|

DURING the first

hundred years of its existence as a burgh, Glasgow had a favourable

opportunity for increasing in trade and commerce to the limited

extent attainable at that early period. Its overlords, the bishops,

usually held high positions in the state, and were possessed of

sufficient influence at court to secure the community against

external encroachment or undue interference, while the peaceful

condition of the country allowed the internal organisation to

develop. The inhabitants were not slow in adapting themselves to

usages and procedure which in the experience of older burghs had

been found beneficial ; but there was one important distinction in

the position of Glasgow. In royal burghs, though the sovereign is

believed to have originally appointed the magistrates, the burgesses

themselves were from an early date allowed to exercise that

privilege. In Glasgow it is probable that the bishops from the first

elected the magistrates, though, as in the earliest elections of

which any record is extant, from leets primarily selected and

presented by the burgesses, a system which was continued till the

seventeenth century. Apart from this peculiarity, and the practice

of the burgesses paying rents or burgh maul to the bishop instead of

to the sovereign, administration and procedure in Glasgow were

similar to those which prevailed in royal burghs.

One of the old burgh

laws imposed restrictions against burgesses disposing of their

heritage to the prejudice of their heirs. In the event of an owner

requiring to part with heritage he was not entitled to sell it to a

stranger till it was offered to the nearest heirs and they declined

to become purchasers. [Ancient Laws and Customs, i. p. 55.] An

illustration of the operation of this law in Glasgow occurs about

the year 1268, when a burgess named Robert de Mithyngby, "compelled

by great and extreme poverty and necessity," sold his property to

Sir Reginald de Irewyn, then archdeacon of Glasgow. This was done

with consent of the seller's daughter (his heiress) and brother, who

both in the burgh court expressly consented to the transaction; "

which land," it is also stated, "was offered to my nearest relations

and friends, in the court of Glasgow, at three head courts of the

year, and at other courts often, according to the law and custom of

the burgh." In addition to the price paid by the purchaser he was

liable in a yearly rent to the bishop and his successors, but the

amounts are not stated. Of this property, which must have been

situated in a street running east and west, as it had the land of

Peter of Tyndal on the east and that of Edgar, the vicar, on the

west, possession was given to the archdeacon in presence of the "prepositi"

and bailies and twelve burgesses. "Prepositi" at that time occupied

positions of authority in the burgh which it would be difficult to

define. Perhaps the bailies were graded and the "prepositi" might be

the first in rank; but they must not be confounded with the modern

"provost," whose office did not come into existence in Glasgow till

about the year 1453. [Sir James Marwick has fully discussed the

subject in his Introduction to Glasgow Charters, pointing out that

the term frequently occurs in royal charters, and that it had a wide

application in varying circumstances. Thus the prepositus might be a

cathedral dignitary, the second officer in a monastery under the

abbot, the head of a religious college, a judge, or an official in a

town or in an incorporation or guildry (Glasg. Chart. i. pt. i. pp.

xvi, xvii).] Among the witnesses were Sir Richard de Dundovir,

Alexander Palmer and William Gley, designated " prepositi," being

the earliest magistrates of the city whose names appear in any known

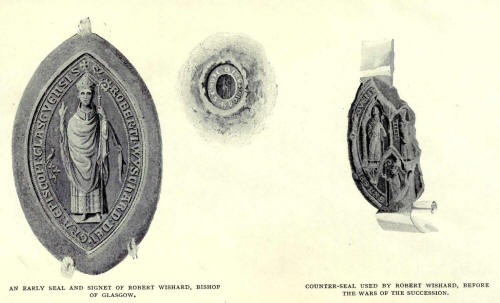

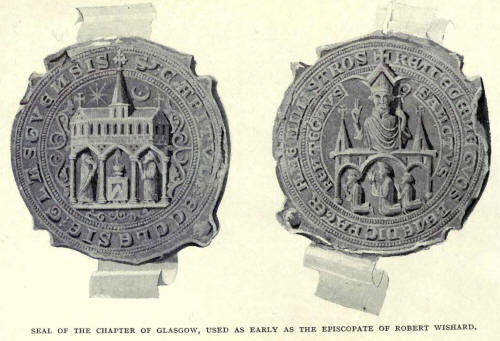

record. To the original writing the .common seal of the city was

appended, and Father Innes notes that it was " on white wax, almost

entire, and showed the head of the bishop, with mitre, namely St.

Kentigern." [Reg. Episc. No. 236; Glasg. Chart. i. pt. ii. pp.

17-19. The document from which these particulars are obtained must

have been one of those taken by Archbishop Beaton to Paris at the

time of the Reformation. In his Trans-script of Charters supplied to

the town council of Glasgow in 1739, Father Inner gives the date of

the document as "circa 1280 vel 1290," but as Archdeacon Irewyn who

acquired the property is referred to in Bishop John's charter of

11th June, 1268 (Reg. Episc. No. 218) as then deceased, the

transaction must have been completed before that date. In the copy

printed in Gibson's History of Glasgow (p. 303), which seems to have

been taken from another transcript, the date is 1268.]

In the year 1285

another burgess, constrained by poverty, sold to the Abbot and

Convent of Paisley a property described as lying in the Fishergait,

5rope pontem de Clyde, [Reg. de Passelet, p. 399• Adam of

Cardelechan was the name of the burgess, and, for authentication of

the charter granted by him in favour of the abbot and convent, there

were appended his own seal, together with the common seal of the

burgh and the seal of the official of the court of Glasgow.] thus

establishing the important fact that by that time the river was

spanned by a bridge. Fishergait corresponds with the modern

Stockwell Street, where the first stone bridge was erected. The

bridge referred to in 1285 was doubtless constructed of timber, and

may have been there from a much earlier period. The bishops had

valuable lands on the south side of the Clyde. Two hospitals were

erected there, and for ready access to these it was desirable that

something more convenient than a ford should be provided. One of the

hospitals was used for the reception of lepers. An old burgh law

required that those afflicted with leprosy should be put into the

hospital of the burgh, and for those in poverty the burgesses were

to gather money to provide sustenance and clothing; [Ancient Laws, i.

p. 28. ] and another act refers to the collection of alms "for the

sustenance of lepers in a proper place outwith the burgh." Perhaps

in Glasgow special care was bestowed on lepers, as Joceline of

Furness, writing in the twelfth century relates that St. Kentigern

cleansed lepers in the city of Glasgow, and that at his tomb,

likewise, lepers were healed.' The precise date of erection is not

known, but the hospital may have been established as early as the

twelfth century. The other hospital, that of St. John of Polmadie,

was governed by a master, keeper, or rector, was used for the

reception of poor men and women, and was in existence at least as

early as the time of King Alexander III.; but neither of this

hospital nor of that which accommodated the lepers, is there much

information procurable till a later date.

On his leaving

Glasgow Bishop `William Wischard was succeeded by his nephew, Robert

Wischard, archdeacon of Lothian, who was elected apparently in 1271

and was consecrated by the bishops of Dunblane, Aberdeen and Moray,

in the end of January, 1272-3. In the peaceful days which preceded

the War of Independence the new bishop devoted much attention to the

completion of the cathedral. Arrangements seem to have been made for

the erection of a bell-tower or steeple and a treasury, and Maurice,

lord of Luss, by a charter granted at Partick, in August, 1277, sold

to the bishop all the timber necessary for the work, giving the

artificers and workmen free access to his lands and woods for

cutting down and removing the timber, all horses, oxen and other

animals employed on the work being allowed free grazing during the

time they were on his grounds. It has been conjectured that the

steeple and treasury for the erection of which preparations were

made in 1277 were the two western towers of the cathedral, but we

have no information

as to the progress of the work, and the precise date of the erection

of the towers is uncertain. Later on the bishop obtained supplies of

trees from Ettrick Forest and other places for building in various

parts of his diocese; but it was alleged that instead of using some

of these for the woodwork of the cathedral they were employed in the

construction of instruments of war for the siege of Kirkintilloch

castle, then held by the English. [Burton's History of Scotland

(1897 edition), iii. p. 429; Book of Glasgow Cathedral, p. 182;

Bain's Calendar, ii. No. 1626; Dowden's Bishops, p. 306.]

In the early years of

Robert Wischard's episcopate much anxiety prevailed in

ecclesiastical circles with regard to the revaluation of church

benefices for the imposition of taxation. For the general purposes

of the church, for meeting the demands of Rome and her papal

legates, as well as in bearing a proportion of expenditure for

national requirements, funds had hitherto been raised on the basis

of a valuation supposed to have been in existence as early as the

reign of William the Lion, and the clergy strenuously resisted all

attempts to vary it according to the progressive value of livings.

The modes adopted in levying contributions were also sometimes

objectionable. Thus, in 1254, Pope Innocent IV. granted to Henry

III. of England a twentieth of the ecclesiastical revenues of

Scotland and in 1268 Clement IV. renewed that grant and increased it

to a tenth. The money was required for a crusade which was then

being organised; but when Henry attempted to levy it, the Scottish

clergy resisted and appealed to Rome, and it is believed that the

English king did not succeed in raising much of the tenth in

Scotland. Another demand was made in 1266, six merks being asked

from every cathedral church and four merks from every parish church,

to pay the expense of a papal legate who had been sent to England to

compose the quarrels between Henry and his barons, but both king and

clergy resisted the claim.

In the year 1275

Baiamund de Vicci was sent from Rome to collect the tenth of

ecclesiastical benefices in Scotland, for relief of the Holy Land,

and as he was collecting not through the English king but for the

Pope direct the clergy did not object so much to the imposition as

to the introduction of a new basis of assessment. They insisted for

their ancient valuation, as the approved rule of proportioning all

church levies, but notwithstanding their intreaties the Pope adhered

to his resolution of having the tenth of the benefices according to

their true value. Known in this country as " Bagimont's Roll," the

valuation of 1275 was long detested by churchmen; but as time wore

on and livings increased in value, it had its turn of favour, and in

an act of parliament passed in 1471 it was stipulated that

collections made for the see of Rome should be conform to the "use

and custome of auld taxation, as is contained in the Provincial

bulk, or the auld taxation of Bagimont."

Ancient valuations of

church benefices for many parts of Scotland have been preserved, but

neither any ancient valuation nor even that of "Bagimont" in its

original state exists for Glasgow diocese. In the printed Registrum

Episcopatus a copy of " Bagimont his Taxt Roll of Benefices," as

contained in a sixteenth century transcript, is given, but in that

shape it is regarded as evidence for nothing earlier than the reign

of James V. [Origines Parochiales, vol. i. pp. xxxiv-xxxix. ] Yet

such as it is the Roll furnishes the earliest valuations we now have

of Glasgow benefices, and an abstract may here be given. The

thirty-two prebends possessed by the canons composing the chapter of

Glasgow cathedral were of the cumulo yearly value of £4,796. The

parsonages and vicarages, so far as remaining in connection with the

diocese, but excluding several churches which had been transferred

to monasteries or other religious houses, such as Rutherglen, which

then belonged to Paisley Abbey, are

grouped in deaneries

and the cumulo amount in each deanery is as follows:—Peebles, £786;

Teviotdale, £666; Nithsdale, £1,353; Annandale, £346; Rutherglen,

£906; Lennox, £50; Lanark, £900; Kyle and Cunningham, £533; Carrick,

£260. The total valuation was about £ZZ,000, [Reg. Episc. i. pp.

lxii-lxx. Shillings and pence are omitted; and it may be mentioned

that there is a discrepancy of a few pounds between the amount of

the sums stated and their summation in the print. The bishopric,

which is not noted in Bagimont's Rcll, is valued in another list at

ii,7oo (lb. p. lxxi).] and the levy of a tenth of that amount would

accordingly form a substantial contribution from the diocese. |