IT was Miss Boyd of

Penkill who first drew my attention to the fact that the oldest

tombstones in this district had merely a sword to indicate a man, and a

pair of scissors to indicate a woman. And she supported this by adding

that there was such a stone to be seen in the Churchyard of Old Dailly.

I ventured to remark at the time that perhaps the drawing represented a

Cross rather than a sword: but my supposition has been shown to be

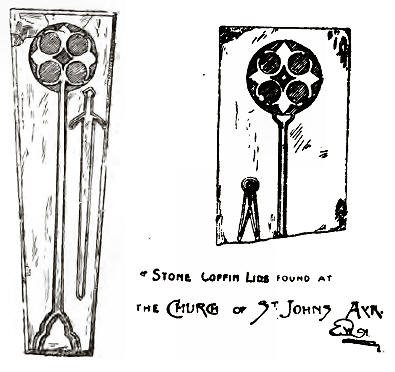

groundless by the recent discovery of several stone coffins in the

burying-ground of old St. John's Church, Ayr, on which both the cross

and the sword are carved as represented above.

Certainly, the fact of a

sword being considered the emblem of a man throws a strong side-light on

the manners and customs of an age when, as one of Miss Boyd's own

ancestors remarked, "to be without the knowledge and practice of arms

was only to be half a man." While the scissors, as emblematic of a

woman, represents an age when women were more satisfied than they are

now to preside over the private concerns of the Home Department. The

scissors here represented are somewhat primitive in appearance, and

similar to what used to be called "Weaver's shears"; while the sword is

just as devoid of grace of form. But there is this to be said, that the

scissors are at least not out of harmony with the Cross by their side;

while it is somewhat hard to reconcile the sword with the mission of

Him, one of whose main objects in dying was to bring Peace on Earth.

Taking this primitive

form of Epitaph as belonging, at the latest, to the fifteenth century,

the next most ancient form in our district brings us down to the

sixteenth century, of which we possess, at least, two specimens. The

oldest is in Kirkmichael Churchyard, and reads as follows:—

In the next century (the

seventeenth) the same forms of stone and lettering were continued, but

towards the close of it, small upright slabs were introduced with sunk

letters, instead of raised ones, and it was stones of this pattern that

"Old Mortality" hewed, and which indeed were the only ones at that time

possible among the poor. Tombstones of this pattern are common enough in

our old churchyards, and one of them in Girvan reads thus:—"In memory of

Fergus M'Alexander, minister of the Gospel at Bar, who dyed Feberuar 15,

1689. His age, 73." This man was the first Protestant minister of Barr,

was "outed" along with the other ministers of Carrick in 1662, survived

the Covenanting persecution, and was restored to his old parish again,

when the dark days were over.

In the next century (the

eighteenth) the days of florid Epitaphs began, when no bad people died,

and everybody was lauded to the skies. This was the age, too, when the

backs of tombstones were utilised for allegorical drawings of Death, the

Fall, men ploughing, ships sailing, &c. This was the time, too, when

home-made poetry was in the ascendant, when every Covenanting martyr had

his laureate, and people made it a pastime to write metrical Epitaphs on

each other. Of these I shall only quote two, both connected with

Kirkoswald, and I don't quote them for imitation, but simply as

indicative of the manners of the time.

Ah me! I gravel am and

dust,

And to the grave descend I must;

A painted piece of living clay,

Man, be not proud of thy short day.

The next was composed for

himself by a Sadducee of Kirkoswald village, whose descendants, however,

sensibly refused to have it inscribed.

The man who did this stone

erect,

To Death has paid his Kane;

If his opinion be correct,

He's ne'er to rise again,

Unless the sexton wi' his shools

Shall turn him up among the mools.

The present century is

returning to the simplicity and Christian tone which characterized the

Epitaphs of the Roman Catacombs. Verses of poetry have given place now

to simple words of Scripture, and fulsome eulogies to a bare statement

of name and date. And what more is needed ? We shall all be forgotten in

a few years, and the friends who survive us won't need to be reminded of

our virtues. I confess, however, I like to see something characteristic

even on a tombstone, and I still remember with pleasure the two lines,

chosen by himself, which concludes the epitaph of William Carey, the

first English Missionary to India, in Serampore Cemetery—

"A wretched, poor, and

helpless worm,

On Thy kind arms I fall."

And in Grange Cemetery,

Edinburgh, I was pleased to observe that Alexander Duff, the great Free

Church Missionary to India, had sunk all difference of churches in these

words on his tombstone:—"First Missionary of the Church of Scotland:'