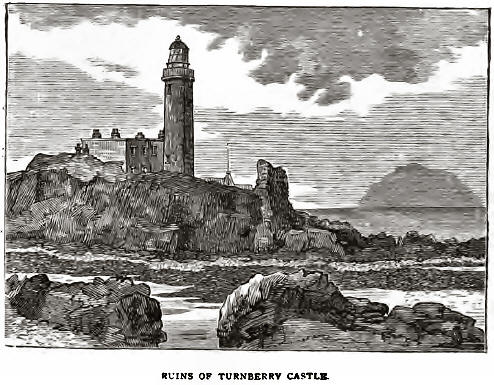

THE records of Bruce's

early life have perished, but it is almost certain that he was born at

Turnberry Castle, the home of his mother, on 21st March, 1274; and as

there were no Academies or Universities in Scotland in those days, it is

highly probable that he received at least the rudiments of his education

at Crossraguel Abbey. He owned extensive estates in Carrick, in

Annandale, and in Yorkshire, but his chief inheritance was his claim to

the Scottish crown. There was another claimant—the Red Comyn, connected

with Balliol; but Edward I. was minded to keep the crown to himself.

Under these circumstances, Bruce, it is supposed, made overtures to the

Comyn for his support, which the latter betrayed to Edward. Apprised of

his danger by a friend sending him a purse and a pair of spurs, Bruce

fled from London, and arranged for a meeting with the Comyn in the

Church of the Greyfriars, Dumfries. There the quarrel between the two

came to a head, and Bruce in a moment of passion stabbed his rival,

which was followed up by Sir Roger Kirkpatrick, with the

well-known-response—"Tse mak siccar"

Bruce was now outlawed

both by Church and State, and felt that his only chance of safety lay in

"Audacity." He therefore set out for Scone, near Perth, and there, at

the age of 32, assumed the crown. But what a poor coronation his was!

There was no historical crown or sceptre, for Edward had taken these

away; and no "Stone of Destiny" on which the Scottish monarchs used to

be enthroned, for it was also taken away; and no enthusiastic crowds of

nobles and gentry to cry "God save the King!" As Bruce's Queen remarked,

sadly enough—"They were merely playing at Royalty." And so indeed it

proved. In a few months, his forces were defeated, his Queen a prisoner,

his brothers slain, his friends scattered, and himself an exile with a

few followers on Rathlin—an island off the coast of Antrim, 6 miles long

by 1½ broad, with a population in these days of some 500 persons.

But this was the extreme

ebb in Bruce's fortune. Soon •the tide began to flow, and it never

ceased flowing till it carried him to Bannockburn and the throne of an

independent kingdom. Accepting the seven times repeated attempt of the

little spider to fasten its thread to the rafters as an omen from

heaven, Bruce in the spring of 1307 crossed over to Arran, and thence to

Carrick; and who that saw that poor fleet of fishing boats with his men

on board, rowing over in the dark from King's Cross Point on the Bay of

Lamlash to the Bay of Maidens, could have fancied that they carried our

Scottish Caesar and his fortunes ! And yet so it was. The very light

that guided him, it was afterwards believed, was a fiery pillar like

that of the Israelites of old ; and this belief was a true one.

And now began a brilliant

series of uninterrupted successes, making that period of Scottish

history a very romance. First, the garrison quartered in Turnberry

village was cut off. Then Percy, who held the Castle, abandoned it in

disgust, after burning the old Abbey of Crossraguel by way of revenge.

Then Douglas Castle, Roxburgh Castle, Dunbarton Castle, Linlithgow

Castle, Edinburgh Castle, one :after the other, fell before him, leaving

only Stirling Castle, which the governor promised to surrender by the

end of June, 1314, if it was not previously relieved.

When Bruce began this

career of success, Edward I. arose in his wrath, and vowed never to rest

till Scotland was finally subdued. He had, with his army, reached a

village within three miles of the Scottish Border, where, however, he

was awaited by a greater Warrior than himself. But before he died, he

made his son swear to carry on the war, and take his body along with

him. But Edward II. had little stomach for

fighting, and so he returned to London, and buried his father in a grand

tomb still to be seen in Westminster Abbey, where a Latin inscription

declares him. to have been "Malleus Scotorum"—the hammer of the Scots.

And so indeed he was. But the anvil in this case outlasted the hammer,

and a great many more hammers since.

At last, Edward

II. was driven, as a point of honour, to make

an effort to relieve Stirling Castle, and recover the conquests of his

father. And thus it came to pass that on Monday, 24th June, 1314, the

military strength of England found itself facing the military strength

of Scotland, on the big sloping braes of Bannockburn. The disparity in

numbers was great—100,000 against 39,000. But this was-more than

counterbalanced by the oyer-confidence of the English and the folly of

their King, as matched against the bravery of the Scots and the skill of

Bruce.

In the fight that

followed, we are called to notice several things about our Carrick hero

which speak well for him, And first, there is his piety, which not only

caused him to-throw himself fervently on God, but called on his soldiers

publicly to do the same. Then, his skill in the choice of ground; then

his personal prowess; as seen in the duel with De Bohun; then his

watchfulness, which first detected the secret march of the English

towards Stirling Castle; and finally, his wisdom in adopting the old

Hebrew custom of asking the men themselves to decide whether they should

fight or not. For Burns's words in "Scots wha hae" are true to fact; and

before the battle was joined, Bruce made intimation to his men that he

was quite willing to retreat if they so wished it. But the cry was

unanimous to remain and fight it out to the end.

The policy of Bruce, with

his smaller force, was to act on the defensive, leaving the attack to

the English. He drew up his men in hollow squares or circles, the outer

spearmen kneeling, while the bowmen shot from within. It was the

formation of Waterloo, and had all Waterloo's success. It was the first

appearance, on a great scale in our history, of "that unconquerable

British infantry" before which the chivalry of Europe was fated to go

down. And the result, as every one knows, was a great victory for the

Scots, which practically settled the question of our national

independence.

About a mile south of

Dunbarton, there is a farmhouse by the road side called Castle hill,

with a rocky knoli crowned with trees beside it. Although hardly a stone

remains on it, this was the site of the ancient Castle of Cardross,

where Bruce died, June 7th, 1329, aged 55 years. He died of a skin

disease, brought on by his early hardships. One of the pleasures of his

old age, we are told, was to take a sail in his yacht towards Turnberry,

where he was born; and one of his latest acts was to build and endow an

Hospital for lepers at King's Case Well, near Ayr. When he felt himself

dying, he called his old comrade, Sir James Douglas, to him, told him he

had been a great sinner and had shed much blood, but that he had meant

by way of atonement to go and fight in the Holy Land against the Moslem.

Would Sir James go in place of him, and carry his heart along with him?

Sir James promised to do so, although on his way he fell in Spain, in a

battle with the Moors.

King Robert's body now

lies in Dunfermline, and his heart in Melrose Abbey. But he himself is

enshrined in his people's hearts as "the good King Robert.'' He was the

people's king. They had stood by him in his days of adversity, and he

ever after stood by them. And it was this district of ours that gave him

birth, and laid the foundation of the old saying—"Carrick for a man!" He

made Scotland a kingdom instead of a province; and in many a dark

passage of our after history, such as Flodden, people sighed for the

master hand that knew how to rule and fight.

Oh for one hour of Wallace

wight,

Or well-skilled Bruce to rule the fight,

And cry "St. Andrew and our right!"

Another sight had seen that mom,

From Fate's dark book, a leaf been torn,

And Flodden had been Bannockburn!