|

IN the collections of

ancient statutes an attempt has been made to distinguish those

attributable to the reign of King William; and of the legislation so

marked a few chapters, specially applicable to burghs, contain

provisions substantially identical with clauses in the charters of

that period granted to various individual burghs. By one of these

laws the merchants of the realm were authorized to have a merchant

guild, with liberty to buy and sell in all places within the

liberties of burghs, so that each one should be content with his own

liberty and that none should occupy or usurp the liberty of another.

[Ancient Laws, i. p. 60.] This seems to mean that the merchants

within the trading liberties of any particular burgh were entitled

to form themselves into a fraternity, and it was in this way that

merchant guilds were constituted in actual practice. In Glasgow the

provisions of the general law were not incorporated in any burgh

charter till 1636, long before which time the merchants had been

classed together, first perhaps as an ordinary association and

latterly as a guildry with a dean at its head. [Glasg. Prot. No.

1662; Glas. Rec. i. pp. 95, 96.]

By another statute it

was ordained that no prelate or churchman, earl, baron or secular

person, should presume to buy wool, skins, hides or such like

merchandise, but goods of that sort were to be sold only to

merchants of the burgh within whose sheriffdom and liberty the

owners dwelt. To secure the due observance of this provision all

merchandise was to be offered to the merchants at the market and

market cross of the burgh, and such king's custom as was exigible

was thereupon to be paid. By a separate law, perhaps of later date

than that of William, all dwellers in the country, as well

freeholders as peasants, having marketable wares for sale, were

directed to bring such to the king's market within the sheriffdom

where they happened to dwell. Under this statute, if in operation

before 1175, the market to be frequented by dwellers in Glasgow

barony would be that of Rutherglen, and it is known that, whether

under the statute or not, officials of the burgh of Rutherglen

collected the king's custom in the barony both before and for some

time after the founding of the burgh of Glasgow. But the Glasgow

market, possessing in other respects all the privileges conferred by

statute or burghal usage, would be exclusively resorted to by the

barony traders, and though local customs would be exacted there it

is probable, from what is known of subsequent practice, that the

king's custom would be gathered elsewhere.

With regard to

foreign trade it was ordained that no merchant of another nation

should buy or sell any kind of merchandise elsewhere than within a

burgh, and such trading was to be conducted chiefly with merchants

of the burgh and ships belonging to them. Foreign merchants arriving

with ships and merchandise were not to "cut claith or sell in penny

worthis," but were to dispose of their goods wholesale to merchants

of the burgh. Such provisions can scarcely have been of much benefit

to Glasgow till a long time after the beginning of the thirteenth

century, and they are not imported into the early charters of the

burgh. But, as was shown in the negotiations which Glasgow

subsequently had with Renfrew and Dumbarton, the merchants of the

burgh were acknowledged to be entitled to the privileges conferred

not only by the general law adopted in William's reign but also by

the implied terms of the burgh's own charters. Thus in an action of

declarator by Glasgow against Dumbarton, decided by the Court of

Session in favour of Glasgow, on 8th February, 1666, it was pleaded

that, as a necessary and essential point of the freedoms conferred

by King William's charter of 1175-8, the burgh had the right and

privilege of merchandizing, sailing out and in with ships, barks,

boats and other vessels upon the Clyde, and arriving, loading and

unloading goods at places convenient within the river. [Ancient

Laws, i. pp. 60-62, 183 ; River Clyde (1909), p. i. King William's

statutes above referred to are summarised and renewed in a charter

by King David II. to his burgesses throughout Scotland, dated 28th

March, 1364 (Convention Records, i. pp. 538-41).]

Engrossed in the

Register of Glasgow Bishopric, in thirteenth century handwriting,

are a few ordinances corresponding with privileges granted by King

William to some of the royal burghs, but none of these provisions

have been embodied in the Glasgow charters, the general law being

considered of sufficient application. The enactments referred to

provide (1) That no one residing outwith a burgh should have a

brew-house, unless he had the privilege of "pit and gallows," and in

that case one brewhouse only; (2) no one residing outwith a burgh

was allowed to make cloth, dyed or cut; (3) no one travelling with

horses or cows, or the like, was to be interfered with if he

pastured his beasts outwith meadow or standing corn; and (4) no

bailie or servant of the king was to have a tavern in the burgh or

to be allowed to sell bread or bake it for sale. [Reg. Episc. No.

536; Ancient Laws, i. 97-98.]

In addition to the

forty shillings, yearly, which he had previously given from the

ferms of the burgh of Rutherglen, for the lights of the cathedral,

King William, in the time of Bishop Joceline, had from the same

source bestowed three merks yearly for the sustentation of the dean

and subdean. To this latter grant other three merks were added, in

the time of Bishop William, so that the dean and subdean might be

decently provided with surplices and black capes conform to the

statute of the church; and by a charter, granted between the years

1200 and 1202, the king charged his prepositi of Rutherglen, on

behalf of himself and of Alexander, his son, to pay the six merks

yearly to the clerics within the church of St. Kentigern. [Reg.

Episc. No. 92.] In connection with these church grants it may also

here be noted that Robert of London, son of the king, gave out of

his lands of Cadihou a stone of wax, to be delivered at Glasgow

fair, yearly, for the lights of the cathedral. [Ibid. No. 49.]

Bishop Joceline died

at his old abbey of Melrose on 17th March, 1198-9, and was buried

there, in the monks' choir. Then followed, within the short space of

eight years, the placing of no fewer than four of his successors.

Hugh de Roxburgh, chancellor of Scotland, though elected, was

probably not consecrated, as he did not survive Joceline as much as

four months. William Malvoisine, who also was chancellor and held

the office of archdeacon of St. Andrews, next succeeded. He was, by

command of the Pope, consecrated by the archbishop of Lyons, in that

city, on 24th September, 1200, but he was translated to St. Andrews

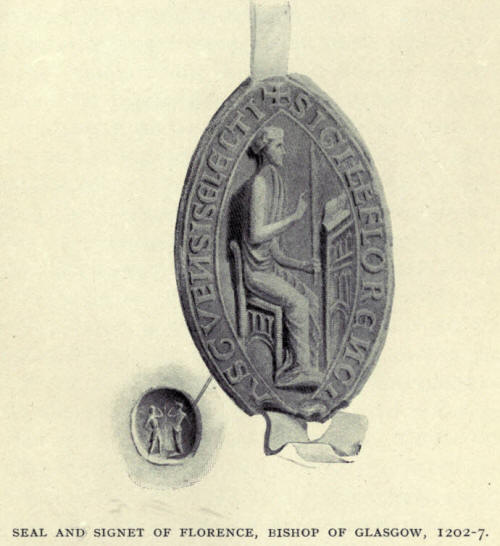

on 20th September, 1202. Florence, a nephew of King William, being

son of his sister Ada and of Florence III., count of Holland, seems

to have been elected in 1202. In the following year he was

designated bishop elect and chancellor of the king, but he was never

consecrated, and he resigned before December, 1207. The next bishop,

Walter, chaplain of the king, was elected on 9th December, 1207. He

was, by leave of the Pope, consecrated at Glasgow on 2nd November,

1208, and held the bishopric for the fairly long period of

twenty-four years. [Dowden's Bishops of Scotland, pp. 299-301]

In the latter years

of King Richard of England, with whom he always remained on terms of

friendship, William had in vain endeavoured to recover

Northumberland and Cumberland, and after John succeeded to the

English throne, in 1199, these attempts were renewed with no better

success. Another subject of contention arose in consequence of

English schemes for the erection of a fortress at the mouth of the

Tweed, all of which were frustrated by the Scots, but though, in

1209, armies had been raised on each side, the two kings were in no

warlike mood, and an amicable arrangement was adjusted through the

mediation of their barons. Troubles, however, were not wholly

extinguished in some of the outlying districts of the country. In

the extreme southwest peace had been maintained since the settlement

with Roland, lord of Galloway, in 1185, but the northern counties

were not yet pacified. In 1196-8 three successive campaigns against

rebels in the earldom of Caithness resulted in the complete

overthrow of Earl Harald and his insurgent forces; and in the year

1211 a similar result was secured in the Ross district by the defeat

of Guthred MacWilliam, a Celt who claimed the Scottish throne

through descent from Malcolm Canmore.

King William died at

Stirling in 1214 and was buried at Arbroath in the abbey which had

been founded by himself in honour of St. Thomas of Canterbury.

"Oure Kyng off

Scotland Schyr Williame

Past off this warld till his lang hame,

To the joy off Paradys,

(Hys body in Abbyrbroth lyis)

Efftyre that he had lyvyd here

King crownyd than nere fyfty yhere."

[Wyntoun, ii. p. 228. See also the remarks of a contemporary of the

king in Melrose Chronicle, p. 155,]

During the visit of

William de Malvoisin to Lyons for his consecration he seems to have

asked information for his guidance in the management of his

bishopric, and a letter he received on the subject from John de

Belmeis, a former archbishop of Lyons, has been preserved. At the

outset of his letter the ex-archbishop expresses his belief that

Bishop William will find, on his return journey, men much more wise

and prudent than he was to afford the desired information,

especially while passing through the city of Paris "where there is

no doubt you can find many who are skilled both in divine and human

law." But he proceeded to explain the plan he himself had followed,

in accordance with the example of his predecessors and the

experience of his own times. The see of Lyons, said the archbishop,

"has the very ample jurisdiction which you call `barony'," and there

was a seneschal to whom was entrusted the responsibility for legal

business, and who dealt not merely with pecuniary causes but saw to

the punishment of crimes and serious offences, in accordance with

the custom of the country. " But," adds the archbishop, "if the

nature of the offence inferred either the penalty of the gibbet, or

the cutting off of members, I took care that not a word of this was

brought to me." It was the seneschal, with his assessors, who

decided about such matters, though it was the archbishop who gave

them authority to take up and decide them, and whatever revenue was

derived from causes of that kind was carried to his account, after

deducting the perquisites of his seneschal, who was entitled to a

third of the proceeds for his trouble. On another branch of Bishop

William's inquiry, the late archbishop stated that clerics, and

especially such as had been advanced to holy orders, were strictly

prohibited from prosecuting in a secular court cases of robbery or

theft, or if they could not avoid that they were on no account to

proceed to single combat, or the ordeal of red-hot iron, or of

water, or any procedure of that sort. [The ordinance by King William

as to the "judgement of bataile or of water or of bet yrn," in this

country, is referred to antea, p. 51. Facsimiles (one third of

original height) are here given of pages of Glasgow Pontifical Book,

preserved in the British 11luseum. No. i facsimile shews, in ritual

of hot-iron ordeal, the consecration of the iron. No. 2 shews (on

foreshortened page to left) in ritual of hot-water ordeal the

adjuration of the water, and (on full page to right) direction as to

immersion of the accused man's hand. The photographs for these

facsimiles have been kindly lent by Dr. George Neilson who procured

them in illustration of his Rhind Lectures on Scottish Feudal

Traits.]

It is long after this

time before any direct information is obtainable as to the mode of

government followed in Glasgow barony, unless something may be

learned from King Alexander's confirmation of the Bishop's lands in

free forest, in 1241; but according to fifteenth century practice, a

bailie and his deputes are found exercising somewhat similar

authority to that assigned to the seneschal of Lyons and his

assessors in 1200, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that a like

system may have prevailed in Glasgow during the intervening period.

No prohibition

against duelling by churchmen, such as that enjoined abroad, seems

to have been in operation in this country till a few years after the

date of the archbishop's letter. By a Bull obtained on 23rd March,

1216, at a time when Malvoisin, then bishop of St. Andrews, was in

Rome, and directed to all the faithful of Christ throughout the

province of York and the kingdom of Scotland, Pope Innocent III.

stated that it had come to his ears that a certain baneful custom,

which should rather be called an abomination, as being utterly in

defiance of law and of the credit of the church, had from of old

established itself within the kingdom of England and of Scotland and

was still wrongfully adhered to, namely, that if a bishop, abbot, or

any cleric, happened to be challenged for any of the grounds of

offence in respect of which a duel was wont to take place among

laymen, he who was challenged, however much a cleric he might be,

was compelled personally to undergo the ordeal of duel. The Pope,

therefore, utterly detesting the custom, as offensive to God and the

sacred canons, commanded that no one thenceforward, under pain of

anathema, should presume to persist in the practice. But this papal

fulmination did not alter the law of the land, and twenty years

after its date the bishops and clergy of England are found seeking

to procure from the kings of England and Scotland exemption from

liability to wager of battle. [Reg. Episc. No. I io ; Statutes of

the Scottish Church : Scottish History Society, vol. 54, pp. 288-93;

Neilson's Trial by Combat, pp. 122-6.]

So far as statutory

law was concerned the burgesses of royal burghs seem to have had

greater protection from the call to battle than the clergy could

claim. There was nothing to prevent two burgesses of the same town

settling their quarrel by an appeal to arms, but if a rustic, or

non-resident burgess, challenged a resident burgess, the latter was

not bound to fight, and was entitled to defend himself in the burgh

court. If, however, the challenge came from the resident burgess the

outside party had to defend himself by battle, and in such a case

that had to be fought outside the burgh. [Other privileges are noted

in Edinburgh Guilds and Crafts (Scottish Burgh Records Society), pp.

12, 13.] |