|

UPON the final clearing away of the

Jacobite menace, after the battle of Culloden in 1746, Glasgow found

prosperity flowing upon it in a rising tide. One of the most

significant evidences of this development was the establishing of

the joint-stock banks, which began in the year 1750. Previously the

working of finance in Scotland had been rather a cumbrous business.

Down to the time of George Hutcheson, the Glasgow notary, money

could only be borrowed on the security of actual property—wadsets or

bonds upon landed estates, or the deposit of jewels and other

valuables. In The Fortunes of Nigel Sir Walter Scott gives a fair

picture of the latter process in the dealings of King James VI. with

the Edinburgh goldsmith and money-lender, George Heriot. George

Hutcheson introduced the less cumbrous method of lending money upon

the personal security of responsible guarantors, and sixty years

later the Darien Company carried matters further when it granted

loans to its subscribers on the security of their holdings of its

own shares. Edinburgh led the way in the setting up of regular

joint-stock banks in Scotland. The Bank of England had been founded

in 1694 on the plan of the Dumfriesshire farmer's son and West

Indian merchant, William Paterson, and, following its example, the

Bank of Scotland had been incorporated in the following year. Its

capital to begin with was £100,000, the amount called up £10,000,

and its business limited to the advancing of money on bills and

bonds by the issue of notes for sums of £5, £10, £50, and £100

sterling. A second company, the Royal Bank of Scotland, was

established by charter in 1727 with, for its capital, a large part

of the debentures, amounting to £248,550, which had been issued in

payment of the Scottish national debts, and upon which interest of

£10,000 per annum was to be paid out of the Scottish customs and

excise. Little more than a fourth part of the capital of this

company was held in Scotland, so the Royal had only a branch office

in Edinburgh, but its first governor was Archibald, Earl of Ilay,

afterwards third Duke of Argyll. [Hist. of Royal Bank of Scotland,

by Neil Munro, p. 34.] One of

the difficulties of these early banks is illustrated by an incident

which took place on 27th March, 1728. On that day Andrew Cochrane,

Provost of Glasgow, presented at the office of the Bank of Scotland

£900 of its notes for change into coin of the realm. There was none

to give him. Two-thirds of the capital of the bank and all its notes

had been lent out on heritable and personal bonds, which could not

be immediately turned into cash, and already there had been a run on

the bank for the cashing of its notes, engineered, it was suspected,

by the rival Royal Bank, which had emptied the till. The bank

claimed the privilege of deferring payment of cash, and promised

interest until payment was made. The Court of Session upheld this

claim, but Provost Cochrane carried the case to the House of Lords,

which reversed that decision and declared that banks must meet their

promises to pay in the same manner as private individuals. [Ibid. p.

60.] In this matter the stout Glasgow provost vindicated the

principle upon which the entire integrity and success of the

Scottish banking system since then have been based.

The banking experience of the western

city itself had been suggestive enough. In 1696, the year after its

foundation in Edinburgh, and again in 1731, the Bank of Scotland had

opened branch offices in Glasgow, but had closed them after a short

experience. The reason usually given

for this want of success is that the bank would not deal in bills of

exchange. [Buchanan's Ranking in Glasgow during the Olden Time.]

There is room, however, to surmise that the enterprise laboured in

Glasgow under the prevalent feeling that the promoters of the Bank

of Scotland were more or less Jacobite in sentiment. Its Tory

directors had opposed the Treaty of Union, its treasurer was a

Jacobite, and the Government was known to suspect its political

sympathies. [Hist. Royal Bank, p. 52.] On the other hand the Royal

Bank was notedly Hanoverian in sympathies. Its governor and the most

active members of its staff were Campbells, and it was known to have

the warm support of the Duke of Argyll, the victor of Sheriffmuir.

It was significant that when the Government granted compensation to

the city for its losses on account of the Jacobite visitation of

1745, the money was paid through the Royal Bank, [Burgh Records, 8th

Nov. 1749.] and when in the year of the great frost Glasgow found it

necessary to borrow a large sum for the feeding of the poor, it was

from the Royal Bank that the money was obtained. [Hist. Royal Bank,

p. 86.] But the Royal had no branch in the western city till 1783,

when the famous Glasgow citizen, David Dale, was appointed joint

agent there.

Meanwhile in Glasgow a considerable

banking business was carried on by private traders. In the Edinburgh

Evening Courant in July, 1730, James Blair, merchant, at the head of

Saltmarket, advertised that, at his shop there, "all persons who

have occasion to buy or sell bills of exchange, or want money to

borrow, or have money to lend on interest, etc., may deliver their

demands." It was not till 1750 that the hour struck when Glasgow was

to have a bank of its own. At that time the largest banking business

in the city was probably being done by the Glasgow Tanwork Company,

which carried on its ordinary operations, with tanning pits and

other appurtenances, beside the Molendinar, near the Gallowgate.

Among its patrons were Provost Andrew Cochrane and many other

notable merchants. Fifteen years later, in 1765, its deposits

amounted to no less than £40,000. [The Tanwork Company was entrusted

with large deposits from many parts of Scotland, on which it paid

interest at 4½ and 5 per cent. A list of the depositors and the sums

at their credit is given by Senex in Old Glasgow and its Environs,

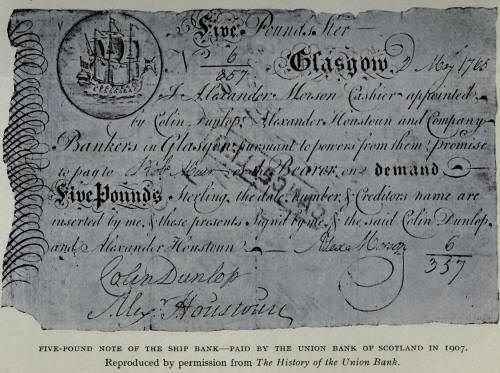

p. 123.] It was in January,1750, that the first regular Glasgow bank

began business in a small office in the old dwelling of the Coulters

at the south corner of Briggate and Saltmarket. [Photograph in The

Old Ludgings of Glasgow, p. 58.] Its partners were William McDowall

of Castle Semple, Andrew Buchanan of Drumpellier, Allan Dreghorn of

Ruchill, Robert Dunlop, merchant, Colin Dunlop of Carmyle, and

Alexander Houston of Jordanhill, all men of wealth and high standing

in the city. It was known as the Ship Bank, and its operations were

carried on under the firm name of Colin Dunlop, Alexander Houston &

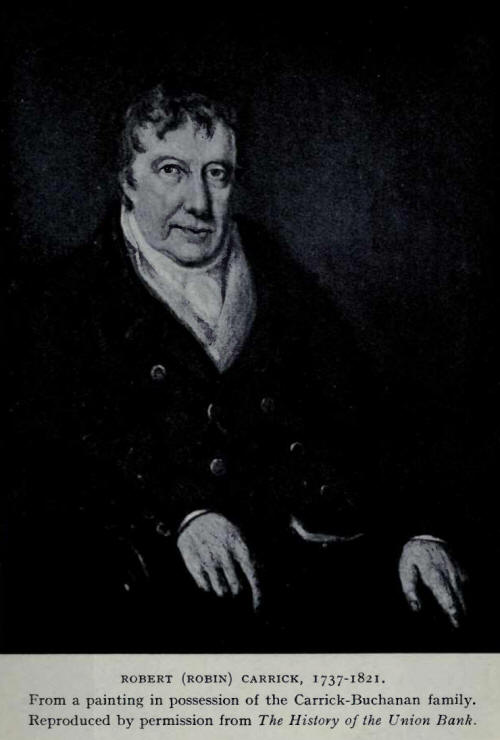

Co. It owed its success largely to the unremitting labours of the

famous Robin Carrick, its manager for a long lifetime. "Sicker,

far-seeing, resolute, passionless, spending his days in the dingy

Bank parlour, and his lonely, joyless evenings in the old flat

above, he died there on 20th June, 1821. [Mitchell, Old Glasgow

Essays, p. 21. There remained, nevertheless, one grain of sentiment

under the hard crust of the grim old banker's nature. George

Buchanan, the great Tobacco Lord, builder of the famous Virginia

Mansion, when at the height of his fortunes had employed a divinity

student as a tutor for his family, and afterwards got him inducted

as parish minister of Houston. Later, when George Buchanan's son,

Provost Andrew Buchanan, was helping to found the Ship Bank, he got

his old tutor's son, Robin Carrick, then about fourteen, a place as

message boy in the establishment. When the crash came to the tobacco

trade, with the revolt of the American colonies, the Buchanans were

ruined. But Provost Andrew's brother, David, when the war was over,

went to the United States, and recovered enough of the family

fortunes to return and purchase again his grandfather's estate of

Drumpellier. He was again on the verge of ruin through a law plea in

America, when Robin Carrick died, and it was found that he had left

nearly his whole fortune to the son of his father's old patron. From

that circumstance the Buchanans of Drumpellier took the name of

Carrick-Buchanan. Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, p. 25.

Mitchell, Old Glasgow Papers, p. 164.] He was eighty-one years of

age, and left about a million sterling Not to be outdone by their

rivals in business, another group of Glasgow merchants, with Andrew

Cochrane at their head, started the Glasgow Arms Bank in November of

the year in which the Ship Bank opened its doors. There were

twenty-six partners, and the office was a small place up a narrow

stair, also in that fashionable business quarter, the Briggate. It

carried on business under the name of Andrew Cochrane, John Murdoch

& Company.

The procedure adopted by these banks

and the others that followed them was to lodge in the hands of the

Town Clerk bonds signed by all their partners guaranteeing payment

of their notes. In their case a "seal of cause," such as the

Magistrates and Town Council granted to the various crafts and

incorporations to enable them to sue and be sued and to hold

property as corporate bodies, was not required, but the joint

guarantee of all the partners, thus duly registered, served a not

less important purpose.

Threatened with this rivalry in the

western city, the two Edinburgh banks joined forces in a rather

ungenerous attempt to put the Glasgow banks out of business. For

this purpose they employed a rather despicable individual. Alexander

Trotter, an Edinburgh accountant, who had been an early partner in

the afterwards great banking firm of Coutts & Company, was sent to

Glasgow. There he set about the business of embarrassing the new

private banks by collecting their notes, and then presenting them in

large amounts and demanding payment in cash. The Glasgow bankers met

the attacks by paying out the money in sixpences, a device which had

been adopted by the Edinburgh banks themselves in a similar

emergency. On one occasion a whole forenoon was taken to make a

payment of, and the total amount thus cashed in thirty-four business

days was £2893. Trotter, on 23rd January 1759, made a formal

protest, then brought an action in the Court of Session against the

Glasgow Arms Bank for payment of the notes which he held, amounting

to X3447, with interest from the date of his protest, as well as 600

damages. He also asked it to be declared that the bank had no powers

to limit its hours of business, but must cash its notes on demand at

any time between seven in the morning and ten at night. The case

drifted on for four years, and was in the end taken out of Court on

the bank paying Trotter £600. The amount probably did no more than

cover his expenses, and the Glasgow Arms Bank had secured the

purpose of its defence. [The Scotsman, 5th April, 1826. Forbes,

Memoirs of a Banking House, 2nd ed., p. 5. Reproductions of the

notes of some of these old Glasgow banks, with interesting details

regarding their signatories, are printed in Frazer's Making of

Buchanan Street, pp. 5-8.]

During the next half-century a number

of other private banking companies were established in Glasgow. In

1761 the Thistle Bank was set up by Sir Walter Maxwell of Pollok and

partners; in 1769 the Merchant Banking Company by a number of small

traders in the Saltmarket ; in 1785 Thomson's Bank, by a father and

two sons of that name; and in 1809 the Glasgow Bank, at the

south-west corner of Montrose and Ingram Streets, was founded and

managed by James Dennis-ton of Golfhill. [Glasgow Past and Present,

p. 462; Curiosities of Citizenship, p. 141.] At a later day the

oldest and the latest of these banks united to become the Glasgow

and Ship Bank, and later still, along with the Thistle Bank, were

embodied in the Union Bank of Scotland. The Glasgow Arms Bank and

the Merchant Banking Company stopped payment during the crisis of

the French Revolution, but paid their creditors in full. [Hist.

Royal Bank, p. 156.]

It cannot be doubted that the credits

and other facilities afforded by these banks played a large part in

developing the trade and industry of Glasgow in the second half of

the eighteenth century. Nor was the Town Council slow to avail

itself of the financial convenience which the banks afforded.

In 1754, when considerable expense

fell to be incurred in improving certain turnpike roads leading into

the city—the Renfrew and Three Mile House roads, and the road from

Gorbals by Paisley Loan to Govan—it was arranged to take credit

"from any of the banks in the city" to defray the cost, till this

could be recovered out of the tolls. And a few months later it was

agreed to open an account with the "new bank company," otherwise the

Glasgow Arms Bank, upon which the Provost was empowered to draw sums

for the town's use up to a total amount of £1000. [Burgh Records,

16th April, 26th Sept. 1754.]

Another enterprise which the rising

trade of Glasgow quickened with astonishing effect was the deepening

and improvement of the harbour. Again and again in the two hundred

years since it became a self-governing community the city had made

efforts to secure its passage to the open sea. As long ago as the

year 1566 it had joined with the burghs of Renfrew and Dunbarton in

an attempt to deepen the channel at Dumbuck, [Cleland's Annals,

1817, p. 371.] and again in 1611, after securing from James VI. the

freedom of the river "from the Clochstane to the Brig of Glasgow,"

it had sought the advice of Henry Crawfurd, the Culross engineer,

and under his direction had again attacked the obstruction at

Dumbuck with chains, ropes, hogsheads, and other apparatus. [Burgle

Records, i. 329.] But these efforts still left the river little more

than a shallow salmon stream. Over a hundred years had elapsed since

William Simpson, that native of St. Andrews whom McUre describes as

"a great projector" of Glasgow trade, "built two ships at the

Bremmylaw, and brought them down the river the time of a great

flood." When the first Glasgow vessel to trade with Virginia, a

craft of sixty tons, was built on the Clyde in 1716, the work had to

be done at Crawford's-dyke, between Port-Glasgow and Greenock, as no

natural flood would have been great enough to float her down the

river. Port-Glasgow, it is true, in the fifty years of its history

had thoroughly justified its existence, but the conveyance of the

transhipped cargoes between that seaport and the parent city still

presented serious difficulties by reason of the sandbanks, islands,

and shallow channel of the Clyde. Notwithstanding these hindrances,

the extension of trade made it necessary in 1723 to enlarge the quay

at the Broomielaw, and the Town Council, the Trades House, and

probably the Merchants House, spent I833 6s. 8d. sterling in

extending it as far as "St. Tennochis burn foot, opposite to the

Dowcat Green"—that is, about the present Dixon Street, where the

Dowcat or Old Green began. [Burgh Records, 22nd June, 1722; 12th

Nov. 1724.] Regarding the harbour, as thus improved, McUre, a few

years later, indulged in one of his bursts of eloquence. "There is

not," he says," such a fresh water harbour to be seen in any place

in Britain. It is strangely fenced with beams of oak, fastened with

iron bolts within the wall thereof, that the great boards of ice in

time of thaw may not offend it ; and it is so large that a regiment

of horse may be exercised thereupon." [Hist. Glasg., 1830 ed., p.

231, append. 347.]

McUre's remarks may have helped to

stimulate further enterprise, for in 1736, the year in which his

History was published, the Town Council ordered an inspection to be

made of the sandbanks in the river below the Broomielaw, and agreed

to expend £20 sterling "for an experiment upon one of the sandbanks

for clearing the river." [Burgh Records, 2nd July, 1736.] In this

small and tentative fashion was begun again the great engineering

achievement which in two hundred years has made the Clyde at Glasgow

one of the most commodious harbours in the world.

Four years later another effort was

made to remove the sandbanks below the Broomielaw. The magistrates

were empowered to "go the length of £100 sterling of charges

thereupon," and to build a flat-bottomed boat "for carrying off the

sand and shingle from the banks." [Ibid. 8th May, 1740. Instead of

building a new boat the magistrates requisitioned and repaired "the

Port Glasgow dirt boat."—Ibid. 29th Aug. 1740.]

Just then the success of the rising

harbour town of Greenock may have given a spur to the efforts of

Glasgow. Under the energetic guidance of its superior, Sir John

Shaw, that place had developed into a thriving port, and secured the

charter of a royal burgh, and in 1740 had repaid all the capital

expended upon its harbour, and realized a surplus of 27,000 merks or

£1500 sterling. Its customs realized over £15,000 per annum. [Weir's

Hist. of Greenock, p. 42. Williamson's Old Greenock, p. 75.]

Greenock clearly was a possible rival by no means to be despised.

In 1743 came a petition from the

shipmasters of Glasgow and the Clyde ports for the setting up of a

lighthouse on the Little Cumbrae, already referred to, though an Act

of Parliament for the purpose was not secured till 1756. [Burgh

Records, 17th Feb. 1743; 16th June, 1756.] A similar petition was

received in 1751 from the merchants and feuars in Port-Glasgow,

offering to supervise the marking of the channel with buoys and

perches, and asking that the "mud boat" be constantly employed in

cleaning the harbour there. To these proposals the Magistrates and

Council promptly agreed. [Ibid. 22nd Jan. 1751.]

For the interests of Glasgow itself,

however, the improvement of the channel of the upper river was a

matter of more vital and immediate importance. Upon this subject the

Town Council again proceeded to seek the best expert advice. James

Stirling, manager of the Scots mining company's works at Leadhills,

was a noted mathematician and engineer. One of his numerous papers

contributed to the Transactions of the Philosophical Society

described "A Machine to Blow Fire by the Fall of Water." [Stirling's

career forms the subject of an article in Mitchell's Old Glasgow

Essays. Third son of Alexander Stirling of Garden, he was expelled

from Oxford because of his Jacobite connection, lived as a professor

of mathematics at Venice for some years, but, having discovered the

secret of plate-glass making, had to flee for his life in 1725. For

ten years he taught mathematics in London, enjoying the friendship

of Newton and other men of science, till in 1735 he was appointed

manager of the mines at Leadhills.] His idea was to make Glasgow

accessible to vessels of larger size by the building of locks on the

river. "For his service, pains, and trouble in surveying Clyde,

towards the deepening thereof by locks," the Town Council presented

him with a silver tea-kettle and lamp, engraved with the city arms,

at a cost of £28 4s. 4d. sterling. [Burgh Records, i. July, 1752.]

Fortunately Stirling's

recommendations were not carried out, nor were those, three years

later, of John Smeaton, engineer of the Eddystone Lighthouse and of

the Forth and Clyde Canal. Between Glasgow Bridge and Renfrew

Smeaton found twelve shoals, four of which had no more than eighteen

inches depth at low water and one, some four hundred yards below the

bridge, only fifteen inches. His proposal was that a weir and lock

should be constructed at Marling Ford, about four miles below the

bridge, to allow vessels seventy-six feet long and of

four-and-a-half feet draught to pass up to the Broomielaw at all

states of the tide. Had these recommendations been carried out they

might have restricted the possibilities of the harbour of Glasgow

for all time. But Smeaton was paid twenty guineas for his advice and

the Merchants House and the Trades House proceeded to urge the Town

Council to apply to Parliament for authority to proceed with the

work. They declared themselves willing to pay such dues on all

vessels passing through the locks as would recoup the city for the

expense entailed. [Burgh Records, 5th Aug. 1757; 13th March and 11th

April, 1758.] Smeaton was accordingly invited, in 1758, to elaborate

the details of his scheme. At the same time Alexander Wilson, the

famous typefounder, was employed to

make a survey of the river.

Parliament was approached, and in due course an Act was secured—the

first of the Clyde Navigation Acts—empowering the Town Council to

carry out the enterprise. [George II. C. 62. Burgh Records, 13th

March, 1758; 9th Jan. 1759; 31st May, 1759.] The Act empowered the

Town Council to deepen the river from Dumbuck Ford to Glasgow

Bridge, to make locks and weirs, and to carry out other necessary

works. To this end £3200 were borrowed, and preparations were made

for the construction of a lock, but on account of the difficulties

encountered the scheme was in the end abandoned. [Burgh Records,

10th Aug. 1759. For details of the various schemes to improve the

harbour see The River Clyde, by James Deas, engineer to the Clyde

Navigation Trust, 1876. A contract was actually made with Smeaton to

construct a lock and dam at the Marlingford, and in 1762 the work

was going on (Burgh Records, 24th Nov. 1760; 25th Jan. 1762).

Shortly afterwards, however, it was stopped, and Freebairn, an

Edinburgh architect, who had been appointed master of works, made a

claim for his broken engagement (Ibid. 3rd Jan., 13th May, 1763).

Smeaton's tavern bill at the Exchange coffee-house while he was

making his plan amounted to £18 10s. (Ibid. 26th Jan. 1761).]

In 1764 another suggestion was made

which may have afforded the idea for the plan which was actually

carried out. At the desire of several of the merchants one Dr. Wark

submitted a proposal for deepening the river by means of its own

current. His idea was to confine the current by means of a whin or

furze dyke two or three yards broad. The difficulty in this case

seems to have been to secure a sufficient supply of furze, and,

probably for this reason, nothing more was done with the proposal.

[Ibid. 26th April, 1764.]

It was not till 1768 that the project

was taken up again. The Town Council then consulted John Golborne of

Chester, and in the following year, on his recommendation,

supplemented his report with one from James Watt, who was just then

coming into repute through his improvements upon the steam-engine.

Golborne's opinion was that it was "extremely practicable" to deepen

the river up to the Broomielaw. By banking, straightening, and

dredging he thought it possible to secure a depth of six feet of

water there at neap tides and nine feet at spring tides, and the

cost he estimated at £8640 or perhaps £10,000 sterling. [Burgh

Records, 5th Jan. 1769.] Another Act of Parliament was then

obtained, and Golborne and his nephew were employed to proceed with

the work at a yearly salary of £220 sterling. [Ibid. 3rd Jan. 1771.]

Golborne's plan was to use the current of the river itself as far as

possible for the deepening of the channel. Thus the current at

Dumbuck Ford was to be thrown into a single channel instead of two,

and by means of jetties and banks the flow of the tides was made to

clear away the sand from the river bed. Golborne was afterwards

engaged to secure a channel six feet deep from Dumbuck lower beacon

to Longloch Point, [Ibid. 2nd Nov. 1772.] and so well were the city

fathers pleased with his work that they presented him with a silver

cup engraved with the city arms. [Ibid. 25th Oct. 1775. The cup cost

£35 8s.] Two months later, having ascertained by soundings that by

Golborne's labours the channel from the Broomielaw to Dumbuck had

been made actually seven feet ten inches deep, the Town Council, on

the suggestion of the Trades and the Merchants Houses, gave Golborne

a gratuity of £1500 sterling, with £100 to his nephew for

supervising the work. [Ibid, 10th Dec. 1775.]

Almost immediately, it is true, the

Town Council received complaints from Lord Blantyre and the burgh of

Renfrew of damage entailed by Golborne's labours. Lord Blantyre

complained that the jetties on each side of his ferry quay at

Erskine had brought about an accumulation of sand which prevented

the ferry boat approaching the quay, and the burgh of Renfrew

alleged that the works had hurt its salmon fishery in the river. But

his lordship was satisfied with the provision of thirty or forty

pontoon loads of stone for the lengthening of his ferry quay, and

Renfrew with a money payment which continues to be made annually

till the present day. [Ibid. 2nd and 20th March, 1777; 3rd July, 5th

Oct. 1787 ; 26th May, 1779. This was only the first of many claims

made by the Lords Blantyre against the deepeners of the Clyde (ibid.

16th June, 1784, etc.), 5th Feb. 1784.] A similar claim was made by

Paisley, a few years later, for the silting up of the mouth of the

Cart, and was satisfied with a payment of £150. These, however, were

insignificant drawbacks to the fact that the real and permanent

development of the great harbour of Glasgow had been begun on

practical lines. |