|

THE end of the

fifteenth century is regarded as marking the close of the Middle

Ages and the dawn of a new era for modern Europe. The discovery of

America and of a fresh sea route to India enlarged geographical

knowledge and gave promise of immense advance in commercial

enterprise ; and it may be supposed that other countries besides the

leading maritime nations of Spain and Portugal would share to some

extent in the impetus thus given to trading activity. Of the

prosperous condition of Scotland we have a contemporary account

given by Don Pedro de Ayala, the Spanish ambassador to the court of

King James. Writing in 1498 this foreigner reported that the country

had greatly improved during the king's reign, that commerce was much

more considerable than formerly and was continually advancing. There

were three principal articles of export, wool, hides and fish, and

the customs were substantial and on the increase. [Early Travellers,

pp. 42, 43. Ayala says: "The towns and villages are populous. The

houses are good, all built of hewn stone, and provided with

excellent doors, glass windows, and a great number of chimneys. All

the furniture that is used in Italy, Spain, and France, is to be

found in their dwellings. It has not been bought in modern times

only, but inherited from preceding ages." (Ibid. p. 47.)]

About this time, and

for a considerable period afterwards, Dumbarton was the chief port

in the west of Scotland and the most frequented as a naval base. It

was the favourite place of departure and arrival to and from France.

Expeditions to the Isles were organised at Dumbarton, fleets were

fitted out there, and thence they sailed. At the time King James was

making strenuous efforts to create a navy one ship was built at

Leith, another in Brittany and a third at Dumbarton. There are many

other recorded cases of shipbuilding at Dumbarton, and it long

continued to be a harbour for such royal ships as came to the west

coast. [River Clyde, pp. 17, 18; Lord High Treasurer's Accounts,

iii. and iv. In the year 1512 there are several payments out of the

royal treasury for timber and other material used for the building

of a galley at Glasgow, a vessel about which, unluckily, there are

no further particulars (Ibid. iv. P. 290).]

In 1499 Glasgow and

Dumbarton entered into an amicable arrangement for the defence and

maintenance of each other's privileges. In future each of the two

burghs was to have an equal interest in the river Clyde, neither of

them pretending privilege or prerogative over the other. [Glasg.

Chart. ii. pp. 62, 72, 119. In connection with the purchase of wine

from a ship, in 1531, Glasgow had sued Dumbarton in the consistorial

court, and on this ground the latter burgh alleged that the " band "

of 1499 had been broken, but the treasurer of Glasgow protested

against his burgh being prejudiced by the proceedings (Glasg. Prot.

No. rio3). An indenture entered into between the two burghs, in

1590, is on the same lines as the agreement of 1499, and provision

is made for the settlement of disputes by six representatives from

each who were to meet in the burgh of Renfrew (Glasg. Chart. i. pt.

ii. pp. 225-7)] As subsequent records show this judicious

arrangement worked satisfactorily and, subject to various

modifications, it was renewed from time to time.

Several of the

statutes of James IV. deal with the administration of burgh affairs.

[Ancient Laws, ii. pp. 49-57. Magistrates of burghs were required to

have these Acts openly proclaimed within their bounds.] Thus in May,

1491, better observance of the existing Acts relating to weights,

measures and customs was enjoined, directions were given for

expenditure of the common good only for the necessary purposes of

the burgh and on the advice of the town council and deacons of

crafts, and inquiry was to be made regarding such expenditure in the

yearly circuits of the great chamberlain. To avoid undue alienation

of burgh property, lands, fishings, mills and all yearly revenues

were not to be leased for a longer period than three years at a

time.

To secure the loyalty

of the burgesses both to the nation and to their own rulers it was,

by renewal of a similar Act passed in 1457, [Ancient Laws, ii, p.

29.] ordained that no one dwelling in the burgh should enter into

leagues or manrent bonds with any landward person in any risings or

convocations, but that every one should obey the king or the burgh

authorities in the defence of the realm and for the advantage of the

burgh. In the words of the statute the inhabitants were not to "ride

na rout in fere of were [Not to assemble and march in warlike

array.] with na man bot with the king or with his officiaris or with

the lord of the burgh thai dwell in, or with his officiaris."

Practices introduced

and dues exacted by craftsmen, with regulations passed by deacons of

crafts, had the effect of unduly raising prices and interfering with

the completion of work, and in June, 1493, some interesting statutes

were passed to remedy such evils. In June, 1496, magistrates of

burghs were instructed to fix the prices and quality of victuals,

bread and ale, but this maybe regarded more as a parliamentary

sanction of existing practice than as the introduction of a new

system, because from the earliest times of which their proceedings

are extant town councils seem to have exercised control in that

direction.

An Act passed in

March, 1503, providing that all officers, provosts, bailies and

others having jurisdiction within burgh should be changed yearly,

and that none should hold office except those who "usis merchandice"

within the burgh, may have been strictly observed in Glasgow, except

in the case of the provost whose office, as formerly, seems to have

been regarded as an appendage to the bailieship of the regality. [Antea,

p. 210.]

Membership in the

community of a royal burgh, termed burgesship, originally implied

the possession of real property within the burgh, with the privilege

of sharing in its trade, responsibility for the administration of

its affairs, and liability for the defence of its interests. From an

early period the regulation of admission to the burgess roll was in

the hands of the community, one of the points on which the great

chamberlain inquired on his periodical visitations of a burgh being

"gif the balyeis sell the fredome of the burgh till ony without leif

of the comunite." [Ancient Laws, i. p. 153.] In accordance with the

practice here indicated, it was, in the parliament of 1503, ordained

that the provost and bailies should not make burgesses without the

advice and consent of the great council of the town and that the

profit should go to the common good and be spent on common works. As

representing the community the Town Council fixed the entry money,

which long formed a substantial item in the Common Good assets of

royal burghs. Under numerous legislative enactments burgesses of

royal burghs possessed the exclusive privilege of trade, both home

and foreign, and expenditure in enrolment as a burgess was thus a

remunerative investment. In Glasgow the rights of burgesses are

recognised in the foundation charter of the burgh. "I will and

straitly enjoin," so runs the royal mandate, "that all the burgesses

who shall be resident in the foresaid burgh shall justly have my

firm peace through my whole land; and I straitly forbid any one

unjustly to trouble or molest them or their chattels." [Glasg.

Chart. i. p. 4.] It may safely be assumed that Glasgow burgesses

have all along enjoyed the usual privileges of their class, but on

account of the extant council records not beginning at an earlier

date than 1573 there is little actual evidence on the subject prior

to that date.

On a vacancy in the

chaplainry at the altar of St. Kentigern, founded by Sir Walter

Stewart of Arthurle, on the south side of the nave of the cathedral,

[Glasg. Chart. i. pt. ii. pp. 45-52.] occurring in the year 1505-6,

Sir Bartholomew Blare, chaplain, was inducted, by delivery of the

chalice, missal and ornaments of the altar. It had been provided

that on failure of heirs-male of the founder the patronage was to

belong to the bailies and community, and though it is not recorded

that they nominated the new chaplain they took part in some of the

necessary arrangements. The induction took place on loth February,

1505-6, and two days later Patrick Culquhoune, provost, and two

bailies, in name of the whole community of the city, delivered to

the inducted chaplain the furnishings and ornaments of the altar,

conform to a list which is quoted below as indicating the vast

amount of valuable material which must have been stored in the

cathedral, assuming that each of its many altars was fitted up and

decorated in a somewhat similar manner. ["First, an image of the

Saviour with a pedestal, in a wooden chest, of alabaster; an image

of the glorious Virgin, on a table of alabaster; two large

chandeliers, and two small brass prikkets; two extinguishers for

torches, of tin; two silver phials, one of which wanted 'the strowp';

a chasuble of blue, with the hood, stole, and apparels thereof; a

chasuble of dun-coloured `sathyne,' without the hood, stole, and

apparels; a chasuble of burd alexander; two white albs, with an old

alb; a missal, with a wooden boss of overlaid work; two curtains of

taffety; six coverings for the altar of linen cloth; two amices; a

hanging of arras cloth, suspended at a pillar before the altar; a

frontal of black velvet, with a frontal hanging to the ground joined

to it of arras work, also an arras frontal with a hanging front of

worsted reaching to the ground ; two cushions of blue and red

velvet; a stole with a fillet of Liege cloth of gold—'the luke'; two

apparels of red velvet upon the tail, with an apparel of green burd

alexander upon the sleeve of an alb; an apparel upon an amice of

green burd alexander; a large hanging chandelier before the altar."

Burd alexander was a kind of cloth manufactured at Alexandria and

other towns in Egypt.] The chaplain accepted the custody of the

articles delivered to him, but protested for the replacement of

those which were wanting, when they happened to be restored to the

altar. [Diocesan Reg. Prot. Nos. 148-9.]

About four months

later Andrew Stewart, son of the founder of the chaplainry, and then

archdeacon of Candida Casa, founded another chaplainry at St.

Kentigern's altar, endowing it with four tenements on the west side

of the High Street. [Reg. Episc. No. 485. Provision was made for the

tenements being kept in repair; and on the day of the founder's obit

the chaplain was instructed to bestow sixpence each on forty poor

fathers and mothers of families, the procurators who distributed the

money receiving 3s. for their trouble, and the priest who served the

original chaplainry was also to get 3s.] Some little time must have

been occupied in preliminary details, but on 17th November, 1507,

the founder conferred the new chaplainry on Sir James Houstoun,

deacon, who latterly came to be well known as subdean and founder of

the Collegiate Church of St. Mary and St. Anne in the city. In the

instrument recording the appointment the founder takes the

opportunity of narrating that the endowments of the chaplainry

consisted of goods bestowed by God and collected by his own industry

and labour. [Dioc. Reg. Prot. No. 281.]

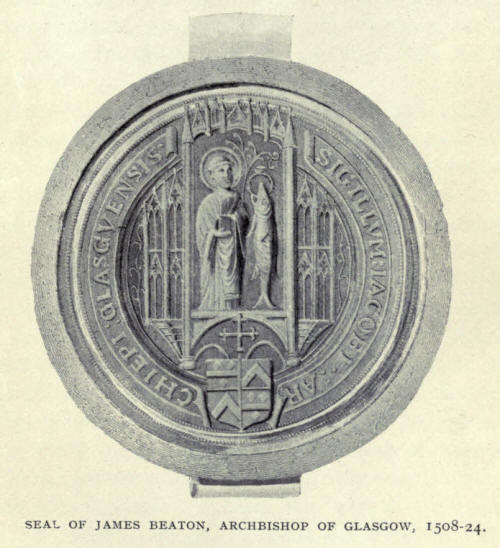

Archbishop Blacader

died in the end of July, 1508, while on a voyage in pilgrimage to

the Holy Land. News of his reported demise probably reached Scotland

by October, as James Beaton, then bishop of Galloway, [Archbishop

Beaton was the sixth son of John Beaton of Balfour in Fife, his

mother being INIarjory, daughter of Sir David Boswell of Balmuto.

Bethune, Betone and Betoun, are varying forms which this name takes

in sixteenth century MSS. "Beaton" is adopted here in conformity

with modern usage.] was at the king's desire chosen by the chapter

of Glasgow as his successor, on 9th November, but under reservation

of the right and possession of the former archbishop, "if he still

survived." All doubt as to the actual vacancy having been removed,

the chapter, on 8th April, 1509, complied with letters sent by Pope

Julius and received the new archbishop as the father and shepherd of

their souls. Similarly cordial welcome was given by the university

and clergy and by the bailies in name of the citizens and people of

Glasgow, and on 18th April the archbishop himself, sitting in

judgment in the chapter house, "for restoring rights and hearing

causes," declared that he was prepared to render justice to those

who desired to prosecute any ecclesiastical persons of his diocese,

repledged from the court of justiciary to the jurisdiction of

ecclesiastical liberty. [Dioc. Reg. Prot. Nos. 288-90, 358-60;

Dowden's Bishops, pp. 334 40.]

The jurisdiction here

referred to was that exercised in the court of the archbishop's

Official, otherwise called the commissary or consistory court. Four

months later the archbishop granted a commission to Lord Gray, the

king's justiciar, authorising him to hold a court of his (the

archbishop's) regality of Glasgow, within the tolbooth of Edinburgh,

for the trial of Alexander Likprivik and his accomplices for the

murder of George Hamilton within the regality and city of Glasgow,

the accomplices being also charged with other crimes. The

commission, which was presented by John Stewart of Minto, bailie of

the regality and provost of the city, was accepted by Lord Gray and,

while the reason for holding the trial in Edinburgh is not stated,

the archbishop, who was present, took the precaution of protesting

that this should not be to the prejudice of the regality of Glasgow.

[Reg. Episc. No. 488. The trial ended in the conviction and capital

sentence of Alexander Lekprevik, but he had a royal pardon.

(Pitcairn's Criminal Trials, pp. 62*; 110*.)]

The jurisdiction

exercised by the Official throughout the diocese was so

comprehensive as to leave few subjects beyond its range, but the

bailies of the burgh maintained that none of the citizens ought to

summon another citizen before a spiritual judge ordinary respecting

a matter which could be competently decided before the bailies in

the court-house of the burgh. A citizen who was fined in the burgh

court for transgressing this rule appealed to the court of the

Official, and some of the proceedings, including the decision of the

burgh court, are recorded in documents dated in December and

January, 1510-z. While the magistrates, through their provost, the

Earl of Lennox, appear to have adhered to their position, it was

declared that the magistrates and citizens would not do anything

against the liberty and jurisdiction of Holy Mother Church. [Dioc.

Reg. Prot. Nos. 498, 503-4. One of the points of inquiry to be made

by the great chamberlain on his circuit of the burghs was "gif ony

drawis his nychtbouris in the christiane court fra the secular."

(Ancient Laws, i. pp. 152-3.)]

Alexander Stewart, a

son of the king, had been provided to the archbishopric of St.

Andrews, in 1504, while he was yet a child of about eleven years of

age, the actual administration of affairs being entrusted to

churchmen of mature experience. On the occasion of a visit to

Glasgow by the young archbishop, when in his seventeenth or

eighteenth year, the feeling of independence and anxiety for the

maintenance of their privileges was manifested by the clergy of

Glasgow diocese, as represented by the cathedral chapter. Hearing

that the archbishop, who was likewise primate of Scotland and papal

legate, was approaching the city, and that the archbishop of Glasgow

was going to meet him for the sake of paying homage and obedience,

the chancellor, president- and chapter of Glasgow, on 21st June,

1510, formally declared that they were to go with the archbishop to

please the King, who was to accompany his son, the primate, and also

to please the archbishop, and not otherwise; and that they were

exempted "both by their ancient and modern privileges, granted by

the Roman pontiffs and by kings from doing homage to the primate and

to the archbishop of Glasgow and other judges ordinaries

whomsoever." They therefore solemnly protested that whatever homage

or obedience or courtesy the archbishop of Glasgow, to please his

Majesty, should render by walking in procession to meet him should

not prejudice them or their successors. [Dioc. Reg. Prot. No. 468.

The privileges of the chapter of Glasgow were ,confirmed by

Archbishop Beaton on 8th July, 1512 (Reg. Episc. No. 490).]

Long before the time

of Archbishop Beaton all the available lands in the barony of

Glasgow which had been at the disposal of his predecessors were put

into the possession of rentallers, but the earliest preserved Rental

Book, containing the record of changes in ownership, only begins in

the first year of his episcopate. After the original grant from the

bishop, as lord of the barony, a rental right might be acquired by

succession, by purchase from a rentaller, or by marrying the

daughter of .a rentaller; and a widow was entitled to hold her

husband's possession during her viduity. Relaxation of a widow's

forfeiture on remarriage was common, and when a right came by

succession to a son, and sometimes, though rarely, to a daughter,

the liferent of the surviving father or mother was invariably

reserved. It was a common practice for one member of a family to be

entered as rentaller during the lifetime of both parents, but in

that case actual possession was ,contingent on survivance. The

preserved Rental Book embodies holograph entries by the several

archbishops, recording in brief form the transmission of rental

rights between 1509 and 1570, and thus affords much desirable

information regarding the people in the barony and their estates,

some of which were •continued in direct lines of succession for many

generations. [In 1918 the corporation of Glasgow purchased from the

trustees of William Allan Woddrop, recently deceased, part of the

estate of Dalmarnock, which had come to him through ancestors and

relatives whose successive possession can be traced since 1522 (Dioc.

Reg. Rental Book, p. 83). The Rental Book was taken to Paris by the

second Archbishop Beaton, who -continued to enter the names of

rentallers therein till 1570. This book and Cuthbert Simson's

Protocol Book, 1499-1503, were published by the GrampianClub in 1875

under the title Diocesan Registers of Glasgow.] |