|

BY a series of

misfortunes in the last quarter of the thirteenth century, the

prosperous condition of Scotland was completely arrested, and for a

long time the story which the annalist has to tell is one of

overbearing oppression on the one side and of patriotic and

ultimately successful resistance on the other. Through the loss of

his children, two sons and a daughter, who all died within the years

1281-3, King Alexander III., when accidentally killed on 19th March,

1285-6, left as his successor to the Scottish throne an infant

grand-daughter, Margaret the Maid of Norway, who survived him for no

more than the short period of four years. On account of the divided

interests of the claimants to the crown, chiefly in consequence of

their landed estates being spread over both countries, and those

situated in England being held of King Edward as feudal superior,

that monarch's ambitious scheme for the union of the two kingdoms

was not devoid of Scottish support, and but for the patriotism of

some of the lesser barons and the feeling of sturdy independence

which pervaded large masses of the people, his purpose might have

been accomplished. During this critical period Glasgow must have had

its share of the country's prevailing troubles, and though many of

its citizens, barony men and churchmen, may have had their names

inscribed on the Ragman Roll, it is known that Robert Wischart, the

warrior bishop, was not without local followers in his valiant

contest for freedom.

Bishop Wischart was

appointed one of the guardians of Scotland after the death of King

Alexander, and throughout subsequent events, the interregnum of

1290-2, the inglorious reign of John Balliol, 1292-6, the

interregnum of 1296-1306, Wallace's protectorate and the early years

of Bruce's reign, the bishop took a prominent part in public

affairs. He was keenly patriotic,

[Though in the

elaborately formal record of proceedings which resulted in the

selection of John Balliol as king no express disavowal of Edward's

supremacy appears, independent chroniclers are not so reticent, and

paraphrasing their statements, Wyntoun, in a passage marked,

perhaps, more by poetical license than strict historical accuracy,

ascribes to Bishop Wischart delivery of this spirited protest:

"Excellend Prynce (he

sayd), and Kyng,

the ask ws ane unleffull thyng,

That is supery oryte;

We ken rycht noucht, quhat that suld be;

That is to say, off our kynryk,

The quhilk is in all fredome lik

Till ony rewme, that is mast fre,

In till all Crystyanyte,

Wndyr the sown is na kyngdome,

Than is Scotland, in mare fredome.

Off Scotland oure Kyng held evyr his state

Off God hym-selff immedyate,

And off nane othir mene persowne.

Thare is nane dedlyke king with crowne,

That ourlard till oure Kyng suld be

In till superyoryte."

Wyntoun's Chronicle

(Historians of Scotland), book viii. ch. v. p. 301, lines 821-36.

Some words in the quotation may be glossed thus: "unleffull" -

unlawful; "We ken," etc.—we well know that should not be; "kynryk" —

country; "rewme"—realm; "sown"—sun; "mene"—mediate; "dedlyke"—mortal;

"ourlard"—overlord.]

and though, under

compulsion or urgent expediency, he swore allegiance to Edward, the

oath was broken as often as the opportunity occurred. [A list of

these occasions is given in Burton's History of Scotland, vol. ii.

pp. 260-1.] As Cosmo Innes has observed, it was a time when strong

oppression on the one side made the other almost forget the laws of

good faith and humanity. The bishop was a friend and supporter of

Wallace, and having joined the army gathered under Bruce and others,

was among those who surrendered and made " peace " at Irvine in

July, 1297. [Bain's Calendar, ii. Nos. 907-10.]

To about this time

may be assigned the encounter known as the battle of the Bell o' the

Brae. An animated passage in the metrical narrative of Harry the

iinstrel describes how Wallace overcame a body of English troops in

the streets of Glasgow. The story is circumstantially told and

vouched by the expression "as weyll witnes the buk," suggesting that

the minstrel was proceeding on something more substantial than oral

tradition. Starting from Ayr one evening, Wallace and his band rode

"to Glaskow bryg, that byggit was of tre," which they reached next

morning at nine. Here the attacking party was formed into two

divisions. One division, under thelaird of Auchinleck, "for he the

pasage kend," made a detour, and seems to have crossed the Clyde

above the town, while the other division, headed by Wallace, marched

up the "playne streyt" leading to the castle, and attacked the

garrison in front. Then at the opportune moment Auchinleck's

division rushed in by "the north-east raw" (i.e. the modern Drygait),

" and partyt Sotheron rycht sodeynly in twyn." Thus pressed in front

and surprised in rear, the garrison forces were completely routed,

and fled to Bothwell, there joining another English army, who

checked the further pursuit of Wallace and his men. The retreat is

thus described:-

"Out off the gait the

byschope Beik thai lede,

For than thaim thocht it was no tyme to bide,

By the Frer Kyrk, til a wode fast besyde.

In that forest, forsuth, thai taryit nocht;

On fresche horss to Bothwell sone thai socht.

Wallace followed with worthie men and wicht."

[The Wallace, book vii. lines 515-616.]

At that time, the

open ground east of the Blackfriars' Kirk and the woods and fields

beyond, would afford the readiest route in the retreat to Bothwell.

The narrative is true to the locality in its outstanding features;

and, keeping in mind that Wallace, from his early days, was well

acquainted with the district, that he had the co-operation of the

bishop, and was on intimate terms with his co-patriots, the monks of

Paisley, [See The Abbey of Paisley, by Dr. J. Cameron Lees (1878),

chap. x. As a reward for the patriotism of the monks during the wars

of Wallace and Bruce. the English burned their monastery in 1307

(Glasgow Memorials, pp. 28, 29).] who had dwellings and dependents

in Glasgow, and that these dependents had the opportunity of knowing

and communicating to Wallace the most favourable time and place of

attack, it would have been strange if some attempt had not been made

to molest the English garrison. Notwithstanding the absence of

notice in the scant remains of contemporary chronicles, and though

some of the details are erroneous or exaggerated, there is reason to

believe that the account of the battle of the "Bell o' the Brae" was

founded on a real incident in the career of our national hero.

Bothwell, situated

about eight miles south-east of Glasgow, to which the vanquished

remnant fled, was long the headquarters of the English armies in

Clydesdale. Bothwell castle, while occupied by the English towards

the end of the thirteenth century, stood out a siege by the Scots

for more than a year, but the garrison were at last starved into

submissions. [Bain's Calendar, ii. Nos. 1093, 1867.] From that time

the castle seems to have been held by the Scots till retaken by the

English in the autumn of 1301. During part of the time occupied by

the latter siege, King Edward was in the vicinity and doubtless took

an active part in directing operations. On 12th August, while the

besiegers were still busy, he granted to Aymer de Valence the castle

and barony of Bothwell, and all other lands which William de Moray

had forfeited through his patriotism. In August Edward was in

Glasgow, and took the opportunity of making devout oblations at the

local shrines and altars. Offerings were made on the 20th of the

month at the shrine of St. Kentigern; on the following day at the

high altar and at the shrine; on the 24th in his own portable

chapel, in honour of St. Bartholomew (whose day it was) ; again on

25th in his chapel, this last being a special offering on account of

good news of the capture of Sir Malcolm Drummond. The king's

oblations, costing in money seven shillings each, were continued in

September, an offering having been made on the 2nd of that month in

his portable chapel; on the 3rd at the shrine of St. Kentigern; and

on the 23rd at the high altar and at the tomb of St. Kentigern. The

tomb is expressly described as being situated " in volta," meaning

apparently the crypt of the cathedral. On 6th September the sum of

six shillings was given to the Friars Preachers as a contribution

towards their food supply.

For prosecuting the

siege of Bothwell Castle supplies of material were forwarded from

Glasgow. In August timber was obtained from the neighbouring woods

for the construction of a siege engine, brushwood was collected for

hurdles to form a bridge, and night watchmen were employed to guard

the implements and stores. Waggons were hired at Glasgow for

carriage of the engine to Bothwell. Purchases of coal, iron, and

tools were made at Glasgow, both during and after the siege, the

implements so procured including anvils, hammers, chisels, nails,

picks, shovels, an axe, a ploughshare, a grindstone, a cauldron,

coffers and locks. Congratulations on the surrender of the castle

were transmitted to Edward on 2nd October, by which time he had

apparently left the district. [Bain's Calendar, ii. and iv.; Rhind

Lectures (1900), "The Edwards in Scotland," pp. 35, 36; Reg. Episc.

p. xxxiii. Edward's usual offering of seven shillings was equal to

about five guineas of the present day.]

Notwithstanding the

siege and similar successes Edward was experiencing the difficulty

of keeping the Scots under control, for no sooner had he secured

submission in one district than trouble broke out elsewhere, and in

this spasmodic warfare both Bishop Wischart and the men of the

barony had their share. In August, 1302, Pope Boniface VIII. wrote

the bishop expressing astonishment that, as reported, he had been

the "prime instigator and promoter of the fatal disputes which

prevailed between the Scottish nation and King Edward," and calling

upon him, by earnest endeavour after peace, to obtain forgiveness. [Hailes'

Annals, 3rd edition, i p. 330.] This appeal had no immediate effect

on the bishop's course of action, and in 1302-3 he was treated as a

rebel, his estates were forfeited and parts of his lands in Glasgow

barony were laid waste. Even Edward's collector could not get

certain sums from the "farm of the burgh of Glasgow, because the

tenants were destroyed by the Irish," apparently alluding to the

Irish foot soldiers who formed a large section of the English army.

There was also a deficiency in the barony collection, as

distinguished from that of the burgh, because so much "land of the

barony lay waste." [Bain's Calendar, ii. p. 424.] The burgesses of

Rutherglen, also, took the opportunity of discontinuing payment of

tolls on their goods bought or sold in Glasgow. [Antea, p. 100.]

In consequence of

Edward's energetic campaign of 1303, and the apparent hopelessness

of further resistance, the bishop again became reconciled to Edward

[In or about January, 1303-4, Edward had stated the conditions for

receiving the bishop of Glasgow, William le Waleys, Sir David de

Graham, Sir Alexander de Lindesey and Sir John Comyn (Bain's

Calendar, ii. No. 1444).] and besought him to authorise the levying

of tolls, as formerly, and to confirm the charters of the church,

that he and his clergy might be paid their arrears. [Bain's

Calendar, ii. No. 1626-7.] That the desired restoration of

temporalities was conceded may be inferred from a letter dated 10th

April, 1304, in which Edward thanked the bishop, "dearly," for

giving the prebend of Old Roxburgh to his (the king's) clerk who was

about to be sent out of the country on special business, thus making

it desirable that he should obtain immediate possession. [Ib. No.

1502. ] In August, also, the bishop and chapter were in a position

to give to the Friars Preachers the Meadow-well in Deanside, the

water of which was to be led to their cloister. [Antea, p. 117.]

The friendly attitude

thus subsisting between King Edward and the bishop was not long

maintained. Sir William Wallace having been betrayed into Edward's

hands had met his death in London in August, 1305. According to

Blind Harry, the place of capture was Robrastoun or Robroystoun,

[Book xi. lines 997, 1083.] situated in the barony, about four miles

north-east from Glasgow Cross ; but some chroniclers, including

Walter Bower, assert that Wallace was seized "at Glasgow," which,

taken literally, would mean in the city itself. [Pictorial History

of Scotland, i. pp. 776-7. John Major, in his History of Greater

Britain, published in 1521, when he was principal Regent of the

University, says that, "by a shameful stratagem, Wallace was seized

in the city of Glasgow" (Scottish History Society edition, p. 203).]

The actual place of capture is accordingly doubtful, but all

accounts agree in crediting Sir John Monteith, governor of the

castle of Dumbarton, with the chief part in the transaction. At this

stage King Edward, deeming that Scotland was finally at his

disposal, proceeded to supply it with a constitution, and an

"Ordinance for the settlement of Scotland" was drawn up to his

satisfaction. [Bain's Calendar, ii. No. 1691-2.] But before six

months had elapsed the scheme became utterly inoperative, and the

English king had virtually to recommence the work of conquest. In

the spring of 1305-6 Robert Bruce took the field and forthwith the

irrepressible bishop joined his standard, and it is said that from

vestments in the cathedral he prepared the robes and royal banner

for the coronation. Exasperated at this turn of affairs Edward, on

26th May, 1306, issued his commands for taking the most effectual

means for seizing the bishop and sending him to the king. Shortly

afterwards came the announcement that Wischart had been taken

prisoner at the siege of Cupar castle, news which elicited

from Edward the

avowal that he was almost as much pleased with the capture of the

bishop as if it had been that of the Earl of Carrick. [Bain's

Calendar, Nos. 1777, 1780, 1786.]

The forfeiture of the

bishop's interest in the temporalities of his see, which followed

this new rupture, afforded an opportunity of bestowing on Wallace's

captors part of their reward. It had been arranged that 40 merks

should be given to the valet who spied Wallace, that 6o merks should

be divided among those who assisted at his seizure, and that land of

the yearly value of £100 should be assigned to Monteith. [Palgrave's

Illustrations, p. 295; Wallace Papers, No. XX.; as cited in Burns'

Scottish Way of Independence, ii. p. 134.] In part fulfilment,

apparently, of the last of these grants, King Edward, on 16th June,

1306, instructed Aymer de Valence to give to Sir John de Meneteth

the "temporality of the bishopric of Glasgow, towards Dumbarton";

but seeing that in course of time the revenues of the see would

require to be applied to their legitimate uses, Sir John's

possession was only to last during the king's pleasure. [Bain's

Calendar, ii. No. 1785.] It is likely enough that the portion of the

temporality vaguely described as "towards Dumbarton" consisted of

the clearly defined area of the barony lands lying on the Dumbarton

side of the Clyde and west side of the river Kelvin. These lands,

including the " toune of Partik," were valued at £74 12s. 4d. old

extent.

Bishop Wischart was

removed to England and there kept in strict confinement for many

years. While he was a prisoner in Porchester Castle, near

Portsmouth, the Scottish king, Robert the Bruce, restored to him his

churches, lands and possessions. This was done by a charter dated

26th April, 1309, in which sympathetic reference was made to "the

imprisonments and bonds, persecutions and afflictions which a

reverend father, lord Robert, by the grace of God, bishop of

Glasgow, has up to this time constantly borne, and yet patiently

bears for the rights of the church and our kingdom of Scotland." [Glasg.

Chart. i. pt. ii. p. 21.] But, unfortunately, formal concessions of

this sort were of no avail in procuring relief to the unhappy

victim, and efforts in other directions for his release were

likewise futile. With the view of thwarting applications to Rome for

help, King Edward II., on 4th December, 1308, represented to the

pope that the crimes, lese-majesty, and other offences of the bishop

of Glasgow against the late king and himself, forbade any hope that

he could be allowed to return to Scotland. [Bain's Calendar, iii.

No. 61.] Two years later, Edward, hearing that the bishop, "who has

sown such dissensions and discord in Scotland," was busy suing for

his deliverance at the court of Rome, with "leave to return to his

own country, which would be most prejudicial to the king's affairs

there, and an encouragement to his enemies," the English chancellor

was instructed to concert measures for opposing the bishop's

restoration either to his office or his country, " pointing out his

evil conditions and his oaths repeatedly broken, and anything else

to induce the pope to refuse him leave even to return to Scotland."

[Ibid. No. 194. ] After being summoned before the pope to answer for

his offences against Edward I., he was sent back to England in

November, 1313, "to be detained by the king at pleasure, till

Scotland was recovered," [Ibid. No. 342.] but following upon the

military and political events of the following year, the final

liberation of the bishop was secured. By that time, however, he had

become blind, and he survived his long hoped-for deliverance only

two years. He died on 26th November, 1316, and was buried in the

crypt of the cathedral between the altars of St. Peter and St.

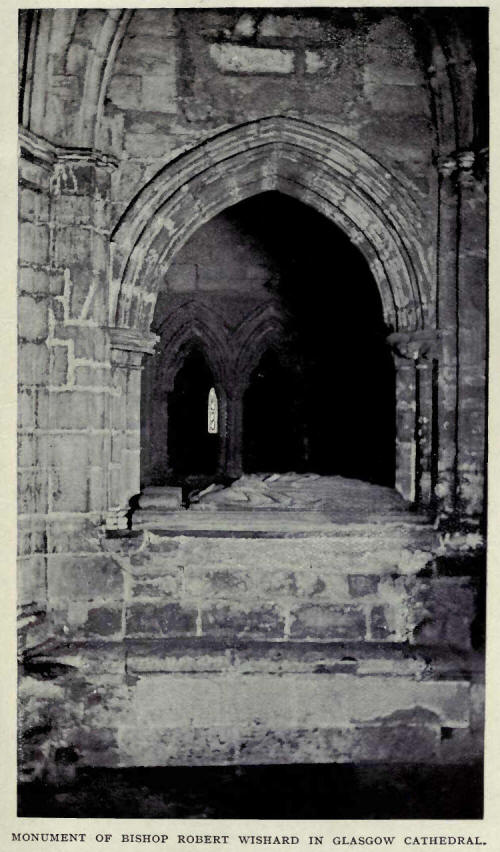

Andrew. A dilapidated effigy now lying in the open arch of one of

the cross walls, at the east end of the crypt, is supposed to have

once covered his tomb. [Book of Glasgow Cathedral, pp. 412-3;

Mediaeval Glasgow, pp. 58, 59.]

|