|

A VERY frequent utterance of

both speech and pen has it that the most attractive scenery in Britain is to

be found among the foothills of moors and mountains. In Scotland, as already

noticed, the charms of this neutral zone- between the wild and the tame are

often obliterated by the zeal of the northern farmer, and the plough at

times brushes the very edge of the heather. But the East Lothian wall of the

Lammermoors, where we closed the last chapter, is too steep and broken and

rent by ravines to suffer greatly in this way at the hands of the most

soaring agriculturist. On the Berwickshire side, it was noticed how the

moors are apt to dip to the Merse in long sombre sweeps of reclaimed moss

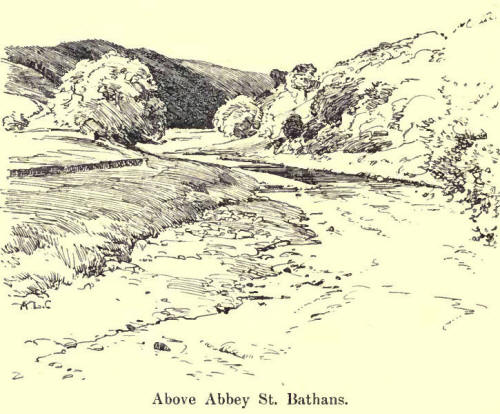

and straggling fir woods. But from Longformacus to Ellemford and Abbey St.

Bathansat the back of Duns in short -- the Lammermoors break into the low

country amid a delightful confusion of valley, woodland, and heath-clad

heights, a very labyrinth of bosky glens so intricate that in spite of one

or two tortuous narrow roads which crawl laboriously into it around the

obstructing mass of Cockburn Law, a more secluded bit of Arcady would be

hard to find. The Whiteadder, which here breaks through with resounding

voice in many miles of twisting tempestuous course, and not seldom in deep

rocky gorges not lightly to be seriously bridged for a scant traffic by

prudent county authorities, contributes to this seclusion as much as to its

scenic glories.

Abbey St. Bathans, locked

deep within it, is the heart of the region, and in the whole orbit of the

Lammermoors there is no more delightful retreat. The Whiteadder has run down

its four-mile course from Ellemford in a succession of pools and streams,

and, after a sharp bend, spreads out in a broad, straight reach, where its

waters, chastened in spirit by a low weir at the foot, roll in even current

between the lawns and groves of the laird's house on one side, and on the

other by mossy knowes clad with fern and indigenous oak woods. Hard by the

bank nestles the ancient little church which serves a parish ranging far

over hills an I moors to the edge of East Lothian. A cluster of cottages, a

manse, and some farm buildings make up the hamlet, while across the river,

where a lusty burn comes pouring down a turf-carpeted oak-shaded glen,

stands the schoolhouse and the post office. From this brief inadequate

description it may be gathered that Abbey St. Bathans satisfies every claim

to the idyllic. Moreover, it presents precisely the same appearance, if

memory serves me, save for some ornamental planting, and has practically

altered nothing since I knew it forty years ago, and used to cross the foot

bridge, still swung high over the river, on the way from Grant's House to

Ellemford. Yet this is only four miles from a great main line, and the roar

of the Edinburgh and London trains can be heard in still weather from the

hilltop above. But when the Whiteadder is high and the ford unnegotiable,

which it may be for days together, wheel traffic is entirely cut off from

the four miles of perpendicular by-way that leads to Grant's House station.

Some habitations are perennially isolated from even that steep outlet by the

picturesque arrangements of nature in which their lines are cast. `'ever

before have I seen `ilIagers in quite fine clothes trundling a wheel-barrow

with a trunk upon it a mile uphill over a moor to meet a trap as the most

expeditious method of getting to a comparatively near station, and that one,

too, on a great main line. For this is not the Hebrides! Yet I have here

watched, nay walked beside, this archaic "outfit," as the Americans would

say, more than once in a fortnight's sojourn as it proceeded laboriously up

the long, gently-sloping moor from the village to the wind-swept cross-roads

where I was domiciled.

It may be said at once that

in the whole length and breadth of the Lammermoors, from the Soutra Pass to

Grant's House, there are next to no facilities for the entertainment of the

stranger, even of the most primitive kind — a condition of things which, as

we have seen, did not obtain in former days. If he wants to explore them he

must clamber through their outer barriers with every fresh returning morn,

for with the exception, perhaps, of the pass into Ellemford, wheels of any

kind will be found more toil than profit. I was fortunate, however, in

finding a solitary exception. Now right on the very top of what in my youth

was a heathery moor, but is now partially encroached upon by pastures and

barley fields, there stood a half-ruinous house. It was the remnant, I

believe, of a small wayside coaching inn. For on a road from Duns to

Cockburnspath still existing, but in parts grass-grown, a coach is credibly

reported to have once upon a time travelled, continuing thence, no doubt, to

Edinburgh. In a portion of this tumble-down haunt of former revelry, a

strange solitary being, much given to liberty and whisky and the illegal

pursuit of game, had rigged up sufficient protection against the weather,

and sat, no doubt, free of rent. I regret very much that I had not the

pleasure of his personal acquaintance, but he had the reputation of being a

sort of chartered libertine in the rural sense of the word. Ile was

indispensable to anglers for one thing, above all in assuring a good basket

to those whose own skill was not equal to the achievement. He must also have

been useful, or was possibly so formidable to the game owners that they

winked at his notorious practice of potting grouse, partridges, or hares

—with discreet limitations no doubt —out of his drawing-room window,

together with other free - and,- easy practices. Shooting was not

arithmetically so solemn a business as it is everywhere now; and if I have

said that time has stood still on the Lammermoors, this statement must be

modified in so far that the heather in those days all over the hills grew

for the most part rankly at its own sweet will, whereas it is now

systematically burned, as everywhere else. And it must be admitted that the

young plant in bloom has a more gorgeous effect on a hillside than where it

is older and ranker. The lines of butts, too, are novelties, and undeniably

disfiguring ones, since that time, when driving was scarcely anywhere

practised. But of the poacher who provoked the insertion of this saving

clause, his weird lair had long disappeared, and in its place a small

shooting-box, in type if not literally such, had arisen amid a pleasant

little garden, and a screen of quick-growing poplars were already rustling

high all round it. A veritable little oasis was this acre of fruit and

vegetables, and flowers, amid the wide waste of sweeping sheep pastures, and

purple grouse moors, for the bloom of the heather still lingered, though

August was fast drawing into September.

It had fallen to other

occupancy, which is of no import here except for the fact that it provided

us with snug and comfortable quarters, and, of its kind, as ideal a perch

for any one who loves the moors and all that in them lies as I ever

encountered. For from the wicket-gate of the little walled garden the

Lammermoors rolled away to the westward for miles interminable, while in the

foreground we looked right down over Abbey St. Bathans and the

deep-channelled, woody

vale of the Whiteaddcr. The

intermittent call of grouse could be heard all day, and at evening they

would come flying past the windows for a brief turn on the grass pastures;

while partridges, which flourish greatly on the tillage fringes of the moor,

were calling from all sides on the seeds or barley stubbles. At the back of

us two great farms heaved up and down in big ridges to Grant's House and the

railroad three miles away. But it might have been forty for any suggestion

of a murmur from the outer world that ever reached us. I take it there was

no higher ground between us and the Ural :,)fountains to the eastward, and,

indeed, the air of the eastern Lammermoors is absolutely the most

invigorating I know of anywhere. It ought to be. A person knowledgeable in

such things would at once pick them out upon the map as geographically

calculated to enjoy the highest distinction in this particular. They are

also unenviably distinguished for perhaps the severest snowstorms that

strike the British islands. When the Storm-God is on the rampage in the

winter season, the newspaper reader with his toes on the fender probably

does not notice that almost invariably the Lammermoors and their sheep

farmers are quoted in the weather reports as among the most heavily

punished, or, at any rate, the most deeply buried in the whole country.

We started in our moorland

quarters with a thirty hours' rain —not ordinary rain, but unrelenting,

lashing torrents, borne upon a south-west gale. Now rain in Kent, or Essex,

or Warwickshire, and the like, is merely a necessary evil. It has scarcely

any aesthetic compensations at all—just a veil drawn down upon everything

out of doors that is good to look upon. Such are pre-eminently fair-weather

countries, and afford, in short, little scope for the great qualities of the

Tempest. Now, on the Wiltshire Downs a wild wet day begins to be uplifting;

on the moors it reaches the sublime. At least, it has always thus seemed to

me. To some temperaments, I know, all this is horrible. The very qualities

that brace the fancy and touch the imagination in one case depress some

other equally susceptible soul to the very depths of despondency. My

companion suffered greatly in spirits from the shrieking of the wind as it

buffeted our snug, aerial fortress of good stone and slate, and lashed the

little belt of tossing trees that fringed us out from the moors, and hurled

the rain in spasmodic douches upon the window panes for a whole night and a

day. To one of us, all this, with the chasing of the low clouds across the

endless sweeps of lonely moor, the whirling of the restless storm-harried

birds, gulls, crows, plovers, and such like, that have no shelter for their

heads, was a mild inferno. To the other, this elemental frenzy let loose in

an appropriate and responsive playground was a delight.

There were other points of

view in the establishment, of course. Our host, for instance, a genial

little man, great at a crack, whose spare hours were mainly spent by the

riverside, took a thoroughly cheerful view of the storm, though it was

blowing his apples about sadly. "Aye, but the burns 'ull fush gran' the

morrow's morn, an' I've a fine lot o' worms tae." And so they did. The

womenfolk obviously took the same view of the storm as my depressed

companion, though upon purely practical grounds natural to housewives. We

were all at one, however, in enjoying the mild excitement as to whether the

postman would cross the ford of the river Eye, whose infant streams ran down

through moorish and boggy pastures on the station side of the house. But if

a stormy day upon the moor has its sombre and weird sort of fascination for

some of us, when the clouds roll away and the sun bursts upon the battered

spongy waste, there can be no two opinions. Divergent temperaments which a

display of elemental forces thrust for the moment so mysteriously far apart

forget their difference when the curtain of morning rises on another scene;

a scene radiant with sunshine, canopied with blue skies, and balmy with soft

scent-laden zephyrs. Such, indeed, are days worth living for upon the moors,

and this was one of them. The waning heather had gathered a new lease of

life, and glowed with reinvigorated glory. The sheep pastures glistened with

a fresh touch of verdure. The brown burns shone brimming and lusty in the

valleys, and from every side came that delicious sound of gurgling waters.

Our host was away after breakfast, with "a piece " in his pocket and a bag

of worms dependent from his waistcoat button, and didn't come home till long

after dark. His family were just beginning to get anxious about him when he

turned up, still full of enthusiasm, and a basket of trout into the bargain.

As we went down the long

glistening slope towards the Whiteadder in the morning sunshine, its angry

voice away in the woods below was plain enough, keeping up, as it were, the

orgy of the preceding day, when everything else in the earth below and the

heavens above had shaken off their delirium and relapsed into a sunny dream.

It had already sunk many feet, but was still over its banks and rolling

finely down the comparatively unobstructed reach which divides the scattered

dwellings of St. Bathans. Just below the hamlet, however, the encompassing

hills begin gradually to close upon one another, their sides breast-high

with dense mantling bracken, shaggy with scattered growths of birch and oak,

ash and alder, and their feet rudely shod with huge crags and boulders. It

is just here that the river, having by this time gathered the waters of its

many tributary burns into its bosom, begins its long struggle out of the

Lammermoors into the Merse. Pent in at places by precipitous walls of rock,

from whose mossy crests gnarled and twisted trunks shake out their canopy of

varied foliage, birch and rowan, oak and alder, above the dark waters, the

whole volume of the river rushes in deep narrow fumes that in normal times

you might almost compass in a leap. Then comes a breathing space in some

wide heaving pool, where from one shore a silvery beach shelves gently away

into unknown depths, and upon the other, far out of reach of the angler's

tormenting fly, the trout. rise peacefully beneath the pendent boughs of

great forest trees.

The rush of the water in a

flood through these gorges is a sight well worth encountering many

difficulties to enjoy. And when the river has run down again, when its first

yellowy-brown fury has modified, and the succeeding "black water" stage dear

to the local worm-fisher has run gradually down through subtle shades to the

clear amber which is its normal colouring, the infinite beauty of these few

sequestered miles of river scenery can be of all times the best appreciated.

More than one warm sunny day we wiled away in delightful lazy fashion upon

the banks of one or other of these glorious sylvan pools. A lunch-basket, a

book, and a rod, not carried with serious or agitating intent, made a

complete equipment. Our resting-place was a clean grassy bank fenced about

with bracken, whence a white gravelly shore shelved into a broad heaving

pool radiant with many hues from its varying depth and its varied bottom and

flecked by the swaying shadows of oak and willow, flung over it from a woody

cliff beyond. A rush of white water above, and a long white vista of

glancing water below, vanishing into more woods and crags, beneath the

purple shoulder of a mighty upstanding hill—what better haven could there be

on a summer day? The resident population of the pool edges, too, begin in

time to tolerate the intruder. The white-breasted dipper ceases to duck and

bow at you from his mossy rock in mid-stream, and settles comfortably down,

and even ventures a ' time or two. The belated sandpiper ceases to scud on

frightened wings, but halts anon upon the silvery strand, where the perky

yellow wagtails have long been friendly. A kingfisher flashes by, a streak

of glory, and a heron beats his slow way over the trees where the cushats

stir and rustle. Not that I allowed the river to run down out of fishing

order after such a glorious spate, without anymore serious onslaught upon

the trout than intermittent contests with rising fish in one or other of

these pools of enchantment. Furthermore, I felt it a sort of pious

duty,—almost a tribute to the memory of departed youth and its friends,—to

fish once at least over the old familiar reaches between Abbey and Ellemford.

I was anxious, moreover, to see if the Whiteadder, after four more decades

of attention from a nation of fishermen, could really be the prolific

White-adder of old. It may interest the angler upon this account, if it

bores the layman, to know that about sunset the day's spoil of a companion

and myself just filled one large creel, with which we made glad the hearts

of several riverside cottagers, while the third of our angling trio had

enough in his basket to supply our house on the moor. Like every one else

here, we used the same old patterns, the spider hackles, that Stewart

popularised and swore by half a century ago, and ours were dressed by my

companion with a sapient touch as to shade and size that a sustained

acquaintance with the Whiteadder had taught him. I might add that we

returned to the water far more fish of the smaller variety than we kept. And

these rivers, be it remembered, have to stand the onslaught of skilful bait

fishermen (too much worm is the Scotsman's failing), who basket almost

everything relentlessly. I commend this little extract from a veracious

angler's diary to the reflection of some owners of mountain rivers--not to

the dog-in-the-manger sort of man, he is hopeless—hut to the generous and

well-intentioned, who is more than apt to be unduly timid about

over-fishing.

Far above these fretting

channels, upreared on a sharp shoulder of Cockburn Law, stands the Broch or

supposed Pictish camp of Edinshall. It is well calculated to astonish a

visitor unprepared for the spectacle and only familiar with the usual

prehistoric encampment concealed under centuries of turf. It certainly

astonished me, for scarcely any of my acquaintances in the Border country

seemed to know much about it, and, indeed, I had almost begun to consider

before achieving the summit whether the result would duly reward a rather

perpendicular scramble of three or four hundred feet, much of it through

dense bracken shoulder-high, though this, by the way, is not the right

approach. I breathed a note of thankfulness, however, when the top was

reached, that a worthier instinct had prevailed. For I had certainly never

seen the like before, which is not altogether surprising, as there is, I

believe, no counterpart in the whole of England and `ales, and only three or

four in Southern Scotland, of which this one is the finest specimen. Instead

of the usual grassy ditches and ramparts of an ordinary British camp, I

beheld a circular building of beautifully laid dry stone, about six feet

high and about seventy-five in diameter. It suggested the commencement of an

enormous stone tower, suddenly interrupted in the construction, and of any

period—a recent one for choice, one might conceivably imagine, so perfect

and undisturbed and even moss-free is the work. The foundation is of large

flat stones projecting beyond the face, while the filling of the interstices

by small stones is very neatly done. The walls, of whinstone from the same

hill, are about fifteen feet thick. You may walk about with ease on their

flat surface into which two or three neatly constructed chambers are built,

while the only entrance is at the east side. But this mysterious building is

merely the centre—the citadel of refuge perhaps—of a large camp and the

house of the chief. For scattered round about are quite a large number of

circular or oval stone huts of various sizes, all of them cast down, but the

broken walls remaining to the height in many cases of a foot or two. These

of course, are familiar enough, south of Tweed, as the Cytiav Gwaeddelod of

the Welsh, and numerous, I believe, in Cornwall. Around the camp, on the

three accessible sides are two deep ditches and two high ramparts. On the

northeast side, the brink of the projecting ledge, there is but a single

ditch between two low ramparts, while the steep face of the declivity has

been obviously scarped in places. It is a noble and commanding site, looking

away over to the outer hills of the Lammermoors upon their south-eastern

fringe, while far below the White-adder flashes amid crags and woods. The

name is derived from Edwin, King of Northumbria, to which province all this

country at that time appertained. But it can surely have been only as an

occupant that a Saxon was concerned with such a fortress as this? Papers

have been read and printed upon it, but, so far as I am aware, no first-rate

authorities have taken in hand or made pronouncement upon this remarkable

place.

The country people have their

legend, which, though interesting as folklore, hardly assists in the

solution of the problem. According to them, it was the lair of an altogether

troublesome giant, whose reputed achievements in the way of raiding and

rieving cast those of the Kerrs and Armstrongs, the Charltons and Robsons of

the Middle Marches into the shade. He appears to have made life intolerable

in the neighbourhood for all his days, and giants lived long. On one

occasion he was carrying away a bull on his back and a sheep under each arm

from Blackerstone, near Duns, and as he crossed the Whiteadder at the

"Strait loup" a pebble washed into his shoe, which so worried him as he

breasted the hill, that he plucked it out and tossed it down into the river,

where it still stands, weighing about two tons. I am afraid the education of

the hundred and fifty souls who inhabit the parish of Abbey St. Bathans has

been too much for the faith in such beautiful stories, though it is happily

preserved in their memory. Eighty years ago, I find by the reports of the

then minister of the parish that the schoolmaster taught not only Latin but

Greek, and charged seven shillings a quarter for this extra. No giant could

live against this. I should judge, however, from my passing intercourse both

to-day and yesterday with these dwellers in Arcady, that the old-time

flavour of classical learning, which touched this like other Scottish

parishes, had passed out of mind, and that utility holds the field. If Greek

is threatened at Oxford and Cambridge, it could hardly be expected to

maintain itself on the Lammermoors.

St. Bathans, colloquially

known as "Abbey," as will doubtless be surmised, derives its name from a

Celtic saint. There were several of the name, who appear to be distinguished

by a slight difference in the spelling of their respective navies, almost as

though they had been Edinburgh worthies and contemporaries of Sir Walter

Scott. When seventeenth-century scholars were in the habit of spelling their

own names in two or three different ways on the same page, I don't profess

to understand how these various St. Bathans of the early Celtic Church have

been disentangled from one another by their signatures, if they had any. But

no doubt there are further and sufficient reasons for identifying this

particular St. Bathan with a cousin and disciple of St. Columba and his

successor as Abbot of Iona. The missionary achievements of the great Irish

Saint in Scotland about A.D. 560 extended from the west coast all across the

country into the kingdom of Northumberland. Among the many disciples who

followed him in his wanderings was this young cousin, whom he had himself

taken charge of and reared from a boy. St. Bathan showed himself worthy of

his rearing, and performed many miracles by land and sea, and founded many

churches in what we now call Scotland, of which this was one. Merely as

evidence of their extraordinary enterprise when mischief was afoot, it may

be mentioned that it was burned by the Danes when they destroyed Coldingham.

It is much more interesting to remember that a convent of Cistercian nuns,

under the title of a priory, was founded here in the end of the twelfth

century by Ada, daughter of William the Lion, and wife of Patrick, Earl of

Dunbar. Liberal gifts of land, both by the founders and succeeding

benefactors, were deeded to the priory, and the list of them if now resumed

would show an immense rent-roll. As usual, at the Reformation they were

"alienated," in this case by the priors, and, as one would expect, the Earl

of Home had the disposal of them, and naturally gave them to a near

relation. It is in keeping with the spirit of the wholesale robbery which

distinguished this upheaval in both kingdoms, that Elizabeth Home, who thus

annexed the profits of the Abbey, assumed the title of prioress, and even

her husband, apparently without any jocular intent—perhaps because he was

the son of a bishop—took on the name of prior. Thus sanctified they

proceeded to retail the property in lots to various people, or in other

words, no doubt, to the highest bidders.

The last stones of the priory

buildings, which adjoined the church on the river bank, were carried away

more than a hundred years ago, and no doubt many walls and barns and

cottages in the hamlet indirectly owe much of their substance to the piety

of William the Lion's daughter. Part of the walls in the little church are,

I believe, remains of the original building, while the site of a chapel is

pointed out a few hundred yards to the east of the church in an enclosure,

which is still called "the chapel field." Near by, too, is St. Bathans

spring, held of old as a sacred well with all the suitable healing

properties attached to the character. The assertion that the religious

orders showed an extraordinary partiality for the most beautiful and

romantic spots is a sufficiently trite one, though undoubtedly a combination

of the necessary water and the desirable seclusion all made for this

delectable result. I know many infinitely grander and more conspicuously

beautiful monastic sites than this one of St. Bathans. But for its quite

exceptional atmosphere of peace and unchanged, undisturbed seclusion from

the world; for its situation on the verdant edge of a broad, untainted,

sonorous stream, instinct with the life and freshness of the moors; for the

grouping of the gnarled oak woods, clinging to the mossy, ferny knowes in

the foreground; for the many little wild and woody burns that come pouring

in here from far moorland sources; and lastly, for the happy decorative

touch contributed by the pleasant gardens of the laird, neither too

elaborate nor overwhelming for the picture;—in short, for its harmony in

every feature, one does not readily forget this haunt of ancient peace,

however widely one has wandered. For myself, I had carried it about through

life, but always with a more than half=suspicion that the natural

limitations, together with the fond associations of youth, all made for the

usual measure of disenchantment. But there was nothing of the kind here. I

felt, on the contrary, an almost impersonal respect for the perceptions of

callow immaturity, and an inclination to apologise for the unjust but

natural suspicions I had harboured of an unsophisticated self.

Just above the village the

large burn of the Dlonynut pours its waters into a broad, tumbling pool at

the bend of the river. A mile or so up its twisting glen, which gradually

sheds the woodland that decorates its lower reaches, once stood the church

of Strafontane, attached successively to the Abbeys of Alnwick and Dryburgh.

Originally a hospital, founded in the reign of David II., church services,

though not burials, seem to have ceased there at the Reformation, when its

parish was merged in that of St. Bathans. Within the memory of old people,

known to inc in former days, its ruins and some crumbling gravestones still

survived, but have been long since swept out of existence by the plough. Of

legendary giants, Abbey St. Bathans, as we have seen, boasts a most

efficient one. At Godseroft, a farm above the Monynut, there dwelt in the

seventeenth century something of a literary giant in his way, and the father

of a family who maintained the tradition. This was David Hume—not, of

course, the other and better-known David Hume of the Merse, but a person of

note all the same in the Scotland of his day, chiefly for his Latin poems.

He was a son of the house of Wedderburn, and furthermore wrote many tracts

on the Union of England and Scotland, though he died years before the

consummation of that long-impending political marriage, so emphatically one

of convenience, if not of necessity, rather than of love.

But I have said nothing yet

of the fine woods of larch, fir, ash, and other trees of a century's growth

that adorn the hollows and gentler slopes of the left bank of the river

below Abbey. Dating from an old quaintly-fashioned sporting seat of the

Earls of Haddington, now a farmhouse on the river bank, these groves of

large trees are grouped irregularly for two or three miles along the lower

hill slopes, and upon grassy hollows carpeted with ferns and flowers, and

abounding, like all this country, with wild raspberries of delicious4

flavour, tons of which must rot ungathered and unseen in these secluded

haunts. Since the great storm of a fortnight earlier, we had revelled in

almost continuous sunshine. But the morning upon which we bade a reluctant

farewell to the house on the moor, the heavens were descending in a steady

torrent without any of the inspiring accessories of their former outbreak.

It was barely four miles to the station, but miles of the sort that in a

storm a heavily-laden horse has practically to walk nearly every yard.

Again, too, our thoughts were turned to the ford of the river Eye, not this

time for the trifle of a postman and his light mail bag, but for ourselves.

The little Eye, however, which courses through a boggy valley between the

big farms of Quixwood and Butterdean, whose large steadings in their snug

firwood shelters are the only dwellings on the route, had considerately

deferred its serious rage. But there is no more untoward preliminary to a

railway journey than to sit in an open trap, even for three-quarters of an

hour, with buckets of water being emptied on you the whole way.

The philosopher will always

console himself for such minor mischances by reflecting how much worse they

might have been. I recalled for my own comfort a lamentable scene, witnessed

upon this very same day of the month just a year before. For upon the

platform at Haverfordwest, I had witnessed the open brake which runs daily

over the seventeen miles and the sixteen hills from the remote cathedral

town of St. David's disgorge a dozen or more passengers, drenched to the

very skin by just such a downpour as this. These wretched beings, many of

them ladies, had not a trifling railway journey like ourselves on this

occasion, but one of eight or ten hours, being all bound for London. Heaven

knows how they fared! Butterdean, now Mr. Arthur Balfour's property, perched

high on the ridge overlooking the main-line, was the last seat held by the

extinct and forgotten race of Ellem alluded to at Ellemford. There is

nothing feudal left in the comfortable and typical Berwickshire farmhouse,

approached by a carriage-drive through a grove of firs as black as night.

Probably the Ellems, who vanished from here and from ken in the sixteenth

century, lived at Kilspendie Castle, the site of which, but nothing more,

lies a few hundred yards away.

The North British railroad,

to which belongs the Berwick to Edinburgh section of this international

artery, is not prodigal of slow trains. It is all very fine to live on a

famous main-line, but there is no particular privilege in watching express

trains bounding along from London to Edinburgh, and from Edinburgh to

London, or in admiring the earth-shaking speed at . which they travel, and

the prodigious distances they run without stopping. They do not stop for

you, and, indeed, the opportunities for local pilgrimage upon this classic

highway are extremely limited, and alit, in the matter of going and

returning, to provoke ill-humour with the Powers.

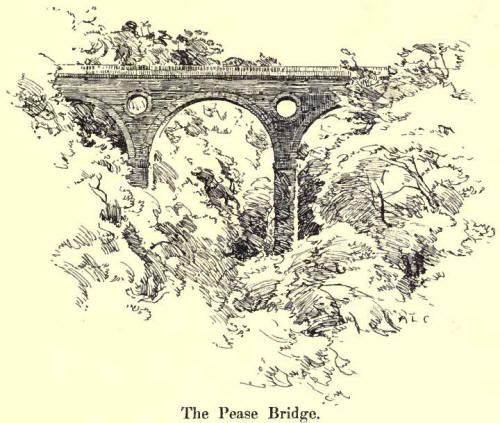

The great North road,

however, which from near Grant's House and long before it, follows the

main-line westward, pursues a singularly picturesque course through the

Pease Pass. The Pease Burn, which comes down hereabouts from the Lammermoors

and waters the narrow glen, is the best of company, though often invisible,

as it urges its clear streams through mazes of wild undergrowth, birch and

willow, spruce, hazel, and larch, and through tangled masses of heather,

broom, gorse, and wild flowers. Plunging in cascades from pool to pool, it

eventually disappears into that tremendous gorge where, deep buried between

two almost precipitous walls of unbroken foliage, it escapes through an open

and grassy vale to the sea near Cockburnspath. Standing upon the bridge

swung across Pease Dean, some 130 feet above the bed of the burn, the mass

of opulent and varied foliage that clothes the steeps upon either side, both

above and below, forms one of the most striking displays of hanging woodland

I know of anywhere.

This "Pass of Peaths," as

previously noted, has been for all time and by time's changing methods of

progress the principal route from the south into Scotland, or, to be

literal, to Edinburgh, the Lothians, and Fife, and all that country which

till modern times stood for so much of what the name of Scotland indicated.

To speculate on the mighty men of old who have traversed this narrow glen

would be much like charging one's imagination with all the illuminati who

have gone to Edinburgh in the last seventy years by the Great Northern

railroad. The men of old, however, really knew it, and with an intimacy, no

doubt, in which regard for the scenery had small part. Not one in a thousand

of the moderns have the faintest idea what they are passing through, and the

great gorge itself is invisible from the railway.

Somerset, whose ravaging

progress has from a literary point of view its lighter side in the

entertaining gossip of his special correspondent, Dr. Patten, had some

anxious hours in forcing the pass, which was held by Sir George Douglas, who

made its natural defences more formidable by digging lateral trenches at the

East Lothian end.

Alluding to the Pease Dean

itself, we are told "so steepe be these banks on eyther syde, and so depe to

the bottom, that who goeth straight downe shall be in daunger of tumbling

and the coznmer-up so sure of puffyng and Payne; for remedy whereof the

travellers that way have used to pass it by paths and footways leading

slopwise; of the number of which paths they call it somewhat nicely ye

Peaths." The Scottish trenches were found "rather hindering than utterly

letting." The limitations of modern prose, it must be confessed, seem at

times inadequate, compared to the delightful freedom of these quaint Tudor

chroniclers. "The puffying and Payne of the eommer-up " is admirable, so is

"the rather hindering than utterly letting" of an obstacle. When "his Lord's

Grace," however, "vowed that he would put it in prose, for he wolde not step

one foote out of his course appointed," the idiom takes on an obscurer form.

The Pease Pass bothered

Cromwell no little. "It is easier for ten men to defend this pass," he

wrote, "than for forty to make way." It was naturally infested by banditti,

and all kinds of stories are told of mediaeval raids made on these people,

and the huge bags of brigands' heads that were sometimes the result. Much of

it is even still mossy and boggy. No doubt in old days it was something of a

jungle. The name broadly signifies the "Pass of paths," which suggests

tortuous tracks leading through thickety swamps. For the Lammermoors rise

precipitously on one side, and on the other are the Coldingham moors. The

sites of fragments of castles are scattered all along it as far as the Merse.

As you approach Cockburnspath, once Coldbranspath, and now colloquially "Co'path,"

the considerable remains of a fortified tower stand by the roadside. The

enterprising picture post-card vendor, as previously noted, has labelled

this with indiscriminating audacity " Ravenswood." But enough of this

subject, unless to remark that the social ambitions of the Lord Keeper and

his haughty dame in the expansive period of William and Mary scarcely

harmonise with a lodging in a cramped Border tower. It assuredly remains,

however, to be set down that the MS. of the Bride of Lammermoor is at

Dunglass House, close by, the seat for some generations of the Hall family.

It is reported of a practical, but unhistorical lady tourist from Glasgow

that she misdoubted the identity of the aforesaid "Ravenswood House," as she

was convinced a family of such distinction would never have built their

house "so close to the road," alluding to the modern highway. Dunglass is a

later residence, built on the site of a really important castle. It belonged

to the Homes, when Sir George Douglas held it in 1547 against Somerset, or

rather surrendered it, for according to Patten the garrison only consisted

of "Twenty-one sober soldiers, all so apparelled and appointed that I never

saw such a bunch of beggars come out of one house in my life. Yet sure it

would have rued any good housewife's heart to have beholden the great

unmerciful murder that our men made of the brood of geese, and good laying

hens that were slain there that day, which the wives of the town had penned

up in holes in the stables and cellars of the castle ere we came." Somerset

razed the castle, but the Homes erected a larger one, and twice entertained

James I. on his journeyings south with all his retinue. In the Covenanters'

resistance to Charles I. in 1640, Lord Haddington occupied Dunglass, but was

blown up with most of his friends by the explosion of the powder magazine,

ignited, it is said, by an English page boy, in revenge for some slighting

remarks made by the earl on his countrymen.

One striking feature,

however, of this famous pass is the manner in which it opens out into the

rich and fertile fields of East Lothian. And further, how just at the

entrance, the way out is obstructed by two parallel and deep-wooded deans,

threaded by the streams which, running down from the Lammermoors, have in

the course of ages cut through the red sandstone. Modern traffic makes

nothing of such obstacles. But in old times one seems to see them as two

great trenches cut by nature as a last defence behind the Pease Pass of the

fairest bit of Scotland and the open road to Edinburgh.

Even peaceful transportation

appears to have been a formidable business through this pass. It sounds like

a huge practical joke that when a large sum of money had to be forwarded to

Edinburgh in the fifteenth century, it was despatched in penny and twopenny

pieces. "For God's sake," wrote the embarrassed English envoy to Scotland,

in despairing accents, "send silver and gold on the next occasion."

CartIoads of pennies toiling through the Pease Pass and the miry tracks of

Lothian to the Scottish capital has its humorous side.

The whole parish of

Cockburnspath, with its deep ravines and its varied surface, from the rich,

red tillage lands upon the cliff plateaus to the wild upland pastures of the

Lammermoors, is both picturesque and interesting. The oak seems to thrive

prodigiously in some of the deans, while in that of Dunglass the beech trees

have grown to a great size. The wild cliff scenery of the St.. Abb's

promontory, as earlier noted, is only modified as it descends to the mouth

of the Pease Dean. Beneath the red sandstone cliffs beyond this is a small

colony of fishermen, while in the village itself, half a mile inland, the

parish church, part of which is very old, possesses a most amazing circular

tower. There is a good inn here, too, a thing worthy of note in this

country, and the limited resources of the little village are taxed, I

believe, to the uttermost in the holiday season by visitors from Edinburgh.

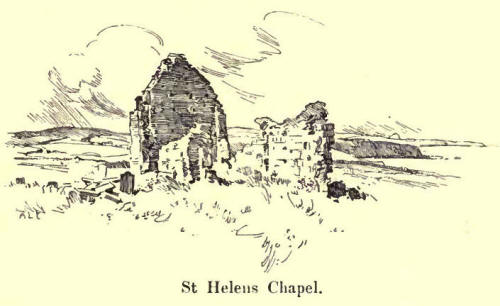

But before going actually down into East Lothian, I must not forget the

quite pathetic-looking ruin of the little chapel of St. Helens set in a

lonely spot near the cliff edge. It was once the church of the long extinct

parish of Oldcambus, and is supposed to be of Saxon origin, though so rude

and rough it might be anything. It was dedicated to St. Helena, mother of

Constantine the Great, and its erection is associated with a time-honoured

local legend, which relates how three daughters of a Northumbrian king,

terrified at the sanguinary conflicts then waging in that ancient Saxon

kingdom, decided to seek refuge in some quieter region to the northward. So

setting sail with their attendants, and heading their barques for the Firth

of Forth, they were constrained by stress of weather to put in behind the

headland of St. Abb's, where they found safety and hospitality in the Priory

of Coldingham. In gratitude for both these good things they each determined

to found a chapel, dedicating them to the respective saints through whose

good offices they believed their deliverance was owing. So

"They They all

built kirks to be nearest the sea,

St. Abb's, St. Helen, and St. Bee.

St. Abb's upon the nabbs, St. Helen upon the lea,

But St. Ann's upon Dunbar sands

Stands nearest to the sea."

But what is most impressive

about St. Helens, the only one of which any stone is standing, is, perhaps,

the old graveyard. Utterly

neglected and unkempt, out of the tangled grass a number of inscribed

tombstones rise amid the wreck of others which lie around shattered or

tilted at all angles. The earliest inscription I could read was 1646.

Another was to John Laune, weaver of Pepperton, born in 1698 and deceased in

1783, with his wife, who died in 1740. From this forlorn and long-abandoned

burial-ground above the sea there is a fine prospect of the low red cliffs

of Fast Lothian, with their green caps curving away towards Dunbar, the Bass

Rock, and North Berwick Law, in vivid contrast to the blue of the sea and

the white lines of the insurging tides that even in fair weather find their

breaking point far from shore upon the reefs that line this inhospitable

coast. |