|

THOUGH the University

of Glasgow had been founded with great acclaim in 1451, its fortunes

during the first hundred years of its existence do not appear to

have been too prosperous. John Major or Mair, who was its principal

Regent from 1518 to 1523, described it in his History, published in

1521, as "poorly endowed and not rich in scholars." By each of the

successive sovereigns, from James II. to Mary, it, with its regents

and students, was specially exempted from taxation. [Charters and

Documents, i. pt. ii. p. 118, No. 50.] In 1563, in the letter under

Queen Mary's privy seal, it is described as "rather the decay of a

university than an established foundation," its schools and chambers

being only partly built, and the provision for its poor bursars and

teachers having ceased. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. p. 129,

No. 58.] The young Queen of Scots was, in fact, the first to give

the struggling seat of learning in the west a helping hand. By the

letter just referred to, the enlightened young ruler founded

bursaries for five poor scholars and granted the convent and kirk of

the Blackfriars to the college, with thirteen acres of land, forty

merks of annual rent from various properties, and ten bolls of meal.

At the same time she intimated her intention to provide further for

the establishment in order that the liberal sciences might be taught

there as freely as in other colleges of the realm. Her desire was

that the bursaries should be called "bursaries of owre foundatione,"

and she hoped so to benefit the college that it "sal be reputit our

foundatioun in all tyme cuming." But the times which followed were

in the hands of the queen's enemies and detractors. The men who

benefited most by her gifts in Glasgow would have been the very last

to acknowledge that Mary Stewart could do any good thing. And for

the history of that period succeeding generations have trusted most

to the pens of her most bitter and ungenerous enemies, John Knox and

George Buchanan. One may look in vain through the Calendar of

Glasgow University to-day for any sign of Queen Mary bursaries and

other benefactions.

With an enlightened

zeal for which it has not always received credit the Town Council

next came to the help of the struggling University. In January,

1572-3, it conveyed to the college all the lands and church property

granted to the city by Queen Mary in 1566-7. In their charter the

Town Council laid down the constitution of the College. After

setting forth that, for lack of funds, the "Pedagoguy" had wellnigh

gone to ruin, and that, through excessive poverty, the pursuit of

learning had become utterly extinct, the magistrates declared that

"with the constant and oft-repeated exhortation, persuasion, advice,

and help of a much honoured man, Master Andrew Hay, rector of

Renfrew and vice-president and rector of our University of Glasgow,"

they "endowed, founded and erected the said college." This was to

consist of a Professor of Theology, who should be president or

principal, with the regents, who should teach Dialectics, Physics,

Ethics, Politics "the whole of Philosophy"—and twelve poor students.

The endowment was for the "support and daily provision of these

fifteen persons and their common servants." The appointment of the

Principal was to be for life or fault, but, at the will of the

Principal, the Rector, and the Dean of Faculty, the regents might be

removed every sixth year, "that is, when they have conducted two

classes completely through the curriculum; especially if they begin

to weary of their work, and do not apply themselves with sufficient

diligence to their duty." The twelve other poor persons were to be

"duly provided, maintained in meat and drink, College rooms and

bedrooms, and other easements, for the space of three and a half

years only, a time we deem sufficient for obtaining the master's

degree in the faculty of arts, according to the statutes of that

faculty." The Principal was to employ himself every day of the week

in reading and expounding the scriptures in the College pulpit, and

for remuneration was endowed with the vicarage of Colmonell with

forty merks, as well as twenty merks from the College funds, while

the stipend of each of the regents was to be "twenty pounds of good

money." The Principal was prohibited from residing anywhere except

within the College, and the regents were forbidden to "entangle

themselves" in any other business except that of their office. The

scholars were to live in community, eat together, and sleep within

the College, and week about they were to perform the duties of

janitor, read the Bible in the public hall, and give a short

discourse after supper on the Saturday. The College doors were to be

locked from 8 p.m. till 5 a.m. in winter and from 10 p.m. till 4

a.m. in summer. All who lived in the College and their servants were

to be free from ordinary jurisdiction, and from all tolls and

exactions. Twice a year the College was to be visited and its

accounts were to be audited. Finally, no one was to be admitted as a

student unless he made beforehand a pure and sincere confession of

faith and religion.

The twelve students

thus provided for by the municipality were not, of course, the only

students at the College. The city's deed of gift refers to "the

twelve poor scholars and the two regents and all students that

prosecute their studies in the College"; but all were to be equally

bound by the rules laid down. [Charters and Documents, pt. ii. p.

149 ; Act. Pan. iii. 487, V. 88 ; Stat. Acc. xxi. App. 20.]

On 26th January,

1572-3, this charter was ratified by the Regent Morton.

Notwithstanding the

city's generous gift, however, the College appears still to have

been but poorly provided for, and five years later, when James VI.

was ten years of age, the Regent Morton granted to it the rectory

and vicarage of the parish of Govan upon terms which amounted to a

new erection and foundation of the University. Under this new

foundation the Principal, to be appointed by the king, was to be

well versed in Holy Writ, and to act as Professor of Hebrew and

Syriac. On alternate days he was to lecture on these languages and

on Theology, and on Sundays was to preach to the people of Govan. If

he were absent for three nights from the College his place was to be

considered vacant. His salary was to be two hundred merks as

Principal and three chalders of corn as minister of Govan. Of the

three regents the first was to be Professor of Rhetoric and Greek,

the second of Dialects and Logic, with the elements of Arithmetic

and Geometry. Each of these two was to have a salary of fifty merks.

The third regent was to teach Physiology and the observation of

Nature, with Geography and Astronomy. In the absence of the

Principal he was to take his place, and his stipend was to be "fifty

pounds of our money yearly." The appointment and dismissal of the

regents was entrusted to the Principal, who himself in turn might be

dismissed if necessary by the Chancellor, Rector, and Dean of

Faculty. The charter also provided for the maintenance of four poor

students or bursars, who must be "gifted with excellent parts and

knowledge in the faculty of grammar." These were to be nominated by

the Earl of Morton and his heirs, and admitted by the Principal, who

was to see to it that "rich men were not admitted instead of poor,

nor drones feed upon the hive."

There was to be a

"steward or provisor," who was to collect the rents and purvey the

victuals, his accounts to be

entered in a book and

submitted daily to the Principal. His salary was to be twenty pounds

and his expenses, besides his keep in the College. The Principal's

servant and cook and a porter were also provided for, the two last

to have six merks apiece and their food.

Everyone admitted to

the College was to make profession of his faith once a year, for the

"discomfiting of the enemy of mankind," and the community was to

enjoy all immunities and privileges granted at any time to other

universities in the kingdom.

The wisdom of this

new constitution, with its checks and counterchecks, is believed to

have been owed to Andrew Hay, the Rector of that time. If the new

erection discarded the pre-Reformation idea of a University, and

substituted for it, as Cosmo Innes says, "a composite school, half

University, half Faculty of Arts," [Charters and Documents, pt. ii.

p. 168.] it had the inspiring support of a new and fervid faith, and

the advantage of a man of ripe and varied scholarship in the

Principal who was to give it a start. John Davidson had been

principal regent from 1556 till 1572, and had been succeeded by

Peter Blackburn for two years. But in 1574 the redoubtable and

learned Andrew Melville had been appointed Principal. Though a stern

and uncompromising insister upon every jot and tittle of the new

form of church government, he was "accomplished in all the learning

of the age, and far in advance of the scholars of Scotland." [Cosmo

Innes, Sketches of Early Scotch History, p. 225.]

Born in 1545,

Melville had received his early education at Montrose grammar school

under Pierre de Marsiliers, and at St. Mary's College, St. Andrews,

and had proceeded to Paris, where he studied Greek, oriental

languages, mathematics, and law, and came under the influence of

Peter Ramus. He had helped to defend Poitiers during the siege in

1568, and in the same year—the year of the Battle of Langside—had

been appointed Professor of Humanity at Geneva. Among those whom he

met were Beza, Joseph Scaliger, and Francis Hottoman. Returning to

Scotland in 1573, he was almost at once singled out by his

qualifications for the office of Principal at Glasgow University,

and entered upon his duties in the following year. The astonishing

range of his teaching may be gathered from the narrative of his

nephew, James Melville, who accompanied him to Glasgow, and was

himself afterwards a professor at St. Andrews and a moderator of the

General Assembly. "Sa," proceeds this recorder, "falling to wark

with a few number of capable heirars, sic as might be instructars of

vthers theretu, he teatched them the Greik grammer, the Dialectic of

Ramus, the Rhetoric of Taleus, with the practise therof in Greik and

Latin authors, namlie, Homer, Hesiod, Phocilides, Theognides,

Pythagoras, Isocrates, Pindarus, Virgill, Horace, Theocritus, etc.

From that he enterit to the Mathematiks, and teatched the Elements

of Euclid, the Arithmetic and Geometrie of Ramus, the Geographic of

Dionysius, the Tables of Honter, the Astrologic of Aratus. From that

to the Morall Philosophic; he teatched the Ethiks of Aristotle, the

Offices of Cicero, Aristotle de Virtutibus, Cicero's Paradoxes and

Tusculanes, Aristotle's Polytics, and certain of Platoes Dialoges.

From that to the Naturall Philosophic; he teatched the buiks of the

Physics, De Ortu, De Caelo, etc., also of Plato and Fernelius. With

this he ioynid the Historic, with the twa lights thereof,

Chronologic and Chirographic, out of Sleidan, Menarthes, and

Melancthon. And all this, by and attoure his awin ordinar

profession, the holie tonges and Theologic. He teatchit the Hebrew

grammar, first schortlie, and sync more accuratlie ; therefter the

Caldai and Syriac dialects, with the practise thereof in the Psalmes

and Warks of Solomon, David, Ezra, and Epistle to the Galates. He

past throw the haill Comoun Places of Theologie verie exactlie and

accuratlie ; also throw all the Auld and New Testament. And all this

in the space of six yeirs, during the quhilk he teatchit everie day

customablie twyse, Sabothe and vther day; with an ordinar conference

with sic as war present efter dennor and supper." [Mr. James

Melville's Diary, Bannatyne Club, p. 38.]

Melville's teaching

was certainly universal enough. Within two years it was famous

throughout Scotland and even further afield. Numbers who had

graduated at St. Andrews came to Glasgow and entered again as

students. So full were the classes that the rooms could not contain

them. Among the most constant hearers was Mr. Patrick Sharpe, master

of the Grammar School, who was wont to declare that he learned more

from Andrew Melville's table talk and jesting than from all the

books. Altogether, James Melville concludes, "there was na place in

Europe comparable to Glasgow for guid letters during these yeirs,

for a plentifull and guid chepe mercat of all kynd of langages,

artes, and sciences."

In addition to all

these labours Melville took a leading part in the organization of

the Scottish Church, and assisted in the reconstitution of Aberdeen

University in 1575, and the reformation of St. Andrews University in

1579. In 158o he was transferred to St. Andrews as Principal of St.

Mary's College, and there promoted the study of Aristotle and

created a taste for Greek literature. There in 1582 he was Moderator

of the General Assembly which excommunicated Archbishop Montgomerie.

From the time of his leaving Glasgow he was mostly concerned in the

political squabbles of the kirk against the court, and for four

years, from 1607 till 1611, was for his bitterness imprisoned in the

Tower, only to be released at the request of the Duc de Bouillon,

who wished to make him professor of theology at Sedan. He died there

in 1622. [McCrie's Life of Andrew Melville.]

Glasgow undoubtedly

had the benefit of Andrew Melville's best years, and his ability and

zeal appear to have set the reconstituted University on a path of

success and prosperity from which it has never turned back.

Some idea of the

scholarship which made Glasgow University famous in an age when

Greek was not yet a popular study may be learned from the article in

Bayle's Historical Dictionary on John Cameron, who at the age of

twenty left Glasgow for France in 1600. "On admira justement que

Bans un age si peu avance it parlat en Grec sur le champ avec la

meme facilite et avec la meme purete que d'autres en Latin." [Cosmo

Innes, Sketches of Early Scotch History, p. 228,]

On attaining his

majority in 1587, James VI. ratified and granted anew the various

gifts and privileges conferred upon the College of Glasgow during

his reign—the rectory and vicarage of Govan, the properties which

formerly belonged to friars, chaplainries, and altars within the

city, the customs of the tron, and the freedom from taxation.

[Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. No. 75 and No. 79.] Thirteen

years later, Archbishop James Beaton, who for forty years had been

an exile in France, had his "whole heritages and possessions" in

Scotland restored to him, as already mentioned, but the Act of

Parliament by which this was done expressly excepted " quhatsumevir

rentes and dueteis pertening to the College of Glasgow." [Ibid. i.

pt. ii. No. 86.]

To the same period

belongs the restoration to the University of its ancient treasure

and symbol of authority, the Mace. Presented by the first Rector,

Mr. David Cadyou, on the occasion of his re-election in 146o, this

fine piece of silver-work appears to have been in some danger from

the plundering propensities of the Reformers in 156o, and when

Archbishop Beaton made his hurried visit to Glasgow, to rescue the

church jewels and documents, it was entrusted to him by the Rector

of that year, Mr. James Balfour, Dean of Glasgow. In 1590 the

Principal of the University, Mr. Patrick Sharpe, secured its return,

and had it repaired and enlarged. Its original weight was 5 lb.

7¼oz., it now weighs 8 lb. 1oz. [Muniments Univ. Glasg. iii. 523.]

The arms it bears are those of Bishop Turnbull, founder of the

University; James II., who procured the Papal bull; Lord Hamilton,

who gave the first endowment; the Regent Morton, who restored the

college in 1577; and the City of Glasgow, within which it has its

seat.

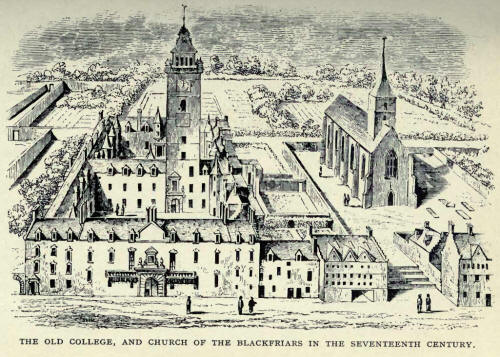

Much had been said of

the inconvenience and incompleteness of the old college buildings in

the High Street—the tenement acquired from Lord Hamilton in 1459,

the "place" or manor-house of Sir Thomas Arthurlee secured in 1475,

and the manse and "kirk room" of the Blackfriars granted by Queen

Mary in 1563, with the "schools and chambers standing half-built,"

which excited the benevolence of the brilliant young queen. But it

was not till 1632 that a beginning was made with the erection of new

buildings, and it was not till 1656 that the main part of these

buildings was completed. The eastern or back quadrangle, containing

the houses of the professors, still remained unfinished. Immediately

to the south of the college buildings the old chapel of the

Blackfriars, standing in its graveyard, was recognized as the

college chapel. A bird's-eye view of the buildings, previous to the

fire which destroyed the chapel in 1670, appeared in Captain

Slezer's Theatrum Scotiae, which was published in 1693. This shows

some of the old tenements then still standing on the street front to

the south of the new facade, with, between them, a wide passage

ascending by steps from the street to the graveyard, and away behind

college and kirk the spacious college gardens surrounded by hedges

and trees.

These college gardens

were not open to the students in general, but only to those who were

sons of noblemen, and who were accordingly allowed keys. [Munimenta,

ii. 421.]

Many of the students

lived in the college buildings, paying no rent for their rooms till

the year 1704, when a charge of four shillings to ten shillings per

session began to be made. [Munimenta Universitatis Glasguensis, iii.

513.] The occupants apparently furnished their own rooms, and some

of the townspeople seem to have made a business of hiring them the

furniture. Writing of his residence there in 1743, Jupiter Carlyle

says, "I had my lodging this session in a college room which I had

furnished for the session at a moderate rent. John Donaldson, a

college servant, lighted my fire and made my bed; and a maid from

the landlady who furnished the room came once a fortnight with clean

linens." [Autobiography of the Rev. Alex. Carlyle, D.D., p. 99.]

In 1594 certain

abuses seem to have excited the resentment of the citizens. It was

alleged that the rents, chaplainries, and other emoluments of the

Blackfriars kirk which had been assigned by the provost and bailies,

for the support of poor bursars in the college, were being wrongly

applied to the support of sons of the richest men in the town. The

provost and bailies took drastic action in the matter, withdrew

their gift of these rents and emoluments, and applied the revenues

to the support of the ministry within the city. Their action was

confirmed by act of parliament. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii.

No. lxxxi.]

Twenty years later

trouble arose over another source of the University's revenue. In

1581 Archbishop Boyd had mortified to the college the whole customs

of the Glasgow tron and market. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii.

No. lxxii.] In 1614, however, Archbishop Spottiswood, ignoring that

transaction, granted the town customs to the provost and burgh for a

yearly payment of a hundred merks. [Charters and Documents, i. pt.

ii. No. xcv.] The college authorities replied by feuing and

disponing to the provost and burgh the same customs and duties for

the ancient feu-duty of £50, being £16 13s. 4d. less than the

hundred merks demanded by the archbishop. [Charters and Documents, i.

ii. p. 466.] As the town had paid the archbishop a grassum of 4500

merks on his charter the provost and bailies naturally called upon

him to set the matter right. He thereupon gave them a bond

undertaking to procure a renunciation from the college of its claim

under the "pretendit gift" of Archbishop Boyd, or in default of this

to repay to them the grassum of 4500 merks. [Charters and Documents,

i. pt. ii. No. xcvi.] As sasine was granted to the town six months

later by the college authorities on their own charter it would

appear that Spottiswood had failed to make good his claim, and that

the burgh obtained the customs on the lower terms offered by the

college. [Charters and Documents, i. pt. ii. No. xcvii.] Thirteen

years later, in 1628, probably with a view to the avoidance of

similar contentions in future, the University obtained from

Spottiswood's successor, Archbishop Law, a charter confirming the

mortification of the tron dues by Archbishop Boyd in 1581. [Charters

and Documents, i. pt. ii. p. 471.]

Notwithstanding this

and other profits accruing to the town from the goodwill of the

University, the city fathers did not hesitate to take exception to

the ordinances of the college authorities. The sons of burgesses

enjoyed certain privileges and exemptions, mostly, it may be

supposed, living and taking their meals at home. Accordingly, on

18th November, 1626, complaint was made that the Principal and

regents had made an undue exaction on the town's bursars, "quha are

urgit to gif ane silver pund at their entrie." [Burgh Records, sub

die.]

King Charles I., in

1630, granted a charter under the Great Seal, confirming and

re-granting to the University all its properties and privileges,

under burden of the stipends to the ministers of Govan, Renfrew,

Kilbride, Dalziel, and Colmonell, whose revenues had been annexed to

the college. [Charters and Documents, No. civ.] The king also took a

personal interest in the affairs of the students and the University.

In 1634, with his own hand, he wrote to the archbishop requiring him

to see that the members of the college attended service in their

gowns in their proper pews in the cathedral.

Among other rights

claimed by the college authorities was that of exclusive and

complete jurisdiction, even in criminal matters, over the students.

Delinquents were rebuked, fined, and committed to durance in the

college tower for such offences as cutting the gown of another

student on the Lord's day, being found by the Principal "with a

sword girt about him in the toun," and sending a letter to the

Principal "conceived in very insolent terms." [Muniments, vol. ii.

p. 415.] In 1667 it was decreed that students found breaking the

college windows or otherwise damaging the buildings should be "furthwith

publicklie whipped and extruded the colledge." [Ibid. P. 340 ] And

for performing the practical joke of handing in the name of a fellow

student to be publicly prayed for in church, an act of uncalled-for

solicitude which became rather common for a time, a number of the

youths were summoned before the regents and severely reprimanded,

while one was expelled. [Ibid. ii. 373-379.]

On one occasion, on

18th August, 1670, the college authorities even proceeded to try a

student for murder. The court sat in "the laigh hall of the

universitie," with the rector, Sir William Fleming of Farme, as

president, and the Dean of Faculty and three regents as assessors.

In the indictment made by John Cumming, writer in Glasgow, elected

as procurator fiscal, and by Andrew Wright, nearest of kin to the

deceased, Robert Barton, a student, was charged with the murder of

Janet Wright in her own house, "by the shoot off ane gun," and the

punishment demanded was death. The accused pleaded not guilty, and

thereupon a jury of fifteen was impanelled and the trial proceeded.

Before pronouncing their

verdict the jury very

wisely demanded that the University should hold them scatheless of

any consequences, "in regaird they declaired the caice to be

singular, never haveing occurred in the aidge of befor to ther

knowledge, and the rights and priviledges of the universitie not

being produced to them to cleir ther priviledge for holding of

criminall courts, and to sitt and cognosce upon cryms of the lyke

natur." The court replied that, having agreed to "pase upon the said

inqueist in initio," the jury made this demand too late;

nevertheless, "for satisfactioune and ex abundante gratia," the

court undertook to hold them free "of all coast, danger, and

expenses." Whether or not the jury were completely satisfied with

this assurance we are not told, but their verdict was on the safe

side—Not Guilty. [Munimenta, ii. 340.]

Still later, in 1711,

when some of the students who had been making trouble in the city

were arrested, tried by the magistrates, and compelled to pay a

fine, the University authorities demanded the repayment of the

fines, declaring that the magistrates, if they refused, would be

held liable, " for all expenses and damadges that the said Masters

of the University may be putt to in vindicating their right and

jurisdiction over any of the scholars committed to their charge."

[Ibid. ii. 400.] The upshot is unknown.

Meanwhile the

functions of the college and the kirk were gradually being

separated. In 1621, by an Act of the Archbishop of Glasgow the

Principal of the University was relieved from the ministry of the

parish of Govan, the stipend and emoluments of a separate minister

were arranged for, and the patronage was vested in the college

authorities. [Alunimenta, i. 521, 522 ; Charters and Documents, i.

pt. ii. p. 470.]

A few years later the

Principal was similarly relieved from the necessity of regular

ministration in the kirk of the Black-friars. In 1635 the college

authorities found the upkeep of the old Blackfriars kirk too much

for their resources. It had become ruinous, and a new settlement had

to be found. An arrangement was therefore made with the Town Council

whereby that body agreed to take over the kirk, with the ground

westward from it to the meal market, and a space of eleven ells

width on each side of the kirk for enlargement of the building, if

necessary. As part of the bargain the Town Council was to pay 2000

merks towards the completion of the college buildings, the college

was to have the next best seat in the kirk after the magistrates,

and free use of the building at all times for ceremonial purposes,

and at the same time four of the "new laigh chambers" in the college

were to be assigned to the use of burgess' sons while students.

[Charters and Documents, No. cvii.] This arrangement was confirmed

by the archbishop and the Crown. Thus the old kirk of the

Blackfriars finally passed into possession of the city. [Charters, i.

pt. ii. cviii, cix.]

Another notable

windfall which accrued to the college for the completion of its

buildings was a sum of £20,000 left in 1653 by the stout old

minister of the Barony, Zachary Boyd, who was also dean of faculty,

rector, and vice-chancellor of the University. The legacy was

burdened with the stipulation that the University should publish all

its benefactor's literary works. A number of them, Zion's Flowers in

poetry and The Last Battell of the Soul in Death in prose, have seen

the light, but in merciful consideration of Boyd's memory the

authorities still delay complete fulfilment of his stipulation.

Zachary's bust, however, was piously set up by the college

authorities, and the buildings were erected at intervals. About

1690, Principal Fall records, the stone balustrade was put up on the

great stair leading to the fore common hall, "with a Lion and a

Unicorn upon the first turn." Bust, stair, and balustrade are all

still to be seen in the new college at Gilmorehill.

An excellent idea of

the student life, of the more orderly sort, at Glasgow University in

the latter half of the seventeenth century is furnished by the

extracts from the Register of Josiah Chorley published by Cosmo

Innes in his Sketches of Scotch History. A large amount of intimate

and interesting information of the same period is also to be found

in Principal Baillie's Letters and Journals. There can be no

question of the tremendous effect upon Scottish character in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries which must have been produced

not only by the learning of Glasgow University, but also by the

social influence of its collegiate life. The abandonment of that

collegiate life at a later day has ever been a subject of regret to

lovers of education as distinct from mere information, and they

regard as a happy augury the present-day movement to remedy the

defect by the establishment of student hostels and an enlarged

union. |