|

THE coast of Berwickshire

forms a striking and aspiring interlude between the low shores of

Northumberland and East Lothian. Of those qualities appealing both to the

eye and the heart that lift these rugged Northumbrian shores far above the

level of the typical low-lying crumbly frontage that most of East Britain

presents to the North Sea, I have written a good deal elsewhere. Of how East

Lothian redeems its comparative lack of stature in this respect, I shall

hope to say something later in this book. No Southron, to be sure, nor

indeed very many Scotsmen outside the neighbouring districts, know anything

of the coast of Berwickshire. But that means nothing, save that it gathers

from such indifference the further distinction of aloofness from a restive

world, which so well becomes a coast-line that for many miles is awesome

enough in summer calms and positively terrific of aspect when waging its

solitary conflicts with the storm. Yet the world, and that, too, in its

thousands, roars past a section of it, along the very cliff edge, on leaving

Berwick. Such passing glimpses as are caught here, however, are but a faint

indication of what lies northward, when the train has swerved inland to wake

the echoes of the bosky Lammermoor glens and, after twenty breathless miles,

to leap out into the rich red sea-coast plains of Lothian. I doubt if the

passenger takes much note of all this. For my part, I have never lit upon a

friend or acquaintance who has gathered any conception of the sixty miles

between Berwick and Edinburgh from his Northern railway journeys. One might

fancy that the passing glimpse of the fishing hamlet of Burn-mouth, lying

several hundred feet in a cleft of the red cliffs below the train windows,

would catch even a vacant eye, or, again, that the winding wooded valley of

the Eye, with the wayward humours of that delightful stream playing

hide-and-seek for miles along the railway track, would in the course of

years acquire some kind of recognition. It seems strange, too, that the

beautiful tangle of the Pease Pass, which gave Cromwell so much trouble,

with its flowery glades and leaping torrents and overtopping bulwark of

purple moorland, followed by the sudden burst into the plains of Lothian,

radiant in its matchless fertility between the Lammermoors and the sea,

should leave no memory, whether at the end or beginning of so notable a

highway so often travelled. Probably all this is not generally regarded as

being in Scotland. At any rate, it is merely the Lowlands—infelicitous term

of vague, misleading import to the average south countryman, and not

supposed t.o be worthy of notice. Our friend is on his way to Edinburgh and

to the Highlands, which are all mountains and, in fact, alone signify

Scotland, so far as he is concerned. The Lowlands are all flat, and do not

count except vaguely for those who still read Scott and "take in" Abbotsford

on their way to the north. They contain counties the names and situations of

which are the despair of the Southron, who may know Inverness-shire as well

as Switzerland ; names that will always prove a tower of strength in those

geographical encounters which sometimes overtake the unwary wight in the

disguise of a parlour game.

I forget what famous debater it was who used to

drive the last home-thrust into the vitals of a Parliamentary opponent by

addressing him after his second title of Baron Clackmannan, an unfair ruse

which always, it was said, brought down the House and left the luckless

Baron smitten for the night beyond repair. Perhaps the motorist who riots

abundantly at certain seasons on the North Road, which road keeps intimate

company with the railway along these windy cliff edges and through the

Arcadian glens that Iead to Lothian, gathers something more of the quality

of the way. But, after all, neither type of passer-by concerns us, who have

not got to lunch at Edinburgh, nor yet sleep at Perth.

The Great North Road, which leads straight out

through the bounds of Berwick, those half-dozen square miles of farming land

filched from Scotland and assiduously "ridden" every year by the Berwick

burghers as if to flaunt their ancient triumph, should of a surety provide

the most callous wayfarer with something to think about. It is a bleak

stretch, to be candid, this half-mile span of terrace that for some miles

spreads from the cliff edge to the long slope of Halidon Hill and Lamberton

Moor and bears both road and railway northward. Nor is this amiss. For it is

a region of stern as well as of splendid memories, of slaughter as well as

pageant, and it is infinitely to our advantage that we can look all over it

unobstructed by woods and country houses, howsoever gracious in their place.

The long narrow strips of tillage, of grain, or hay or roots that follow one

another from the road to the cliff edge far upon our way would not claim

elsewhere any more notice than as a bright foreground to a boundless blue

sea, flecked with the sails of craft from a half-score of fishing villages

But the commonplace acres gain really some dignity of association when you

remember that they are the individual holdings of the four hundred and odd

hereditary freemen of Berwick. Even the huge sweeping fields of grass or

barley that climb in their rather sad, unadorned economic fashion the

fateful Hill of Halidon, though in truth they need no further story, gain a

little added interest from the fact that they belong to the historic

corporation of that town. It is good, too, to be able to look far ahead

along the wide open road to the famous Lamberton Toll Bar, the Gretna Green

of the Eastern Marches, where another blacksmith or the like tied up as many

runaway couples as crossed the Solway; which, by the way, if for a quite

different reason, is no more the international boundary, though nearer to

it, than is the Tweed here. But these are mere trifles of yesterday, and

Lamberton is incomparably greater as an ancient trystina-place than Gretna,

though the schoolboy in the Antipodes is familiar with the one and probably

no one in Hampshire ever heard of the other. For Lamberton saw many an

Anglo-Scottish pageant. Margaret of England, daughter of Henry VII., was met

here when, as a girl of thirteen, she proceeded northward with unprecedented

pomp to marry the gallant Scottish King, who a dozen years later widowed her

at Flodden Field. Two thousand nobles and gentlemen, riding three abreast,

escorted her to the Old Kirk which once stood at Lamberton, and there handed

her over to an equally gay company from Scotland, who carried her northward

to Edinburgh. 'There were ladies as well as cavaliers on horseback in this

fair company, which is minutely described by John Young, Somerset Herald,

with their jangling bells and persons arrayed in cloth of gold, and horses

frisking in trappings of the same. The Princess herself, in attire laced

with gold and precious stones, was carried in a litter surrounded by

attendants mounted on palfreys. Pavilions were pitched at Lamberton for each

degree, where with more wassail, such as Lord Dacre, Governor and Warden of

the Eastern March, had already indulged them with at Berwick, the merry

travellers made "great chere"; no less than six hundred of them going on

with their Scottish friends to make another night of it at Coldingham. And

how about Coldingham and its worthy monks and villagers, one might well ask,

when this swarm of gilded locusts settled on it; or did they, as was

probable, levy handsome tribute on their wealthy visitors?

Those were surely great times for country folk !

In the intervals of killing or being killed they had no end of spectacular

compensations. Fancy the Royal Family, half the House of Lords, all the

chief Cabinet ministers, bishops, generals, and admirals, blazing in jewels

and radiant apparel, camping out on your village cricket ground! James I.,

too, here first entered upon his kingdom, being met with ceremonies worthy

the occasion by the great ones of the English Border. Mary Stuart, in the

thick of her troubles with the truculent, self-seeking nobles that buffeted

her in such pitiless fashion about southern Scotland, rode on one occasion

to the hill above on her way to Coldingham. She was apparently impelled by

mere curiosity for a distant view of the famous town. But the news had

reached Berwick that she was hovering near, and the gallant Sir James

Foster, then Governor, gave orders for all the great guns to lift up their

voices on the new ramparts, and himself repaired with forty horsemen to the

Bounds. Here he met the Queen with Huntly, Murray, Lethington, and Bothwell,

and five hundred horse, when they all rode up to the top of Halidon Hill,

and the great guns of Berwick, two miles away, roared all that afternoon and

all that night in honour of the hapless and immortal charmer.

Charles I., on his progress to Edinburgh in

1633, after ten days at Berwick, was met at the Bounds by an amazingly

numerous and brilliant company of Scotsmen. Six hundred mounted gentlemen

from the Merse alone, were here, relations or dependents of the Earl of

Home, in green silk doublets with white scarves, and formed but a small

portion of the loyal array, which included most of the nobility and gentry

of Teviotdale and the three Lothians.

But this will never do! We might stand at

Berwick bounds and call up whole centuries of royal and famous pageants,

from William the Lion onward. Lamberton Toll is now represented by a couple

of humble dwellings, apparently quite unconscious of the significance of

their site, facing each other over a lonely bit of highway ; though one of

them, I believe, was once the actual blacksmith's shop which did such a

roaring matrimonial trade in comparatively recent days. There is an air of

melancholy and inconsequence about the once famous spot that to the dreamer

of dreams is not unwelcome. Little is to be seen from it but the hill of

slaughter, rising abruptly inland, where breadths of seeds or barley wave

and turnips flicker in the summer breeze, while the white curving road

trails away to north or south. Gulls from the neighbouring cliffs, but a

couple of fields distant, scream and wheel from England into Scotland, and

from Scotland into England, back and forth, or follow in long restless files

the track of a hind's plough as he turns the red soil of the Corporation

acres. A group of women workers, picturesque in their regulation garb of

blue blouse, pink neck-cloth, and short linsey skirts, come cackling betimes

along the road, or a mournful pair of professional roadsters shamble

southward, shaking the dust of Scotland and its sterner poor-law methods

from off their feet no doubt with joy and renewed designs upon the more

long-suffering ratepayer beyond the Tweed. Motors, branded with the brand of

remote counties, throb past at intervals and fly the Bounds with joyous

unconcern, and little heed or notion that they are raising classic dust.

It was hereabouts that the old road to Edinburgh

left the line of the present one, and climbed up past Lamberton Manse and

the now vanished kirk to the long lofty plateau of Lamberton Hill. Upon this

far-spreading common, renowned in Georgian times for one of the chief Border

race-meetings, lay the Scottish army, while on Halidon, a lower continuation

of the same ridge, towards Berwick, Edward III. drew up that army which was

to avenge his father's unforgettable defeat at Bannockburn. Lamberton Common

is now a delightful mile or so of gorse, bracken, and sward, lifted some 700

feet above the sea, whence you may look out over half southern Scotland, and

more than half Northumberland, while Halidon has been long enclosed and

tamed to the plough. But there is a dip between the two hills, and the

Regent, Archibald Douglas, who commanded the Scots, forgot the precepts of

the dead Bruce never to attack the English in a pitched battle, and forgot

it at a moment when his enemy was in great fighting trim, and furthermore

occupied a strong position.

Edward was investing Berwick, then in Scottish

hands, and articles of surrender had already been signed for an early day,

provided that the city was not in the meantime relieved. This, however, was

just what Douglas and the Scottish army now essayed to do. There was not

much strategy about the battle, and none of the old writers have found very

much to say about it except in regard to the slaughter which ensued. I am

afraid many readers will be surprised to hear that Sir Walter has celebrated

it in a metrical drama, and no doubt for its very paucity of outstanding

detail, borrowed the well-known Gordon-Swinton scene from the later affair

at Homildon. One famous incident, however, preceded the battle and augured

badly for the Scots. For one of the Turnbulls, a gigantic Scotsman,

accompanied by a furious mastiff, strode forth from the ranks and challenged

any warrior in the English army to single combat. Whereupon stepped forth

one Sir Robert Benhale of Norfolk, a man of prowess and great skill in arms,

though of only moderate stature. He disposed of the mastiff's attack by a

single blow, and, after a brief encounter, sliced off Turnbull's right arm,

and then, according to the current etiquette of such proceedings, removed

his head. The Scottish

infantry attacked uphill and were repulsed. The cavalry got mired in a

swamp, and their curiously fashioned horseshoes are frequently to this day

ploughed up, one being in my own possession. It was the old story of the

English archer, now just arrived at the zenith of his fame and skill, whose

terrible volleys were again and again too much for even the valiant North

Briton. It was here as at Homildon Hill, within easy sight of the crest of

Iialidon, forty years later. Whether these archers, like the others, came

from the Welsh Marches, the nursery of the English bowman, I know not, but

it matters nothing, the result was equally fatal. The arrows flew, says an

old chronicler, "like motes in a sunbeam, and no coat of mail could

withstand them." And so also King Edward, in Sir Walter's drama:-

"See Chandos, Percy. Ha' St. George! St. Edward

See it descending; now, the fatal hail shower,

The storm of England's wrath, sure, swift, resistless,

Which no mail coat can brook."

And to Percy, who exclaims that it darkens the

sky and hides the sun:-

"It falls on those

shall see the sun no more.

The winged, the resistless plague is with them.

They do not see and cannot shun the wound.

The storm is viewless as Death's sable wing,

Unerring as his scythe."

It was soon a rout. Only

seven Englishmen fell, says one account, while the Scottish loss is quoted

by various writers, after their hyperbolic fashion, at from 14,000 to

56,000. The stricken host was pursued all the way to Ayton, four miles

distant, and were cut down apparently like sheep, for the entire route, we

are told, was strewn with corpses.

"These men might well

see

Many a Scot lightly flee,

And the English after priking,

With sharp swerdes them stryking."

The slaughter was so great

among the Scotch nobility that the English vainly flattered themselves with

the prospect of no more Scottish wars, since no man capable of leading an

army appeared to be Ieft alive.

Bannockburn seemed indeed to be avenged, and the

triumphant Edward left a sum of money to the nuns of a Cistercian house then

standing at the foot of Halidon Hill, for a perpetual celebration of his

famous victory. The convent, the nuns; the vows of eternal pćans in Edward's

glory, and masses for the innumerable dead, have long vanished in dust and

fantasy, and the bloody, corpse-strewn track of the hapless Scots to Ayton,

which we may now follow, has been washed by ten thousand storms, and turned

over and over by a thousand ploughs.

But Burnmouth, the first gash

in the red cliffs north of Berwick, and that in truth a mighty deep and

narrow one, is well worth the trifling detour from the highway, if only for

a glimpse of the hamlet clinging to the base of the cliff, where from the

heights above there appears no space for what is in fact a whole community

of fisherfolk. It is well worth the steep descent of three or four hundred

feet, by the rough road that gives these hardy sons and daughters of the sea

access to the upper world. Or failing that, there is a grassy platform more

than half-way down which exposes in a way that an artist would surely seize

upon, this really uncommon and quite exquisite picture of a Scottish fishing

village. At any rate this vantage-point comes back to me from a summer

evening not long ago, when the sea was at its bluest, the overhanging cliffs

at their ruddiest, the greenery which hung over their summits and even crept

down their steep sides at its greenest. The red-roofed cottages, thrust into

the cliff-foot or perched about on rocky knolls covered with drying nets,

sent their wreaths of smoke straight upwards in the moveless air, for the

boats had just come in and suppers were no doubt impending. Short-skirted

women were carrying baskets of fish ashore upon their bent backs, for the

males of their kind, when they have beached the boats, hold that their part

in the domestic economy is ended. The gulls swung screaming from side to

side of the great cleft, or floated far below upon the glassy tide that

exposed every rib of the submerged reefs which pave the whole of this

inhospitable shore. For even here, a fishing station, the only refuge for

craft too large to beach is a small artificial harbour, where three or four

herring smacks were on this occasion idly lying.

Nobody would ever dream of suggesting that North

Britain, on either side of Tweed, can pride itself on the osthetie quality

of its inland villages. So it is perhaps just as well that in the

agricultural districts villages are comparatively scarce, the hind and his

family being generally quartered in those rows of low, red-roofed cottages

that cluster round the great farm steadings, and redeem them in some measure

from their rather uncompromising utilitarianism. There are exceptions,

however, and Ayton is one of them, as if conscious that first impressions

count for much, and that some effort is demanded of the first village upon

Scottish soil encountered by the northward-bound stranger. It is but fair to

admit, however, that there is no sign of self-consciousness about Ayton,

unless a large handsome modern kirk at its outskirts, set amid all the

mellow surroundings of grove, stream, and well-tended graveyard that graced

an ancient predecessor, count for such; while within this same predecessor,

it is interesting to remember, was held at least one Anglo-Scottish

conference of import to both kingdoms.

Nature has done a good deal for Ayton, and the

castle perched amid its nobly timbered parklands above, that has been for

all time associated with it, has done perhaps more. The approach to the foot

of the wide ascending village street touches the romantic, for it is made

over a bridge of a single arch thrown across a deep rocky chasm, where,

smothered in foliage, the pellucid waters of the Eye make gentle music.

Below this again they continue to burrow with complaining voice through

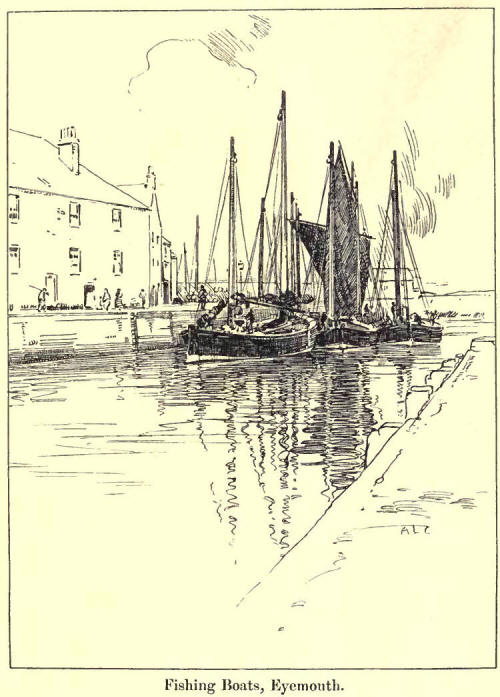

three more miles of woodland to the sea at Eyemouth, a little fishing town

of picturesque environment and of much note in that portion of the outer

world concerned with herrings, mackerel, or cod. The castle entrance, too,

stands near the bridge in all that pomp of massive Gothic red sandstone

architecture with which the great Scottish Border mansion is apt to

emphasise its dignity, and when, as in this case, such lordly portals are

overshadowed by stately timber, the effect is admirable.

Nothing of particular note or antiquity stands

out in Ayton village. Helped, however, by its pleasant site, its wide

sloping street, and its quite tolerable dimensions, it has an air of

old-fashioned dignity and consequence that is assuredly lacking in most of

its neighbours. Like every other place with a church and a castle on this

great highway, Ayton has a lengthy chronology and is steeped in historical

incident, which it would profit us nothing merely to tabulate. The present

castle is modern, but no less baronial in aspect for all that—a red

sandstone pile of the typical Scottish type with the characteristic French

affinities. It is beautifully placed high up amid a wealth of verdure, and

altogether so conspicuous from the railway that even our much apostrophised

friend on the Edinburgh mail must acquire in time some acquaintance with it.

It has broken its family as well as its structural links with the past,

which is as chequered a one as you would expect from a Border castle. Surrey

destroyed an early edition of it in the reign of James IV., when he

"continually bet it from two of the clock in the morning till five at

night," and after sparing the garrison, "razed it to the playne ground."

This was in pursuit of the Scottish King, who had espoused the cause of

Perkin Warbeck and raided Northumberland and Durham till, if I remember

rightly, the more tender hearted Pretender, unused to Border amenities,

protested against such wanton ravage. James, says the chronicler Grafton,

lay supinely within a mile of Surrey at Ayton and saw the smoke of the

bombardment. He sent heralds to the Earl offering him single combat with the

town and policies of Berwick as the stake. Surrey replied that Berwick was

the property of the King his master, and not his own to wager away, but

declared himself to be highly honoured that so great a monarch should make

such flattering proposals to a "poor Earl." He awaited, however, the attack

of the Scottish army, till both sides, having exhausted the resources of

that "tempestuous, unfertyle, and barrein region," went their homeward ways.

Surrey would be surprised if he could see the present-day agriculture of the

" barrein region " whose many towers he " razed " on that particular

expedition. So, I might add, however, would a modern south country farmer.

Avton may in a manner be said to form the entry

into that projecting block of Berwickshire which is cut off from the rest of

the county by both main road and railway, that together leave the coast at

Burnmouth and together meet the sea again at Cockburnspath. The old name of

"Coldinghamshire" which roughly covered it might be conveniently revived for

our brief purpose here. Indeed the county, besides its two natural divisions

of the Lammermoors and the Merse, might for purposes of lucidity be

accredited with this as a third one. For it is made up of a fragment of both

the others, and, with the modern road and railroad for a base, forms a

triangle, the point of which is St. Abb's Head, while either side is washed

by the North Sea. The coast sides are each some dozen miles in length as the

crow flies, the base nearly twenty. Eyemouth lies just within it, beneath

the southern horn of Coldingham Bay, which forms indeed the eastern side of

the triangle, and, though fearfully rugged and broken, is comparatively

low-lying. The northern side of the triangle from St. Abb's Head to

Cockburnspath is an unbroken barrier of savage, inaccessible cliffs with

practically no human life in their neighbourhood.

The considerable village of Coldingham, with its

famous abbey, is virtually in the heart of what I shall make free, in the

phrase of the ancients, to call Coldinghamshire, as Hexharn, Norham, and

Bamburgh, with less geographical cause, at any rate, carried the like

honour. The whole triangle, and more besides, like the clearly defined

"shire" of Hexham, was no doubt held in one way or another of the abbey.

Indeed the term Coldinghamshire is as old as the Saxon period, and its

limits were clearly defined Iater on by William the Lion. But as antiquaries

admit themselves baffled by the enigmatic surveys of that energetic monarch,

his primitive landmarks having no doubt disappeared, we need not worry about

such things here, but confine the ancient and convenient term to the limits

described. Coldinghamshire displays a variety of character and scenery that

many a region of its size, trumpeted by railroads, exploited by newspaper

essayists, and laboured at great length by guide-hooks, might envy. Its

eastern half is largely filled by grouse moors and wholly flanked by the

weirdest and most imposing sea-coast that Britain presents to the North Sea.

Upon Coldingham itself lies the atmosphere of a great lire-Reformation

church centre. In Eyemouth and St. Abb's village are most felicitous

examples of the important and the primitive Lowland fishing villages

respectively. Around Ayton and in the western part of the " shire " is the

opulent landscape already alluded to, while the deep woody valleys and

ravines of the Eye and Pease, with their glittering streams, strike yet

another note.

Coldinghamshire owes its qualities to the fact

that it is in great part formed by the seaward extremities of the wild and

lofty range of the Lammermoors. Starting, in name at least, from the deep

channelled country south of Edinburgh, through which the Gala and Leader run

to Tweed, and thence forging eastward to the coast, this great heath-clad

barrier completely severs Lothian from the Merse and Tweeddale, and is in

short the outstanding physical feature of the Eastern March of Scotland.

The road from Ayton to Eyemouth which skirts the

castle is a. short hour's walk, , and well worth doing, if only for the

intimate terms upon which it so frequently places you with the last and

perhaps the most beautiful three miles of the Eye's course. The little river

terminates its career in a remarkably abrupt transformation, within a few

hundred yards, from limpid cascades tumbling over mossy rocks in the

seclusion of inviolate woodlands to a deep channel where fifty or sixty

large fishing smacks may often be seen densely wedged between stone wharves.

The architecture of Eyemouth is undeniably depressing, though quite a number

of summer visitors put up with its sombre aspect for the charm of the rocks

and the sea, the cliffs and the coves which lie around it. For the town has

long outgrown the promiscuously picturesque collection of red-tiled,

white-walled cottages that makes the more primitive fishing village of this

ancient kingdom of Northumbria from the Forth to the Tyne pleasant to

behold. Immense stacks of herring barrels were piled up on the wharves when

I was last there, and a communicative aboriginal, with his hands

suspiciously deep in his pockets, who may, for aught I know, have been the

self-appointed orator of a taciturn breed, and not much more, gave me the

figures of a contract (for Russia, I think), which were of an imposing kind.

Fish-curing employs the lasses of Eyemouth, and their haddocks are quite

celebrated. A century

and a half ago, when the first pier was built at Eyemouth, Berwick received

a disagreeable jar. It seems that the monopoly so long enjoyed by that port

had emboldened its traders to treat the neighbourhood in rather high-handed

fashion. So the lairds and farmers concerned with sea-borne freight, legal

or illegal, turned with alacrity to this new outlet. Thirty years ago

Eyemouth was overwhelmed with a disaster such as has never probably in

modern times smitten a little fishing port, no fewer than 129 of its hardy

sons being drowned in a single storm, and most of its fishing fleet

destroyed. It has enjoyed, too, among some readers of Scott an adventitious

reputation as the scene of the immortal and resourceful Caleb Balder-stone's

raids for the replenishment of his master's empty larder and the saving of

his master's honour at the grim fortress of Wolf's Crag. As some eight

miles, much of which is rugged cliff edge, divide Eyemouth from Fast Castle,

undoubtedly the inspiring original of Ravens-wood's storm-beaten tower, one

must reluctantly forego all temptation to include any of the characters in

that great tragedy among the local genii. St. Abb's indeed would have a

prior claim if precise topography was applicable to the famous drama. But I

think that any one who had tramped afoot between that village and Fast

Castle in broad daylight would abandon all attempt to connect its fortunes

with those of this gruesome stronghold, or to imagine Caleb toddling down

there at night and returning betimes with a lean hen for his master's

supper. Coldingham,

some four miles away, lies, as already noted, where the lower and the higher

regions of its shire meet. It is a place of no infrequent pilgrimage for the

people of Edinburgh and the Eastern 'larch generally, and of resolute

antiquarians, of course, from much farther afield. Traps of assorted kinds

meet those slow train: on the main line which stop at Reston Junction and

bear away on most fine summer days a moderate company of tourists over the

three miles of fine undulating highway that bisects the shire and leads to

Coldingham. Adjoining the village, which, by the way, is another welcome

exception to the prevailing North British type, are the remains of the

abbey. The only important and conspicuous portion extant is the original

choir, for the excellent reason that it has been repaired and preserved for

the purposes of a parish kirk, while the other more or less fragmentary

relics of the once great monastery occupy the well-filled and well-kept

graveyard. The

monastery was founded in 1098 about two miles from the site of the primitive

establishment of St. Abb's. This last is attributed to Ebba, daughter of

Ethelbert, King of Northumbria, and sister to the pious Oswald, who under

marvellous circumstances, as some will remember, won the victory over the

heathen hosts at Heavenfield, near Hexham. At all events, Ebba retired here,

before the appointment of St. Cuthbert to the bishopric of Lindisfarne.

Legend tells of this saintly lady escaping from enemies who had made her

captive near the Humber, in a boat, and being safely and providentially

deposited beneath St. Abb's Head, which from this incident derived its

present name. Here Ebba remained in the convent she founded in thankfulness

for her escape, and together with her novitiates, being no doubt unversed in

the ritual and discipline of conventual life, she sent for Cuthbert, *ho,

lately risen from an obscure shepherd boy in the Lammermoors, was now Abbot

of Melrose. The opportunity of being by the seaside for the first time was

seized upon by the holy man, according to Bede, for inventing a new kind of

penance. For when Ebba's flock were all wrapped in slumber he would steal

down to the lonely shore and stand for the whole night up to his neck in the

water engaged in prayer and praise till the time approached for the regular

morning devotions. An innate of the establishment, stirred by curiosity at

these midnight excursions of the pious abbot to follow him and to become a

secret witness of his proceedings, himself reported this to the historian.

He also affirmed that when the saint came out of the water after his long

immersion, two sea-lions (seals) followed him, warmed his feet with their

breath, and dried them with their skins, after which they received

Cuthbert's benediction, and retired again into the deep. Ebba's foundation

continued to be the scene not merely of supernatural marvels, but of

sensational human performances. Once when a Danish raiding party were on the

shore, and the nuns feared for their chastity, they sliced off their noses

and upper lips, which so disgusted and enraged the intending ravagers that

they burnt the building and the nuns within it. This appears to have

happened about the year 870, and was the second and apparently final

destruction of the monastery. The first, according to Bede, was soon after

the death of Ebba, and was a visitation of God, long before seen in a dream,

upon the loose living of the inmates. For this, like most of such Saxon

houses, was in two sections, for men and women respectively, an abbess

presiding over both.

But the priory of Coldingham has only an uncertain connection with the

ancient foundation on the headland, and its chequered tale is modern history

compared to the weird chronicle of the other. It was founded in 1098 by

Edgar, King of the Scots, or of some of the Scots, after his victory over

the usurper Donald, and dedicated to St. Cuthbert for full value received,

if the visions of a Scottish King after dining with the monks of Durham can

be attributed to saintly inspiration. St. Cuthbert himself on this occasion

was the nocturnal visitor to the King, then on his way to recover his

kingdom, and guaranteed that if he carried the Durham banner before him, the

victory was as good as won. So Edgar borrowed the cathedral banner of St.

Cuthbert from the monks and caused it to be borne before his army, a

proceeding which fully justified the promise of the saint, and so

intimidated the enemy that numbers of them changed sides on the spot and

thereby assured the victory to Edgar. In the joyful and grateful mood

natural to his triumph, the King founded the Priory of Coldingham,

introducing thereto Benedictine monks from Durham, as was only right, and

endowing it handsomely with manors. He furthermore laid a yearly tribute to

his new priory on all the inhabitants of Coldinghamshire for the greater

advantage of his own soul and that of his father and mother, brothers and

sisters, a means of salvation that must strike our modern notions as

singularly mean, and as attributing to the Deity a remarkable absence of the

judicial instinct.

So Coldingharn flourished and became the most

powerful monastery between Berwick and Edinburgh. Among its earliest

possessions were many well-known places in the Merse, like Swinton, Lennel,

Earlston, Edrom, and Stitchell, where in due course it erected churches and

established parish boundaries much as they stand to-day. To follow the story

of Coldingham would be to labour the whole stormy sea of Scottish history.

Its position may be referred to, however, as singular—that, namely, of a

Scottish monastery ecclesiastically associated with Durham. More than one

King of Scotland endeavoured to alienate it, James Ill, more particularly,

who lost his life in the attempt. For the Homes, ubiquitous and powerful in

Berwickshire for centuries, and indeed all-powerful in the fifteenth

century, regarded it as their particular care, with the ultimate result that

the King fell in battle at Sauchieburn. His son, however, annexed Coldingham

to the Scottish Crown and placed it under the Abbey of Dunfermline. Several

of the priors in its later days, being members of the great, ever-factious

Scottish families, came, as was inevitable, to violent ends. Hertford in his

devastating march of 1545 set fire to the buildings. Then came the

Reformation, and in 1560 the monastery was dissolved. It had entertained in

its day almost every one who was anybody in Scotland, and in 1648 Cromwell

completed its long list of distinguished visitors, and at the same time,

upon the capitulation of the Royalist garrison, who had fortified it against

him, terminated its physical existence by blowing up all but the two sides

of the church, and undermining a tower which fell later. The memory of Queen

Mary's stay here, like the memory of everything else associated with that

hapless lady, who has so captivated the imagination of posterity, is perhaps

the most familiar in its story to casual acquaintances, and we have already

described how she came here from Lamberton with a great company. Whether the

Queen herself slept at the priory or at Houndswood, four miles away, still

vexes the soul of the antiquary, while a farmhouse near the latter place

called Mount Albion is supposed to commemorate the spot where she mounted

her white palfrey for the homeward journey.

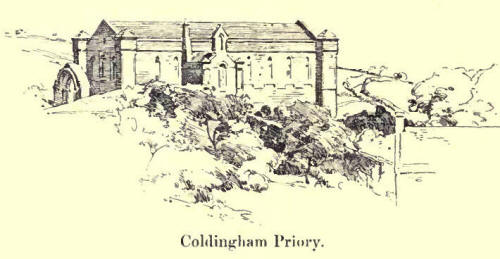

The original church, as the visible remains of

walls and the foundations of others discovered during the restoration

testify, was a large one, consisting of a central tower, a nave ninety feet

long, with aisles and transepts, the latter having eastern aisles or

chapels. The choir, of equal length with the nave, was aisleless, and was,

in fact, the church we see before us to-day. The whole building was used

freely as a stone quarry by the natives of Coldingham in old days. It is

fortunate that the heritors of the parish had both the sense and the taste

to make some reparation half a century ago for the ravages of their fathers

and grandfathers and restore the choir as the parish church—that is, to

build a west and a south wall upon the old foundations on to the north and

east sides, which were still perfect, and to roof them in. They were

assisted by the Crown, which perhaps ensured a structural harmony that

neither the period nor the locality might have been wholly trusted to bear

in mind. A curious English reader may possibly say to himself, "And what is

a heritor?" for the Scottish Church is a subject upon which the average

Southron of intelligence is complacently in the dark. Nor, probably, does

occasional attendance at a Highland Free Kirk in August shed much light upon

the darkness. The heritors, then, to waive technicalities, are, speaking

generally, the substantial men of the parish, whether owners or occupiers.

They are responsible for everything practical connected with the Established

Church of Scotland. Their body, unless voting is required, [Occasionally,

but less often I believe than formerly, two or more selected ministers

officiate in turn, and the choice between them then falls upon the

congregation.] elect the minister, and they are responsible for his salary.

The Scottish tithe is not fixed on a term of years' sliding scale of the

price of grain, as in the English Church, but each year the market price is

settled by a jury, presided over by the Sheriff, who meet and discuss the

matter from the standpoint of their own experience. Mr. Henderson and Mr.

Thomson (without the "p," if you please) quote the prices obtained at

Berwick for their barley, or Messrs. Deans and Logan assess the average

value realised for wheat at Dunbar or Haddington by some such personal and

doubtless sufficiently equitable method. The tithes are collected and paid

to the minister on the responsibility of the heritors. He does not have to

collect his dues like a landlord after the fashion of his English brethren,

though they come, of course, from the same sources, alike inherited from the

ancient pre-Reformation Church. Stay-at-home Scotsmen may marvel that this

last crumb of information should be accounted worth while imparting. If they

knew us in our home they would understand it to be quite urgently so—that

is, if English folk generally were very much interested in things outside

their immediate orbit, which is not, of course, the case. Those who are will

not need telling such elementary facts about the Church of Scotland. Those

who are not—nine out of ten, that is to say—will not in the least care to be

told, but continue to cherish a vague conception of a nation of dissenters

dominated in religious matters by ministers and elders whose ferocious

sabbatarianism is partially redeemed by the wealth of good stories of which

they are the genial heroes.

The style of the work in Coldingham Church is

very beautiful, being elaborate transition Norman. The exterior of the north

side shows an upper storey of eight single-light lancet windows, divided

from one another by broad shallow buttresses. Each window has deep

head-mouldings, springing from banded circular shafts with floreated

capitals. The lower storey, to use an expressive but unprofessional term,

consists of an arcading merely, of Norman arches arranged in couplets. The

same arrangement is practically continuous round the east end, the other

original portion of the church, while the two restored sides of course

correspond externally. At each corner is a slender square tower, barely

higher than the walls, with a low pointed cap. The roof is a low flattish

gable, and the building at first sight, even to an eye familiar with

remnants of mediaeval churches, is undeniably perplexing.

Within the building there has been no attempt,

in the restoration of the two vanished walls, to reproduce the elaborate

beauty of their ancient predecessors, nor indeed could the worthy heritors

of the parish have been expected to put their hands so deep into their

pockets as this effort would have entailed. Nor does it really much matter ;

the beauty lies in the work, its singularity and antiquity, not in the

building as such, since it is a mere fragment of the original, shorn of its

accessories, and without its proper complements. An open arcade, in the

thickness of the wall, is carried round on a level with the windows, making

a kind of triforium, sufficient for perambulation. The faces of the arches,

which are in couplets between the windows, are deeply moulded, while the

arcading of the lower compartment is extremely rich and ornate. That the

pewing and modern fittings are those of an unadorned Scottish village kirk

may have passing interest in the contrast between the unreformed

Presbyterian attitude towards beauty in Divine worship and that of their

ancestors. Two or three mortuary stones of early monks survive. Outside, a

solitary Norman arch, a relic of the south transept, is all that is

conspicuous, though the remains of the walls and foundations of the

monastery buildings are in part plain enough. About a century ago the

supposed skeleton of an immured nun was found in a niche in a part of the

walls that was being removed.

Now you may find a Scotsman in any part of

England, but a southern Englishman other than a domestic in a lowland

country village is an amazing curiosity. I have only encountered such a

spectacle once in my life, and that, too, in the surprising situation of

beadle to a Scottish kirk. For on repairing to the cottage where I was

informed that functionary at Coldingham had his abode, I was confronted by a

young middle-aged south countryman, and upon my astonished ears, attuned for

many weeks to the Doric accents of the Lowlander, there fell the

unmistakable and more dulcet notes of a west-country Englishman. Our friend,

it transpired, was a native of Gloucestershire, and, to his lasting honour,

had volunteered for the South African war, when, drifting into a Scottish

corps, he had returned home with his companions-in-arms to share in their

well-merited honours as a Scottish hero. A likely situation offering itself

on the disbanding of the corps, he had proceeded from that to the beadleship

of this Scottish kirk, and in addition to the acquirements demanded by that

semi-sacred office, had gathered those elements of medieaval ecclesiology

that in this particular one were in frequent demand. The transition from a

west-country trooper to a Scottish Presbyterian official struck me as

altogether delightful, but I did not, of course, betray my appreciation from

this point of view, particularly as I seemed to detect a becoming sense of

gravity in my versatile cicerone. I merely asked him how he got along, to

which he replied, "First rate." I touched gently on the difference in

ritual. "It ain't very different from our own, sir." After all, no more it

is nowadays, assuredly not for an honest, simple soul unvexed by traditional

accessories. Indeed the porch of a Scotch parish church would go far to

reconcile any sound Anglican to trifling discrepancies within doors. For

here are all the familiar notices fluttering on the walls that speak so

comfortingly and eloquently of Church and State, of one venerable

rallying-place of social and religious order, one link with the past still

intact from the raging of schismatics, the onslaught of socialistic dreamers

and schemers. Here are the familiar lists of game-licence holders and

ratepayers, the latest royal proclamation, the notices of parish minister or

Territorial colonel, which, whether in Scotland or in England, always seem

to me so pleasantly if delusively suggestive that all is yet well.

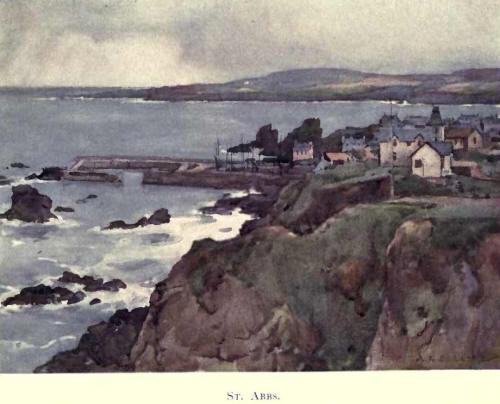

A mile of lane leads you from Coldingham to the

rocky cove where the quaint and characteristic fishing hamlet of St. Abb's

lies tucked beneath the first uplifting of that tremendous headland. Here,

as everywhere else on this inhospitable shore, the rage of the sea is held

back at one point by a massive breakwater, behind which a sheltered harbour

gives refuge to the red-sailed smacks and open cobbles that the village

contributes to the great fishing fleet of the North Sea. Away to the

south-east spreads Coldingham Bay, rocky and reef-ribbed, but the one

low-lying interlude of the Berwickshire coast, with Eyemouth in the neck of

its further horn. Farms and habitations lie thinly scattered behind it, and

here and there a smart summer residence, whose owner is almost certain to

hail from Edinburgh. To the north-westward, on the left hand is a mighty

wall of old Silurian rock falling sheer into the sea and thrusting out huge

fragments to meet the waves. Beyond is chaos and a long succession of

horrors from the sea-going point of view. It would be a calm sea indeed that

would tempt any roving craft landward till it reached the Lothian coast.

Two or three terraces upon the high ground, with

offshoots straggling over the broken declivities seawards, comprise the

village of St. Abb's. If its architecture is not idyllic, the whole air of

the place, fortuitously cast by nature in so rugged a setting, makes this of

less consequence. Coldingham is the annual resort of a few quiet summer

visitors from Edinburgh, who, with the exception of the owners of some

private villas, must be possessed of the happy uncritical temperament that I

am quite sure pertains to the middle-class Scotsman (or perhaps I should say

Scotswoman) in this particular. Another handful of still more adventurous

people of the same type perch themselves at St. Abb's, where the

accommodation is of a far more al fresco description. But if rocks and sky

and sea can anywhere make up for narrow quarters and ingenuous cookery, they

have here their reward. The fishermen in such sequestered havens, with the

freshness of their absorbing and daring life still untouched by contact with

a vulgarising world, are themselves worth cultivating, and far better

company for a sane being than negro minstrels or brass bands. The Scot of

the sea, like his fellow of the Northumbrian coast, has no touch with the

Scot of the land. For generations they have lived apart, though the barrier

of late years has weakened, and local ethnologists, as in Northumberland,

will trace them to different stocks. The Gaelic Scot of the western coast,

such as the Englishman generally sees, and that we all hear a great deal

more than enough about, is both a fisherman and a farmer, and conspicuously

inefficient at both. The Teutonic Scot of the east is either a first-class

fisherman or a first-class farmer (or rather farm labourer, a profession in

these parts far above in standing and in comfort the level of the western

crofter). But he is rarely both, and his respective ancestors have nearly

always been in the same trade. The last occasion on which I spent a few

hours at St. Abb's, striking evidence was exhibited of the peacefulness of

its inhabitants—proved, so to speak, by negation. I was standing on the high

terraced road looking down upon the harbour, where a smack or two were

landing their freight and crew, when of a sudden I became aware that the

village was in a state of electricity. Fisher wives and fisher girls,

abandoning their brooms and ovens, burst from a score of doorways and

gathered on the many points of vantage commanding the little harbour,

cackling loudly with that peculiar note of satisfaction which with the poor

suggests that something exhilaratingly unpleasant for somebody else is going

forward. Other natives of both sexes, and also visitors with winged feet at

the bare thought of something happening at St. Abb's, scurried at best pace

down the rocky ways towards the sea. I thought perhaps a boat had upset, and

vainly scanned the then placid waters of the little rockbound bay for some

sign of misadventure. A heated matron, however, came panting by at this

moment, and in response to my inquiry pointed to the quay below, and with

such breath as she could spare explained in three fateful words the cause of

all this upsetting. "Yon's a fecht!" And taking note of the direction

indicated, I espied a turmoil of the nature of a Rugby football scrimmage on

the pier, which through my glasses revealed the fact that most of the

purging group were not themselves combatants, but wrestling to keep the

peace between the actual gladiators. Anon the word "police" was tossed up

the village from lip to lip, and in due course the Coldingham policeman,

summoned by telephone, dashed into the town on the top gear of his bicycle,

and descended to the scene of the now apparently terminated encounter. When

he breasted the hill again in company with a dishevelled, shame-faced being

the town learned, probably with much more disappointment than relief, that

peace was once again restored. Its disturber, I gathered, was a fisherman

from Eyemouth of militant temperament, who, having landed with a drappie in

his e'e, determined to clean out the town, and, beginning with the first man

he saw on the quay, at once met his match. Hence the prolonged encounter and

this stirring ten minutes for St. Abb's. |