|

THE alternative designations

of the county, which in this season of harvest now spreads before us its

undulating carpet of radiant patchwork between the broad, blue waters of the

Firth and the Iong swell of the Lammermoors, is a trifle bewildering to the

outsider. It makes for further haziness in regard to such of Scotland as is

neither within the orbit of the tourist nor the grouse moor market, and I

have, of course, only the benighted Southerner in mind. It is from no lack

of respect for his Northern neighbours that the average Englishman

cultivates this ingenuous innocence, geographical and etymological, for of

that I will venture to say the most prickly Scot could never complain. He is

quite catholic in these matters, and is almost as foggy, and quite as

content to remain so, regarding such parts of his own country as lie outside

his orbit. There is no reason to suppose that the well-to-do men and women

of Scotland are qualified to fling stones across the Border on this account.

"I am afraid very few of us know much of our own country" is a platitude of

which the present writer, for reasons not inscrutable, is the humble and

constant recipient, and there is nothing for it but an unreserved acceptance

of the obvious. There is a familiar, but happily now rare type of

politician, only known in Britain, whose motto is "every country but my

own." In the more venial sense of the phrase now under discussion,

irreproachably patriotic -persons by the thousand might. as justly be

branded with it.

The convertible terms of

Haddingtonshire and East Lothian are undeniably confusing to aliens in view

of this general fogginess. If the burning of a country house or an election

meeting from this quarter are reported in the London dailies, they will have

occurred in "Haddingtonshire." In the agricultural column on the next page

the root crops of "East Lothian" will be described as in a flourishing

condition. The writer of agricultural knowledge, that is to say, has an

unconscious respect for tradition. East Lothian will have a certain classic

ring in his ear, and if he has a sense of style as well, the cadence of the

term, as opposed to the preposterous ill-accentuated mouthful of the

alternative, would settle the question. The writer concerned with reporting

politics or thunderstorms or motor trials very wisely uses the hideous

official designation of Haddingtonshire, just as if it were any ordinary

county. I never heard a farmer in or out of it use any term but East

Lothian, and I fancy the folk of Linlithgow follow the same time-honoured

and admirable practice. Midlothian has no alternative, though on official

documents, I believe, the -County of Edinburgh" is the correct form. Even a

Saxon tongue, with its awkward and tiresome predilection for the first

syllable at the expense of the rest, would boggle at "Edinburghshire." Many

score southern golfers, of course, visit the classic links upon the East

Lothian coast; but very few of them, I imagine, know what county they are

in, and care less, which is characteristic. "Where am I?" said a gorgeous

but polite motorist to me one day upon the road just east of Cockburnspath.

He was entrenched within the body of a great and powerful car by stacks of

golf clubs, fishing rods, and gun cases. He had come from the far north and

was on his return south. In reply to my query he said he had a road map; but

it was nothing more. "Am I still in Scotland?" I told him he was still in

Scotland, and in East Lothian —a gratuitous crumb of information which did

not seem to convey anything definite—and furthermore, that he had the whole

county of Berwick yet to traverse.

"I thought Berwick was a

town; I had a half mind to try the Iinks there."

"That is North Berwick," I

replied, "and it lies over yonder behind you. But there's a town of Berwick,

and county too, which you will be in immediately."

He was very grateful for this

elementary piece of information, and asked me the best route to York,

concerning which I laid him under further obligations for half the distance.

"Now," he said, "I wish you

would let me tow you there." For I should have said that a bicycle was

Ieaning up against the wall, and I had been sitting on a gate looking at

some men beginning to lead a magnificent crop of barley, and wondering how

many quarters an acre it would run to.

I thanked him cordially, and

said I did not want to go to York, as I was, in fact, going out to lunch a

mile or two down the road.

He was very pressing,

however, that I should change my plans, and attach myself to the rear of his

forty horse-power car. He had carried a young man thus-wise, he said, at

thirty miles an hour the day before, for some prodigious distance, to his

infinite satisfaction, without a catastrophe. I retorted as nicely as I

could—for I have never met so grateful or so philanthropic a motorist in the

guise of a stranger on any highway—that I wasn't a young roan, and did not

in the least want to go to York or even Newcastle, and most certainly not at

thirty miles an hour—above all, on a bicycle of nameless brand that I had

hired for the day in Dunbar. This last pretext seemed to have some sense in

it, and we parted friends. I took the opportunity of advising him, however,

to refrain from attaching even the young and the reckless to his car over

the North road beyond the Tweed. For every hundred yards or so, upon the

Northumbrian section of that famous highway there is, without fail, a large

fragment of loose whinstone, more or less in the middle. What would happen

to the man in tow when he blindly struck the first of these may be left to

the imagination.

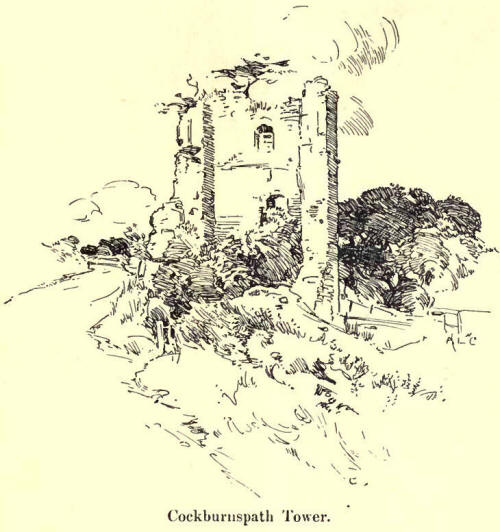

About a couple of miles from

Cockburnspath, a sequestered village, lying amid the bare cultivated

foothills of the Lammermoors and just in East Lothian, is occasionally

visited by antiquarian societies. This is Oldhamstocks, a typically Saxon

name in this very Saxon country, Auld-ham being obvious, and Stoc, I

believe, also indicating a place or home. The point of interest is a little

thirteenth-century chancel, long disused but structurally intact, and in

strange conjunction with an uncompromising type of the eighteenth-century

Scotch kirk. The scarcity of pre-Reformation survivals gives local interest

to fragments that in the happier hunting-grounds of the south would attract

slight notice. But the mere fact of such rarity, and the mere distinction of

having survived the far more relentless forces of destruction, English and

Scottish, that operated here, lends a certain pathetic interest to a monkish

ivy-covered chancel, leaning up against a friendly, tolerant, but frankly

hideous design of the bald days of Presbyterianism. As a matter of fact, the

little chancel, with its decorated window tracery still complete, had some

further interest in not being monkish in so far that the church and advowson

never was the property of a monastery, but appertained for all traceable

times to the Lord of the Manor or Barony. Oldham- stocks, too, infringes the

usual Saxon custom just alluded to, in that the accent is here thrown on the

penultimate.

I journeyed out one day to

this village, which is a marked exception to the usual East Lothian type.

For it lies aloof from the world, and between high hills which tillage has

furrowed nearly to their summits, leaving green rounded crests of sheep

pasture. The village itself stands picturesquely along a green, with the

church and manse at one end of it in southern fashion, and looks like a

place that has nourished hardy hinds and stout prejudices. I wasn't thinking

of that, however, when I left the churchyard to retrace my steps and fell

into company on the highway with a man who was certainly the former and

deeply imbued with the latter. He was advanced in years and rather low in

stature, but bore upon one shoulder with apparent indifference a log of

portentous dimensions. On my remark that it looked like a wet night, with

some further commonplace regarding the old part of the church, the following

dialogue ensued

"Aye, it's a thousan' year

auld they say; just yin o' that auld monkish buildings."

"It is between six and seven

hundred years old," I replied.

"Deed, then, an' how do ye

ken that?"

"I can tell it for a

certainty by the window for one by thing."

"Ye can ken how mony hun'erd

year old it is by looking at the windy? Mon, that's wonderfu'. I've heard

tell there's the marks of anither auld buildin' on the top o' yon brae."

"What sort of building was

it?"

"Oh, jist some o' thae auld

papish nonsense; and as to that, I'm thinkin' we'll a' be Romans agin sune."

For the moment it only

crossed my mind that some vague echoes of advancing ritualistic practices

across the Border might have reached Oldhamstocks through the weekly paper.

"Well, you're safe enough in

old Scotland at any rate."

"Safe in auld Scotland!" the

little man shouted with a voice quivering either with excitement or the

weight of the weaver's beam, to use a metaphor appropriate to the occasion,

under which he was labouring. "Safe in auld Scotland! Auld Scotland's

ganging to Rome jist as fast as any of 'em."

"At least," I said, "there's

nothing of that up here in Oldhamstocks."

"Naethin' o' that up here!

Lord save us, we're jes fu' o't every Sabbath."

This was getting a little

uncanny, for there was no stained glass window in Oldhamstocks kirk, nor, I

think, had it been reseated in the Anglican fashion, and the pulpit shifted,

as has been done in some country churches; while the edifice itself was

absolutely above reproach from this staunch Covenanter's point of view.

"What is the name of the

minister?" I asked.

'He's a mon they ca-----'

Now, in the south this would

merely indicate that the parson was a stranger recently inducted, and that

the spokesman took his name on hearsay, as having somewhat less than no

interest in the newcomer. But this frequent idiom of the common folk in

Scotland, "they ea' him," in answer to such a query as the above one of

mine, and in reference to a man they have perhaps known all their lives, has

surely an element of humour in it. It would be straining a point perhaps to

say that it was the proverbial reluctance of the Scot to commit himself

definitely, and that without the knowledge of a man's genealogy there could

be no positive certainty there had not been some remote hanky-panky with his

patronymic. The respected, and, I believe, entirely orthodox divine in

question had, it transpired, been thirty or forty years in charge. To cut

our discussion short—which is more than my log-bearing friend did, for he

kept it up all through the village, and for some distance beyond, as our

respective ways coincided—it seems that he scented some taint of

"justification by works" in the parish pulpit—an appalling doctrine to his

thinking. how this amiable tolerance savoured of the scarlet woman, I cannot

imagine. But then I am not equipped to fathom the controversial depths of

the old-fashioned Scottish theologian. One may appreciate the piquancy he

has (riven to Scottish history, and feel that he has, at any rate, made

nearly two centuries of what otherwise a Scotsman will admit with certain

notable exceptions to be a rather wearisomely turbulent chronicle, a very

interesting one. All this may be gratefully realised without being competent

to enter the lists with a village Cameronian, even though weighted down by

half a tree. however, my Covenanter was not so dour as might be gathered

from this brief narration. For he laughed quite immoderately at some

trifling passage we had, as our ways diverged, and we parted friends, though

I suspect he took me for a "Roman."

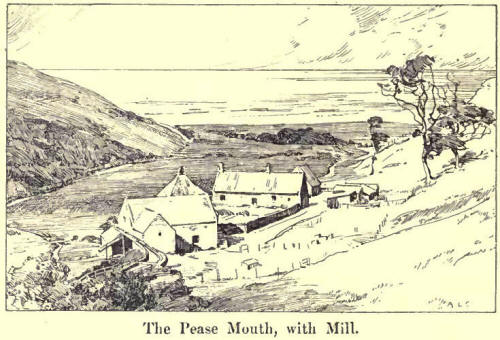

The rolling plain of East

Lothian begins at Pease Pass and Cockburnspath in a narrow strip between the

sea and the hills, and gradually expands in fanlike shape as you travel

westward in the direction of Edinburgh. This is a country with a character

entirely of its own. It is unlike any other in Scotland, and still more

unlike, it would be superfluous to add, any region of England. It might be

likened to a vast garden lying between a rocky, broken coastline and a wild

waste of moor. Not a garden country in the sense of Kent or the Isle of

Wight, to quote familiar illustrations of a hackneyed term; nothing in

atmosphere, traditions, or surface, could be more utterly different. 'There

are no lush hedgerows, no flowery lanes, no

picturesque, unkempt

orchards, no crooked lines. It is a garden of twenty- or thirty=acre fields

geometrically laid out and divided by well-built stone walls or low clipped

thorn fences, upon either side of which no foot of space is given to the

unprofitable or the picturesque in nature. Turnips, barley, seeds, oats,

potatoes, wheat, as the old rhythmical mernoria technica of the East Lothian

six-course shift had it, may be roughly taken as indicating the composition

of the rich-coloured patchwork that lays along the levels and climbs the low

hills.

At intervals stand the great

farm steadings, bearing to one another a certain family likeness not common

in the south, and giving an appearance of formality which is strengthened by

the tall unlovely chimneys of the stationary engines, though somewhat

ameliorated on the other hand by the warm red sandstone walls and red-tiled

roofs of the out-buildings and cottages. Here and there—and this bird's-eye

view of the country comes natural, for the sufficient reason that you can

see nearly all over it from almost any slight elevation—are the great

country seats, which are on a scale proportionate to the high-rented,

scientifically-cultivated farms belonging to them, entrenched within

luxuriant woodlands and green parks that are virtually the only permanent

grass in the country. The Merse is a fat and opulent region; but this is a

step higher, and cast, moreover, in a different setting. What sort of appeal

it would make to a stranger turned suddenly loose into it, and conducted at

a leisurely pace from Cockburnspath to Dunbar, and on to Haddington or North

Berwick, it would be difficult to say. He would be a cockney indeed,

however, who did not recognise the fact that he was looking over a type of

rural landscape, the like of which he had assuredly never seen before. A

farmer from Norfolk, Lincolnshire, or the best of Yorkshire, would become

conscious at once that his standards of excellence were shattered and

required readjustment.

The shock of surprise, for

the term is no whit too strong, would be modified something, to be sure, by

an approach through the Merse, but there is no reason to consider unlikely

suppositions. It has been my occasional lot to be in the company of visitors

of this type, undergoing this altogether new experience, and still oftener

to hear it recalled by such in distant counties as the experience of their

lives. The farmer of Norfolk or Lincolnshire, who, speaking broadly,

represented the most enlightened type of English agriculturist when skill

and capital worked in fearless and secure combination, occasionally visited

this country. But the Norfolk or Lincolnshire farmer threw up the sponge at

once at the very first glance at East Lothian, and frankly recognised that a

gap divided it from the best that he could show or had ever seen. The simple

fact that men of skill, substance, and capital were paying four and five

pounds an acre rent, while he was paying two and three for the best land,

with about the same profits in either case, would alone have given the crack

farmer from the south something to think about. Yet in the eighteenth

century the Lothian lairds were importing English bailiffs, under no little

opposition, to show their reluctant and comparatively backward tenantry how

to farm! As already remarked, a professional equipment is quite unnecessary

for a general appreciation of these conditions. A layman with eyes in his

head and an ordinary acquaintance with country life would recognise at once

an unwonted spectacle, and would surely be compelled to some measure of

admiration. For if the breed who made the country have mostly left the soil,

and their places know them no more, their successors nobly cherish their

great traditions. The economic world has been turned upside down since their

day. The financial readjustment which enables the man of the present to

withstand the altered conditions does not for the moment concern us. It is

enough that East Lothian displays the same wonderful face as of old. The

superficial changes are insignificant. Even the drop in these high rents is

as nothing to the slump that has overtaken the far lower ones in some of the

crack counties of England.

The normal reader will have

probably made up his mind by this time that East Lothian, for the normal

visitor, must be an intolerably dull county; and in a nation such as we are

now, it would be futile to expect many people to find compensation in the

highest triumphs of agriculture, or to appreciate the unique exhibition of

them that are here displayed. But as a matter of fact, this perfection of

neatness and abundance doesn't altogether make for the monotony which would

he inevitable in many countries. The layman, oblivious to all these things,

could not forbear, if he had a soul within him, from recognising a country

that in other ways, too, was of an uncommon quality. Stand almost where you

will, the eye ranges far away over the rich clean patchwork of the plains,

with their intervals of stately woodland, to blue stretches of sea, bounded

by long billowy coastlines, rising at times almost to the height of

mountains. And again, if the formal opulence of the foregrounds offend an

aesthetic sense not capable —speaking without offence—of feeling their

significance, the continuous presence of the unbroken wall of lonely

moorland, that for the entire length of the county upon the inland side

waves along the near skyline, from its very contrast must make a further

appeal.

Once over the deep woody

deans of Cockburnspath, everything that is wild, bosky, or rugged in nature

forges away with the Lammermoors, and you are at once into the narrow

eastern wedge of East Lothian, which widens gradually as you approach

Dunbar. This is the cream of the country—probably the cream of the earth.

For some fifteen miles approximately, extending lengthwise to the course of

the Tyne, and in width from the edge of the red cliffs or sandy dunes which

succeed them, to the foothills of the Lammermoors, lie the famous "Dunbar

red lands." Brilliant to the eye in hue, and brilliant in the rich colouring

of the crops they carry, these red barns are supposed to combine a maximum

of fertility with friable, easy-working qualities in greater perfection than

any other soil in Great Britain. Upon the top of this, they have been

subjected to the lavish and liberal treatment of the Lothian tradition,

which was not due to natural advantages, but has handled this whole country,

whatever its varying soil qualities, which are many, with the same skill.

But the red land country of Dunbar, associated for obvious geographical

reasons with that ancient town, is from an agricultural point of view the

most interesting portion of the county. I think it is otherwise the most

picturesque. For the colouring of itself is so rich, the woodlands of

country seats so abundant, the sea so near upon the one hand, the rising

ridges of the Lammermoors foothills so reasonably close upon the other.

In matters material the

potato is here king. That invaluable but prosaic root suggests to most of us

a host of little market gardeners covering the countryside with mean

dwellings and makeshift out-buildings. The potato of the Dunbar country is a

magnificent creature of quite aristocratic associations, and is something of

a gamble to big farmers, just as hops are to the farmers of Kent. It doesn't

condescend to the two- or three-acre strips or patches with which it is

hopelessly associated in the popular eye. It follows oats (generally) in the

ordinary farming shift, and, stimulated by powerful doses of fertiliser,

barn-yard and artificial, spreads a level sea of lusty shaws and flowery

tops in summer-time from fence to fence, to make way in autumn for a crop of

wheat that I have known myself go to eight quarters an acre. And a crop like

that was worth something in Haddington when the price was from fifty to

sixty shillings a quarter! Even at the present miserable prices, the normal

expectation of six quarters which East Lothian looks for in a fair year must

leave a margin.

Just after the beautifully

clean stubbles had been cleared of their crop in this particular year, I

took the trouble to count the freshly-erected grain stacks in three

consecutive homesteads, all within easy sight, near the road between Dunbar

and Cockburnspath. In one there were just a hundred, and in the two others

between sixty and seventy apiece. The swedes and turnips, which as of old,

in the six-course system, generally follow wheat, are a goodly sight, clean

as a garden, and the roots, when matured, seeming at times almost to jostle

one another out of the drills. This is a dry climate, in spite of the hills

and mountains that are visible near and far from these Lothian fields. To an

eye accustomed to noting the crops in many counties year after year, it

seemed strange to find in mid-July the farmers of the Merse and Lothian

crying for rain after weeks of drought, yet their swedes and earlier-sown

turnips flickering strong and lusty in the wind over the large fields, and

much fitter, indeed, to hold birds than many a southern root field in early

September. No waste ground is here—neither open ditches, nor rambling

fences, nor tousely corners, nor ragged headlands, and, generally speaking,

no hedgerow timber to draw the land and obstruct the sunshine. The crop

pushes stiff and level up to the stone wall or trim thorn fence, which in

the growing and maturing season subside into thin faint lines hardly

discernible amid the lush abundance. But potatoes throughout East Lothian,

and above all in these Dunbar red lands, as already related, were and are

the most attractive crop to the farmer. Other products have their limitation

in market price, being forced to compete with the cheaply grown stuff from

the virgin soils of three other continents. It may be worth reminding some

readers, too, that the good average and profitable yield of a Manitoba farm

would be accounted a dead failure in East Lothian, and scarcely profitable

in Wiltshire or Suffolk, while the average yield per acre in Australia or

the United States would be ploughed under ruthlessly either in England or

Scotland.

But potatoes cannot he

carried about the world so readily, nor grown wholesale with a trifling

expenditure of labour. For they need a great deal, and it might be set down

as against the Lothian and Berwickshire farmer that the price of labour has

gone up enormously since the last generation tilled these generous

fields—that of men about 40 per cent., and of women twice as much. Forty

years ago, too, the "Dunbar regent," the favourite of that day, held the

London eating-houses and supper-rooms in the hollow of its hand, and fetched

double, or nearly double, the price of any other late potatoes grown in

Great Britain. There are still none in the market comparable to the delicate

mealy product of this red loam belt of East Lothian. But the old exclusive

prices and the particular demand which created them have passed away, and it

only tops the market by some 10 or 15 per cent. But the average under

potatoes is fully as large as ever, while wheat has given way greatly to

oats and barley. The profits in a good year, unlike grain, still mean money

in the cornmercial, not the agricultural sense of the word. Potatoes are, of

course, something of a gamble, for potential disease always hovers over the

crop like a destroying angel. When dreary wet days follow one another in

August, the ominous, pungent odour as surely begins to scent the air,

telling of mischief that will spread apace if the elements remain perverse,

and of thousands of pounds sinking surely into the soil, which has been

manured and fertilised with a lavishness that would make a Devonshire farmer

gape with amazement. I mention the Devonshire farmer, not because he also

ploughs the red sandstone, on the little fields wedged in between his

portentous bank fences, but because—what no one would be altogether

surprised at who knew the county—he foots the list of English shires in the

official returns of grain per acre.

The old farming families have

for the most part left East Lothian. They have not, dear readers, gone to

Canada, though I have no doubt the labourers have done their share in

swelling the prodigious army of fit and unfit that have crowded the Atlantic

steamers for the last dozen years. The East Lothian farmer years was not the

type of person who would look upon a half-section in the north-west, and a

"shack" or even a four-roomed frame house, combined with twelve or fourteen

hours a day manual labour, as a fine opening. He was a gentleman who dealt,

as his successors doubtless do, in thousands—to his profit in former days,

if to his loss in the 'eighties and early 'nineties. He frequently paid a

rent of £2000 a year. He did not, as his successors doubtless do not, enter

upon a farm, and would not have been accepted in the competition of those

days, without a capital of many thousand pounds. He often put two or three

sons into farms requiring five or six thousand pounds (£12 an acre was about

the minimum estimate) for the stocking thereof. There was a great debacle

amongst this admirable race of men in the 'eighties and earlier 'nineties,

the stock whose forbears had made this country a world's spectacle—the

agricultural world, that is—and who in their own persons were farming

nobly., The long leases at high rents hitherto equitable, caught many in the

great slump. Nobody foresaw it, though they ought to have. Neither

landlords, lawyers, agents, nor farmers in Scotland or in England could see

the writing on the wall that was plain almost to a schoolboy who knew North

America—the first and most powerful source of attack in the 'seventies. That

British land would be worth so much an acre till kingdom come, was almost a

religion among the shrewdest men in both kingdoms. The present generation,

whom a bitter experience has utterly divorced from the creed of their

fathers, cannot imagine the pride and confidence in British real estate that

was ingrained in the very blood. The shrewdest lawyers bought land, or

invested their clients' money in it, with infinitely more confidence than

they would buy Consols to-day, which is not, perhaps, saying very much. Here

is a trifling but pertinent incident: its unavoidable egotism I may be

forgiven. I was paying a flying visit towards the end of the 'seventies to

an old friend, son of a famous farming family, then sitting himself on a

superb farm of Dunbar red land at five pounds an acre. I was then farming

myself in one of the old states of America, where the spectre of the

rapidly-opening West, and its virgin grainfields, was already beginning to

flap its wings, and to depreciate land, and to depress the rural communities

with the certain promise of worse things to come. The agricultural situation

of the two countries, the old long-established regions of the United States,

and of Canada too for that matter, on one side of the ocean, and Great

Britain on the other, was practically identical. Their farmers, too, had had

their day, and being always owners, their pride of land, so far as the sense

of its security, is implied. But the first whiff of the impending storm,

from which they have never to this day recovered, had already begun to

ruffle the calm of the yeomen landowners from Maine to Maryland, and to

depress the incipient, but sanguine efforts to restore the fertility of the

worn-out plantations of the slave states. It was only a question of more

railroads and more steamers, which were both making ready response to the

awakening of the Virgin West. Any one nearer to the quarter whence the storm

was coming could see it—man, woman, or child. Indeed they were feeling it.

The agriculturist sowing grain on his well-equipped farm in New York or

Pennsylvania worth £30 an acre, as sound value hitherto as a staple

investment, and as profitable to work as a farm in Essex, had already cause

to be anxious. But Great Britain, despite the warnings of occasional

newspaper correspondents, seemed absolutely unconscious of any impending

calamity. People were bewailing one or two ruinously inclement seasons, as

if that were all! On the occasion the memory of which has provoked the

parenthesis, I ventured prophetic utterance merely to what was obvious to

any one then living within the mutterings of the brewing storm. My friend is

now kind enough to say that it stuck in his mind, and was recalled when the

crash came. At the time, I think, he relit his pipe and smiled grimly across

the hearth. Seven or eight years later, farms known to me in Essex and

Lincolnshire with a former rental of 30s. to £2 an acre, were selling or

being vainly offered at £10 to £15 an acre in fee simple, and hundreds

throughout England were derelict.

It is needless to recall that

in spite of slow and partial recovery, and in places through changed

conditions, complete recuperation, the blow was final. For better or for

worse, that is to say, rural England and Scotland have never been what they

were before. That chapter, with its pride, its security, its traditions, one

might almost say its arrogance, was definitely closed. This is, of course, a

mere truism. But it is pleasant to remember those old days all the same.

There was a something not easy to describe in country life that has never

returned. It crumbled away in the 'eighties; and what must have struck, and

did strike many at the time, was the difficulty with which a kind of

superstition that land must represent so much an acre died even in the face

of facts. This was obviously due to the long divorcement of landlords, in

Great Britain more than in almost any other country, from a sensitive

partnership in the soil, and a practical knowledge of and interest in

agriculture. Large estates and a capitalist tenantry had everywhere relieved

them from such practical intimacy with their own acres. After all, a love of

country life as represented largely by sport, has little really to do with

practical agriculture, though it is often conventionally associated with it.

To landlords, agents, and solicitors, land had been so long merely

represented by a money rent, and the fee simple value at so many years'

purchase of the same, that the original partnership idea had been lost sight

of. The revolution was too sudden for breaking an ingrained attitude. It was

not only that they did not foresee it, which they ought to have done : but

after it had come they were even still inclined to discuss rental figures as

based on old practice, instead of facing the fact of the world's movements

and markets. It is perhaps not surprising that a decade was hardly

sufficient to break an immemorial belief that the soil of Great Britain was

almost sacred, and that a temporary 10 per cent, reduction was sufficient to

stem a cataclysm.

The splendid condition of

Lothian agriculture, its long leases and high rents, cut both ways. Whatever

befell the sitting tenants, the old farming families, the capitalists of

those days, there were sanguine people ready to take their places at rents

not seriously reduced, on farms so well equipped and in such beautiful

condition. No derelict farms ever marred the landscape of East Lothian. On

the contrary, whatever hearts or pockets were breaking, the country kept a

smiling face. It is no place here, even were I competent to do so, to touch

upon the tale of loss and trouble that must for years have depressed the

farmhouses of East Lothian. That most of these old families vanished in the

process need not of necessity indicate financial ruin. Their sons were

well-educated, practical men. Farming had been a pleasant and reasonably

profitable business at 8 or 10 per cent. The big farmer was a man widely

envied in those days. There was even something of a social glamour about it.

But it became a very different matter when the woes of the farmer and the

landowner became a chronic national refrain, and the position dropped from

one of profitable and otherwise enviable ease to an anxious struggle to make

both ends meet. It would have been strange indeed if the young men who saw

this struggle at close quarters elected, with the world before them, to

continue in so unpromising a career, and it is not surprising that commerce

and the professions drew away from East Lothian and its neighbours—but I

think particularly from East Lothian—most of the names with which its rise

to fame is associated.

These are days of totally

different standards, days of readjustment, and incidentally, too, of

faddists innumerable—days too, let us hope, of more cheering prospects,

though the proud old times of agriculture and of landowning too, as such,

have utterly vanished. East Lothian, save for this departed glamour, goes on

almost precisely as of yore. The rents are now only down about 15 per cent.

The rents of some arable counties are down from 50 to 200 per cent.

Away from the hills East

Lothian had, in my youth, not a single field but the laird's parks in

permanent pasture. At least so it was said, and I certainly never saw one.

It has even now so little meadow as to be unworthy of notice. It is still,

as I have said, beautifully farmed, and presents a perfect picture. Though

showing considerable variety of soil, nature has intended it for an arable

country, just as she has intended others to be mainly grazing countries, not

because they are poor, but because they are richer in the value of their

beef and mutton than they ever could be in grain. In former days there was

tremendous competition for East Lothian farms. Speaking generally, there was

no sentiment attaching to the particular homesteads as in most parts of

England then. The farming families took a commercial view of the situation,

and put their capital, when a lease was up, wherever the best opportunity

offered, and not infrequently into more than one farm. The mutual attitude

of landlord and tenant, again, struck a southerner in those days as almost

wholly lacking in what might be called the quasi-feudal flavour, traditional

in England, and, no doubt, in some other parts of Scotland. The tie was of a

merely commercial nature—a nineteen-year hard-and-fast lease, and there was

an end of it. The Lothian landlords may well have been proud of their

tenantry. But the mutual feeling, though generally friendly, was not in the

least feudal, to use a convenient term, and in no sense intimate. I don't

think home farms had any appreciable existence. At any rate, one never heard

of them as counting for anything. It would have needed an exceptional

indifference to income to play with three hundred acres, which would

otherwise represent a clear thousand and odd pounds; while the notion of

setting a good example, admirable perhaps in more backward countries, would

have been, of course, ridiculous in East Lothian.

I remember very well, and for

excellent reasons, an incident which made a great stir at the time

throughout Great Britain: but I find it quite forgotten, even in the

locality, or rather that there is scarcely any one left to remember it. Long

protracted tenure and its consequent local attachments were not entirely

wanting, though, as I have ventured to indicate, they were not

characteristic of the county in the 'seventies. But a distinguished farmer

in a case where these conditions did happen to exist in a very marked degree

was given notice to quit at the end of his lease for political reasons.

There was a tremendous row, not in any way promoted by the party most

concerned, who was of a proud and quiet disposition. But the press of the

United Kingdom, not then prone to sensationalism, took it up, and even that

of the Continent, whose agriculturists in those days, regarding Great

Britain as their model, and East Lothian as its apotheosis, echoed the

controversy.

The offending landlord was a

Tory with stout convictions of a kind not uncommon then, but which would

make the hair of the staunchest Conservative of to-day stand on end. The

tenant was a Liberal of the mild kind which then answered to the term, but

who, if he were alive to-day, would almost certainly be of the other faith.

His particular offence lay in having contested, though unsuccessfully, a

Scottish constituency. Even foreigners wrote indignant letters to the

British Press to the effect that Mr. A., the aggrieved party, and his farm

had a European reputation, whereas they had never even so much as heard of

Mr. B., his landlord. This was natural enough, though not quite to the

point, nor precisely in perspective, as the gentleman in question, an

otherwise just and upright man, had actually held office in a former

Government. However, it was a nine days' wonder, and stirred political

passions no little for the moment. Agricultural politics in those days

hinged mainly upon the law of hypothee and the extreme preservation of

hares. The former, abrogated in due course, gave the landlord certain

preferential rights over all other creditors, which were considered harsh

and otherwise disadvantageous to the tenant. The latter was really a great

scandal. The fields in some parts were literally covered with half-tame

hares. To say that on a fine autumn day

you could count thirty and

forty squatting about a clean stubble field of less than that number of

acres is the mere literal truth. The damage such a number did to the noble

fields of turnips by nibbling at the tubers and setting up decay, seemed in

common sense out of all proportion to the sorry sport afforded by a

multiplicity of ground game. East Lothian, like much of Scotland, was and is

a fine partridge country, but nothing can make a hare in a serious and

wholesale sense an exhilarating mark for the gun; while of all a gun's

victims poor puss suffers most from the tinker and the tailor, the

long-range blazer and the schoolboy.

A keeper in Shropshire I was

constantly out with many years ago, an admirable type of his class, served

his early terms on a famous shooting estate in Norfolk. He has often told me

that if the list of hares slain on a big day did not reach four figures,

there was a rating in store for the keepers. The modern shooting man, if he

does not live laborious days, is critical as to the class of shot offered

him, and may well wonder what his predecessors could have seen in this sort

of fun—at the cost, too, of so much justifiable ill-feeling. But it brought

on the Hares and Rabbits Bill, which has so thinned the former, save on the

Wiltshire Downs and a few other spots, that there are not much more than

enough of them for coursing and hunting, the proper metier, perhaps, of this

graceful, fleet, and timorous beast. But mingling in rather odd contrast

with the confiding game, both fur and feather, that swarmed on these fat

Lothian fields in autumn and winter, came the constant rush of the wilder

denizens of the air—the freer spirits from the moorland and the sea. Great

flocks of wild geese spent, and I believe still spend, every day for months

upon the young wheat or seeds, particularly appreciating the leavings of the

lifting ploughs on the cleared or re-sown potato-fields. Honking inland in

the morning and back again to the seashore at sunset, a big flock of wild

geese would be almost as continuously in evidence as the partridges or

hares, or the clouds of pigeons which, pouring out of the various "doo'cots"

in the neighbourhood, were another characteristic feature of the East

Lothian landscape. There, however, the similarity ended. For the genius with

which a hundred or so wild geese mingled daily in the bustling life of a

great farm, and yet kept themselves practically unapproachable by the most

crafty sportsman, was amazing. Golden plovers, too, seemed always on the

wing at dusk in these darker months with their plaintive whistle, while

there were more wood-pigeons in East Lothian in those days than in any

country I have ever seen, which is saying a good deal. |