|

By a decree of the

Court of Four Burghs, which, according to the date given by Sir John

Skene, was held at Stirling on 12th October, 1405, it was ordained

that two or three sufficient burgesses of each of the "King's

burghs" upon the south side of the Water of Spey should appear

yearly at the burghal parliament to treat upon all things concerning

the commonweal of all the burghs and their liberties. If the date is

correct, and if the ordinance took effect, this may be regarded as

the first step in the process whereby the Curia Quatuor Buygorum was

merged in the Convention of Burghs ; but the time for clearing off

the obscurity with which the early history of the court is enveloped

has not yet been reached, and no record showing that the decree was

put into operation has been discovered. Whether in obedience to the

decree, burghs outside of the chosen four really sent commissioners

or not, it is curious to observe that the privilege of doing so was

not extended to burghs beyond the Spey, such as Inverness, Elgin and

the other towns situated in the province of Moray. At that time, six

years before the battle of Harlaw, a distinction still existed

between the districts within and those without the bounds of ancient

Scotia. No similar exclusion is noticed elsewhere,

and in an act of

parliament passed in 1487 commissioners of "all the burrowis, baith

south and north," were appointed to convene, yearly, to commune and

treat upon the welfare of merchants and common profit of the burghs.

But even before this date representatives of the burghs in general

seem to have been in the habit of meeting and adjusting their common

affairs. Thus, on 21st March, 1483-4, "the commissaris of burghis"

allocated upon the individual towns their shares of a national tax.

The names of the burghs subjected to this impost, situated "beyond

Forth," have been preserved, and these include Elgin, Forres,

Inverness and Nairn, all on the Moray side of the Spey.

Unfortunately there is no corresponding list of the taxed burghs on

the south side of the Forth, nor is there a list of such earlier

than 1535. In the Roll of that year Glasgow duly appears, showing

that at that time it bore its share of national taxation as a

constituent member of the Convention of Burghs. The minutes of the

Convention are not preserved previous to 1552, and at the meeting

held in that year Glasgow was represented by its provost and another

commissioner.

Opinions as to the

true dates of the capture at sea of Prince James and the death of

his father, King Robert III., have been somewhat conflicting in the

past, but it is now generally agreed that the former event took

place in February or March, 1405-6, and the latter on 4th April,

1406. In this connection it is satisfactory to note that in the

"Short Chronicle" inserted in the Register of the Bishopric, the

capture is stated to be 30th March and the "obit" 4th April, 1406.

King James was in the twelfth year of his age when he succeeded to

the throne, but from that time he was detained in England eighteen

years, and did not enter upon the personal rule of his kingdom till

1424. Meanwhile the government of the country remained in the hands

of the Duke of Albany till, on his death in 1420, it passed to his

son, Duke Murdoch, and national affairs were thus conducted much on

the same lines as they had been since the beginning of the second

Robert's reign. The first duke was virtual ruler of the kingdom for

nearly half a century. It was a period during which some of the

nobles embraced the opportunity of augmenting their estates at the

expense of the crown, a mode of aggrandizement which brought about

fearful reprisals when the day of reckoning arrived.

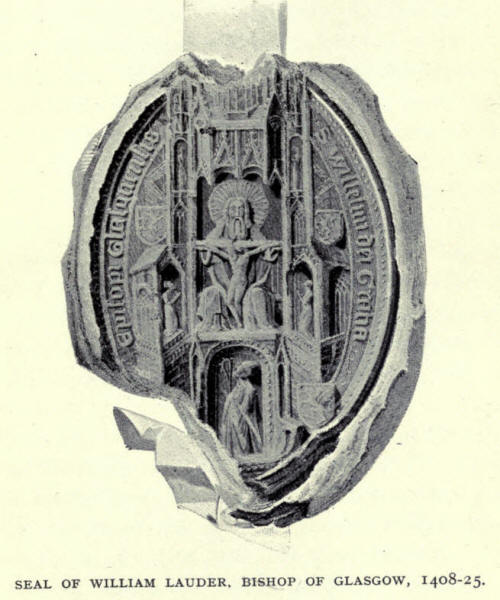

On the death of

Bishop Matthew, in 1408, the anti-pope, Benedict XIII., gave the

bishopric to William Lauder, Archdeacon of Lothian. The new bishop's

appointment was dated 9th July, 1408, and it is supposed that he

obtained consecration shortly afterwards, as, on 24th October

following, the English king gave a safe conduct to William Laweder,

bishop of Glasco, with 24 horsemen in company, to cross from France

and pass through England to Scotland." [Dowden's Bishops, p. 318;

Bain's Calendar, i, No. 773.] He seems not to have returned in time

to enter into possession of the temporalities till after Martinmas,

as in the account of the chamberlain of Scotland for 1408-9 credit

is given for the rents of the bishopric for the term of Whitsunday

and for the half of those falling due at Martinmas, 1408. The other

half of the Martinmas rents the chamberlain, by favour of the

bishop, expended in paying the fees of the bailies and sergeants,

and allowances were also given to certain kinsmen of the late

bishop. [Exchequer Rolls, iv. p. 99. The sheriff of Peebles had

collected £44, presumably at Stobo and Whitebarony, and the rents

collected in the shire of Lanark, within which were the two baronies

of Glasgow and Carstairs, amounted to £188 11s. 8d.]

Bishop Lauder's

progenitors belonged to an ancient family in the Merse. In a charter

granted at Lauder on 1st August, 1414, his father, there designated

"Robert de Lawedre," with consent of the bishop as his son and heir,

gave to the church of Glasgow two annual rents of twenty shillings

each, payable furth of tenements situated in Edinburgh, as an

endowment for anniversary services to be celebrated by the canons

and vicars of the cathedral. The charter was confirmed by the Duke

of Albany on 28th September; and on 19th May of the following year

Bishop Lauder gave specific directions for celebration of the obits

or anniversaries and for the tolling of the church bells and the

bell of St. Kentigern on the vigils of the services. [Reg. Episc.

No. 324, 326.]

The upper part of the

north-west tower of the cathedral, said to have been struck by

lightning and burned down in the time of Bishop Glendoning, was

restored by Bishop Lauder. The tower is known to have been vaulted

in stone, in the interior, at the junction of the new with the old

work. The vault rested on four corbels in the angles, curiously

carved with figures. Three of these corbels are now preserved in the

chapter-house and have been identified as part of the work of

restoration executed by Bishop Lauder. The bishop likewise placed

the traceried parapet upon the central tower. His coat of arms,

carved on the western side, is the earliest heraldic device in the

cathedral. The belfry stage of the tower is supposed to have been

erected by Cardinal Walter or by Bishop Glendoning, and the stone

spire, rising from Lauder's parapet, was constructed by Bishop

Cameron. The lower courses of this tower were obviously intended to

carry a stone structure to the top, and if timber was at any time

used here in constructing a spire that must have been regarded as a

temporary expedient. [Glasgow Cathedral (1901). p. 19; (1914). PP.

39, 40. Mr. Chalmers. states that Lauder's parapet was reconstructed

in 1756, in consequence of having been injured by lightning (Ib.).]

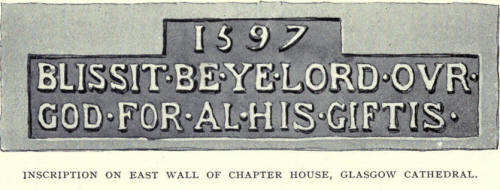

The masonry of the

chapter-house, begun in the thirteenth century, had remained very

much in its original condition for nearly 200 years, the foundation

walls showing little more than a mere outline of the building plan.

The erection of this building was also resumed by Bishop Lauder, who

made considerable progress with the work. His arms are carved on the

exterior of the west wall and also upon the cornice of the dean's

seat in the east wall, the latter accompanied with an inscription [WILMS:

FUDAT: ISTUT: CAPILM: DEI "óWillelmus fundavit istut capitulum Dei.

Doubts have been entertained whether this inscription applies to

William de Bondington who began the building or to William Lauder,

who carried it on, but the preponderance of opinion favours the

latter. prelate.] bearing that he had built the chapter-house, but

the completion of this work also he had to leave to his successor.

Bishop Lauder took an

active share in the administration of national affairs. He was one

of the commissioners appointed to treat with English representatives

for peace in 1411 and was one of the ambassadors who negotiated for

the return of the king in 1423. He was chancellor of the kingdom

from 1421 till his death in 1425.

The foundation of the

university of St. Andrews, in 1410, was an event of national

importance and must have attracted attention in all scholastic

circles throughout the country. In cathedrals at that time the

chancellors presided over those in their respective localities who

taught in letters, and the precentors or chantors looked after the

training of the young musicians. By the rule of Sarum, adopted in

Glasgow cathedral, it was directed that the chancellor should bestow

care in regulating the schools and repairing and correcting the

books, and that the

precentor should provide for the instruction and discipline of the

boys destined for service in the choir. Taking advantage of the

guidance thus provided, municipal authorities freely co-operated

with the cathedral dignitaries in the promotion of education within

their bounds, as in 1418, when the alderman and community of

Aberdeen nominated a master of the burgh schools and presented him

to the chancellor of the diocese for approval. Though it is not till

forty years later that we have documentary evidence of the

magistrates of Glasgow being associated with the Grammar School of

that city, it is known that such a school was in existence in 1460,

but as to its previous history no information is vouchsafed. Such

elementary education as could be gained at these schools would

afford the preparation necessary for the student entering a

university; but when this stage was reached he had no choice but to

leave the country and betake himself to other parts, perhaps to

Oxford or Cambridge, if peace existed between England and Scotland

at the time ; if not, the continent was the only resort. Latterly it

was Paris, where the Scots College had been founded by the Bishop of

Moray in 1326, that the Scottish students mainly frequented and

there at the close of the fourteenth and beginning of the fifteenth

century large numbers of them were yearly assembled. No doubt many

Scottish students embraced the opportunity of completing their

education at St. Andrews, though the older universities abroad still

continued to be frequented by those who could afford and preferred

that course ; but that the educational facilities obtainable at St.

Andrews were largely appreciated, and that there was a call for

extension of such accommodation in Scotland, is shown by the fact

that Glasgow, only forty years later, followed the example set by

St. Andrews and secured the establishment of a university of its

own.

One of the

transcripts supplied by Father Innes to Glasgow College was that of

a notarial instrument of some interest as showing the procedure in

the borrowing of money on heritable security in the beginning of the

fifteenth century. In presence of a notary public and witnesses,

Andrew of Kinglas, burgess of Glasgow, in consideration of the loan

of ten merks Scots, conveyed to William Johnson, another burgess, a

rood of waste land in the front, with a yard at the back, lying on

the east side of the street leading from the cathedral church to the

market cross, between the land of the heirs of John Bridin on the

south and the land of John Smith on the north. The property was to

be redeemable by the borrower on his repaying to the lender the ten

merks, with any sums profitably expended by him on the property, and

that at any Whitsunday, between the rising and the setting of the

sun, on the altar of the Virgin Mary in the cathedral church. [Reg.

Episc. No. 323 (7th November, 1413). The witnesses were Mr. John of

Mortoun, provost of the collegiate church of Bothwell; Sir Thomas

Merschel, perpetual vicar of the church of Kilbirny, in the diocese

of Glasgow; Adam Massoun, Nicholas of Prendergast and Andrew Smyth,

burgesses of the burgh of "Glasgu."] In such cases an altar became

so well established as the place of redemption that for some time

after the Reformation, when altars had been removed, it was

customary to specify as a substitute the place in the church where

the altar had stood. |