|

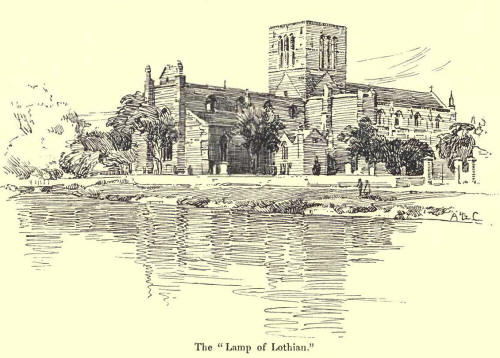

LUCERNA LAUDONIAE, the Lamp

of Lothian, as Fordun in the fourteenth century styled the beautiful abbey

church of Haddington—a felicitous appellation that has in a manner clung to

it for all time—is the only spectacular attraction Haddington offers to the

casual visitor. It is of cruciform design, fashioned of rich red freestone,

which, a tradition similar to that associated with many other mediaeval

edifices maintains, was brought from Garvald, six miles away, by passing it

stone by stone along a line of men. The church, of Gothic style, is all that

remains of a Franciscan monastery founded in the thirteenth century. The

nave measures 200 feet from end to end, the transept about half as much, and

there is a fine massive central tower 90 feet high. The western portion of

this beautiful building has been always used as the parish church. The rest

of it was in the hands of the workmen on a recent visit. It rises above a

large well-shaded graveyard outside the town, and near the banks of the

Tyne, altogether a site in harmony with its stately proportions and its

abounding memories. Whether it was gutted by the English during Hertford's

raids in that singular interlude between the English and Scotch

reformations, when the former, figuring as Protestants, threw down the

altars of Lowland papists, or whether the Scotch reformers, in their

iconoclastic orgies after 1559, took the chief hand, I do not know. There

seem to have been at one time

as many as fourteen altars in

the church, and it was always the burial-place of men of birth and might and

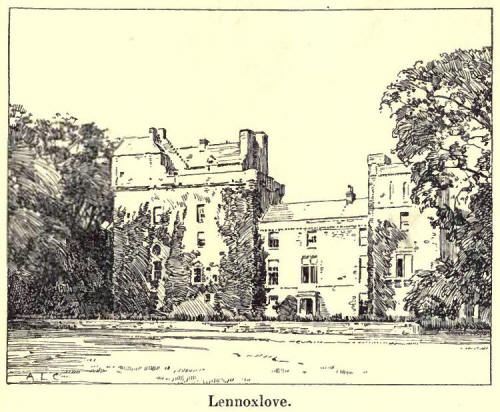

piety. Chief occupants of all, perhaps, are the Maitlands of Thirlestaine

and Lennoxlove, an immense and gorgeous monument having been reared within

the church to the memory of John, Lord Maitland, Chancellor of Scotland, who

lies here in effigy beside

coffin stands a stone urn

proclaiming that it contains "all the intestines, except the heart" of John

of Lauderdale. Perhaps the last-mentioned article was found wanting! Almost

within the shadow of the church, and just across the Tyne, John Knox was

born. The very house, with dubious authenticity, is pointed out. He attended

the Grammar School here in popish times, and as he was notoriously reticent

about the first forty years of his life, it is assumed that the creed

against which he raged so violently for the rest of it, hitherto satisfied

him. The Earls of Bothwell were Lords of Haddington in his day, and an old

house with a round tower and steeple turret remains in a side street as a

survival of their fortress. But neither for the teeming story, lay or

ecclesiastical, of this ancient town, nor yet for a purview of its few

remaining architectural fragments that bear witness to it, is there space

here. With the long Anglo-Scottish struggle; with the civil wars waged in

the cause of religion; with the bloodless, but bitter theological cleavages

that have thrilled Scotland in later times, and of which the average

Englishman knows less than nothing;—in all these things Haddington has

played a prominent part. And I have had the hardihood to pass over all its

stir of drum and trumpet and pulpit, and at the sight of its shrunken corn

market become wholly absorbed in its other atmosphere, and dropped

uncompromisingly into reminiscence! There are people, too, I am quite sure,

who would discard all these things, and all the men and women of the ages

who have fought, or made pageants, or preached, or foregathered here, and

hunt out the house where Jane Welsh lived, before she married the sage and

prophet of Ecclefechan.

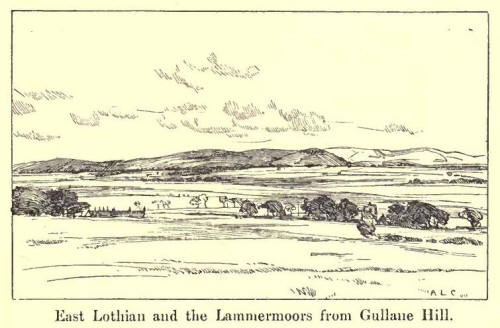

Leaving the Edinburgh road to

pursue its broad way through the eastern part of the county into MidLothian,

and climbing the Carleton hills by the one that leads north to the

sea-coast, a notable bit of country spreads out below. This is that low

undulating and comparatively treeless tract which bulges slightly out into

the Firth. On its western edge the woods of Gosford and Luffness mantle

about the sandy flats of Aberlady Bay. Its eastern limit may be roughly

defined by the wide woods of Tynninghame, which, through the prescience of a

long ago Earl of Haddington, now sweep in luxuriant beauty along the edge of

the Tyne's mouth, and give annual pleasure to a multitude besides their

owners. A hundred and fifty years ago much of this smooth remorselessly trim

country was marsh. It is now, and has been for at least half that period, a

perfect picture of scientific farming on a great and generous scale. It is

not such a picture as would captivate the artist. On the contrary, he would

ramp and rave at such homesteads, planted here and there upon the waving

chequered plain, and thrusting up their tall red engine chimneys above the

scant fringe of timber. This is not Dunbar red land, but a heavier soil for

the most part, of but moderate original fertility. It has been farmed,

however, in like manner, and as if every square yard were precious: though,

perhaps, an equally moving stimulant is the Lothian farmer's hatred of

ragged edges, of crooked lines, of straggling, unkempt fences, of thicket

and other nests of weeds, and all things that incidentally make for beauty.

One might add, too, an all-pervading prejudice against hedge-row trees and

open ditches; though for that matter the whole of this country was

tile-drained before most of us were born. As a last word to the occasional

reader, who may care for such things, virtually the whole of this district

is arable. In old days there was not an acre of permanent pasture outside

the policies, but now there seems to be a field or two here and there laid

away to grass. Present rents average about £3 an acre. Potato-fields are

still conspicuous here, and come once in the six-course shift, as of old,

instead of twice, as is frequent on the superior lands of Dunbar. It is

through this open country, between the Garleton hills and the Firth, that

the main line to Edinburgh runs. And here, at last, is a point on it

familiar to hundreds of southerners. For out among the great turnip and

wheat fields stands the forlorn little junction of Drem, unchanged, and

apparently unconscious of the flight of time. Here the southern golfer bound

for classic shores changes trains for North Berwick, near by, or gets into

his fly for Gullane, still nearer. In former days the Peffer burn silted

through this water-logged country. It has now this long time been

transformed into a shallow canal, running straight for miles between high

banks, catching the drip of the tile drains from the prolific fields. I

remember being present at the testing of an exceptional yield of swedes in a

field upon its banks, which, for those whom such details might concern, may

be noted went approximately thirty-five tons to the acre ! But the point is

that an old man employed in the operation, told me he well remembered this

very field as part of a marshy waste, held as an uncanny country by the

children for the will-o'-the-wisp which scared them on autumn nights. The

rich colouring in summer and autumn of the fields, and the red flare of the

sandstone tile-roofed steadings, geometrical in design, all give the

landscape a character of its own. I well remember, too, the look of this

stretch of country on still, murky November afternoons, when the summer

colouring had vanished and left the land sear and brown, when the smoke from

half-a-dozen steam ploughs and as many threshing engine chimneys within easy

sight, drifted about in the deepening gloom, giving out an oddly conflicting

sense of stir and a queer impression of beef and bread manufacture at high

pressure, rather than the normal calm of a conventional winter Arcady. And

through it all, in weird contrast, came the almost ceaseless cackle of wild

geese and the stray pipe of passing wisps or golden plover. The steam

ploughs have almost gone. It is, perhaps, without parallel for a great

mechanical invention, widely adopted and once hailed as an epoch-making

contrivance with unknown potentialities in the greatest of industries, to

snuff out. But this is practically what has happened to steam cultivation in

parts of Europe and America, and for reasons which the reader, who has

probably had more than enough of agriculture, will care little.

But the summer sun is

supposed to be shining on these pages. And after all, this remorseless

landscape, where neither the violet, the primrose, the blue bell, the wild

rose, nor the honeysuckle, nor the may nor the elder, nor any of the

commonplace wildings of the passing season, find footing to grow or

opportunity to put out their blossoms, has another side to it. For it is a

land of magnificent distances, and moreover abuts upon an always rocky, and

distinguished seacoast. Along this last, too, there is for the most part a

pleasant interlude, where the ruthless austerity of East Lothian agriculture

pothers out into sandy commons and rolling dunes, and blowing woodlands. And

here disports itself in villas, mansions, and cottages, clustering thick or

sparsely scattered, a joyous population, who, as all the world knows,

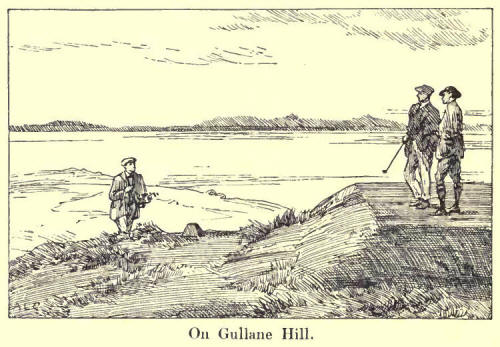

worship (on week days) one all-exacting deity. From Aberlady Bay and Gullane

Hill, whose broad green slopes look down upon it to North Berwick, however

diverse their paths may be on the first day of the week, they all lead the

same road on the other six. Most of the able-bodied between four and seventy

years of age among a fluctuating community of several thousand souls pursue

the bounding core-ball with tireless assiduity over nearly a dozen different

golf courses, and have, for the most part, no more truck with the country we

have been wandering in than they have with the moon. This stretch of

littoral must not be confused with the many courses, or sets of courses, on

the west or northern coasts of Scotland, of championship class or otherwise,

that are familiar names to southern ears. They are not classic soil ; this

is. Those others belong to the modern epoch as much as Sandwich, Harlech, or

Portrush, and more so than Westward Ho or Hoylake. They were almost as alien

to their atmosphere as any in Kent or Ireland, and, as much as these, are

the result of the modern development of the game. But here upon the Firth of

Forth, we are in the real old golfing section of Scotland, though the

procession of courses that on either side of it now line the shores of Fife

and Lothian represent, of course, a state of things bearing small relation

to that of thirty years ago—thirty, forty, sixty, or a hundred years for

that matter. The small developments in detail of the game up till then are

of trifling consequence compared to the chasm which divides any of those

periods from this one in the number of followers and the attention bestowed

on golf throughout the civilised world.

This is assuredly classic

soil, not merely because North Berwick lies upon it, and more historically

famous Musselburgh, shorn of its glory and attraction, lies virtually within

sight, but from the fact that golf has been for hundreds of years a familiar

thing upon the coast. What a difference, though, in degree! I think as a

southerner one may fairly account it a privilege, in view of all that has

happened, to have played over Gullane links after an interval of forty

years. The fact, too, of having followed the game more or less through all

its changes and expansion in the South makes such isolated memories of these

old conditions seem rather precious. Special trains from Edinburgh and

streams of motors from everywhere now bring players to the three courses

laid out on and about the broad low hill of Gullane, to that of Luffness at

its foot, or to the adjacent championship course of Muirfield. While on a

sixth arena, of more modest compass, infants of all ages and both sexes

engage with as much gravity as their elders. A mixed foursome, aggregating

perhaps thirty years, may be seen holing out on one green, while on a

neighbouring tee an urchin, as recently hatched, is addressing his ball with

preternatural gravity. Such wee folks are usually incapable of playing

ordinary games by rule and to order. None of those spasmodic evolutions

quite irrelevant to the business, nor clamorous interludes which distinguish

the very small boy wielding a bat or delivering a ball of any kind are

visible here. They appear to play what was once called in its callow days of

golf-understanding by the southern press, the "old man's game," with all the

gravity of an old man. This may be due, in part, to the discipline and

sporting spirit, which it is apparently the sacred duty of the attendant,

mother, nurse, or governess, in this atmosphere to instil. The solemnity and

attention to green etiquette of these midget golfers under the eye of their

mamma, who will doubtless play her round in the afternoon, is an engaging

spectacle, not to be witnessed, for lack of opportunity, on any English

courses known to me. Gullane course in the dim days when, as a light-hearted

cricketer from the far south, in the company of my young Scotch friends, I

first miss-hit gutty balls round it, had just, I think, been increased to

fifteen holes. Those

old swan-necked drivers with long springy shafts were much more

disconcerting to the player of other games than the stiff-handled

short-headed weapon of a later day. I have still a relic of these East

Lothian days in the shape of a driver of the most approved type and quality.

It appears to strike the modern as a positively uncanny thing. The ball had

to he "swept" away with these old implements, not hit. I do not think the

system of right arm and tight right-hand grip, followed and successfully so

by some tremendous drivers and quite good players, would have been possible

with those more exacting clubs. At any rate, I am quite sure that so then

unorthodox a style would have created amazement on Gullane Hill in the days

of old. In regard to the mother course of this now celebrated group of

courses at Gullane, in the early 'seventies I seem to recall it as very

little played over upon ordinary days. I can still, however, with the eye of

memory see very distinctly one or two couples of well-known local farmers

breaking the solitude of the course—one of them particularly, a man of years

and repute, in all ways playing a strong game, in a black, low-crowned,

chimney-pot hat. I can recall his long swing and easy style with great

precision, for the excellent reason that he was the first good performer I

had ever watched, and that, too, with the interest of a rather zealous

player of other games. It was then the fashion, and for nearly twenty years

afterwards, for Englishmen who caught a glimpse of golf in their Scottish

journeyings, and of many who had never even done thus much, to condemn it

unequivocally as an unthinkable pursuit, though a trifling handful even then

drawn by accident or curiosity to St. Andrews were caught in its toils. I am

almost sure, however, none were to be found at North Berwick or anywhere

else on the shores of the Firth in those days. For myself, I admit that the

very first sight of the game captivated me entirely, and am, on the whole,

thankful that the opportunity to wrestle with its elements on the old nine

holes at Archerfield, and rarely over the smoother swards of Gullane were

not too abundant. For there were other things at that time of life in that

country more useful and more spacious and more active to be done. A friend

and companion of those days, much longer, and more nearly concerned with

them, reminds me that on Saturdays and other holidays players from Edinburgh

used to muster in fair strength on Gullane Hill. But these things are, of

course, all matters of common knowledge among the initiated. Is there not

still the little round tower on the top of the hill, which was once the

headquarters of a close society of nine golfers, who just filled it at their

prolonged session ? The Round-house Club still exists as a somewhat

ex-elusive society, but expanded and detached from its original fortress.

Whatever may be the mysteries of initiation to masonry and kindred bodies, I

am quite sure they are as child's-play to those exacted in former days of

each newly elected member to the liberties of the stone tower on the hill.

Firstly, it was ordained that he should take a header into the sea, I think

in his clothes, off "Joveys' nuik," a well-known rocky point below the

links, and subsequently, by way no doubt of staving off any evil

consequences, it was incumbent upon him to drink a bottle of whisky to his

own check. From a weaker generation and a more inclusive company these

tremendous proofs of worth, I need hardly add, arc no longer demanded.

Standing to-day on Gullane

IIill, where the keen winds wage almost continuous warfare, to the despair

of pilgrims from the woody courses and sheltered greens of the gentler

south., things indeed have changed. All over the green waste, rolling from

Gullane old village to Luffness, and Aberlady Bay, the several courses wind

their intricate, be-bunkered, stretched-out lengths, peopled with men and

women plying the daily round. The puzzled conies scuttle, and the peewits

drubb and

cry as of yore, when all this was a lonely

warren and sheep pasture, and in the lower parts a snipe bog. Over the wide

shiny sands of Aberlady Bay, the far-receding tides still race, and in

autumn push before them great companies of curlews, knots, dunlins, and

oysters-catchers, of greenshanks and black ducks, of plovers, grey and

golden, and sandpipers; while from the fields at sunset, just as of old, the

wild geese come honking down to swell the nightly clamours of the shore. As

you wait on one of the higher tees with the patience for which popular

Scottish links are an admirable school, or, better still, on Sunday, when

the golf ball has ceased from troubling, and the noncombatants venture

fearlessly out from their lairs into the open, Gullane Hill offers a superb

and justly celebrated prospect. For it crowns a point of land from which you

can see the whole Firth both up and down, and at close quarters.

Westward beyond Aberlady Bay, and most

effectively at evening, when its dark rugged form is reared above the

fifteen miles of green and woody shore, Arthur's Seat, with the Pentlands in

its rear, springs nobly up against the crimson of a sunset sky. Smoke

wreaths curling around its feet and floating out towards Inchkeith

significantly mark the Scottish capital, while a blur of broken land and

narrowing waters hide the Forth Bridge in the very eye of the setting sun.

Those high-rolling hills, the Lomonds of Fife, and its far-stretching

village-studded shores, have been before us in familiar fashion again and

again in these pages. But here a dozen or so miles across the water, one is

placed on almost intimacy with the gracious southern bounds of that ancient

kingdom, which, as part of the later realm of Scotland, always seems the

complement as it were, in influence and civilisation, if not always in

agreement, of the Lothians and the Merse. You can here follow its shores

from Burntisland to Fife Ness, where the corner turns and the line of coast

runs up to St. Andrews, the other capital of mediaeval Scotland. There is

nearly always shipping, too, on the Firth, from the red-winged fishing

smacks of Leith, to the war vessels of all types that have now their havens

here. Turning inland

you have the spaciousness of the Lothian atmosphere to perfection. It seems

to matter little that the foregrounds are geometrical and trim, and lack the

mute invitation of most summer landscapes to their fields and woods, when

forty miles of the Lammermoors rise and fall in endless waves behind them.

Luffness House, embosomed in foliage above the Peffer's mouth, is a seat of

the Hopes, partly modernised, but of long story and tradition. The grounds

are surrounded by the traces of earthworks and ditches

raised in 1549 by the Scottish General de

Thermes, who erected a post here for intercepting supplies on their way to

an English garrison then quartered at Haddington. There are remains, too, in

a pointed doorway and fragmentary wall of a Carmelite convent. The fishing

village of Aberlady, near by, is redolent of old days, and with its many

red-tiled roofs is as mellow as the invincible austerity of Scottish

architecture permits the hand of time to make it. Aberlady made up its mind

that Napoleon had selected it for his landing place in 1804-5. Nearer

Gullane, and on the fringe of the links, is Saltcoats, in former days, like

so many of these large farms, a family estate, and the ruinous remains of

the old mansion still stand in the fields. The property was granted to one

Livingstone in the i\Iiddle Ages for killing a wild boar that had wrought

havoc in the countryside and defied all its heroes till this one encountered

and slew the public enemy. The property remained with his descendants till

the eighteenth century, and when it was sold the sword and spear that killed

the boar were still in the garret, and were purchased for a trifle by a man

in Edinburgh, who bore the family name. They are said to have been hung for

some time in Dirleton church. The present ruin is the remains of two square

towers, with a living room and a kitchen, a roomy fortified dwelling, built

by George Livingstone about 1590. The original pele tower was much older,

and before the grant on the wild boar account to the Livingstones, is

traditionally said to have belonged to the Knights of Malta. The present

condition of the building is due to the fact of its having been used as a

quarry in erecting the present steading of Seallcoats farm.

Gullane, a secluded enough village when I first

knew it, lying around two expansive greens, with a single inn, which then

sufficed for its golfing world, is now a town with a long street of shops,

several hotels, and a neighbourhood covered with private houses. Its ancient

name was Golyn, and within its parish was the now important village of

Dirleton. The remains of a mediaeval church in picturesque decay in its

midst must arouse ungratified curiosity in many passers-by; a roofless

ivy-clad ruin in the middle of an ancient churchyard. A semi-circular Norman

arch, dividing nave from chancel, almost alone survives as an assured

fragment of the original twelfth-century building, the remainder being, I

believe, of the Reformation period. For the rising importance of the rival

village had prevailed, and the church of Golyn was cast down in 1631, and

that of Dirleton erected to supply its place. Perhaps, too, the fact that

the glebe land was all buried by a sandstorm about this time had something

to do with the extinction of its ecclesiastical existence.

It is not surprising that Gullane has very much

more than turned the tables on Dirleton in recent years. Half-a-dozen sand

courses at its gates, and these only forty minutes from Edinburgh, would

alone make the fortune of any place that was given the opportunity and

reasonably encouraged by a railroad. But the bright-coloured, rocky shores,

with the sandy little golden bays and rolling commons, where the wild

flowers rejected of the Lothian farmer find a home, afford everything that

can be desired in seaside luxury for young and old; while on the

invigorating quality of the breezes it is not necessary to enlarge. There

are many charming houses, and bright gardens, too, have been created, in

spite of difficulties of wind above, and sand below. It is the most

wide-open place conceivable. You seem to see every bit of the sky all the

time, at all points of the compass, and for obvious reasons feel every wind

that blows equally. Gullane leans, moreover, towards the dry and sunshiny,

and the sun, though it does not often cause a man to tear off his clothing,

or desire to do so anywhere upon this coast, sheds a singularly radiant

light upon land and sea. There are a good few permanent residents, and a

greater number who reside for the six summer months, the men folk going to

and fro from Edinburgh, while still more, of course, come for briefer

holiday periods. English and even American golfers are constant visitors,

and, indeed, it would be hard to name a place where such a variety of

courses is offered, and consequently a comparative freedom from

overcrowding. The modern championship course of Muirfield adjoins the

village, and, unlike the others, is reserved for members. It is said to be

almost perfect golf for the scratch or plus player. As it all lies, however,

in a single large and rather level enclosure surrounded by a stone wall, its

general appearance is uninteresting and artificial in the highest degree.

Dirleton used to boast within the small orbit of

its earlier world that it was the prettiest village in Scotland. I see now

in slightly modified form, through the medium of the guide-book oracles,

that it reiterates the claim to a much wider public. This is not, to be

sure, a flight to any great a sthetic heights, but Dirleton, which has not

altered a bit, is assuredly a delectable little place. It mostly fronts upon

a village green, one side of which is occupied by a hoary fortress of

historic fame, beautifully embowered among foliage and gardens kept up with

assiduous care for this last half-century. The village dwellings, each in

their own gardens, though a trifle formal, look what they are, the creation

of a former landlord's pride and care. An admirable old inn, where the

little local golf club used in old days to sup once a year, and sup

formidably as regards accessories, has the place of honour. The kirk,

dignified but unbeautiful, stands retired from the green amid stately

timber, and the manse, still occupied by a minister of old celebrity on

links and rinks, lurks snugly across the road. The Iodge gates of the great

house to whose fostering care in the past this pleasant scene is mainly due,

open into its midst. The said mansion, Archerfield, a great square pile of

Georgian complexion, stands far back amid luxuriant woods, flanked by deep

belts of sombre fir that stretch away to the seashore in dark, solid, rather

striking masses. Alongside of them are the links: in the days I have so

often alluded to, a rough nine holes, now doubled, and assuredly the most

alluring little course in natural texture, and for other reasons, upon the

whole coast, though too short for serious rank among them.

Near the adjacent shore the rocky island of

Fidra rears itself high above the reef-fretted waves, and is now adorned

with an imposing lighthouse. To the east and west are two smaller islands,

the Lambie and Ebrochy, while the Bass towers beyond far out at sea. Between

village and seashore is a farm that was created out of almost pure

sand—hundreds, probably far more, of loads of its soil being exchanged to

their mutual benefit with that of a heavy-land farm two miles inland, by the

tenant of both. Such was the enterprise of the East Lothian farmer in the

great times ! Nevertheless, I well remember the fact that the seeding of the

spring corn was always followed by a period of anxiety, lest peradventure a

high wind should arise and blow the whole crop—seed, that is to say, top

soil and all—into the sea, or into the next parish, before it had taken

root, as more than once happened.

Such is Dirleton. But its castle is, of course,

the overwhelming attraction, and a favourite resort of golf-widows and

orphans, and other visitors from North Berwick. Portions of the towers and

walls remain, heavily festooned with ivy and all such kinds of foliage as

love to climb and twine about these old memorials of a truculent and bloody

age. But some great vaulted chambers on the ground floor are, perhaps, the

most interesting feature remaining. The gardens, with their bright display

of flowers and beautiful shaded bowling-green, though of no contemporary

significance, provide a most harmonious setting for the old pile, and vastly

enhance the charm of the spot. The castle was of considerable importance

throughout the whole bloody tale of Scottish history, and was constantly the

object of attack or defence in all the wars with England. Originally reared

by a Vaux in the thirteenth century, it was one of the castles that resisted

Edward I. in 1290, and was captured by Beck, Bishop of Durham.

In the next century it fell through an heiress

to the Haliburtons, and ultimately descended to the Ruthvens, one of whom

took part in the murder of Rizzio. James VI. with characteristic timidity

took refuge here for some time, when an epidemic was raging in Edinburgh,

and at the Gowrie conspiracy in the same reign the Ruthvens forfeited the

estates. That sinister being, Logan of Restalrig, whose concern with this

business we told of when at Fast Castle, had an eye on Dirleton, as a reward

for his service in the event of the plot succeeding. "I care not," he wrote,

to its owner and his fellow-conspirator, "for all the other land I have in

the kingdom, if I may grip it [Dirleton], for I esteem it the pleasantest

dwelling in Scotland." If he wrote this with the waves raging round him at

Fast Castle, one can well understand how his appetite was for the moment

whetted. At this Gowrie forfeiture it was granted to Sir Thomas Erskine, who

had come, it was said, to the assistance of the king at the critical moment,

and was now created Lord Dirleton. During the civil wars the castle was

captured by Generals Monk and Lambert, and finally dismantled. In due course

it was purchased with the adjoining property by Sir John Nisbet, the most

eminent lawyer in Scotland, at the close of the seventeenth century, whence

passing in the female line more than once, it is now with the Archerfield

estate the property of Mrs. Hamilton Ogilvie.

Scottish, even more than English lawyers, had

great facilities through the seventeenth, and yet more through the

eighteenth century, for acquiring property and founding families, and they

did not miss their opportunities. They were the nabobs of his time, says

Ramsay of Ochtertyre, who reports a favourite aphorism of one of them, a

comical Lord of Session: "Gear ill-gotten and well-hained will always last

against what is well come by but ill guided." Their rival nabobs at the

prodigious material rise of Scotland in the eighteenth century were the

returned East Indians, and doubtless also some West Indian planters too.

However, the fortunes of these last, whether acquired by dubious methods

from orientals or by slave labour from Jamaica and Rarbadoes, were, at

least, clear increment to their native country. That the intricacy of

Scottish law and the dumfoundering phraseology in which it revelled alone

placed the hapless layman caught in its toil at some peculiar disadvantage

we can well believe. Moreover, the fact of land being almost the only

security for ready money, prior to Scotland's industrial awakening, turned

lawyers into lairds even more frequently than in the sister kingdom. Indeed,

Sir Walter himself makes no little play on this subject, as we all know, and

is never happier than with those humoursome, long-winded limbs of the law he

has so inimitably painted.

North Berwick, in the ears of the world at

large, simply stands for golf, with the biggest of G's. Vaguely mixed up

with Berwick-on-Tweed, it may be, and indeed I well know is, but as regards

its supposed raison d'etre there is no confusion whatever. And this may seem

rather curious, since till comparatively recent times it had only a

nine-hole course. St. Andrews, as everybody knows, is in itself a place of

high distinction. North Berwick has structurally no distinction whatever. A

hard, sombre little fishing town, with the scant relics of an abbey, a due

share of the ruggedly picturesque though low-lying East Lothian seacoast,

and a fine view of the Bass and the Law is about all that there is to be

said for it. That whole streets of detached and handsome villas, and a mile

or more of even imposing residences scattered along the seaboard have sprung

up within my memory, is a fact of little abstract interest. It used to be a

modest but popular seaside resort from Edinburgh, and though still no doubt

on intimate terms with the capital, has now a far wider appeal. It has a

slightly aristocratic flavour, and is supported by the usual three classes

of well-to-do folk—the permanent resident, the summer resident, and the

holiday visitor. Its better houses, like those of Gullane, let furnished at

handsome rents—always by the month be it remembered, and not by the week as

in England. All well-to-do southern Scotland, who have not their own holiday

houses, go to the sea for one month or for two months, never for five,

seven, or nine weeks. It would be impossible—they could not be accommodated;

it would upset the letting arrangements of every house in the place. At

Gullane, for instance, the whole floating population depart on July 31st,

and an entirely new set come in till August 31st, when another general post

takes place. In apartments it is just the same. Unmindful of this

idiosyncrasy of Scottish life, I once scoured the far-expanded streets and

terraces of Dunbar, in a vain attempt to engage rooms for, say August 20th,

for a fortnight. But the dates, I soon discovered, were impossible. There

were plenty of rooms, and plenty of willing landladies, but those who were

empty, and those who soon would be, expected to let on September 1st for a

month, and preferred the bird on the bush to that in the hand. I came at

last to realise that my proposition was regarded as almost uncanny. If a

whole nation does the same, I suppose it is all right, and you get used to

it. But if unaccustomed to map out your time by lunar months, it comes as

something of a shock to be regarded by landladies as almost a suspicious

character for the mere expression of a desire to stay at a seaside, or

indeed, for that matter, at an inland resort, from the 20th of July or

August for a fortnight or three weeks. Hotels and the like, it is needless

to add, are not run on these cast-iron principles.

The original golf club of North Berwick was

formed in 1832, and consisted of fifty members elected from all over the

district. But the course belongs to the corporation, like most others in

Eastern Scotland, and is free to anyone at the usual payment - 2s. a day in

this case. The eighteen or twenty handicap man, as I have before remarked,

generally selects a crowded course, so long as it is a famous one, and what

satisfaction he derives from this method of procedure still remains, so far

as I know, a secret locked in his own breast. The etiquette of the Scottish

links is so rigid and the manners are so admirable, that even when he

habitually plays with his wife, who receives half a stroke from him, the

infelicity of his selection remains quite possibly concealed from his eyes.

The North Berwick course is much congested in summer, and constitutes, I

believe, a popular stamping ground for these misguided souls from all parts

of the country. That no ordinary calculation, even of an initiated and

discreet person, can render it safe to walk about on, I had speedy and

sufficient proof. But there is really nothing more to be said about a green

so celebrated in golfing literature, unless, perhaps, to note that a second

course has been opened within the last few years. The little harbour and the

rocks about it are characteristic of the coast, and the Bass here displays

itself superbly a mile or so from the shore, though the only access to it is

by a small steam launch, which plies from Canty Bay, two miles eastward of

the town, and has, I believe, a monopoly of the traffic. I was unable to

revisit it, owing to the incessant wind; for the difficulty of landing in

the single available spot is such that the trip is only feasible in calm

weather. The shape of

the rock, which rises 320 feet out of the waves, is singularly imposing, and

its sides are wholly precipitous, save where its broad back shelves down

into the sea at the landing-place. The interests are manifold, and cover the

centuries. Zoologically the thousands of solan geese or gannets, which have

found an immemorial home in its inaccessible cliffs, make the rock in this

particular unique. In old times these birds were accounted a delicacy,

figured upon the tables of kings, and fetched a high price in the market,

though rejected by the modern palate. The education of the young birds is

conducted on heroic principles. Stuffed to repletion by the parents with

poddlies, a species of cole-whiting which abounds in these seas, they become

encased in a thick coat of fat, and in due course are hefted unceremoniously

out of their nest, to fall into the sea below. Here they are supported

without upon the waves, and nourished within by their own obesity, till

their wings and natural instincts develop sufficiently to start life in

earnest. The birds, with whose nests the cliff ledges are crowded in the

breeding-season, are of course protected, the rock being private property.

Its history commences, like that of most such storm-beaten islands, with a

sixth-century saint—in this case St. Baldred, of notable name among the

missionaries of the north. He is said to have died here, and considering

that to this day the lighthouse people are sometimes confined to the Rock

for weeks together, one can well believe that this one, like so many others

on the coast of Britain, received the parting breath of the saints who

frequented them. Local nomenclature on the mainland still recalls the wonder

of St. Baldred's miracles. The Bass is indelibly associated, and for all

time, with the name of the famous family of Lauder. Though so prolific and

tenacious a breed that I have seen somewhere a list of thirty and odd

estates in South-Eastern Scotland, held in old days by different branches of

the stock, the Lauders of the Bass stand apart and by themselves, being

also—though I tremble as I make this statement, so ramified is the Lauder

lineage—identical with the Lauders of Lauder, whom we shall meet anon. The

first Lauder of the Bass became so by virtue of his heroic support of

William Wallace, the Rock being granted him by the Bishop of St. Andrews,

together, no doubt, with that territory on the mainland which his

descendants held with it. His son was a devoted follower of Bruce, and was

one of the plenipotentiaries who signed the treaties both of 1323 and 1327.

The family kept a grip of it, rejecting the money overtures, and defying all

other attempts of the Stuart kings to get hold of it, till very near the

time when it was purchased for the Crown in the reign of Charles II.

Valueless financially but for the gannets, it must have been strategically a

fine asset to a Scottish family in the everlasting struggle to keep place

and property. A chronicler of the house tells us that the family only

summered there in times of peace, living otherwise upon the mainland. They

were all buried in the old church of North Berwick, which has been gradually

consumed by the sea, till now there is but a fragment of it left upon the

sand. A flat stone in the centre of the green, near the old almost vanished

twelfth-century church, still marked the hereditary burying-ground of the

Lauders of the Bass eighty years ago, since which the encroaching sea has

obliterated the spot.

The Lauders shone both as churchmen and ambassadors. They provided Scotland

with several bishops, and were frequently governors of Berwick when it was

in Scottish hands. It was Sir Robert Lauder, "our Loveit of the Bass," as

James III. calls him, who had to conduct those waggon loads of pence, eight

horses to a load, in which Edward IV. sent the Queen's marriage portion,

through the rutty tracks of Lothian. The most eventful incident upon the

Rock during the long occupation of the Lauders, was the month's sojourn

there of James, son of Robert III. of Scotland, on his way to France for his

education. Eventful, because it was after sailing from there that he was

captured by the English, and detained in the south for nineteen years.

James's acquaintance with the Bass probably suggested the idea to him of its

unequalled advantage, from other points of view. For it was he who first

made use of it as a prison.

But its notoriety as a prison-house is, of

course, associated with the Covenanters, for whose benefit the Government of

Charles II. especially purchased it. Every good Presbyterian takes his hat

off to the Bass, or is expected to. The grim heroes who inspired the

resistance to the attempts of Charles and Lauderdale to impose the Anglican

Church, and particularly bishops, upon Scotland, were herded into the

unwholesome and gloomy prison, whose remains still speak vividly to those

who have read the blood-curdling accounts of the "martyrs martyrs of the

Bass." The Revolution of 1688 liberated such of them as survived out of the

thirty or forty who were here immured, and replaced them, as was only just,

with some of their former persecutors. And now ensued by far the most

dramatic episode in its whole story. Four of Claverhouse's late officers

were imprisoned, or one should perhaps say detained, here, for they were

obviously at large in June 1691. On one occasion, when the small garrison

were outside the fortified wall which defended the only accessible point,

loading coal, these Jacobite prisoners shut the gates on them, and were thus

in possession of the rock. They were joined by three or four ardent spirits,

and, having possession of the guns, were practically secure from any attack

that the authorities at Edinburgh could make upon them. Thus the situation

remained for months, and its sensational nature attracted other enthusiasts

for King James, till the garrison rose to sixteen men. They had boats and

were able without difficulty to seize provisions on different parts of the

coast. On one occasion a small Danish ship, quite ignorant of the situation,

came within close range of the guns, and was seized and plundered. For two

years the Government could do nothing but keep watch on the opposite shore.

At last they despatched two small war vessels

and another craft to watch the island more closely; but a French frigate

came to the rescue and drove them away. A man who had supplied the rebels

with provisions was captured, and, as a terrible example, was hanged on the

mainland, in full view of the rock; but its defenders scattered the

attendant crowd by a well-directed shot into their midst. Eventually,

however, renewed efforts by the Government to cut off supplies began to

tell, and at length impending starvation forced Middleton, their leader, to

offer terms. The envoys sent to discuss them, however, were entertained as

if supplies were no object, and contrivances arranged to make the garrison

appear much stronger than it was. Ultimately, after holding out for three

years, and by far the latest piece of British soil to yield to King William,

the Rock was surrendered. The garrison received their lives and freedom, and

the best of terms, as well as an uncommon meed of admiration from the whole

Jacobite world. The works on the Bass were soon after this demolished, and

about 1706 the Crown sold it to Sir hew Dalrymple, a great lawyer, whose

descendants still own it, together with the property on the mainland which

doubtless was the cause of the island purchase. At the end of Quality Street

a spacious old house with pleasant grounds relieves the sombreness of one

old portion of the little town, and has been usually a second residence of

the Dalrymple family, their country seat of Luchie being in the near

neighbourhood. The old Cistercian nunnery of North Berwick, founded in the

twelfth century, was a house of some importance. Several successive

prioresses were Homes of Polwarth and elsewhere, and James VI. seems to have

handed over the whole property to that family, who must have had on this

account, and for lands and favours no doubt bestowed by them, more title to

it than usually existed in the shameless scramble. The Scottish nobility,

however, would have been more than human if they had foregone their

opportunities, after the example shown them by their neighbours. And Heaven

knows there was nothing superhuman about the Scottish nobility of that day,

unless it was the activity they showed in keeping the pot of State

perpetually seething. But scant remains of the two gable ends and other

fragments standing near the present station are left of a house whose

forgotten glories Scott has caused to glimmer again in the deathless pages

of Marmion. The scene at the priory, when Fitz Eustace takes the unwilling

Clara from the train of the Abbess of Whitby into the toils of the hated

Marmion at Tantallon, will be one of familiar memory.

The parish church that was in use in my day is

now a ruin, deserted for a new one, but as a seventeenth-century building it

calls for no comment. Of the original parish church at the foot of Quality

Street, where the Lauders of the Bass were buried, nothing remains but the

porch and the font. It seems to have been used as a quarry for the

surrounding buildings. The promontory on which it stands was in former days

disconnected with the shore at high tide, and the interval crossed by a

stone bridge. This inconvenience seems to have been the cause of its

abandonment for the seventeenth-century church now in its turn deserted.

Seven miles out at sea is the low-lying rock, a mile in length, so

conspicuous an object at the entrance of the Firth, and carrying an

important lighthouse. My own recollections of a choppy passage to the Isle

of May, long ago, are too vague for serious recall, even if it were worth

it. There is nothing of interest but the fragments of a chapel, indicative

of the invariable ecclesiastical associations and significance of such

islands with monastic houses. In remote times, oddly enough, the island

belonged to the Abbey of Reading; and in later ones, James IV., who was an

indomitable sportsman, used to go there in a boat to shoot wild fowl.

Worth Berwick Law has of necessity provoked a

word of notice here and there on various pages of this book, as it is so

aggressively visible from everywhere, and whether from afar or near, so

suggestive of a freak of nature. One knows of many "Sugar loaves" in

Britain, detached from hill or mountain ranges. But this one has no remote

affinity with any range. It shoots up without any apparent reason from a

virtually level and extremely trim country of wheat and oats and turnips and

potatoes, to a sharp point nearly seven hundred feet high, that in mere form

would reflect no discredit on the Snowdon range, and put to shame any hill

on the Cheviots or the Lammermoors. The Bass, like a huge mastodon squatting

on the deep, is remarkable enough. The great whale-backed Traprain is

singularly isolated, though not extraordinarily out of place. But North

Berwick Law, which I always think of as the central figure of these three

curiosities that gaze across at one another, is far the most uncanny.

Witches astride of broomsticks flew over it, of course, as thickly as modern

aeroplanes, and among its various traditions is a curious legend, embalmed

in a later ballad, from which it appears that a Borthwick at one time owned

the Law, and "Abode in

his seaward tower

\Which looketh on to the German Sea,

A wild and lonely bower."

He possessed a lovely daughter, for whose favour

Willie o' Cockburnspath, and Murray o' Marshall were competitors to the

death. Just as they had arranged to settle the matter at the sword's point,

or at any rate settle which should not have her, the proud parent, hearing

of their intention, intervened on behalf of his daughter's outspoken

preference for the Cockburnspath hero, but only on the outrageous condition

that the young man should first carry his prospective bride to the top of

the Law, without letting down his burden. The desperate struggles of the

gallant with his fair burden, whose weight we have no means of estimating,

as he nears the top are graphically described. When at last, by superhuman

efforts, he achieves the feat, his "heart bursts" with the strain, and he

falls dead upon the summit, and the lady goes mad.

"There's a green grave on North Berwick Law,

And a maniac comes and sings,

And with the burden of her song

The valley 'neath her rings."

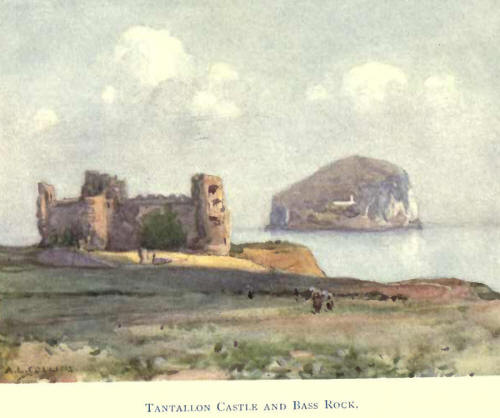

The coast rises beyond North Berwick into

tolerable cliffs, and upon the brink of one of them, just beyond Canty Bay,

stands the mighty ruin of Tantallon, that for distinction of pose as a coast

stronghold, is only inferior to Welsh Harlech and English Bamborough.

Though little more than a shell within, the

height and length of this, its curtain walls, spreading upon the landward

side from a central keep to two massive drum towers at the corners have a

most imposing effect; the more so as Scottish castles, numerous though they

be, are seldom large. Most people, perhaps, would come to Tantallon in an

exacting frame of mind, for the very flavour of its name will be either

vaguely or definitely significant of mighty men and great doings, and they

will not be disappointed. Only one side was vulnerable, the others falling

abruptly to the rocky shore. The wide green pasture over which you approach

the fortress on the landward side exposes its whole front elevation to great

advantage, as well as the form and circuit of the outer defences and

ramparts. As you cross the inner moat up to the gateway, where the falling

portcullis, it will be remembered, grazed the tail of Lord Marmion's horse,

as he dashed for the rising drawbridge, the bloody heart of the Douglases

confronts you upon the wall. The keep, through which entry is made, is

practically a shell open to the top. Inside this and the high curtain walls,

a large grassy area, once the inner court, and encroached upon, no doubt,

with buildings, spreads to the verge of the cliff

"Above the booming ocean leant

The far-projecting battlement,

The billows burst in ceaseless flow

Upon the precipice below."

Battlements and buildings have long vanished,

and a broad lawn, with the deep castle well in its centre, opens a fair and

verdant terrace to the sea, which rumbles amid the jagged red rocks far

below. Upon the north side only is the remains of a single building,

generally held to have been the banqueting hall. As a fortress, Tantallon

dates back to the twelfth century. It comes into the broader page of

history, however, when the Douglases first acquired it in the fourteenth

century. In the next one, however, the long struggle which this arrogant and

ambitious house waged against the Stuarts for the throne of Scotland, to

their ultimate discomfiture, found them stripped of all their possessions.

Tantallon, however, remained with the name, as it was granted to the only

bearer of it, the Red Douglas, who remained loyal to the king. Much more

familiar to posterity, however, was another Douglas, Lord of Tantallon,

Archibald Bell-the-Cat, otherwise Earl of Angus, who inherited in 1479. His

advice to James IV., while camped on Flodden Edge, to return while there was

yet time, and not to court either disaster or a bloody unprofitable victory,

and how James rejected it with such ill-considered words that the irascible

old man went back then and there to Tantallon in high dudgeon, is, of

course, a famous passage in history. Two of his sons, however, and two

hundred of his followers, fell on that fatal field. Another became Bishop of

Dunkeld, and wrote much poetry, including a translation of the Æneid.

Another, who became Earl of Angus, and head of the house, married his late

sovereign's widow, Henry the Eighth's sister, and mother of the infant King

James V., causing thereby no end of subsequent trouble. True to the

instincts of his stock, and further stimulated by his connection with the

Crown, Angus would be satisfied with nothing less than the supreme control

of Scotland. Ultimately young James and his stepfather came to blows, and

there was another Stuart-Douglas war. The king came himself to Tantallon,

with all those big guns with untoward names dear to the later Scottish

kings, and not famous, it must he added, for effective shooting.

The royal guns, at any rate, frightened Angus

out of Tantallon by the back stairway which the sea offered, whence he

sailed to England. They do not seem to have damaged the ten-foot-thick walls

of the castle seriously, as the king eventually purchased its surrender. The

Earl of Bothwell was now entered as Lord of Tantallon and its domains, but

his loyalty was of short duration, and ultimately Angus came back from

England, was reinstated, and acted as his brother-in-law King Henry's

representative in those schemes of his for marrying the infant Mary to his

son, and uniting the kingdoms. James V. was dead, Arran was Regent, and

Cardinal Beaton in high favour and influence. It was that brief day, too,

when a Catholic Scotland shuddered at the English heresies, and in any ease

profoundly suspected English schemes, even when statesmanlike and

well-intended as these perhaps were. Sadler, Henry's English envoy, found

things getting so hot for him, that lie was glad to retire to Tantallon,

while the irascible king at last lost patience, and proceeded

characteristically to vent his rage on those whom smoother measures could

not win. Ike threw over Angus and his Scotch friends, and flung his raiding

parties into Scotland under Eure, and in destroying Melrose Abbey, destroyed

at the same time the Douglas mausoleum. This maddened Angus and the

Douglases, who had their revenge at Anerum Moor, where Pittscottie says the

charge of the Scottish army was like the roaring of the sea.

The Douglases held Tantallon till the end of the

seventeenth century. In the meantime it had been besieged by the

Covenanters, and captured from the Douglas of that day, who held strong

prelatic sympathies. General Monk appears to be responsible for its ultimate

abandonment to the bats and owls, owing to the condition in which he left it

after a fortnight's bombardment. It was soon afterwards purchased by Sir Hew

Dalrymple, that same eminent jurist who acquired North Berwick and the Bass,

and still remains the property of his descendants. The castle is well looked

after, and is naturally the resort of numbers of visitors and of picnic

parties, upon whose cheerful festivities its grey walls, redolent of

unquenchable ambitions, of intrigue, arrogance, and boundless pride, look

down in grim significance. The clean sweep of the interior buildings, the

naked simplicity of the huge walls and gutted towers, which may be ascended

by partially repaired staircases, leave the mind of the visitor free to

follow its fancy into the truculent days of old. He will not be called upon

to undergo the mental torture—for I am sure it is torture to many persons of

sensibility without the architectural instinct—of following the intricacies,

traced by little more than their foundations, of ward-rooms, soldiers'

quarters, chapels, banqueting halls, kitchens, store-rooms, and the like.

These are not everybody's hobby, though they weigh on the conscience of many

who would like to be quiet and dream dreams. Instead of this they feel hound

to worry over ground-plans, and wrestle with measurements, and hang upon the

lips of a conscientious custodian, all of which intricacies fade into thin

air when they have paid him their shilling, and walked forth again into a

twentieth-century world.

But at Tantallon the visitor may with a free

conscience give himself up to the influence of the spot, unharassed by

fragmentary details that, it must be admitted, are at times

distracting—almost prosaic. He can feel, at least, the sombre shadow of the

mighty walls, and, soothed by the low roar of the waves beneath, can muse,

if he is equipped to do so, on the strangeness of this old forgotten world,

which lay practically at the mercy of the owners of such fearsome piles as

this. For a race as ready to serve two masters as was this branch of the

House of Douglas; an eyrie that swept as does this one the great wide-open

mouth of the Firth of Forth from St. Abb's to the point of Fife; that

offered an impregnable front to the land and commanded the sea upon its

rear, was ideal. This upstanding bit of coast, after leaving Tantallon and

turning southwards, gives way in due course to the flats of the Tyne

estuary, beyond which the traveller can get one more distant glimpse of the

old town of Dunbar; its woody hinterland, for such at this distance it

appears, rolling back to the dark wall of the Lammermoors, while far away

upon the seaward horizon, one behind the other, the lofty capes of St. Abb's

peninsula fall abruptly into the deep.

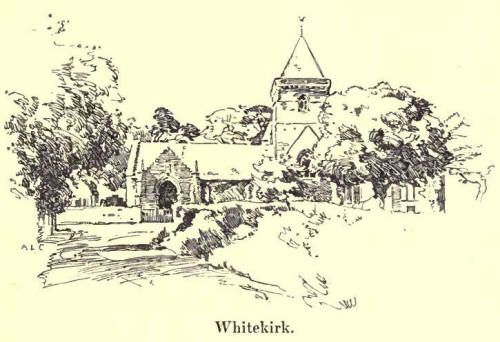

Here as elsewhere the foreground will make scant

appeal to the average pilgrim. In no long time, however, these waving

parallelograms that enclose the highest achievements of agriculture, give

way to what two centuries ago was held with good reason as one of the

greatest triumphs of forestry in the north. But before reaching the

Tynninghame woods, the fine old pre-Reformation church of Whitekirk,

standing high above some cross-roads and a small hamlet, in a spacious and

leafy churchyard, is passed by no one, and, indeed, is in itself an object

of pilgrimage to numbers in a country so despoiled of its ecclesiastical

monuments as this. A massive, red sandstone tower, with a heavily corbelled

parapet of late thirteenth-century date, rises high above a long low body,

consisting of nave and chancel, built mostly in 1439, while the porch is

apparently of the same period. The building would, I fancy, disconcert the

southern ecclesiologist at many points, but is interesting in its very

seeming discrepancies as they are the work of ancient and reverent hands,

not of eighteenth-century heritors and their masons. The east end has plain

step gables and a circular window, above which is an armorial bearing which

I could not decipher, and is, I believe, a mystery. To the north of the

church is a large tithe barn, a very rare survival in Scotland, at the west

end of which was once a pele tower. The minister tells me that this is

thought to have been the building which sheltered the pilgrims to the

shrine. The origin of

the church is interesting. There was a famous holy well here in mediaeval

times, which has now vanished. When Edward I. in 1294 was pursuing his

victorious career through the Lothians, Black Agnes, Countess of Dunbar,

fearing capture in that stronghold, took ship for Fife, but so severely

injured herself in embarking that she was forced to land on Tynninghame Bay.

Being here in great agony, and fearful of the English war parties, she was

altogether in a bad way, till a hermit appeared and persuaded her to drink

of this well, a proceeding which healed her bruises instantly. So on the

first possible opportunity, having proclaimed the miracle far and wide, she

built and endowed a church upon the holy spot. From henceforward the number

of pilgrims to the well and shrine from all parts was prodigious, as many as

15,000 coming in a single year. Adam Hepburn of Hailes added a stone arched

choir in 1439, but at the Reformation the pilgrim houses, of which there

appear to have been many, were pounced upon by a neighbouring laird, one

Sinclair, who used the material for his own purposes. These details and many

more were gathered by the late Sir David Baird of Newbyth close by, from a

MS. in the Vatican Library, which concludes its account with a lament that

the shrine was "beat to pieces, and that holy church shared the fate of many

more, and was made a parochial church for the preaching of heresy, and by

them called Whitekirk."

Presbyterianism has always been accounted, and,

indeed, has always accounted itself a democratic persuasion. The southern

Anglican, however, who has seen the glories of the old-time squire's pew

practically swept away by general consent, would be amazed at the spacious

dignity which still attaches in some Scottish kirks to the laird's spiritual

conveniences. At Whitekirk 'three large landowners are thus seated in

hereditary glory. The Tynninghame family have a roomy carpeted gallery,

furnished with some fine old chairs that the beadle informed me were 200

years old. The house of Newbyth have a raised pew, running right across the

cast end, where the altar would stand in an Anglican church—a pew of most

conspicuous dignity that would almost seem intended for a whole company of

deans and canons.

Tynninghame woods, which cover 800 acres along the shore of the Tyne

estuary, are threaded by drives, and are a great source of pleasure to the

visitors and others from Dunbar, North Berwick, and elsewhere. Historically

they are of singular interest. For their planting coincides with the very

dawn of Scottish rural enterprise, and was the first sign of what Scotsmen,

then accounted backward and slothful in such matters, could do if they

tried. The sixth Earl of Haddington was the pioneer in question, and

Chambers tells us that his wife was the inspiring angel, the young man being

hitherto wholly given over to sport, while his lady was devoted to trees.

This enterprising young woman, a daughter of Lord Hopetoun, thought her

husband might make better use of his time, and converted him even to

enthusiasm. Three hundred acres of wind-smitten, sandy soil were first

planted, to the entertainment, it seems, of the whole countryside. But the

laugh lay with his lordship and his zealous lady, when the trees throve far

beyond even their expectations, and now, after 200 years, are represented by

a portion of that fine seacoast forest known as Binning Wood. After more

planting Lord Haddington took up agriculture, which in the reign of Anne and

the first George, was dimly dawning as an industry worthy of the name in

Scotland. He planted belts of trees to break the force of the harsh winds

that strike the East Lothian coast, and imported farmers from Dorsetshire to

instruct the natives. "From these," he says, "we came to a knowledge of

sowing and the management of grass seeds." The notion of East Lothian going

to school with Dorsetshire might well have made the Hopes and Hendersons,

the Skirvings and Wilsons of a later day rub their eyes, and East Lothian

even then was less primitive than the rest of the Lowlands.

But as regards the Tynninghame woods, 400 more

acres of even worse land than the first planting were next ventured upon, on

the strength of the utterance of a German visitor, to the effect that he had

seen as worthless land growing fine timber in Germany. Though this tract was

practically bottomless sand, producing nothing but rabbits and whirs, the

experiment, to the amazement of the country, and the joy of this

enterprising couple, succeeded as well as the other, and completed the

stretch of forest, that may well be the pride of their descendants and the

delight of visitors. For Scotland, at the time these woods were planted, was

the nakedest land in Europe, and allusion has already been made to the

astonishment at its treeless surface expressed by English and foreign

visitors. As regards the agricultural awakening which went hand-in-hand with

the new zeal for afforestation, Ramsay of Ochtertyre gives great weight as

an epoch-making date in this transformation to the Jacobite rebellion of

1745;—not merely because it roughly synchronised with the general

commencement of effort, or, at least, of good intentions, but itself

contributed indirectly to the movement in the Lowlands. Wolfe, when he was a

young major and colonel policing the Highlands after the Rebellion, wrote

thence to a friend that a load of blackmail amounting to over £30,000 a year

had been lifted from the shoulders of the lairds and farmers bordering on

the Western Highlands. I recall the letter, which I have read in the

original, for what it is worth. But if Wolfe's figures were approximately

correct, the burden, even spread along an extended frontier, must have been

vexatious indeed, and at the hands of what this unsympathetic and

disrespectful young Whig stigmatises as "common thieves." This, however, is

parenthetical ; for whatever the measure of this tax, it was not the relief

from it, which must have been achieved a little earlier, but the wider

opening of the Highland markets, and the increasing demand in England for

their black cattle, that was the contributing factor to the improvement of

Lowland agriculture. For the Lowlands were a half-way house to the southern

markets. The forming of enclosures for feeding and harbouring the transient

herds not only improved a vast amount of land but opened the eyes of the

lairds and others to the value of stock for tillage purposes.

Ramsay's own property was in the Carse of

Stirling, and his experiences, personal or at first hand—information from

older men, for which he had the keenest scent—virtually cover the eighteenth

century. From the outer darkness of almost agricultural barbarism, that is

to say, to much more than the dawn of light. Indeed to vast accomplishments,

and to the lifting of rent-rolls by material improvements, and the growth of

intelligence, in some cases from £200 to £5000 a year! He gives us a vivid

picture, the more vivid because set down in such simple matter-of-fact

style, of the Lowlands generally in the earlier part of the century. The

run-rigg system is still in full swing: sour, undrained, unprolific lands,

miserable crops, cultivated with archaic home-made wooden implements,

dragged by straw ropes, sometimes actually tied to the tails of emaciated

horses. He shows us a peasantry and tenantry immovably wedded to their

pristine ways, darkly suspicious of any innovations, above all, if they came

from England, in which country the travelled Scotsman saw what then appeared

an agricultural paradise that filled him with despair.

Then he draws a picture of the gradual

awakening, giving the names, the characters, and the idiosyncrasies of the

various lairds who, returning from the south, took off their coats—in one or

two cases even literally—to fight the darkness, the sloth, the prejudice in

matters pertaining to the soil. Fletcher of Saltoun, who was, of course,

himself a great improver, as he was many other things at this period, wrote,

though with probable hyperbole, that there were 200,000 mendicants in the

Scotland of his day. It

hardly needs Ramsay's evidence to realise that want of money was the great

crux, a mortgage being almost the only expedient, and the Scotch laird must

have waxed pretty shy by that time of mortgages, lawyers, and their

intolerable prolixities. But he tells how money began to pour into Scotland

from outside sources after the middle of the century, and marvellously oiled

the wheels of agricultural progress. He has many good stories, too, about

the enthusiasm, and sometimes misdirected ventures of the "improving"

lairds, some of whom were enriched lawyers, making amends, as it were, to a

country on whose Poverty they had battened. As too self-confident persons

nowadays farming in a strange country proverbially fail to make allowance

for strange conditions, so many of these zealous Scotch lairds overlooked

the physical and climatic contrasts of Hertfordshire and the Lothians. But

with all these inevitable blunders they did magnificent work. English

ploughmen and bailiffs were imported, while the elementary but effective

treatment of liming the sour lands increased with leaps and bounds.

Enclosures, the use of clover and artificial grasses, draining, and finally

the introduction of turnips, all followed. The more intelligent tenants and

hinds, with the natural shrewdness of their race, which circumstances had

kept agriculturally dormant, conquered in time their aversion to novelties

and English importations and responded to the situation. "Often," says

Ramsay, "they became rather partners with their masters than mere payers of

rent, which was mainly in those days paid in kind." Many humorous situations

were created, which the laird of Ochtertyre, with all his powers of

practical observation, relates with relish. One " improving " laird,

hitherto such a book-worm that his health had suffered from confinement,

took the agricultural fever violently. Ike dropped his books, as well as all

intercourse with his neighbours, and took to the field himself in a fustian

frock, and even ate his meals under a dyke in company with his men. On

Sundays only he washed and dressed and became himself again. He imported

English labourers and all his implements, "and it was a sight," says Ramsay,

"to see wheeled waggons (for tumbrels with solid wheels had been the vogue)

with five or six sightly horses drawing his crops to market." "In spite of

many and inevitable blunders," says our author, "he became one of the most

spirited and skilful cultivators in the country. His management grew

judicious and his crops admirable." The end of the story is notorious,

though Ramsay scarcely lived to see its fruition. For in the nineteenth

century, the pupil passed the master, and the latter came eventually to sit

at his feet. A frequent aphorism of the Lothian farmer, which may be quoted

for what it is worth, attributes the comparative inferiority of English

farming to the lowness of rents, the stimulus to skill and energy being, in

his opinion, consequently lacking. It is at least interesting for one half

of the world to hear what the other half thinks about it. The laird in old

Scotland was probably, as a plainer-living and poorer man, more intimately

identified with the tillage of his land and with his tenants than his

southern equivalent. Just the very converse, as regards the Lowlands, has

undoubtedly been the case in the last hundred years. Ramsay tells a good

story of the tenant on an "old-fashioned estate," who always interceded for

the laird at grace before meat, but when

his rent was doubled immediately dropped that

clause in the peroration. If any southern reader of these pages should think

it worth while on the next opportunity to notice the plains of Lothian from

the northern mail; if any golfing pilgrim to North Berwick or Gullane should

peradventure devote that seventh day leisure, which the custom of the

country enforces on him, to a run through the neighbourhood, he will see a

sight as a whole nowhere else to be seen. When Mr. Balfour, while pleading

in a recent speech in the House of Commons for cautious legislative

interference with Lothian lands, alluded to them as displaying the finest

agriculture in the world, not one probably in fifty of his hearers

understood the significance of the truism the laird of Whittinghame was

uttering. It is a startling reflection that the grandfathers of the men who

created this country, much as we see it to-day, hitched wooden-toothed

harrows and primeval ploughs to their horses' tails, and ofttimes pulled

thistles from their lean grain crops to serve their half-starved animals in

lieu of green food. Long after the middle of the eighteenth century, writes

another authority, the whole of East Lothian was open field, much of the

land on rundale and divided among many tenants, who resided together in

clusters of mean huts called a town. Neither summer fallowing nor sown

grasses, nor turnips, were generally known. The labourers, says the same

writer, were shockingly housed, and more particularly on great estates, and

very liable to sickness, particularly ague. Oatmeal porridge had not, by

then at any rate, the hold it had acquired in some other parts of Scotland.

Pease bannocks, horribly unpalatable, though nutritious, were a staple diet

in the Lothians and Berwickshire, while barley scones were a luxury.

Potatoes proved an immense boon, being of fine quality, and associated as

they were with the improving diet which in other respects soon followed. |