THE parish of Barr is one

of the most extensive in Carrick, but at the same time the least

populous. There is only one village in it; the other habitations

consisting of the farmhouses scattered sparsely over its wilderness of

hills. The Stinchar is its main stream, and what arable land the parish

possesses lies chiefly along its banks. When the traveller leaves the

valley of the Stinchar, he finds himself in an unknown region of moors

and mosses, trod by no foot but that of the shepherd in charge of his

sheep, or that of the sportsman in quest of game. It may be called

indeed the Highland parish of Ayrshire, having higher hills, and more of

them, than any other.

Perhaps the most

picturesque spot in Barr is the well-known Pass into Galloway, called

the Nick of the Balloch. This begins at the farmhouse of Pin valley,

about four miles from Barr village, and ascends along the side of a hill

for nearly two miles, having neither fence nor parapet to prevent the

heedless traveller from being hurled into the ravine beneath. It is

indeed a striking road, and the view from its summit, when you have

Ayrshire on one side and Galloway on the other, is a sight worth going

some distance to see. The parish extends several miles beyond the Nick

of the Balloch into the valley of the Minnoch, from whose side rises

Shalloch-on-Minnoch to the height of 2,520 feet.

The oldest building in

the parish is the ruin popularly known as Kirkdandie. It is situated

about 1^ miles below the village on a rising ground overlooking the

Stinchar. The name is spelled in so many ways that it is difficult to

say what is its real meaning. Kirk-Dominae and Kirk-Dominick have both

been suggested, although, to make confusion worse confounded, we are

told it was dedicated to the Holy Trinity. But, apart from the name, we

know that this was the original Roman Catholic Church of the district,

until the new parish was erected (out of portions of Girvan and Dailly)

in 1653, at which date a church was erected at Barr village, which has

only recently been removed.

The walls of the old

church of Kirkdandie are still Standing, with the exception of the east

gable, near which the High Altar stood The hewn stones at the door have

been removed, and the only spot of interest remaining seems to be the

Ambry, a recess in the wall about a foot square, where the portion of

the bread not consumed at the Mass was preserved, as well as the vessels

used in the observance of that rite. The Manse and the Manse garden,

with a few fruit-trees, are still to be seen, and high up on the face of

the hill behind are the walls of a small building which formerly

enclosed a Holy Well (called the Stroll Well here), whose •clear waters

still gush out abundantly from a cleft in the rock.

But it is the commercial

associations of Kirkdandie that have given it its chief local fame. For

in the old days, when packmen were the chief retailers and Fairs the

chief markets, the annual gathering here on the last Saturday of May was

reckoned a great event in South Ayrshire. Tents for refreshments were

thickly planted on the green sward surrounding the old ruin, sometimes

to the number of 30 or 40, where haggis was to be had whose taste made

an Irishman declare that he "could drink Stinchar dry," and whisky,

whose effects were speedily seen in fights innumerable.

But the rough fighting at

Kirkdandie Fair was nothing in interest compared with the fighting that

took place (so tradition records) on the summit of a hill called

Craigan-rarie> about ij4 miles above the village. This fight lay between

a former laird of Changue and the Prince of Darkness, and began under

the following circumstances. Changue was getting short of money, and in

order to replenish his purse, sold his soul to the Devil. After a

season, the Creditor appeared and claimed the person of the debtor. But

by this time the Laird had repented him of his bargain, and refused to

go. The Great Adversary thereupon proceeded to lay hold of him; but

Changue, placing his Bible on the turf, and drawing a circle with his

sword around him, sturdily and, as it turned out, successfully defied

his opponent. If any one doubts this wonderful story, let him go to the

top of Craiganrarie and see for himself. There he will behold the

circle, only 4½ feet in diameter, and therefore perilously narrow, with

the footprints of the doughty farmer and the mark of his Bible. Of

course, in these modern days, when nobody believes in anything, it has

been asserted that the tradition only records the visit of a priest to

claim his dues. But far be such rationalistic explanations from me or

mine. We will have the original story or none at all! Besides, is not

the whole tradition but an outward embodiment of the well-known

spiritual fact—Resist the Devil, and he will flee from you ?

Other places of interest

may be found in Pederts Stone, near the Lane Toll, where that noted

Covenanter once preached; and Dinmurchie, where Viscount Stair, author

of the "Institutions of the Law of Scotland," was born in 1619, and with

whom, in after days, Peden had some friendly correspondence. But perhaps

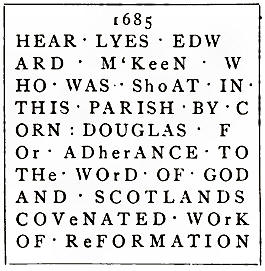

the spot most generally interesting will be found in the old churchyard,

where a small but well-preserved stone bears the following inscription

:—

It is thus Wodrow tells

the story:—"On the 28th of February, about 11 o'clock at night, Cornet

Douglas, with 24 soldiers, surrounded the farmhouse of Dalwine (still

standing about four miles above Barr village). There they apprehended

David Martin, who dwelt in the house with his mother; and finding Edward

M'Keen (the name is spelled Kyan by Wodrow), a pious young man from

Galloway, lately come thence to buy corn, who had fled in betwixt the

gable of one house and the side wall of another, they dragged him out,

and took him through a yard. He was asked where he lived, and he told

them, upon the water of Minnoch. When one of the soldiers had him by the

arm dragging him away, without any warning, farther questions, or

permitting him to pray, Cornet Douglas shot him through the head, and

presently discharged his other pistol and shot him again in the head;

and one of the soldiers of the party, coming up, pretended he saw some

motion in him still, and shot him a third time. He was but a youth, and

could not have been at Bothwell or any of the risings, and they had

indeed nothing to charge him with but his hiding himself. When they had

thus dispatched this man, the soldiers brought out their other prisoner,

David Martin, to the same place, and after they had turned off his coat,

they set him upon his knees beside the mangled body. One of the soldiers

dealt with the Cornet to spare him till to-morrow, alleging they might

get discoveries from him, and stepped in betwixt him and six soldiers

who were presenting their pieces. The Cornet was prevailed with to spare

him, and bring him into the house. But the fright and terror so unhinged

his reason, that he became an imbecile to the day of his death." Such

were the doings that were common in "the killing time." And the only

grim satisfaction we have is in learning that this ruffian officer, who

had previously shot John Semple at Dailly, was himself cut down, four

years afterwards, on the field of Killiecrankie.

The drawing represents

the Village of Barr, with the rushing Gregg in front and the Kelton Hill

behind. The house to the extreme right is the very neat Public School,

while those in the foreground extend towards what is called "The

Clachanfit." There are two churches, both recently erected, and these,

with the old churchyard, form the sights of a village which for neatness

and picturesqueness of situation takes a foremost place among the

charming villages of Carrick.