|

DOWN to the middle of the eighteenth

century, the years 1750 and 1760, very few "self-contained" houses

had been built in Glasgow. The ancient manses of the Cathedral

canons about the Bishop's Castle, Rottenrow, and the Drygate had

mostly fallen on evil days, ["The townhead remained a quiet

semi-rural place from the Reformation of 1560 till the erection of

the first city gasworks in 1823, inhabited by carters, cow-feeders,

and weavers, in strange contrast to the ever-changing, commercial

lower town."—Lugton's Old Ludgings of Glasgow, p. ii.] and the

wealthy merchants of the city lived, like the aristocracy of

Edinburgh till a much later date, in the flats of tenements in the

Goosedubs, Briggate, and the Saltmarket. Among the families who

lived in these quarters were the Campbells of Blythswood and their

relatives, the Douglases of Mains : and the future Duchess of

Douglas—a member of the latter family was one of the belles of

Glasgow who led the dance at the assemblies in the great hall of the

Merchants House in Briggate.

With the rise of wealth, however, came the desire for a more

ceremonious style of living. Men who had travelled abroad, and had

lived in London or Virginia or the West Indies, were no longer

content with family meals in a bedroom and entertaining their guests

in a tavern. Houses of more ambitious sort therefore began to be

built along the Trongate westward. These mansions were of a style of

architecture entirely different from that of the fifteenth and

sixteenth century manses and other dwellings in the Townhead.

Instead of crow-stepped gables and dormer windows, they had

entablatures, urns, and balustraded roofs. [See Swan's Views and

Stewart's Views and Notices.] According to Dr. J. O. Mitchell there

were fifteen of these first rank Georgian mansions built between

1711 and 1780. Of that number only two are still standing in the

twentieth century, the mansion of Allan Dreghorn of Ruchill, behind

a furniture store in Clyde Street, and that of William Cunningham of

Lainshaw, the tobacco magnate, embedded in the Royal Exchange.

The first, and for fifty years the

finest, of these new houses was the Shawfield Mansion, already

referred to, built by Daniel Campbell of Shawfield at the west end

of Trongate in 1711. For more than forty years that mansion remained

without a rival. About 1753, however, Provost Murdoch—he who

accompanied his brother-in-law, Provost Andrew Cochrane, to London

to recover the sum in which the city had been mulcted by the

Jacobite army in 1745—built the mansion which stood opposite—at the

east corner of Stockwell Street—till the end of the nineteenth

century, and was for long the Buck's Head Inn. And next to it Colin

Dunlop, Provost a few years later, built the substantial house

which, with its tympanum front, formed a feature of the Trongate

till well into the twentieth century. [Glasgow and its Clubs, p. 43

note.]

The extension of the city westward

brought about the demolition of an ancient landmark. Of Glasgow's

eight main " ports " or gateways which existed in 1574—the

Stablegreen Port, the Gallowgate Port, the Trongate or West Port,

the South or Water Port, the Rottenrow Port, the Greyfriars Port,

the Drygate Port, and the Port beside the Castlegate [Glasgow and

its Clubs, p. ii.] —the West Port had already been removed from the

neighbourhood of the Tron to the head of the Stockwell. In 1751 it

was ordered to be demolished altogether. [Burgh Records, 22nd Jan.]

The developments which followed,

immediately to the westward, were owed to the civic aristocracy,

whose fortunes were made out of the wonderful trade with Virginia,

and who came to be known as the "tobacco lords." Of these some of

the most notable individuals were the members of the Buchanan

family. Their ancestor was George Buchanan, younger son of the laird

of Gartacharan, near Drymen, who, to push his fortunes, came to

Glasgow in the "killing times," fought for the Covenanters at

Bothwell Bridge, and for a time had a price set upon his head. After

the Revolution he appears as a prosperous maltster, visitor of the

Maltmen, and deacon-convener of the Trades' House. His four sons all

prospered. They were the founders of the Buchanan Society in

1725—George Buchanan of The Moss and Auchentoshan, Andrew Buchanan

of Drumpellier, Archibald Buchanan of Silverbanks or Auchentorlie,

and Neil Buchanan of Hillington in Renfrewshire, M.P. for the

Glasgow burghs. Of these the eldest was a maltman like his father,

city treasurer in 1726, and a bailie in 1732, 1735, and 1738. He

built himself a fine mansion on the north side of the Westergate,

now Argyle Street—on the site occupied later by Messrs. Fraser &

Son's warehouse—and he died, a wealthy merchant, in 1773.

[Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, p. 3. The Old Country Houses of

the Glasgow Gentry, p. 186.] His son Andrew, again, born in 1725,

built another mansion a little farther west, and on the four acres

of land behind it planned the modern Buchanan Street. He was ruined

and his plans were interrupted by the American War of Independence,

but these were carried out by the trustees of his estate, one of

whom was the celebrated Robin Carrick of the Ship Bank. The first

house in the street, built about 1777, stood a little north of the

site of the present Arcade, and was that occupied for many years by

John Gordon of Aikenhead. The next was that of his brother

Alexander—"Picture Gordon"—a fine mansion facing the site of the

modern Gordon Street, which was the residence later of Henry

Monteith of Carstairs. [Frazer's Making of Buchanan Street, p. 41.]

Meanwhile the second of the four

brothers, Andrew of Drumpellier, born in 1690, had been among the

first to take advantage of the opening Virginia trade. While still

comparatively young he had five vessels at sea in that business. The

double profits of the outward and inward trade enabled him, like

others of his neighbours, to amass a large fortune in a few years.

He was chosen Dean of Guild in 1728 and Provost in 1740 and 1741. It

was he who in the former year was empowered to borrow £3000 from the

Royal Bank for the purchase of meal to feed the poor of the city.

When the Jacobite army invaded Glasgow in 1745, and its

quarter-master, Hay, demanded £500 from him with the threat that, if

he refused, his house would be plundered, his reply was, "Plunder

away: I wont pay a single farthing!" Having purchased the country

estate of Drumpellier, he proposed, like his friends Provost Murdoch

and Colin Dunlop, to build a handsome city residence for himself,

and to that end purchased a number of small properties, malt-kilns,

and vegetable gardens extending from the Westergate to the Back Cow

Loan. He cleared away the barns, byres, and malt-kilns on the

ground, laid out a roadway, which he named Virginia Street,

northward from the Wester-gate, and proceeded to sell plots for the

building of mansion houses. The first of these plots, on the east

side of the street, he disposed of in 1753 to his brother, Archibald

Buchanan of Silverbanks or Auchentorlie, who built on it a handsome

mansion with a short double stair in front in the style of the time.

[Eleven years later the Silverbanks mansion was purchased by Sir

Walter Maxwell of Pollok and the partners of the Thistle Bank, which

occupied it for eighty years. On its site was afterwards built the

ill-fated City of Glasgow Bank.—Glasghu Facies, ii. 1019.] Five

years later the plot to the south of this, at the corner of the

street, was acquired by the Highland Club, which built on

the spot the famous Black Bull Inn.

But before Andrew Buchanan could bring his plans to fruition, death

stilled his ambitions and he was laid in the Ramshorn kirkyard in

1759. The traffic of modern Ingram Street rumbles over the stout old

Provost's dust. [Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, pp. 4, 6, 12,

15, 17. Glasgow Past and Present, p. 517.]

While Andrew Buchanan's elder son

James inherited Drumpellier and was twice elected Provost of

Glasgow—from his facial peculiarities he was known as "Provost

Cheeks"—the younger son, George, became owner of the Glasgow

property. Carrying out his father's plans he built on the northern

end of his ground, next the Back Cow Loan, a handsome residence

which eclipsed even its neighbour, the Shawfield Mansion, and was

certainly the grandest house yet built by a Glasgow tobacco lord.

The Virginia Mansion, as it was called, was indeed a splendid

residence, with a gateway about the line of the present Wilson

Street, porters' lodges on each side, and vineries and peach-houses

against its garden walls. Already, before he was thirty, its owner

had purchased the estate of Windyedge in Old Monkland, east of

Glasgow, had laid out the grounds there with great taste, and had

given it the name of Mount Vernon—which it still bears—in honour of

his friend, George Washington, whose estate of that name neighboured

his own in Virginia. He did not live long, however, to enjoy his

great possessions. In July, 1762, he was carried from the Virginia

Mansion to the family burial-place in the Ramshorn kirkyard, a few

hundred yards away.

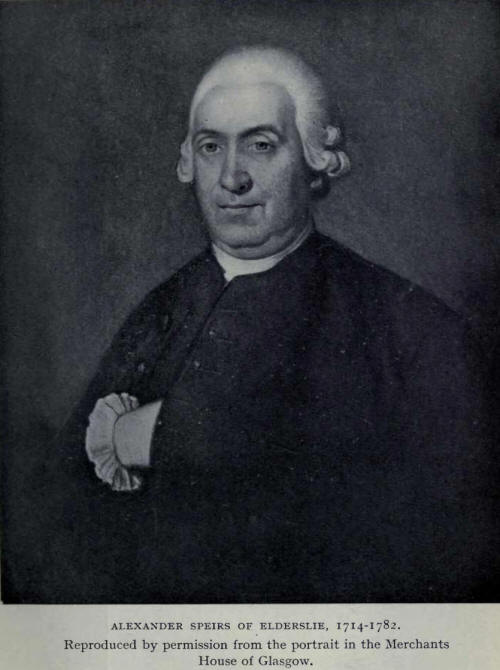

Meanwhile building plots in Virginia

Street had been sold to other two of the great tobacco traders, John

Bowman of Ashgrove, afterwards Provost of Glasgow, and Alexander

Speirs, afterwards of Elderslie. The latter was an incomer from

Edinburgh who had been attracted to the western city by the prospect

of fortune in the Virginia trade. He purchased plots of ground on

each side of Virginia Street, just outside the gates of the Virginia

Mansion, built himself a house on the western side, and proceeded to

ally himself with the merchant aristocracy of the city by marrying

Mary, daughter of Archibald Buchanan of Auchentorlie. The lady's

mother was a daughter of Provost Murdoch and niece of Provost Andrew

Buchanan of Drumpellier and Neil Buchanan of Hillington, M.P. for

the Glasgow burghs. [Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, pp. 20 and

22. Glasghu Facies, ii. 1030.]

Alexander Speirs was one of the four

young men, who started at one time in business, to whose talents and

spirit Provost Cochrane attributed the sudden rise of Glasgow to

trading opulence. The four, he said, had not io,000 among them when

they began. They were William Cuninghame, afterwards of Lainshaw,

Alexander Speirs of Elderslie, John Glassford of Dougalston, and

James Ritchie of Busby. [Sir John Dalrymple, Memoirs of Great

Britain and Ireland, appendix, quoted by Strang, Glasgow and its

Clubs, p. 42.] Of the four, Speirs is the only one whose descendant

retains his position and possessions at the present day. [Many of

the personal possessions of the old tobacco lord, including his

snuff-box and his tall gold-headed malacca cane, are preserved by

his great-great-grandson, Mr. A. A. Hagart Speirs of Elderslie, at

Houston House, his seat in Renfrewshire.] He prospered rapidly, was

one of the founders of the Glasgow Arms Bank in 1750, and was the

greatest of all the importers of tobacco. Of 90,000 hogsheads

imported into Britain in 1772, 49,000 were imported by the merchants

of Glasgow. Of these, Alexander Speirs & Co. imported 6035 hogsheads

and John Glassford & Co. 4506. [Glasgow Past and Present, p. 521.]

This business was conducted in a style befitting its importance.

Among its chief customers were the Farmers-General of France, who on

one occasion at any rate gave a single order for six thousand

hogsheads. The orders of the Farmers-General were transmitted

through Forbes's Bank, and Sir Charles Forbes describes how he and

his partner, Mr. Herries, on one occasion journeyed from Edinburgh

to Glasgow to adjust certain purchases. "As we went on a very

agreeable errand," he says, "we were received with open arms, and

entertained in the most sumptuous manner by the merchants during the

time that we remained there." [Memoirs of a Banking House, p. 44.]

For the purpose of such entertainments a handsome house was

necessary. Accordingly in 1770 Speirs purchased the fine Virginia

Mansion from the trustees of the late George Buchanan, of whom he

was himself one. At the same time, with fortune on a rising tide, he

set about the creation of a country estate. He bought a goodly

number of the little properties of the bonnet lairds of Govan, and

acquired the estate of Elderslie, the reputed birthplace of the

Scottish patriot, Sir William Wallace, from the last of that family,

Helen Wallace, wife of Archibald Campbell of Succoth and Garscube,

with other lands—altogether some io,000 acres—in Renfrewshire. He

had the whole consolidated into a barony under the name of Elderslie,

holding of the Crown, and on the historic King's Inch, by the river

side, built a stately mansion, to be known as Elderslie House. The

mansion took five years to build, and late in 1782 Speirs

established himself there with his family. Alas, before the year

closed he was dead, but he had the satisfaction of knowing that he

had accomplished his ambition and had founded a territorial house.

[Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, p. 21. Mitchell's Old Glasgow

Essays, P. 315. The portraits of Alexander Speirs and his wife hang

in the Merchants House.]

Rivalling Alexander Speirs in

importance among the great tobacco traders was John Glassford of

Whitehill and Dougalston. A native of Paisley, where his father was

a merchant and magistrate, Glassford attained prosperity in the city

while still a young man. In 1739, while only twenty-four, he rode to

London in company with Andrew Thomson of Faskine, afterwards founder

of the bank bearing his name. They rode their own horses, and were

evidently men of means. [The difficulties of their journey are

detailed in Dugald Bannatyne's notebook, quoted in Pagan's Glasgow

in 1847, and in Cleland's Statistical Tables, 1832, p. 156.] Some

half-dozen years later, after the Jacobite rebellion, Glassford

acquired Whitehill, part of the old Easter Craigs of Glasgow, and

now embodied in Dennistoun. He enclosed the whole thirty acres with

a wall, built a country mansion, and laid out the place with

gardens, conservatories, and ornamental walks. For twelve years he

resided there, dispensing princely hospitality and driving daily to

and from the city in a coach and four. But in 1759 he purchased, for

17oo guineas, the famous Shawfield Mansion in Trongate from the

second William Macdowall of Castle Semple, son of the West Indian

magnate. He then sold Whitehill to another Virginia merchant, John

Wallace of Neilstonside and Cessnock, a descendant of the family

which gave Scotland its patriot hero. From that time till his death

in 1783 Glassford lived partly in the Shawfield Mansion and partly

at the beautiful estate of Dougalston, which he also acquired, near

Bardowie Loch, a few miles north of the city. Like Alexander Speirs

he was early allied by marriage with the ruling caste in Glasgow,

his sister Rebecca being the wife of Archibald Ingram, founder of

the printwork industry, and Provost of the city in 1762. But his own

matrimonial alliances were more ambitious still. Of his first wife

nothing is known ; his second marriage was with Anne, second

daughter of Sir John Nisbet, Bart., of Dean, now part of Edinburgh,

and his third wife was Lady Margaret Mackenzie, daughter of the last

Earl of Cromarty. He carried on business on a great scale, had

twenty-five ships with their cargoes on the sea at once, and turned

over annually more than half a million sterling. [Tobias Smollett,

quoted in Glasgow and its Clubs, p. 39. Glassford's office, in the

third storey of the town's tenement at the corner of Gallowgate and

High Street, cost him £13 per annum. The floor below was rented by

Provost Andrew Cochrane at £14.---Burgh Records, 12th Nov. 7747.] In

addition he was concerned in various local enterprises. He was a

chief partner in the Glasgow Tanwork Company, perhaps the largest in

Europe in its time. He was one of the first partners in the Glasgow

Arms Bank, started in 1750. He was principal partner in the original

cudbear factory, which carried on the rather odorous business of

dye-making from certain Highland lichens. With his brother-in-law,

Provost Ingram, he had a share in the Print-field at Pollokshaws.

And he was a leading partner in the aristocratic Thistle Bank, whose

business lay largely among the rich Nest Indian merchants. It was

largely, also, his support, with that of one or two other wealthy

merchants, which enabled the Foulis brothers to carry on their

famous Academy of the Fine Arts. By Tobias Smollett, who as a

surgeon's apprentice must often have looked with awe on the great

man pacing the plainstanes, he is commemorated in the pages of

Humphry Clinker. He died at the age of sixty-eight in the Shawfield

Mansion, and lies, along with his second and third wives and several

of his descendants, in the Ramshorn churchyard, close behind the

railings in Ingram Street. [Glasghu Facies, pp. 757, 956. Glasgow

Past and Present. Mitchell, Old Glasgow Essays, pp. 80, 122.

Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, p. 215. Country Houses of the

Old Glasgow Gentry. Burgh Records, 12th Nov. 1747.]

Nine years after John Glassford's

death, his trustees sold the Shawfield Mansion for £9850 to William

Horn, a builder, who demolished the house, and over its site, and

through the great garden behind, formed the thoroughfare now known

as Glassford Street. [Glasgow and its Clubs, p. ii. Mitchell, p.

22.] A street branching from it long bore the name of Garthland

Street, from the estate of the Macdowalls, once the owners of the

site. This has lately been changed to Garth Street.

Of different fate from the Shawfield

Mansion and the Virginia Mansion, the splendid dwelling built by

another of these great tobacco lords still remains to testify to the

wealth and taste of that time. William Cuninghame was another of

Provost Cochrane's " four young men." When the American War of

Independence broke out he was a junior partner in the firm which

held the largest stock of tobacco in the United Kingdom. The average

cost of their great stock had been threepence per pound. Immediately

upon the declaration of independence by America the price rose to

sixpence. Thereupon seeing they had doubled their capital, the

partners of the firm held a meeting, and resolved to take advantage

of the opportunity and effect an immediate sale. The British forces

in America, it was thought, must shortly suppress the rebellion,

whereupon plentiful supplies of tobacco would again become

available, and the price would fall to its previous level. But Mr.

Cuninghame was of a different opinion. He took over the whole stock

as his personal property, and was able to give the other partners of

the firm security for the amount of his purchase. His judgment

proved to be correct. In consequence of the misfortunes to the

British armies tobacco continued to rise in price till it reached

the astonishing figure of three shillings and sixpence per pound. By

that time Cuninghame had sold his entire stock at an enormous

profit, and had realized a very handsome fortune. With this he

bought the fine estate of Lainshaw in Ayrshire, and proceeded to

build himself a splendid residence in Glasgow. On the west side of

the Cow Loan, which is now Queen Street, and facing the Back Cow

Loan, now Ingram Street, stood at that time a cow-feeder's thatched

steading with byre and midden, the property of one Neilson, a "land

labourer in Garioch," near Maryhill. Here Cuninghame saw

possibilites, as Sir Walter Scott did later in the Tweedside farm of

Clartyhole. He purchased the steading, and on its site in 1778

raised one of the finest houses of its time in the West of

Scotland—at a cost, it is said, of £10,000.

After several changes of ownership

this mansion still stands. At Cuninghame's death in 1789 it was

bought by the great firm of William Stirling & Sons, which used one

of the wings as an office, while the main building was occupied by

successive members of the family. In 1817 the house was purchased by

the Royal Bank, which built a double stair in front and installed

its tellers in the drawing-room. Ten years later, the old

coffee-room at the Cross having become too small for their

meeting-place, an association of merchants, with James Ewing of

Strathleven at its head, acquired the house and built round it, to

the plans of the architect Hamilton, the present handsome Royal

Exchange. The old Lainshaw mansion still stands behind the

colonnaded Queen Street front, its rooms being mostly occupied as

shipbroking and insurance offices. [Curiosities of Glasgow

Citizenship, p. 193. Alison's Anecdotage, p. 127. Other sites

proposed for the new Exchange were between Virginia and Miller

Streets in Argyle Street, and at the head of Glassford Street, and

the Town Council supported the Argyle Street location.—Burgh

Records, 25th May, 1827.]

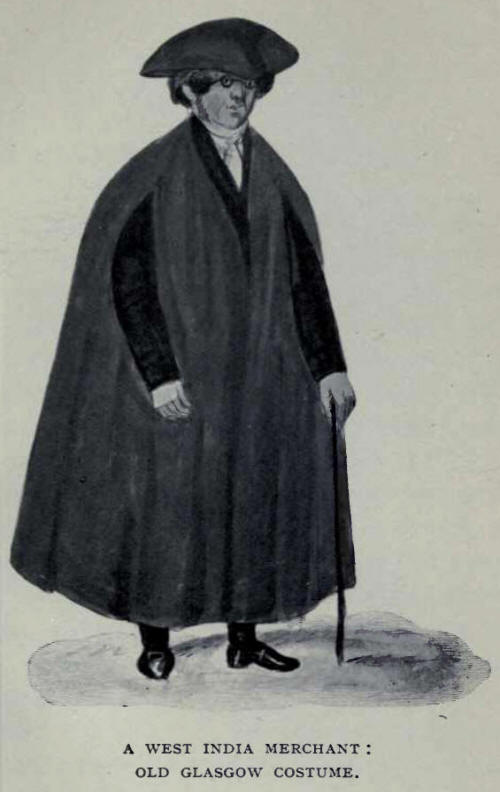

These were the most notable of the

Glasgow merchants who realized fortunes out of the trade with the

American colonies, who trod the plainstanes at the Cross in scarlet

cloaks and three-cornered hats, and, known as "tobacco lords,"

formed a civic aristocracy of hauteur and exclusiveness that have

not been forgotten at the present day. [Glasgow and its Clubs, p.

40.] The trade lasted for fifty years, and came to an end with the

declaration of independence by the United States. Upon that event

the estates owned by many British subjects in America were

confiscated, and the owners were ruined. Among those who suffered in

this way was the father of the famous Mrs. Grant of Laggan,

authoress of Letters from the Mountains, Memoirs of an American

Lady, and the well-known song, "O where, tell me where." Captain

McVicar was a resident in the Goosedubs, then a fashionable quarter

of the city, where his daughter was born. Shortly afterwards he was

ordered with his regiment to America, where he took part in the

conquest of Canada. Some years later he resigned his commission,

took up his allotment of 2000 acres in Vermont, and acquired the

similar allotment of a brother officer. In 1768 he was compelled by

ill-health to return to Scotland, and on the outbreak of the

revolutionary war was deprived of his estate and reduced to depend

on an appointment as barrack-master at Fort Augustus.

Another family which suffered in

similar fashion was that of Hugh Wyllie, who died suddenly after his

election to the Lord Provostship in 1781. His property was in

America; no remittances came home after his death, and the Town

Council granted his widow £50 per annum, to be repaid when

remittances were received. [Burgh Records, 18th Nov. 1782.]

Soon after the declaration of

independence by America the "tobacco lords" ceased to lead the

social life of the city, and the scarlet cloaks gradually

disappeared from the plainstanes of the Trongate.

|