances connected with its foundation must remain in

obscurity, seeing that any accounts we have of St. Mungo's birth and

parentage are mainly legendary fable and that we have little or no

reliable information on his domestic affairs, there seems to be no

inherent improbability in the substantial correctness of the

traditional story. Another chapel, likewise of unknown antiquity,

was planted in the more populous district just referred to, and was

dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

|