|

IN the first volume of this history

occasional reference has been made to the early schools of Glasgow.

These schools were probably of more importance in the life of the

community than the casual mention in the various early records might

seem to imply. The Rule of Sarum, or Salisbury, which was adopted as

the ritual of the Glasgow bishopric almost from its restoration in

the twelfth century, ordained that the chancellor should regulate

schools and the precentor provide for the instruction and discipline

of the boys serving in the choir. [Regist. Epis. Glasg. i. 270, No.

211.] Abundant evidence exists in the early Scottish chartularies of

the provision of schools by the clergy throughout the country as

early as the twelfth century itself. [Charters and Documents, i. 44;

Grant's History of the Burgh and Parish Schools of Scotland.]

In connection with Glasgow Cathedral

there must have existed from the very first a song school for the

musical instruction of the boy singers of the choir. Its location

was probably at the hall of the vicars choral on the north side of

the cathedral, from which Vicars' Alley, the passage between the

Royal Infirmary and the graveyard of the cathedral, still takes its

name. ["Hall of the Vicars Choral," by Archbishop Eyre, in The Book

of Glasgow Cathedral.] Among other references to this song school

there is the deed by which, in 1539, John Panter, "formerly

preceptor of the song school of the metropolitan church of Glasgow,"

settled certain rents of a tenement and yard on the east side of

Castle Street on the master of the cathedral song school and others

for the performance of anniversary services at certain altars.

[Charters and Documents, ii. Appendix, No. xxi.] Under the various

Acts which followed the Reformation, the revenues of the Vicars

Choral were transferred to the provost and bailies of Glasgow, the

need for training boys in the elaborate Latin services of the

cathedral came to an end, and the song school of the metropolitan

church ceased to exist. Accordingly, in 1590 John Panter's nephew,

Sir Mark Jamieson, life-renter of the tenement above mentioned, went

to the Tolbooth and delivered to the provost and bailies the

documents of his uncle's gift " in ane litill box, to be keipit in

the commoun kist." [Glasgow Burgh Records, i. 155.] The cathedral

song school had served its time, and had laid the foundations of a

musical taste in Glasgow and its cathedral which has never since

died out.

Meanwhile, at a much later date, a

second song school had been founded in the city. When the Church of

St. Mary of Loretto and her mother St. Anne, now the Tron church,

founded by James Houstoun, vicar of Eastwood and sub-dean of the

cathedral, in 1525, [Charters and Documents, ii. pp. 494-7.] grew

into a collegiate foundation, the magistrates and council endowed it

with sixteen acres of the Gallowmuir and nominated the third

prebendary, whose duties were to have charge of the organ and to

carry on a song school. [Lib. Coll. pp. xv.-xxv.] After the

Reformation the Trongate church and churchyard were sold by the

bailies and council, but it says much for their good taste and

enlightenment that they carried on this school as long as they

could. In the deed of 1570, conveying the church and churchyard to

James Fleming, "the common school called the Song School," standing

immediately to the west of it, is not included. [Charters and

Documents, i. pt. ii. pp. 140-142.] The Town Council seems to have

gone still further, and to have accepted some responsibility for

carrying on the school. Towards the support of the teacher, one

Thomas Craig, in 1575, the "burgess fines," or entry money of a new

freeman, John Cumming, were assigned—a somewhat frequent method of

making payments at that time. [Burgh Records, p. 43.] A few days

earlier the town's accounts show a payment to Thomas Craig, of

twenty-three shillings for straw and thatching of the "New Kirk

scule." [Burgh Records, 457.] Three years later, in February, 1578,

appears a payment of ten pounds "to Thomas Craig for his support in

teicheing of the new kirk scole." [Burgh Records, 465.] In June,

1583, again, occur payments—forty shillings "to Mr. William

Struthers for to pay the maul (or rent) of ane sang scole," and

eight pounds "gewin to Thomas Craig, maister of the Tronegait scole,

for his chaplainrie." [Burgh Records, i. 472.] In 1588, however, the

town council found itself in money difficulties. To meet these it

decided on feuing certain of its common lands and other properties,

Among these last was "the scuile sumtyme callit the Sang Scuile."

[Burgh Records, i. 125.] It does not appear, however, that the

school was actually sold, and eleven years later there is a record

of a burgess fine being given "to Johne Craig scholemaister for his

service done be him." [Burgh Records, i. 187.] It seems likely that

the school had been removed to new premises, for payments of forty

shillings are recorded in 1577 and 1583 for the rent of a chamber

"to be ane sang scole." [Burgh Records, i. 462, 472,] In 1626 the

council made an agreement with James Sanders to give instruction in

music to all the children of the burgh who might be put to his

school for a salary of ten shillings a quarter to himself and forty

pennies to his man, and at the same time forbade all others to teach

music in the burgh. [Burgh Records, i. 354.]

At a salary like that it is evident

that the music school master must have had other means of

livelihood. In the next entry regarding the Song School, twelve

years later, Sanders is mentioned as "reader," so it may be gathered

that the pre-Reformation office of the third prebendary of St.

Mary's, who was appointed by the magistrates, and whose duties were

to have charge of the organ and to carry on a song school, had been

perpetuated in a readership in the Tron kirk with the same musical

duties attached.

The entry alluded to, on 5th May,

1638, sets forth that the music school within the burgh was

altogether decayed, "to the grait discredit of this citie and

discontentment of sindrie honest men within the same who hes bairnes

whom they wold have instructit in that art." The magistrates

accordingly called Sanders before them, and with his consent

appointed Duncan Burnet to "take up the said school again." [Burgh

Records, i. 388.]

Still later, in 1646, the town

council engaged John Cant at a salary of £40 per annum for five

years to raise the psalms in the High Kirk on the Sabbath and in the

Blackfriars at the weekly sermons, "and for keeping ane music

school." [Burgh Records, ii. 96.]

These facts should be enough to show

that, whatever may have been the effects of the Reformation in other

parts of the country in killing and discrediting love of the fine

arts, the art of music at any rate continued to find approval and

substantial support from the magistrates and the people of Glasgow.

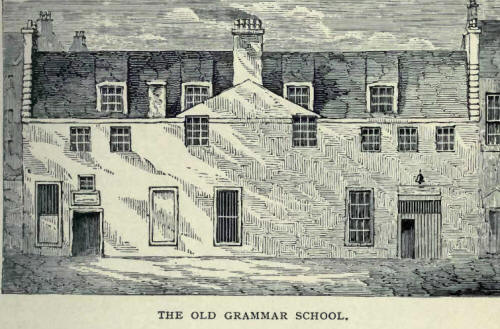

Equally creditable is the support

which appears to have been given from very early times to the

maintenance of a grammar school in the burgh. It is true that the

first reference to that Grammar School occurs only in 146o, but

there is every likelihood that, as enjoined on the chapter of the

cathedral by the ritual of Sarum, the school had been set up before

the close of the twelfth century. Bishop Jocelyn, the energetic and

enlightened prelate who began the building of the present cathedral

in 1175, and secured from William the Lion the charter of a burgh

and a fair for his episcopal city of Glasgow, set his seal, in the

year ii8o, to the deed confirming the Abbot of Kelso in possession

of the churches and schools of Roxburgh, and was not in the least

likely to overlook the duty and the advantages of setting up a

grammar school in his own new burgh on Clydeside. When the Grammar

School of Glasgow is first referred to, in 1460, it was already a

long established institution. It is notable that the deed by which

Simon Dalgleish, precentor and official of Glasgow, conveyed to

Master Alexander Galbraith, rector and master of the school, and his

successors, a tenement on the west side of the Meikle Wynd, or High

Street, to be held by the master and scholars for certain religious

services, declared that the provost, bailies, and councillors of the

burgh were to be patrons, governors, and defenders of the gift.

[Glasgow Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. p. 436.] It does not

seem likely that this was the first official connection of the town

council with the school; but real authority in appointing and

dismissing the master of the school still lay with the chancellor of

the cathedral. In its well-known judgment of 1494, the chapter of

the bishopric solemnly declared that Master Martin Wan, the

chancellor, and his predecessors of the church of Glasgow, had been,

without interruption and beyond the memory of man, in peaceable

possession of the appointing and removing of the master of the

grammar school, and of that school's oversight and government, and

further, that it was unlawful, without the chancellor's permission,

to keep a grammar school in the town; and accordingly that "a

certain discreet man," Master David Dun, presbyter of the diocese,

who had set himself to teach youths grammar and the elements of

learning within the city, had no right to do so, and accordingly

must be "put down to silence in the premises for ever." [Charters

and Documents, i. 89, No. xl.]

The magistrates nevertheless made

certain claims. In 1508, when Mr. Martin Rede, then chancellor,

appointed Mr. John Rede to be master, the provost, Sir John Stewart

of Minto, and others, protested and claimed for the magistrates the

right to admit Mr. John and the other masters of the schools. The

matter was decided by reference to the foundation and letters of Mr.

Simon Dalgleish in 1460. [Diocesan Registers, i. 427, ii. 267.]

For his stipend the master of the

Grammar School seems to have had to look, not to any direct

remuneration for the work of teaching, but, after the manner of the

church of that time, to the revenues of some other office. In

connection with St. Ninian's leper hospital at the south end of

Glasgow bridge, William Stewart, a canon of the cathedral, had built

a chapel near it at the corner of Rutherglen Loan, and in 1494 he

endowed it with certain annual rents and a tenement on the south

side of the Briggate. At that time the chaplain was the master of

the Grammar School, and from certain provisions it appears to have

been intended that the two offices should be held in perpetuity by

the same individual. [Reg. Epis. Glasg. No. 469.]

Further, on 8th January, 1572-73,

when the Provost and town council made over to the University all

the kirk livings which had been bestowed on the burgh by Queen Mary

in 1566, they specially exempted the chaplainry of All Hallows or

All Saints " granted formerly by us to the master of the Grammar

School," and ordained that it should remain for ever with him and

his successors. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. P. 161.]

Stimulated perhaps by the kindly

interest of the town council, the attendance at the school appears

to have increased, for in 1577 Robert Hutcheson and his wife

renounced their right to a house and yard on the west of the school

in order that these might provide more accommodation. [Charters and

Documents, i. pt. ii. P. 447.] At the same time the town's master of

works was instructed to " mak the grammar scole wattirfast, and at

the spring of the yeir to mend the west parte thairof." [Burgh

Records, i. 64.] On 16th November the accounts show a payment of

48s. "for XII threif of quheit straye to theik the Grammer Scole,"

and on 12th May following one of £8 "gevin to James Fleming, maister

of work to mend the grammar scole." [Burgh Records, i. 465, 466.]

The first actual record of the

appointment of a master by the town council occurs in 1582. On 13th

November Mr. Patrick Sharp, master of the grammar school, appeared

before the council and resigned his office, along with the

chaplainry of All Hallows altar and all other rents and duties

belonging to it, and the provost and council instantly, with advice

of the regents of the University, elected Mr. John Blackburn to the

mastership and chaplainry. [Burgh Records, i. 99.]

Blackburn proved to be an energetic

manager. Money evidently was needed, and he approached the town

council with the proposal that the front schoolhouse and yard should

be sold. He offered to pay the council a hundred merks and odds if

they would allow him to sell the property; or, alternatively, he

offered to accept two hundred merks for his consent that they should

dispose of it. In the end they agreed to pay him two hundred and ten

merks, and, this being agreed to, they sent round the drum on three

several days, as was customary, to advertise the sale, and finally

disposed of the property to Bailie Hector Stewart, the highest

bidder, for four hundred and seventy merks and an annual payment of

five merks. [Burgh Records, i. 176, 177, 178.]

Four years later drastic action had

to be taken with the schoolhouse itself. First the council appointed

a committee to visit and report on the repairs required. [Burgh

Records, i. 208.] The committee reported the school to be altogether

ruinous. The minute of 23rd August, 1600, contains a fine outburst

of generous sentiment: "It is condiscendit be the provest, bailleis,

and counsale that thai think na thing mair profitabill, first to the

glory of God, nixt the weill of the towne, to have ane Grammer

Schole." Then as always, however, Glasgow was prepared to back its

sentiments with solid deeds, and the council gave order that "the

haill stanes of the rwinus dekayit fallin dovne bak almonshous

pertenyng to the towne" should be devoted to the rebuilding of the

school, and that Blackburn should report every council day on the

progress of the work. [Burgh Records, i. 210.] Money was required

for the job, and Blackburn was authorized to pay to the master of

works for the purpose four hundred merks, of the legacy left by "Hary

the porter" of the college. [Burgh Records, i. 217.] Other funds

were got from the feuing of the common lands, while £800 were raised

by means of a tax. [Burgh Records, i. 218.]

In the midst of the enterprise

Blackburn received a call to the ministry of a kirk in some other

part of the country. Reluctant to lose him, "that is and hes bein

ane guid and sufficient member in instructing of the barnes of the

towne and vther effaires of the kirk thairinto," the council

appointed two members to see the presbytery, and promise Blackburn

any "benefit " about the town when it should happen to fall vacant,

in order that he should be retained as master of the school. [Burgh

Records, i. 226.] These persuasive efforts were successful, and four

years later we find the council dealing with a certain Robert Brown,

gardener, for delay in paying to Blackburn "sax pundis money" for

the Martinmas term's rent of the All Hallows chaplainry due from .a

house and yard he occupied, belonging to "ane noble and potent Lord

Hew erll of Egglingtoune." [Burgh Records, i. 343.] A year later

still, in 1606, it became evident that among the "benefits"

conferred on the schoolmaster to induce him to remain in the town

must have been a certain number of burgess "fines" or dues. William

Balloch, maltman, is made burgess and freeman of the burgh as "one

of Master John Blackburn's burgesses granted to him by the provost

and baffles of the burgh for his service in the Grammar School."

[Burgh Records, i. 246.] By and by this source of revenue appears to

have been interfered with by an ordinance declaring that burgesses

were no longer to be admitted in favour of any person by reason of

his office, but only by the dean of guild. Blackburn complained that

this meant an annual loss to him of two burgess fines, and requested

that the loss be made good by a payment from the burgh treasury. As

an equivalent he was granted a yearly sum of forty merks. [Burgh

Records, i. 310.]

In 1611 it was arranged to feu

further ground belonging to the Grammar School, and Blackburn,

appearing before the council, very adroitly declared that while he

believed the whole of the money thus obtained belonged by right to

himself, yet he would submit to the will of the city fathers in the

matter. After discussion it was decided that "the said maister John"

should have half the money, the other half being assigned to the use

of the town. [Burgh Records, i. 318, 319.]

Nothing more is recorded of Master

John Blackburn, but the town council continued to take a vital and

kindly interest in its Grammar School. In 1624 the accounts show a

payment of £80 to "Maister William Wallace, scholmaister." [Burgh

Records, i. 477.] The school must now have grown beyond the powers

of one man, however, for in 1629, with Wallace present, the council

deputed two city ministers, the Principal of the University, and

four, well-known citizens to visit the school and report, and four

months later we find other two individuals named as masters of the

Grammar School. The council ordered forty merks each to be paid to

John Hamilton and James Anderston, in that capacity "for helping the

ministers to preach in their absence at divers times." [Burgh

Records, i. 370, 372.] A year later the council recorded its

approval of the efforts of Wallace, who " hes thir divers yeiris by

past, sen his entrie thairto, exercet his office faithfullie and

treulie in training of all scholleris putt under his chairge," and

they therefore earnestly requested and desired him to renew his

engagement with them. [Burgh Records, i. 376.] Eight years later

still, in 1638, it was ordered that he be paid all the rents due to

him out of the "hous of manufactorie" and that the burgh officers

help him to collect the rest of the dues belonging to him as master

of the Grammar School. [Burgh Records, i. 391.]

At that time the school and the town

evidently suffered from a certain looseness in the management of

their affairs. In 1639 the attention of the council was drawn to the

fact that small rents due to the town and school from a number of

houses, barns, and kilns in the city had gone out of use of payment,

and that others were likely to follow. It was therefore ordained

that such rent and dues should be engrossed by the town clerk in all

future sasines. [Burgh Records, i. 397.]

After the abolition of episcopacy by

the famous General Assembly held in Glasgow Cathedral in 1638, an

effort was made to secure a competent allowance out of the revenues

of the bishopric for the maintenance of the High Kirk, the Bishop's

Hospital, and the Grammar School. [Burgh Records, i. 431.] For these

purposes King Charles I. actually signed a deed by which the teinds

of Glasgow, Drymen, Dryfesdale, Cambusnethan, and Traquair were

handed over to the town. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. p.

480.] This deed was ratified by Act of Parliament, but was rescinded

in 1662 after the Restoration of Charles II. and episcopacy. [Act.

Parl. Scot. vii. 372.]

As a token of the town council's

special interest in the Grammar School, the scholars were in 1648

appointed to sit every Sabbath day in the college seat of the

Blackfriars Kirk, which stood nearly opposite the school, on the

east side of High Street. [Burgh Records, ii. 156.]

The Grammar School was not, however,

the only school in Glasgow. In 1604 the presbytery complained of a

plurality of schools, and considered "the school taught by John

Buchanan and the Grammar School quite sufficient, and in 1639 the

town council ordained that nae mae Inglisch scoolles be keipit or

haldin within this brughe heirefter bot four only, with ane wrytting

schooll"; [Burgh Records, i. 397.] and though in 1658 the council

directed the bailies to inhibit "the womane that hes tackine vpe an

schole in the heid of the Salt Mercatt at hir awin hande," [Burgh

Records, 20th Feb.] two years later an order was made "to tak up the

names of all persounes, men or weomen, who keepes Scots Schooles

within the toune, and to report"; and three years afterwards no

fewer than fourteen persons, eight of them women, were permitted to

keep Scots schools, "they and their spouses, if they ony have,

keiping and attending the ordinances within the samyne." [Burgh

Records, 20th Oct. 1660 and 14th Nov. 1663.]

Altogether it does not seem that

Glasgow was at any time ill supplied with means of education for its

rising generations. |